Uncovering JAPA

Enforcing Asian Exclusion Through Design and Planning Regulations

Land use and design regulations, while seemingly banal at face value, are deeply political and can be powerful tools to enforce racist and xenophobic ideals held by dominant communities.

In their article "Racism by Design? Asian Immigration and the Adoption of Planning and Design Regulations in Three Los Angeles Suburbs" (Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 89, No. 1), Hao Ding and Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris examine the relationship between design and land use policies and shifting racial demographics in three Los Angeles County municipalities — Alhambra, Arcadia, and San Gabriel. The three municipalities experienced an influx of Asian residents in recent years, becoming over 50 percent Asian in 2019.

Design Regulations Influence Minority Communities' Development

To examine this issue, Ding and Loukaitou-Sideris conducted a literature review of existing studies on the impacts design and land use controls have on minority, and specifically Asian, communities in the United States. They then completed archival research in the municipalities of interest and interviewed 14 planners, architects, planning and design review commissioners, and resident groups.

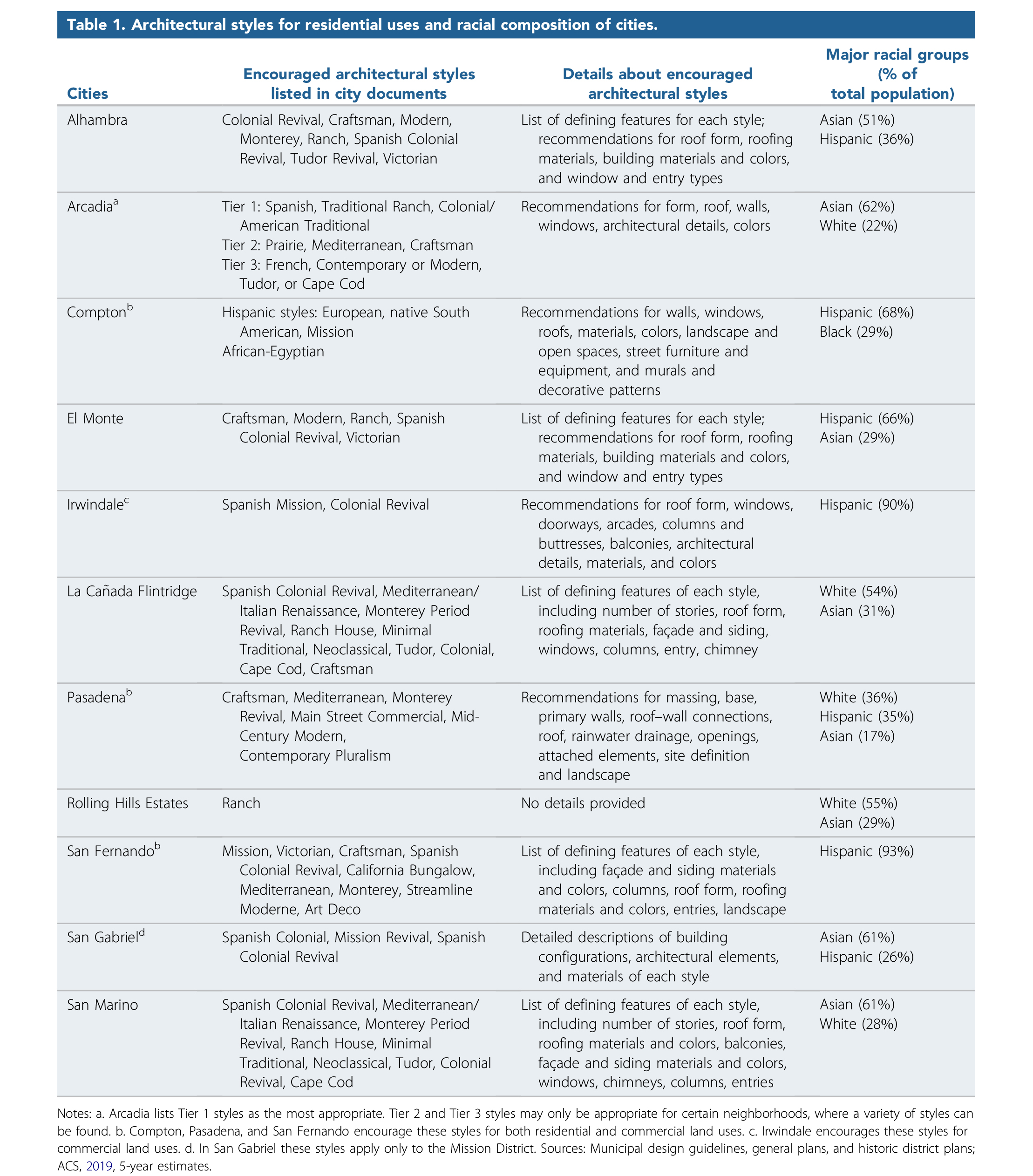

In addition to the three case study cities, the researchers examined all 11 Los Angeles County municipalities that were "majority-minority" with a singular minority group comprising at least 35 percent of the population and having citywide design regulations. Within those cities, the predominant architectural styles encouraged were Anglo-American and Spanish Colonial, leading the researchers to focus on cities with majority Asian populations instead of Hispanic to study the reasons for this lack of Asian design styles.

Through their literature review, Ding and Loukaitou-Sideris found studies of "design assimilation" prevalent in communities with growing minority populations about mansionization, architectural styles, historic preservation, and ethnic businesses. These studies demonstrated how regulations reinforced the values of dominant groups. In their examination of 11 Los Angeles County municipalities, the researchers similarly found that design regulations often promoted alignment with pre-existing development styles, preventing new styles from entering the city fabric as seen in Table 1:

Table 1. Architectural styles for residential uses and racial composition of cities.

Cultural Clashes Shape Neighborhood Architecture Debates

Within the three case study cities — Alhambra, Arcadia, and San Gabriel — many new residents had the resources to build larger homes with different styles, but existing community members expressed fear over a changing community and requested stronger regulations to curb these shifts. As a result, when the Asian population gained a majority in the 2000s, each city adopted new residential design guidelines that limited building scale for single-family housing and encouraged American and Spanish-style architecture.

