Uncovering JAPA

Decriminalizing Vehicular Homelessness in Los Angeles

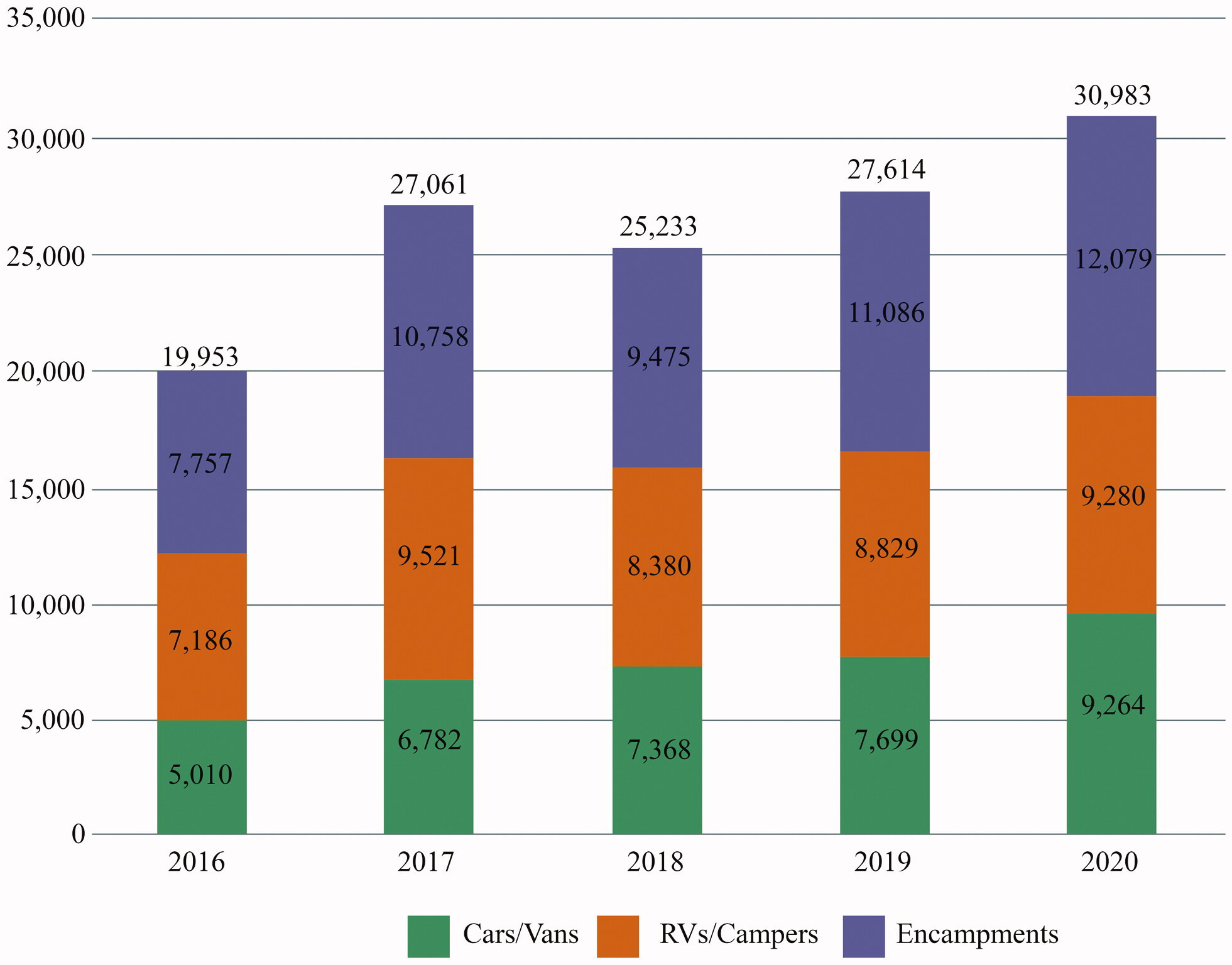

Pushed by the affordable housing crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic and pulled by the relative safety and security of cars to public spaces or temporary shelters, Los Angeles saw a 55 percent increase in vehicular homelessness from 2016 to 2020. In "Planning For and Against Vehicular Homelessness: Spatial Trends and Determinants of Vehicular Dwelling in Los Angeles" (Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 89, No. 1), Christopher Giamarino, Madeline Brozen, and Evelyn Blumenberg explore the relationship between municipal vehicle ordinances and vehicular homelessness in the Los Angeles Continuum of Care, which includes all of Los Angeles County except Glendale, Long Beach, and Pasadena.

Research Questions Vehicular Homelessness Regulations

The authors pose two research questions:

How do the municipalities in the Los Angeles Continuum of Care regulate vehicular homelessness?

What is the relationship between the severity of vehicular ordinances and the prevalence of vehicular homelessness?

Concerning vehicular regulations, the researchers analyze vehicular ordinances in 85 municipalities. They categorize them as citywide bans (44 cities), overnight parking restrictions (26 cities), permit requirements (12 cities), time restrictions (12 cities), zone ordinances (9 cities), or no ordinances (4 cities). They then examine the relationship between the type of vehicle ordinance and the prevalence of vehicular homelessness by census tract, using data from the annual point-in-time count.

Figure 1: Unsheltered Homelessness Trends in the Los Angeles Continuum of Care, 2016-2020

Figure 2: Vehicular ordinances by type

Restrictive Ordinances Shift Vehicular Homelessness, Study Finds

Consistent with intuition, the researchers find that "census tracts with the most restrictions on vehicle dwelling contained fewer people sleeping in vehicles than other tracts with fewer or no restrictions." They also find a positive spillover effect for census tracts adjacent to those with citywide or overnight bans but not with permit requirements or zone ordinances. The authors conclude that restrictive vehicle ordinances do not reduce the prevalence of vehicular homelessness but "simply shift vehicle dwellers to adjacent communities."

Rather than criminalizing vehicular dwellings, they argue that cities should implement Safe Parking Programs (SPPs) like those of Santa Barbara and the City of Los Angeles. Leveraging underutilized parking infrastructure, SPPs "provide people living in vehicles with a legal place to sleep overnight," replete with food, social services, and a pathway to longer-term housing.

However, the authors concede that SPPs have incited neighborhood opposition and have "been used to justify increased enforcement of vehicle dwelling ordinances." In addition to targeted outreach, I would suggest that cities consider meeting people living in vehicles where they are with neighborhood-level, drive-through social service provision. This is a model with which cities have gained familiarity during the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of testing and vaccination.

Top image: iStock/Getty Images Plus — David Hagerman