Uncovering JAPA

How COVID-19 Redefined Urban Public Space

During COVID-19, U.S. city streets transformed into pop-up parks, bike-friendly avenues, bustling car-free zones, and street cafés. At various points during the pandemic, New York City opened 83 miles of streets and permitted more than 12,000 open restaurants. While these interventions were intended to encourage socially distanced economic activity, the policy spurred speculation about the post-pandemic future of urban streets.

In "COVID Street Cafés: Assessing Policy Windows in Five North American Cities" (Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 91, No. 3), Jason Brody, Kelly Gregg, and Paul Hess interview practitioners and analyze policy documents to understand how cities implemented street café programs and whether the move represented an adaptation of existing policies or a hard shift.

Rethinking the Role of Streets

The authors examined the implementation of COVID-19 street café programs as a potential window into allowing social and commercial uses in street space generally reserved for mobility. To measure these programs in Seattle, Los Angeles, Chicago, Toronto, and New York City, they layered different approaches that informed one another. They identified themes using news articles, conducted semi-structured interviews with city staff and stakeholders, and analyzed municipal websites to construct a record of street café programs.

Variables measured included the number of street installations, relationship to pre–COVID-19 policies, design policy, program administration, seasonality, and steps toward permanent programs (as of February 2024).

Urban form, existing policy, emergency program administration, and café design and experimentation all influenced outcomes. These COVID-19–era programs led one city to initiate a new street café program. In two other cities, they accelerated the implementation of recent policy initiatives.

Meanwhile, the experience in the final two cities was ambiguous. Despite some overall commonality, each city's street cafés followed distinct paths before, during, and after COVID-19. This had implications both for the success of the programs themselves and for how COVID-19–era emergency programs could inform permanent ones.

Street cafés on Ballard Avenue in Seattle, Washington. (Credit: Demetra Barbacuta)

Innovation in Curb Space Management

All five cities had sidewalk dining ordinances that informed the policy governing COVID-19–era programs. However, these cities had diverging policies regarding curb use prior to the pandemic. These differences affected pandemic-era policies. For example, Chicago's privatized parking management limited the city's implementation of curb cafés.

Seattle, on the other end of the spectrum, had already instituted a pilot curb café program starting in 2015, which informed its pandemic-era policy. Moreover, Seattle's COVID-19 program mandated that café spaces be open for public use when restaurants were closed.