Through their interviews with relevant planners and designers, Ding and Loukaitou-Sideris uncovered four predominant types of conflict between existing white residents and Asian newcomers around the built environment:

- House mass, scale, and compatibility: Many residents felt their built environment was being rapidly replaced by large mansions that threatened the neighborhood's identity. The pushback against mansionization fell almost entirely on Asian newcomers, and review boards often used "compatibility" with the surrounding community to subjectively deny developments.

- Blending in through encouraged styles: Though design guidelines are not mandatory, design review boards have the authority to reject developments if they do not blend in with the surrounding fabric. Design guidelines also police specific elements of buildings, some of which differ in taste across cultures. For example, Asians often preferred larger entrance doors that were deemed incompatible with existing styles.

- Reviving a Spanish Colonial past: Though historic preservation can be a positive tool for maintaining cultural identities, it can also be weaponized to prevent change and adaptation. In San Gabriel, a Chinese business wanted to have signage in Chinese, but people opposed the presence of Chinese characters in the historically Spanish Colonial district. The city chose which identity to preserve and excluded others from its historic narrative, holding onto this identity at the expense of other racial and ethnic identities that have since moved into San Gabriel.

- Stereotyping and chasing out massage parlors: In 2017, San Gabriel limited the number of massage parlors and spas, most of which were owned and frequented by Asians. These establishments had been wrongfully associated with illicit activities like human trafficking and prostitution based on racist stereotypes.

Selective Case Study Reveals Systemic Bias

The study findings about city planning and design as an enforcer of systemic racism cannot be generalized to all communities, given the specific focus on a few Asian-majority cities that promote Anglo-American and Spanish design styles.

Nevertheless, the study has strong implications for the implicit bias and exclusion present in what is often viewed as objective planning practices. The findings of Ding and Loukaitou-Sideris expose the use of planning and design controls as a reactionary tool to reinforce white imaginaries and colonial histories, exclude the needs of a new population, and quell their fears of a changing racial and ethnic demographic.

This study also highlights the lack of political and decision-making power Asian communities have, particularly in planning and built environment decisions. Ding and Loukaitou-Sideris suggest that planners have a role to play in balancing culturally responsive needs and tastes for newcomers and existing communities and spreading awareness of implicit biases among government bodies and community members.

Top Image: