Uncovering JAPA

Historic Districts and Housing Goals: A Case Study of Two L.A. Neighborhoods

How does historic preservation interact with housing goals? Historic districts serve as zoning overlays that shape urban form; however, limited analysis exists on how these districts intersect with other land use regulations.

In "Where Preservation Meets Land Use Regulation: Historic Districts in Los Angeles" (Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 91, No. 3), Sarah L. Mawhorter and Kelly L. Kinahan present a comparative case study of two Los Angeles neighborhoods undergoing the historic district designation process.

The City of Los Angeles's push to designate historic preservation overlay zones (HPOZs) in the mid-2010s was one of three initiatives aimed at addressing residents' concerns about neighborhood-level issues — particularly demolition and the construction of large single-family homes.

The other efforts included reforming the citywide Baseline Mansionization Ordinance (BMO) and recreating an overlay to regulate the square footage of new construction and remodels. Although each process progressed at a different pace and scale, all worked toward aligned goals.

The authors examined land-use rules, development patterns, and the arguments of both supporters and opponents of historic districts to understand the justification for historic preservation and the factors that led to the proposed districts' adoption or withdrawal.

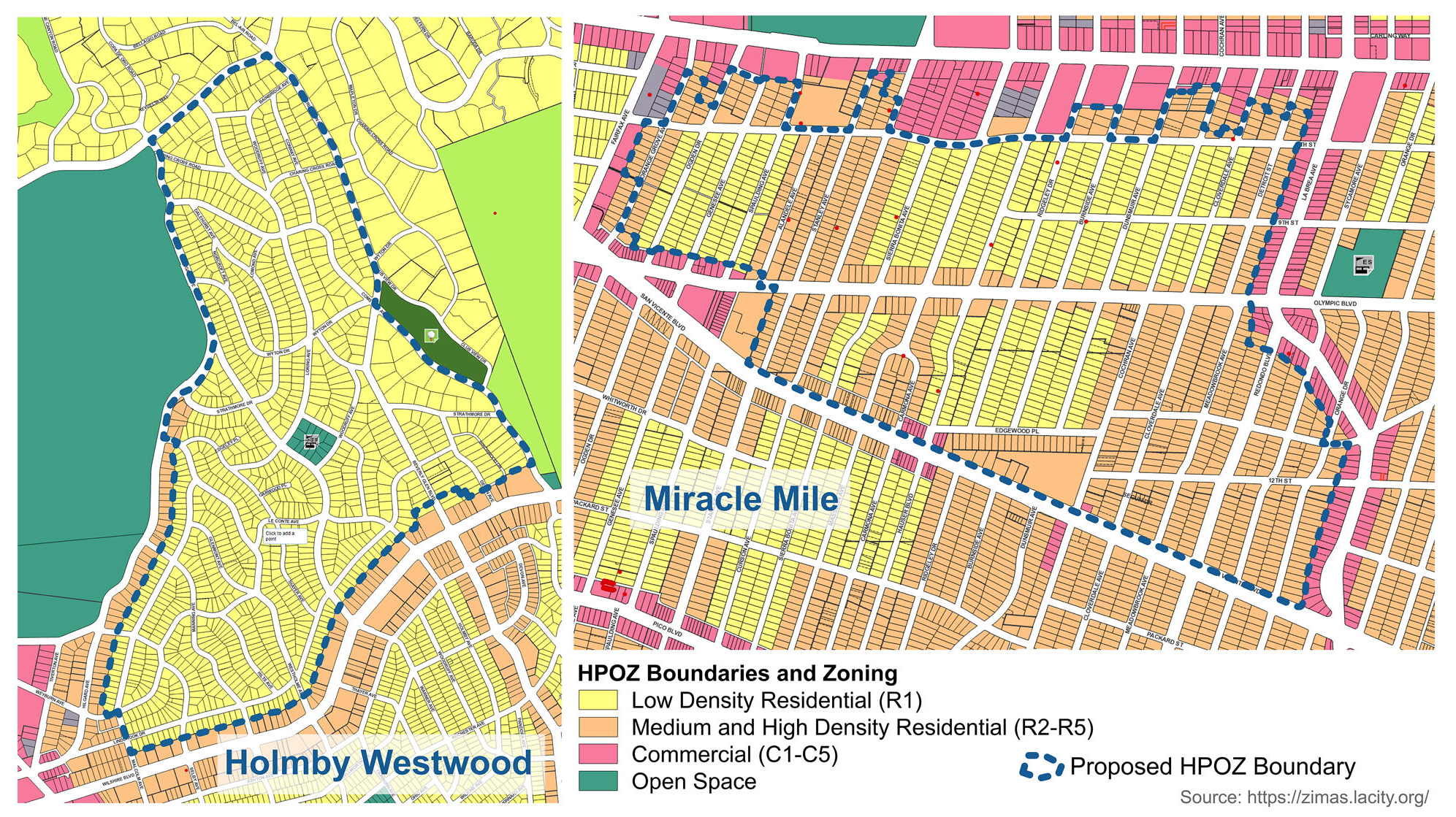

They draw important lessons about the relationship between zoning and preservation by comparing the designation process in Holmby Westwood, where the district application was withdrawn, with that in Miracle Mile, where the district was requested and approved.

The Holmby Westwood subdivision, located between the UCLA campus and the Los Angeles Country Club, contains approximately 1,100 single-family homes, many built between the 1920s and 1950s. Compared with citywide trends, the neighborhood is whiter, wealthier, and has significantly higher median rents and home values.

Miracle Mile features quiet residential streets with a mix of single-family homes, duplexes, and small apartment buildings situated between three major boulevards. The neighborhood is racially and ethnically diverse and composed primarily of renters whose median incomes, rents, and housing values exceed citywide averages but remain lower than those in Holmby Westwood.

Zoning's Role in Preservation

Holmby Westwood is zoned almost entirely for single-family development, whereas Miracle Mile permits a range of uses and densities.

These zoning differences were central to the historic district decisions. In Holmby Westwood, opponents of the historic preservation overlay zone (HPOZ) argued that the proposed Baseline Mansionization Ordinance (BMO) would sufficiently protect the neighborhood from unwanted development, as it would apply to all parcels zoned for single-family use.

In Miracle Mile, supporters of the historic preservation overlay zone (HPOZ) noted that the Baseline Mansionization Ordinance (BMO) would not apply to parcels zoned for multifamily development.

Zoning designations of lots in each neighborhood's proposed historic district.

Historic District Opposition Motivation

