Uncovering JAPA

When Climate Resiliency Is More Than an Afterthought

The effect of disaster is not experienced equally across communities. Research continues to demonstrate that wealthier households are more equipped to rebuild and relocate. But where does this leave low-income households?

The ideal solution is to ensure that low-income communities are best protected from disasters before they occur. And when this is not possible, they have how to recover quickly.

"Affordable Housing, Disasters, and Social Equity" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 86, No. 1) explores how the federal government may support disaster-resilient communities, particularly through Low-Income Housing Tax Credits.

Housing Policies and Disaster Preparedness

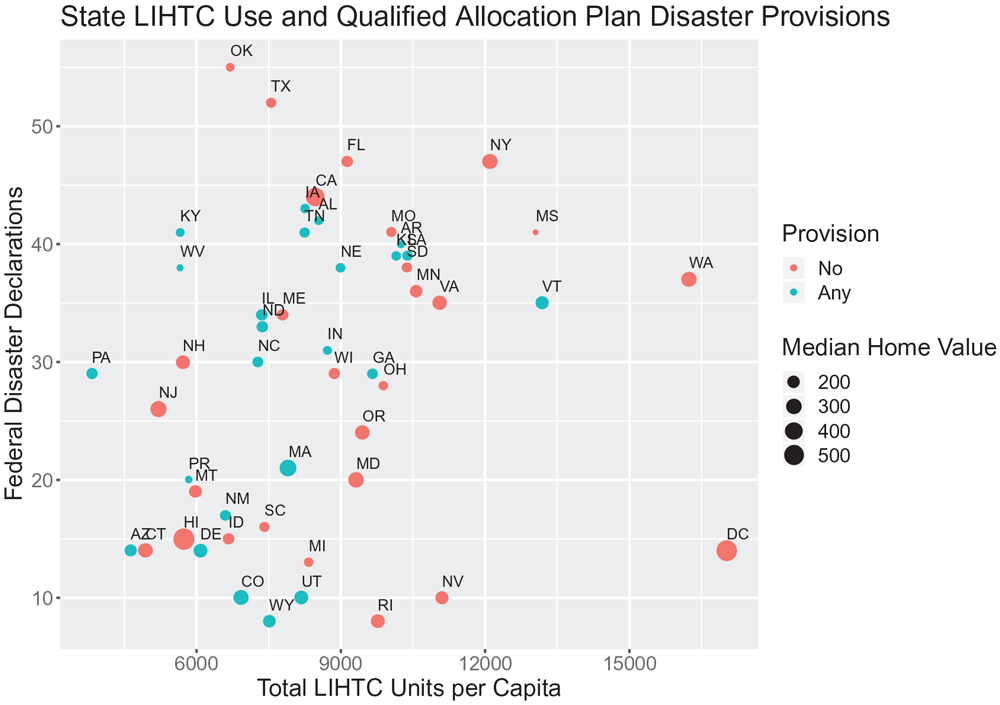

Authors Aditi Mehta, Mark Brennan, and Justin Steil analyze qualified allocation plans (QAPs) for 53 states and territories searching for provisions related to disaster preparedness and recovery.

They find that 24 governments include such provisions — with 13 incorporating preparedness, three recovery, and eight both. Preparedness provisions focus on the design and location of developments, such as located within a floodplain or equipped with storm shelters. Recovery provisions, by contrast, seek to direct funds to areas that have been affected by disaster by, for example, supplying additional funds or rebuilding lost housing units.

This leaves 29 states and territories with no such provisions. However, among them, the authors find common characteristics.

States with higher rates of homeownership, lower home values, and lower rents are more likely to have one or both types of provisions. This means states with high renter populations and high housing costs — states most vulnerable to economic stressors — are most vulnerable to disasters.

Figure 1: Understanding differences in LIHTC allocations and QAP provisions.

Resilient Housing Strategies for Disasters

Moreover, the authors find that the number of federally recognized disasters experienced by a state does not predict whether resiliency provisions are a part of its QAP. This is evident through states such as Texas and Florida which, despite being known for their exposure to hurricanes, have mandated no protections for their LIHTC developments.

For the authors, a congressional mandate requiring states and territories to include resiliency criteria in LIHTC QAPs is an important step to mitigate the impact of future disasters. To bolster this, states might also reassess how LIHTC units are leased up.

Including households affected by disasters among preferred residents, just as is done with low-income, family, or older adult households, may support households recovering from disasters. Ultimately, the nation's greatest resource for affordable housing creation may represent its greatest protection from disaster for low-income households.

Top image: Destruction from Hurricane Michael near Panama City, Florida, in 2018. Photo by Flickr user U.S. Customs and Border Protection (United States government work).