Uncovering JAPA

Gender Equity and Shanghai's Shared Rental Market

Is society neutral? While many of us may wish it was, it is undeniably not. Whether it be on racial, gender, religious, or socioeconomic grounds, society neither treats, expects, nor demands the same of everyone. Compounding this is that in a dynamic society with shifting circumstances and environments, there are ever-emerging inequities.

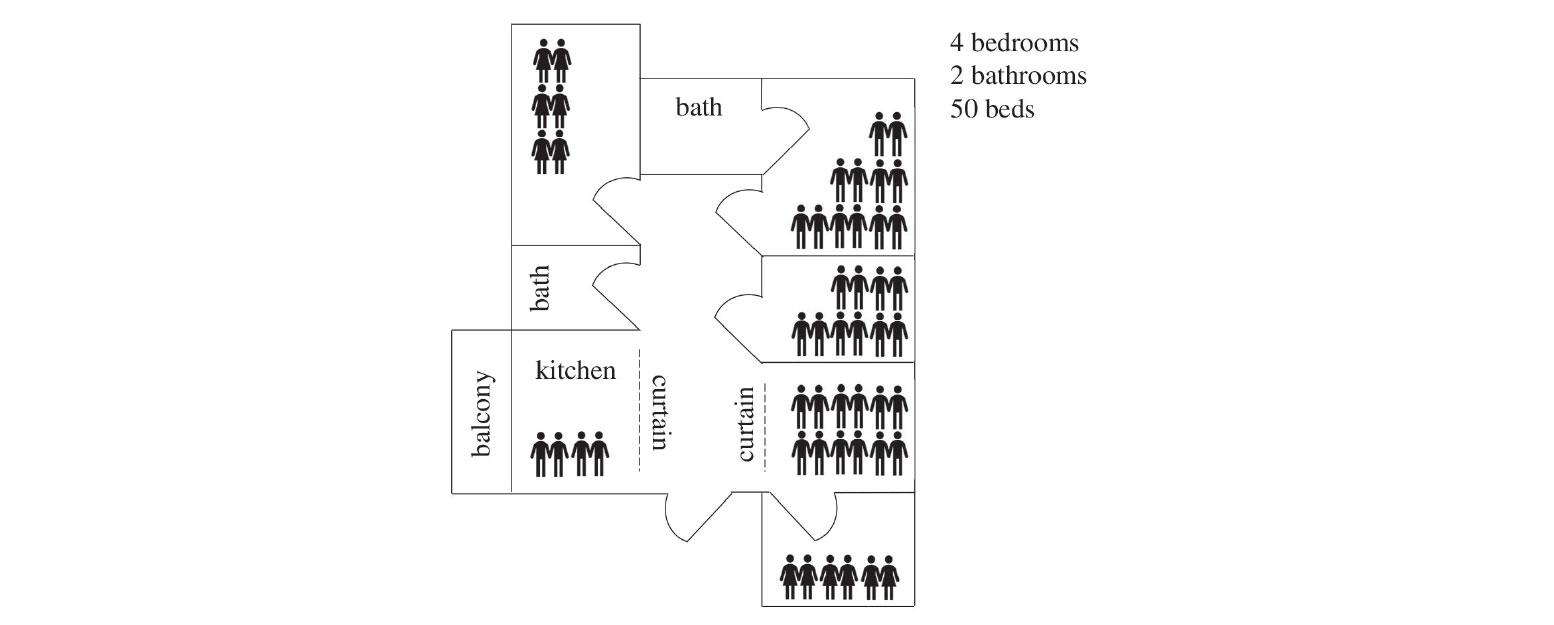

Figure 2: Apartment outline: Bed space rental housing 50 people. Source: Author sketch from memory drawn after site visit on June 28, 2016.

Shanghai's Gendered Bed Space Rentals

In "Housing Single Women" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 87, No. 1), author Julia Harten investigates emerging trends in shared rental housing in Shanghai, specifically that of bed space rentals, and their implications for gender equity.

Bed space rentals, as the name suggests, provide single beds in extremely crowded conditions. In Harten's words, "Typically 24 people are crowded into three-bedroom apartments with one or two bathrooms." Notably, kitchens are an optional amenity. These illegal rentals target recent graduates and young professionals, many of whom are migrants and can't afford any other form of housing.

To investigate how gender might shape the bed space rental market, Harten used a mixed-methods approach combining web scraping of online advertisements, apartment visits, and a 15-day stay in a two-bedroom, one-bath apartment which the author shared with 21 other women. In total, the research team surveyed 177 apartments and used data from 3,144 online rental advertisements.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Gender Disparities in the Shanghai Housing Market

Armed with this data, Harten uncovered several findings. Firstly, women paid a rental premium of almost 10 percent compared to men, as they on average chose better and less crowded apartments. However, as Harten notes, choices are rarely made in a vacuum. Rather, they are, among others, a function of what is offered. The doubly disadvantaged female migrants must balance many factors such as safety and perceived propriety when choosing an apartment. For example, women needed more space to maintain their appearance to fit cultural norms. Thus, though they were not directly discriminated against in pricing, they still effectively paid a requisite sociocultural premium on housing.

Secondly, female tenants at best are less preferred and at worst face discrimination in accessing the bed space rental market. Just 2 percent of advertised beds were in all-female apartments and evidence of prejudice was seen in interviews with landlords.

Harten's research reveals that while bed space rentals in their specific form may be contextually unique to China, more generally they are a response to housing pressures that are present in many post-industrial societies. Further, though female tenants pay the same rate for approximately similar services, they on average pay more for housing as they "select" from a scarcer and more expensive pool of housing.

These findings are evidence that many post-industrialized societies need to take more proactive steps in planning housing. Previous housing policies, especially public housing, are rooted in the circumstances of industrializing and industrialized societies of the 19th and 20th centuries. Today, however, there are new pressures and new needs, and housing policy and planning need to adjust accordingly. "Housing Single Women" adds to a body of literature disproving the neutrality of the market and society. This paper shows that as "developed" or "modern" as many societies have become, equity remains a challenge. And that the process of achieving it may not be a linear progression, but perhaps an adaptive and iteratively reflexive process.

Recognizing this begs that we take greater steps in planning to not just correct for previous wrongs but evaluate how structural inequities perpetuate and evolve. In the case of gender equity in housing, this means taking greater note of not just historic and current inequities such as disparate gender roles and incomes and how they affect housing, but also how these factors compound and intersect with arising circumstances and new contexts resulting in novel inequities.

Top image: Asia-Pacific Images Studio/E+/gettyimages.com