Planning February 2018

Inclusive Mobility

Applying universal design to how people get around.

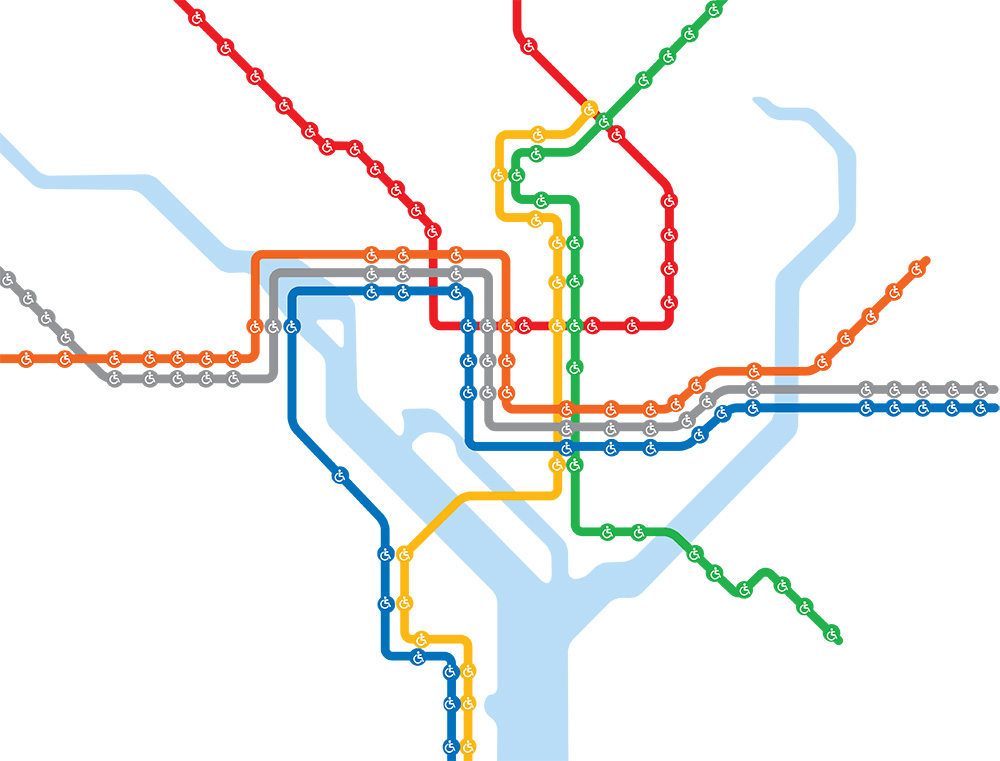

Illustration by Lana Gwinn; map source: WMATA.

By Steve Wright and Heidi Johnson-Wright

John Morris, a Florida-based travel writer (wheelchairtravel.org), uses a power wheelchair for mobility. He has explored the accessibility of dozens of public transit systems while on the road in both the U.S. and on four continents. He says that virtually every city in America has a long way to go before they truly offer inclusive mobility. "City planners often fail to recognize the true cost of accessibility barriers in transportation and movement. Just like our able-bodied counterparts, people with disabilities are on a schedule and have places to be: jobs, meetings, appointments, dinners, movies, concerts, sporting events, flights to catch, etc.," Morris says. "Barriers to accessibility disrupt freedom of movement and place additional hardships on those who use wheelchairs or other assistive devices."

People with disabilities are a signification part of the population: Nearly 16 million Americans use wheelchairs, canes, crutches, or walkers. Millions more have vision, hearing, or cognitive disabilities that impact how they get around.

Supporting the mobility of all people, regardless of ability, is arguably one of the most important urban planning issues facing public- and private-sector professionals.

John Morris at the Amputee Coalition National Convention last August in Louisville, Kentucky. Photo courtesy Amputee Coalition.

Embracing a new philosophy

From the 1950s to recent times, mobility was largely defined by the ability to buy, finance, maintain, fuel, insure, and park an individual automobile. Outside of very large, older Eastern Seaboard cities, public transit was given second-class status and streets were designed to move more cars faster — sacrificing pedestrian and multimodal mobility.