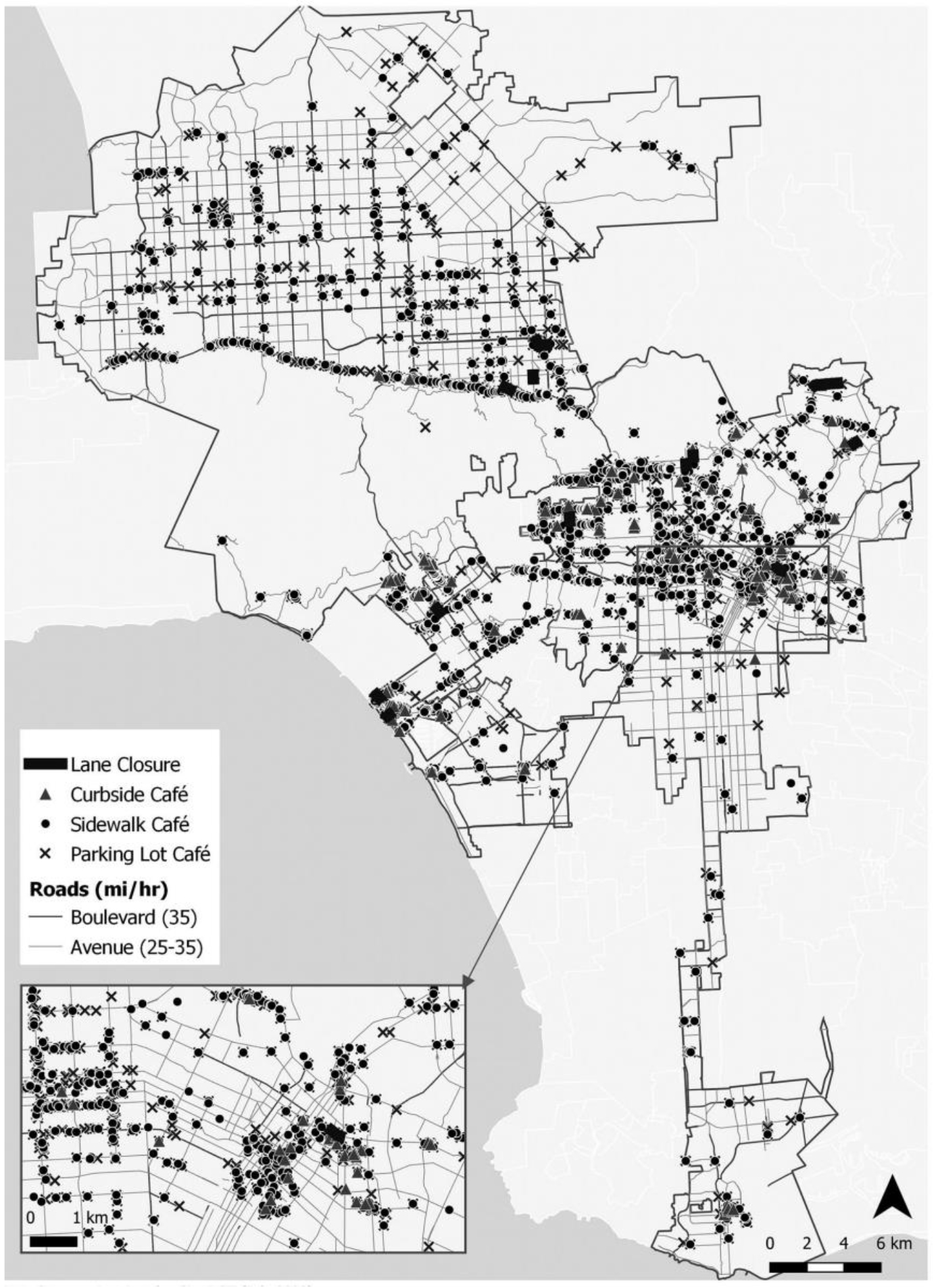

Figure 2: Locations of Los Angeles' COVID street café program, including locations on private lots, sidewalk dining, curb café, and street lane closures. (Credit: Christa Yeung, based on data from the City of Los Angeles Department of Transportation)

Long-standing policies allowing the temporary closure of streets for block parties or street festivals informed COVID-19–era street closures. Predecessors included New York City's Summer Streets and Los Angeles's CicLAvia, which periodically closed streets to vehicular traffic to support walking and biking.

Seattle's and Toronto's recently updated comprehensive street management policies were instrumental to their respective COVID-19 programs. Policies for regulating outdoor dining in curb space in Los Angeles and New York had to be developed from the ground up. Across the cities, few shared café spaces and streetwide installations were both widely implemented and renewed over multiple years.

COVID-19 street cafés offer a test case for managing curb space for social use. Despite similar objectives, the implementation of street café programs played out differently in each city. Some cities adapted existing programs and policies. Most worked to suspend fees, reduce permitting burdens, and extend programs to underserved communities. These efforts were critical to making street café programs work during the pandemic, and staff consistently framed fee suspension as an effort to promote equity.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Recently adopted street policies shaped emergency responses.

- Rapid design solutions generated a range of experimental approaches, including open-source plans for permittable street cafés.

- Most cities made only minor adjustments to the bureaucracies responsible for administering café programs.

- Planners can renegotiate emergency actions to reduce barriers to street café implementation and sustain programs.

Top image: Photo by iStock/Getty Images Plus/ pixdeluxe

ABOUT THE AUTHOR