Uncovering JAPA

Revisiting Arnstein’s Ladder: Justice as Parity of Participation

Given government rollbacks on one hand, and new challenges posed by escalating climate change on the other, how should planning adapt to support public engagement?

In "Justice as Parity of Participation" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 85, No. 3), Gwendolyn Blue, Marit Rosol, and Victoria Fast suggest that if participation is to remain a meaningful strategy for empowering underrepresented groups, it will necessarily have to include attention to the question of justice.

Justice in Participation: Redistribution, Recognition, Inclusion

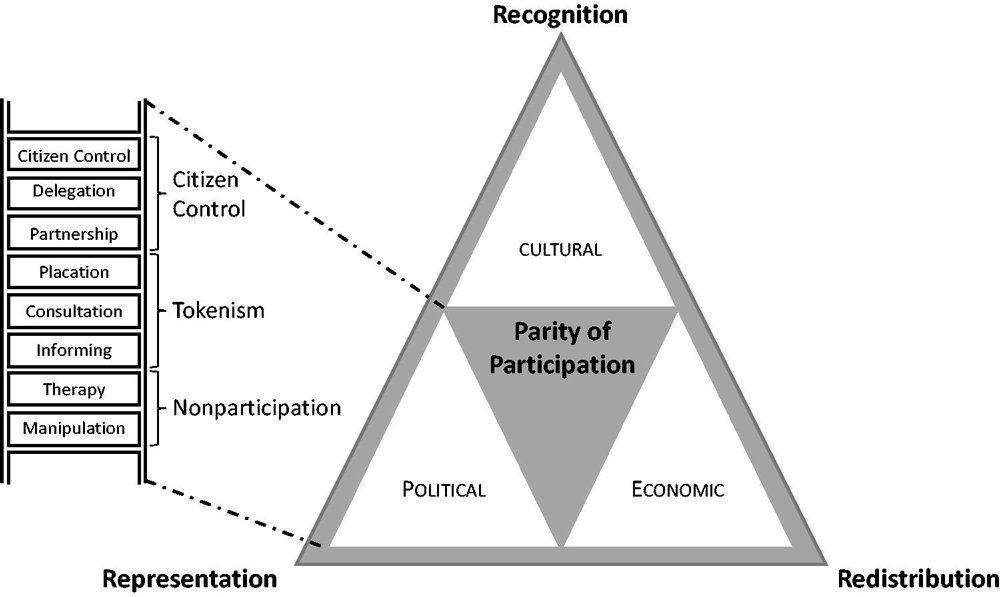

The authors offer a conceptualization of justice that simultaneously addresses redistribution, recognition (cultural justice), and participation (procedural justice). This tripartite framework holds significance for local and transnational environmental governance processes and informs climate justice movements.

Five decades after Sherry Arnstein's work linked citizen participation with redistributing power between state institutions and the citizenry, participation has become a key component of the planning process.

As the JAPA authors acknowledge, much has changed since Arnstein made a case for equitable participation. Today, the emancipatory potential of community participation is widely recognized across social groups and the planning profession.

Yet, while the scope of participatory practice has expanded and the top-down role of government institutions has diminished, inequitable social structures continue to exclude underrepresented groups from meaningful participation.

This, in part, is due to a missing link. According to the authors, participatory planning and social justice outcomes are not connected to a conceptual framework that can inform practice.

The paper has a dual agenda — to fill a gap in participation literature and develop a framework for action for participatory practice. The concept that underpins the authors' analysis is Nancy Fraser's (1997, 2009) model of justice which sits at the intersection of redistribution, recognition, and representation.

Drawing on Fraser's three dimensions of justice, the authors develop a "sensitizing device." They make a case for reconceptualizing Arnstein's participatory framework that simultaneously addresses cultural, economic, and political dimensions. Taking this into account is crucial, they argue, if planning is to move away from the technical and procedural aspects of participation, and toward participation with a transformative effect on social equity.