A huge shift in philosophy — to make life more affordable, accessible, and healthy — has begun to bring about a focus on universal design that aspires to give urban and suburban people who commute — by foot, by wheelchair, by bicycle, and by public transit — equal standing or priority over automobiles.

This seismic shift can have a profound positive impact on people with disabilities. The complete streets movement, which embraces wider, well-maintained sidewalks; safe, well-marked crosswalks; more accessible bus stops; and better elevator access to underground or elevated commuter rail, also facilitates universal design, giving people of all abilities increased access to housing, jobs, civic opportunities, medical care, recreation, and more.

But for the nearly 57 million Americans who have some kind of disability, challenges remain.

Well-meaning designers who seek to activate the pedestrian realm with more plantings, decorative furniture, and sidewalk cafes sometimes block the wide, accessible path of travel needed for people who use wheelchairs for mobility.

At times it's a simple lack of communication and coordination among the professional disciplines — planners, architects, traffic engineers, public works field staff, downtown development authorities, community reinvestment authorities, and private developers changing or designing rights-of-way.

And then there are ride-share and transportation network companies, like Uber and Lyft. Many planners embrace these as one answer to both traffic congestion and the conundrum of getting people to and from transit — the so-called first and last mile. But these services are provided by independent contractors who typically drive sedans and SUVs, making few ride-share vehicles able to accommodate those who use power wheelchairs or other large motorized devices.

Poorly designed sidewalk and crosswalk infrastructure make it more difficult for people with limited mobility. For example, a utility pole blocking the middle of a narrow sidewalk might not pose an issue for an able-bodied person, but a wheelchair user, a person with a walker, or a mom pushing a stroller would have to find another route, or walk in the street to get around the pole.

Likewise, a pedestrian activation button on a raised sidewalk out of the ADA-accessible part of a curb ramp makes it nearly impossible for a wheelchair user to cross under the safety of the "walk" light. Photos courtesy Perils for Pedestrians, Pedestrians.org.

Making transit inclusive

For more than half a century, Los Angeles has been famous (some would say infamous) for being the most car-centric place in the Western world. That makes getting around a lot harder for people with disabilities. Accessible consumer van upgrades — adapting for lifts, ramps, safety tie-downs, and automated systems that allow for transfer from a wheelchair to the driver's seat — can cost upward of $75,000, and thousands more per year to fuel, maintain, insure, and park.

But all of that is changing with development of the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority's 105-mile Metro Rail system. In 2016, county voters approved a sales tax that will generate nearly $1 billion per year for transit and related improvements. Measure M, the dedicated tax, will roll out another 32 miles of rail service in the next decade alone — all of it fully accessible. At full build out, Measure M could potentially double the rail network in Los Angeles County, and add bus rapid transit lines and pedestrian infrastructure.

One hundred percent of the Metro Rail train stations are wheelchair accessible under the Americans with Disabilities Act, thanks to elevators or boarding platforms with gently sloped ramps at all 93 stations.

That isn't the case for older, legacy systems, notes research published in London's The Guardian. In Paris, nine of 303 metro stations are fully accessible and only 50 out of 270 London Tube Stations are. New York gets a poor grade, too, with just 117 of its 472 subway stations fully accessible.

But progress is being made in other major U.S. cities. Washington D.C.'s 91 Metro train stations are 100 percent accessible, and in Chicago, where some elevated and other rail stations were built long before the ADA was passed in 1990, 67 percent of the Chicago Transit Authority train stations are fully accessible to people with disabilities.

"We need to design transit systems that everyone in a community — regardless of money, or physical or cognitive ability — can use," says Jana Lynott, AICP, manager of AARP's transportation research agenda.

Fixing the first and last mile

But transit is only one part of mobility. Another challenge is bridging the gap between where riders live and work and the stations they might use.

"People who have mobility constraints really need access to transit," says Bill Delo, AICP. "They are a big market for transit ridership — but only if they can get from their home to transit to their place of work, on wide sidewalks with safe crosswalks."

Best Practices from LA

The First Last Mile Strategic Plan addresses multimodal access and the need to design in a way that mainstreams people with disabilities.

The plan advocates for universal design, stating: "Most public transportation stations, trains, and buses are accommodating to manual wheelchair users; however, they have historically been treated as an isolated group, with limited number of spaces on buses.

