Uncovering JAPA

Linking Transportation Equity and School Choice Policy

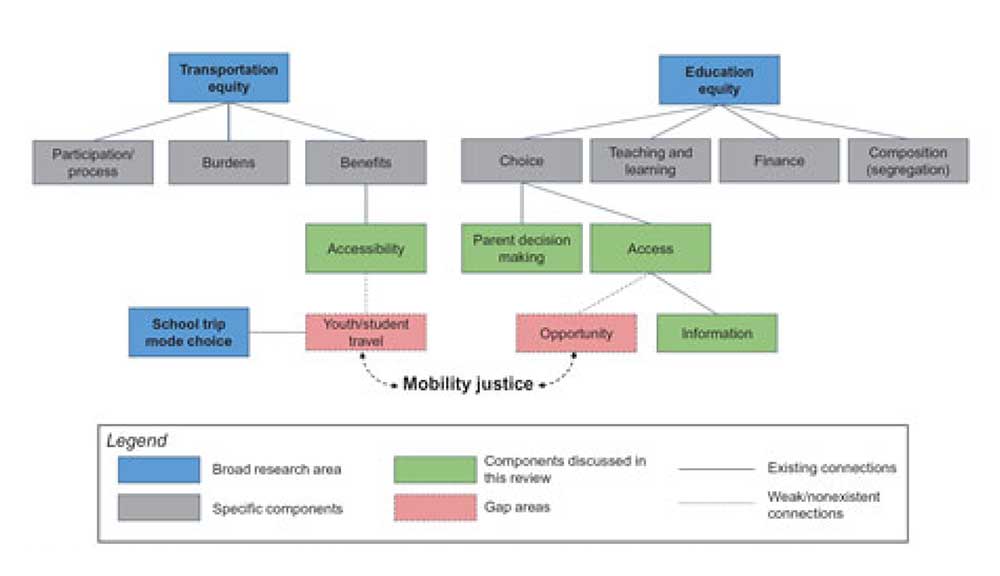

Conversations on transportation equity do not play a large enough role in the discussion of school choice policy, nor do youth/student travel enter often enough into the transportation equation, according to Bierbaum, Karner, and Barajas in "Toward Mobility Justice: Linking Transportation and Education Equity in the Context of School Choice" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 87, No. 2). The authors argue transportation and education equity must both be prioritized to achieve mobility justice, integral to school choice policy.

Transportation Equity Crucial for Justice

The mobility justice perspective sees inequality in transportation, such as travel time and ease of travel, as a feature of an exploitative system, which values certain populations over others. Some groups do not have a say over when and how they move, like refugees and domestic violence survivors, while others have total control. Youth and students have little flexibility when it comes to transportation, particularly if they rely on public transportation. To achieve mobility justice, planners must focus broadly on mobility issues at a variety of scales, such as confronting the low access to opportunities by carless individuals, regional transportation networks, and the national and global environmental impacts of travel.

Figure 1: Schematic map of the mobility justice framework concerning transportation and education equity.

Transportation Links to Education, Equity Emphasized

The mobility justice framework links transportation to education equity because the ideal of school choice has travel implications. Those who do not have high access to fast, straightforward transportation options have fewer real school choices. The authors note that parents of color are more likely to select schools that are closer to home, and students with longer commutes had slightly higher rates of absenteeism in certain cities than students with shorter commutes.

The article's authors offer suggestions for integrating mobility justice into education policy. For one, they recommend a renewed focus on the quality of neighborhood schools. As for choice schools, like magnet schools and charter schools, policy administrators should use a broad array of metrics and account for racial disparities. In the mobility justice framework, Bierbaum and co-authors stress local knowledge as a source of data, insisting on giving a voice to students and parents so that researchers understand the true embodied practice of travel to school.

Mobility justice highlights the need for interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral planning, themes that guide my education and practice. Education equity is not achieved without considering transportation equity and mobility justice, as well. Similarly, as a student in public health nutrition and planning, I believe that health equity is not accomplished without inputs from multiple sectors, like planning and education, and food justice is necessary for the success of nutrition interventions. In addition to being multisectoral, the mobility justice framework is multi-dimensional, reaching beyond municipal borders and commanding a regional approach, like with food justice and food systems. Throughout the article, the authors make a strong case for the close integration of multiple sectors to advance policy equitably, an argument that applies to many matters in planning.

Top Image: SDI Productions/E+/gettyimages.com