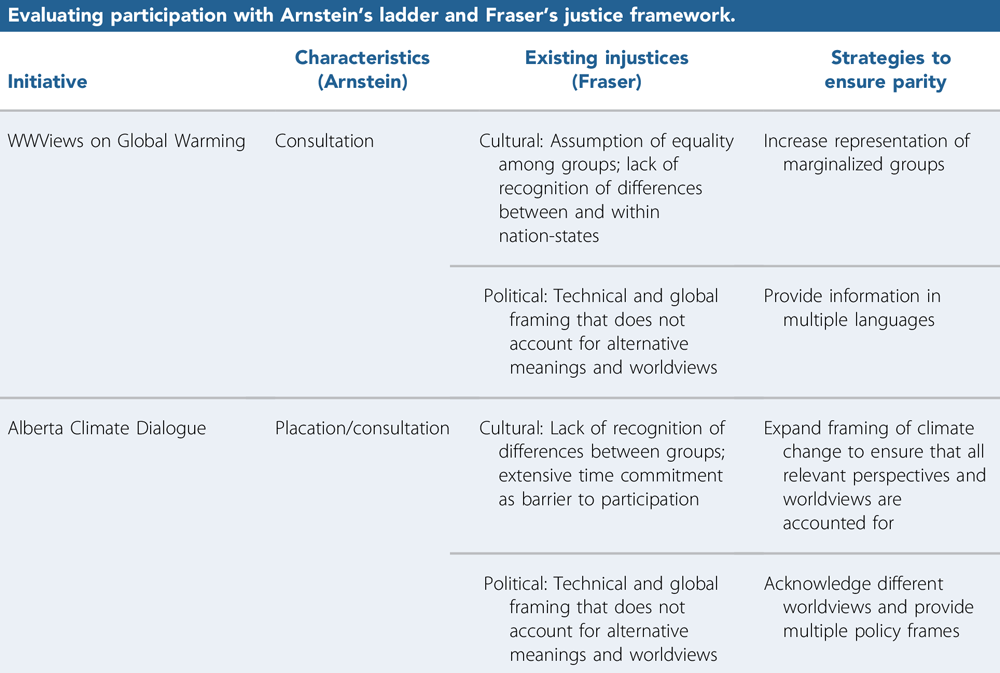

Evaluating participation with Arnstein's ladder and Fraser's justice framework, from "Justice as Parity of Participation" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 85, No. 3).

Address Framing, Acknowledge Diverse Worldviews

One of the more challenging aspects of participation is framing, a concept that Fraser links to representation. Even in cases in which diverse groups are equitably represented in the decision-making process, how policy agendas are framed can result in excluding diverse and divergent world views. The JAPA authors recommend that planners "[b]roaden participation in defining policy agendas by acknowledging diverse worldviews and forms of cognitive authority, allowing reframing of issues."

However, as the authors recognize, conflicts can and will arise from attending simultaneously to the three dimensions of justice. Susan Fainstein (2000) has cautioned that a focus on "consensus," suppressing conflict in participative planning, reproduces systemic inequalities. This shows the limits of theoretical models of justice and brings into focus the potential of practice-oriented tools, such as the authors' strategies for action:

Strategies for participatory action, from "Justice as Parity of Participation" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 85, No. 3).

It is at this intersection between practice and theory that the authors situate their examples from public engagement in climate change initiatives such as World Wide Views on Global Warming and the Alberta Climate Dialogue. One of the most important insights from the authors' case studies is that an inflexible framing of the climate agenda played a key role in marginalizing diverse points of view in the World Wide Views on Global Warming talks and the Alberta Climate Dialogue.

They recommend that planners "[e]xpand framing of climate change to ensure that all relevant perspectives and worldviews are accounted for."

However, giving voice to diverse and previously excluded groups will not always result in progressive outcomes.

This is particularly relevant for how the climate crisis is framed today, as false equivalency has made way for perspectives that work against scientific consensus to stifle climate action.

Top image: Gathering in Japan for the World Wide Views on Global Warming talks in 2015. Photo courtesy World Wide Views media package.