HPOZ opponents in both neighborhoods stressed that the HPOZ review process would restrict homeowners' property rights to renovate, expand, and profit from their homes. This argument carried even more weight in predominantly owner-occupied Holmby Westwood than in Miracle Mile, where most residents are renters. An analysis of building permits reveals high rates of addition permits in Holmby Westwood compared with both Miracle Mile and the City of Los Angeles overall.

These findings align with public comments suggesting that affluent homeowners successfully opposed the historic preservation overlay zone (HPOZ) to avoid restrictions on their ability to modify their homes.

Preventing Development and Displacement

In Miracle Mile, the historic district adoption process began in May 2014, led by the Miracle Mile Residential Association. Both renters and landlords expressed interest in preserving the neighborhood's character, opposing demolitions, and the construction of larger rental developments. Renters were specifically motivated to protect existing affordable units, finding other measures insufficient.

The residential association hired an experienced historic preservation consultant, held community meetings, produced promotional videos, and promoted the district proposal through email newsletters, blog posts, and social media. Supporters of the Miracle Mile historic preservation overlay zone (HPOZ) most frequently argued for preventing urban growth and development, emphasized the strength of historic district provisions in securing neighborhood control, and highlighted the inadequacy of other regulations.

Unlike other studies in which preservation tools were used to retain power and privilege amid rapid demographic change, the authors observed little targeted language in the Miracle Mile designation effort. They attribute this to the neighborhood's existing diversity.

Surprisingly, arguments concerning development, affordability, and property rights dominated the discussion, while historic preservation concerns were rarely mentioned.

The case of Miracle Mile illustrates how preservation tools can serve both anti-development and anti-displacement advocacy, combining internally competing logics within diverse coalitions. While opposing the addition of new rental housing, the coalition also expressed concern about affordability for existing renters — mirroring the tendency to privilege incumbent residents, a pattern common among other "neighborhood defenders."

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Residents weigh historic districts against other land use tools, often prioritizing development and property rights over preservation.

- Historic district designations can unite diverse coalitions around concerns like development and displacement.

- Preservation planning should address housing production and rental affordability, acknowledging potential conflicts with broader housing goals.

- Rather than creating new housing analyses, preservation efforts can align with general and community plans.

- Historic districts don't have to exclude denser housing types like small-lot subdivisions, multifamily units, or ADUs.

Top image: Photo by iStock/Getty Images Plus/ halbergman

ABOUT THE AUTHOR