"As the population ages and more manual and electric wheelchair users ride public transit, new seating configurations and storage may be required. Sidewalks and routes to transit nodes must maintain smooth and clear rolling surfaces, accessible curb ramps, and signal times conducive to safe street crossings."

LA County tackled this head-on when it adopted the First Last Mile Strategic Plan (tinyurl.com/ya68mr7n) in 2014. The plan focuses heavily on inclusive design to serve people with disabilities. The progressive, innovative plan was honored with the American Planning Association's 2015 National Planning Excellence Award for Best Practice (www.planning.org/awards/2015/firstlastmile.htm).

Delo, who led the project for the Irvine office of IBI Group, a Canadian-based, technology-driven urban design and engineering firm, notes that universal design should be inclusive of the needs of a great span of mobility.

"We looked at this as an opportunity to go beyond the typical mobility plans that look at bike and pedestrian mobility then stop ... to increase access for people who use wheelchairs, scooters ... even skateboards," he says. "We wanted to improve accessibility for everyone who commutes by transit [in] Los Angeles."

Delo says that a key to a better first- and last-mile experience is widening sidewalks and making sure they are well maintained. "People have many different ways of getting around without a car, but they all — other than bicyclists — are restricted to the sidewalk."

Sidewalks in LA are narrow in some places, and many have cracks, gaps, and obstructions or are poorly maintained, he adds. The plan acknowledges this and recommends replacing insufficient sidewalks, but doesn't include an implementation strategy or funding to do so. (The problem of absent and insufficient sidewalks is hardly limited to LA, although the authors know of no national database that tracks sidewalk statistics.)

Communities too often wait for private redevelopment to improve sidewalks along transit corridors, Lynott says, instead of initiating improvements to rights-of-way. This often means neighborhood connectivity fails to meet minimum standards.

"I see many communities that need to invest in access for people with disabilities to both public transit and sidewalk networks. And they need to have Americans with Disabilities Act transition plans that are updated on an ongoing basis," says Lynott.

An ADA transition plan is a state or local government's self-evaluation of its facilities, programs, and services to assess whether the government is in compliance with ADA rules. Problems and shortfalls are identified and a plan is put in place — with action steps and deadlines — to address them. "Transition plans serve to connect people with disabilities to jobs and services," she says. "This has a direct, positive economic impact."

Venice Boulevard in Venice, California, now provides shorter pedestrian crossings, mid-block crosswalks with signaling buttons, narrowed traffic lanes, protected bike lanes, and other complete streets features that make it safer for all pedestrians, including those using assistive mobility devices. Photo courtesy LADOT.

Beyond the ADA

Gabe Klein earned a national reputation for being an innovator who favored inclusive mobility, focusing on putting people before automobiles on city streets, when he ran two of the largest transportation departments in the U.S.: Washington D.C., then Chicago.

According to Klein, far too many agencies and planners still look at design for people with disabilities as a last-minute item, even on a new project.

"I think when agencies focus only on the Americans with Disabilities Act, they can get too focused on just meeting minimum ADA requirements. That's when we lose track of truly making a place accessible for people with disabilities," says Klein, cofounder of CityFi, an advisory services platform for urban change management, and author of Start-Up City: Inspiring Private and Public Entrepreneurship, Getting Projects Done, and Having Fun.

"In Chicago, I had a great relationship with the Mayor's Office for People with Disabilities," he says. "We focused on practical solutions. We didn't want to just look at numbers in a book, we wanted to have people with disabilities come in and help with our design from the ground floor. That way, you didn't just have a ramp to meet the ADA laws, you had a ramp that functioned, even in the Chicago winters."

"When we came up with our complete streets guidelines, the idea of designing for people with disabilities wasn't an afterthought. It was a priority to design inclusively from the start, because we found if you design for people with disabilities, the able-bodied people will be just fine," he adds.

In 2015, the National Complete Streets Coalition, a part of Smart Growth America, published "Complete Streets Help People with Disabilities." The complete streets approach, says Emiko Atherton, the coalition's director, "means that transportation decisions, plans, and procedures are aligned and designed to accommodate all users of all abilities."

