Uncovering JAPA

Simplifying Coastal Planning for Small Cities

Uncertainty is the watchword of climate planning, but to plan for uncertainty a government must have the institutional capacity and the political will to model various scenarios and policies.

Many coastal municipalities simply do not have the resources to examine the potential effects of climate change on their communities.

What is needed, particularly in small cities, is an adaptable toolkit that offers policymakers a lens by which to understand the complex relationship between coastal changes and local regulations.

Scenario-based Coastal Planning for Municipalities

"Using Simple, Decision-Centered, Scenario-Based Planning to Improve Local Coastal Management" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 85, No. 4) describes the development and testing of one such model, using off-the-shelf data sources and easily categorized scenarios to offer officials from small, coastal cities along Lake Michigan an array of possible futures and policy choices.

Authors Richard K. Norton, Stephen Buckman, Guy A. Meadows, and Zachary Rable first worked with two municipalities to develop their planning assessments. Then they tested them with two other municipalities — Grand Haven City and Grand Haven Township in Michigan — in the process of updating their coastal master plans.

The authors used Participatory Action Research to develop and deploy their models and scenarios. Once Grand Haven City and Grand Haven Township had completed their plans, the authors compared 20 master plans from municipalities within the planning district to the plans developed by the four partner cities.

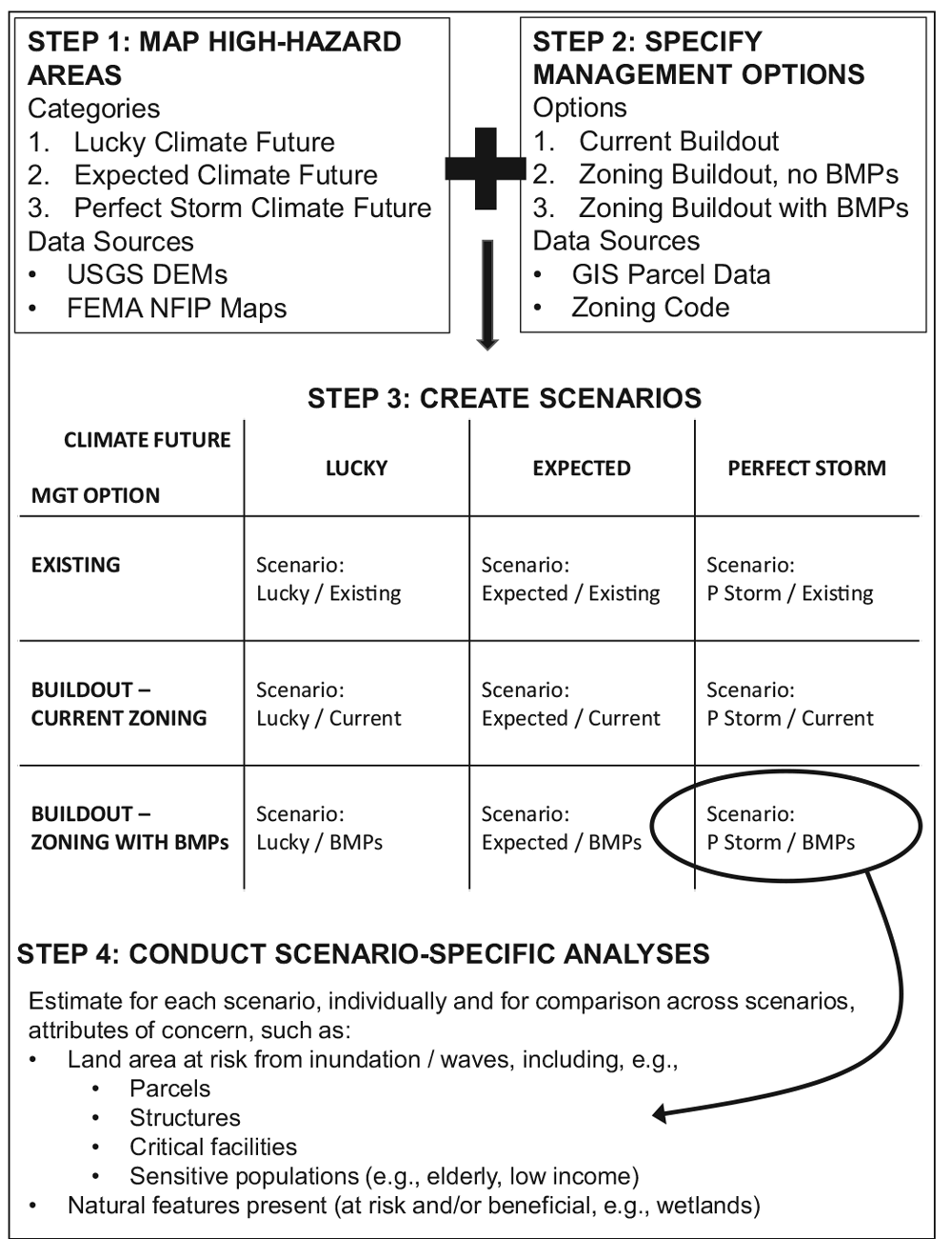

Diagram illustrating the process for developing and analyzing scenarios. From "Using Simple, Decision-Centered, Scenario-Based Planning to Improve Local Coastal Management," JAPA (Vol. 85, No. 4).

Enhancing Coastal Planning With Scenarios

Norton and his co-authors offered officials from Grand Haven City and Grand Haven Township "three potential 'climate futures' that might yield hazard conditions outside the control of the locality." These futures, termed lucky, expected, and perfect storm, combined two measures: standing water levels (sea level rise) and increasing storminess.

They then offered a straightforward set of policy choices for shoreland management and hazard mitigation and modeled the consequences of those choices against the three potential futures.

Ultimately, the authors find that "a simplified, decision-centered" approach to scenario-based planning has the potential to improve the outcomes of shoreline master planning processes, particularly in small municipalities.

Officials debated and doubted the implications of the scenarios, but eventually both communities included complete versions of the processes' findings somewhere in their master plans (one in the body of the report, and one in the appendices).

The results are encouraging, especially considering places where the political contexts appear less amenable to land use planning that takes hazard mitigation into account. Similar simplified processes could be adapted straightforwardly to other settings, including ocean coastal cities, the authors suggest.

However, given the challenge of adapting to climate change across multiple scales, it is not clear whether, in the mid-to-long term, small municipalities should maintain home rule over coastal land management. In the U.S., states may prove the more coherent scale by which to study and distribute resources and risk.

However, this is not a criticism of the article, which highlights a small but important step in the process of developing tailoring hazard mitigation planning for coastal contexts of all kinds. Cities everywhere face the challenging triad of large mandates, diminished resources, and uncertain futures.

By simplifying scenarios and using intelligible processes, it is possible that experts could offer small cities access to an essential but highly complex and politically fraught area of planning.

Top image: Icy Lake Michigan coastline at Grand Haven, Michigan. Photo by R. Greaves, NOAA Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory (CC BY-SA 2.0).