The two-page guide notes that "Complete Streets policies provide flexibility to transportation professionals and give them room to be creative in developing solutions that promote accessible travel," noting that designers should think about important details at intersections (like audible or tactile signals for blind pedestrians); smooth, obstacle-free sidewalks; and ample space to wait and board safely at transit stops.

Further, such policies "remove barriers to independent travel by considering the needs of all users at the outset of every transportation project," the guide reads. Considering all users helps keep people connected, which improves livability, and can reduce "dependence on more costly alternatives, such as paratransit or private transportation service."

According to Lynott, communities that want to make a real commitment to providing effective, inclusive mobility must take compliance with the ADA seriously. They need to educate staff in planning and other departments about the standards and about universal design to align those concepts in zoning, development review, and comprehensive planning.

"It's one thing to understand the law and the regulations, but another to understand the design experience. All of us as planners need to wrap our heads around the principles of universal design and think through what that means," says Lynott.

Seattle Department of Transportation engineer Johanna Landherr uses a wheelchair to test a new curb ramp. Photo courtesy SDOT.

Looking past the curve

Everything about transportation — both urban and rural — will likely be transformed over the next decade. Disruptive transportation technologies are already changing the landscape. Some say suburban transit service will disappear altogether.

Benjamin de la Pena is the deputy director for policy, planning, mobility, and right-of-way at the Seattle Department of Transportation. The agency just published the New Mobility Playbook (newmobilityseattle.info), a planning document that addresses rapidly evolving transport technology (like autonomous vehicles), app-based transportation network or ride-share services (Uber and Lyft), car-share firms (Zip Car and Car2Go), and private-sector microtransit start-ups that use vans or small buses to transport passengers.

"One of our chief concerns is equity, says de la Pena. "The city has a very robust equity plan and our concern about these new options is that they offer mobility."

He notes that ride-share companies currently offer few options for people who use power wheelchairs. He wants autonomous vehicle technology to consider disabled users, too.

The playbook's suggested solution is to develop a "Wheelchair Accessible Taxi program to reduce operating costs, meet customer expectations, and work more efficiently across jurisdictional boundaries." The playbook acknowledges that while much of tech-driven new mobility is owned and operated by the profit-minded private sector, government "must ensure that shared mobility services provide dignified, reliable, and affordable transportation options that are accessible to all."

Further, the New Mobility Playbook notes that "mobility options and technology must fight against the displacement of vulnerable communities and develop the living wage transportation workforce of tomorrow," and its Strategy 1.1 notes that best practices for cities and regions grappling with the onslaught of smartphone-app-driven mobility must "advance shared mobility equity programs targeting people of color, low-income, immigrant, refugee, youth, and aging populations, women, LGBTQ, and people with disabilities."

Working directly with people of diverse abilities also helps inform the planning process in Seattle. Inclusion is not only a best practice, it is required, notes de la Pena. The city's advisory boards "have members who use wheelchairs for mobility, people with low vision, people with other disabilities. And we listen to them."

De la Pena urges other cities to include significant input from community members with disabilities when designing and implementing inclusive mobility initiatives.

It's a practice John Morris certainly advocates.

"ADA compliance consultants should have a personal experience with disability and be able to understand the needs of the disabled population," he says. "In larger cities with a large population of disabled citizens, multiple consultants should be brought on board, each specializing in an area of accessibility, but also participating in team planning and discussions."

"The perfect ADA team," he adds, "might include a wheelchair user, deaf/blind expert, and an expert in intellectual disabilities."

Steve Wright is an award-winning journalist and the communications leader for PlusUrbia Design. Heidi Johnson-Wright is an attorney specializing in ADA issues. She has used a wheelchair for mobility for more than 40 years and frequently lectures on the intrinsic value of universal design and inclusive mobility.

Resources

Metro: A Customer's View: A wheelchair user navigates the bus and rail system in LA. youtu.be/QE12ktreN2c

LA County's First Last Mile Strategic Plan: tinyurl.com/ya68mr7n

Smart Growth America/National Complete Streets Coalition's "Complete Streets Help People with Disabilities:" tinyurl.com/yb9z9ctf

AARP's Planning Complete Streets for an Aging America: tinyurl.com/y8ckxblv

Seattle's New Mobility Playbook: tinyurl.com/y7vjbssb

The Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Access at Buffalo: idea.ap.buffalo.edu