Crafting Charrettes That Transform Communities

PAS Memo — November/December 2018

By Holly Madill, Bill Lennertz, and Wayne Beyea, AICP

If you gather 10 planners in a room and ask them to describe a charrette, you will most likely get 10 different versions of what is actually done and 10 different opinions on how effective it is at engaging a community. So what precisely is a charrette?

Having held hundreds of charrettes over 30 years of practice, the National Charrette Institute (NCI) defines a charrette as a multiday community engagement event where stakeholders and decision makers work alongside experts to co-develop solutions to built environment problems using design. Although traditionally applied to community design and planning work, it is also being used in policy and organizational planning efforts.

When the right people are engaged at the right time, with the right information and in the right place, charrettes can build trust and provide the space for people to work together to solve divisive issues and create successful projects (Figure 1). Charrettes have the power to ignite transformation in communities — but without careful preparation they can backfire, leaving feelings of distrust in their wake.

Figure 1. Charrettes provide a space for people to work together to solve divisive issues and create successful projects. Photo courtesy NCI.

This PAS Memo defines and describes the NCI Charrette System approach and offers guidance on when and how to incorporate this process and tool into planning work. A case study from the college town of Norman, Oklahoma, provides an illustration of the power of this process in overcoming planning challenges.

Overcoming Community Planning Challenges With Charrettes

Community planning work is done in a complex and contentious world. The NCI Charrette System approach excels in these environments by establishing trust among disparate groups, creating space for community members to work alongside decision makers and experts in solving big practical problems, and illustrating possible scenarios to alleviate the fear of change, all in a condensed time frame that can save money and certainly time.

Community planners face many challenges that are difficult to overcome, including lack of trust, fear of change, exclusion, entrenched thinking, specialty silos, and endless meetings.

Lack of trust. Lack of trust in government is becoming more common in many communities, possibly born out of failed promises, poor interactions with government staff or processes, or the effects of dwindling budgets. Planners often have to rebuild or establish trust with community members to advance planning work.

Fear of change. Change, though inevitable, can be hard for people to accept. To many neighbors, growth means more housing units, more people, and more traffic, which can only erode their quality of life, strain already strapped city services, and threaten neighborhood architectural character, safety, and property values.

Exclusion. Planning processes have historically underrepresented groups such as minorities, low-income populations, and persons with disabilities, among others. Many planners and communities still struggle with removing barriers to participation for all.

Opposing views. People are becoming less willing to collaborate with countering viewpoints. Entrenched thinking, extreme polarization in partisan politics, and an increasing lack of civil dialogue are just a few of the many factors that make up this complex dynamic, and this can find its way into planning projects. Sometimes, even getting neighbors who disagree together in the same room is a challenge.

Specialty silos. Solving community planning problems requires collaboration between city agencies and interest groups. Specialty silos exist when people are so embedded in their area of expertise or advocacy that they have difficulty understanding and appreciating other relevant positions. Historically this has played out with transportation experts clashing with planners or environmentalists clashing with developers.

Endless, unproductive meetings. Collaboration on planning projects is a challenge because there is usually a large set of stakeholders with disparate viewpoints to engage. Efforts to involve everyone often results in meeting after meeting with slow progress, which can result in community fatigue and absenteeism rather than generating project support and momentum. Elected officials come and go during this time and group memory is lost, further slowing progress.

The NCI Charrette System employs a number of strategies for intervening in complex situations and moving groups from stagnation to action.

Begin by building trust and listening. The very first phase of the NCI Charrette System incorporates the idea of becoming "people ready." This involves an intense effort to identify and engage with all people who are key to a successful project — those whose lives will be affected by the outcome. Trust is built by first listening to their issues, needs, and values.

Embed people in the design process throughout the charrette. Charrettes use a collaborative design process to provide a new way for people to interact in community planning. During the multiple-day charrette, stakeholders engage in the evolution of the project design through a series of at least three review sessions or feedback loops, creating a flow of interchange between the design team and community members. Designers say that the three feedback loops "allow us to get it wrong twice." This process of the design team proposing, listening, and revising is an essential strategy for building community trust in the process. Understanding of and support for the design proposals develops as people see their feedback being addressed. When this is achieved, it is a step toward building trust between community members and with government.

Change perceptions and positions through collaboration by design. Charrettes engage people's creativity by visualizing change through the use of design sketches. This method expands the limits of the conversation beyond words and numbers. What might be described as an inquiry by design process helps people to engage in complex problems in a more complete way. Drawings allow a group of people to see the same idea clearly. For example, illustrating a setback line in a traditional zoning code and a build-to line in a form-based code allows community members to evaluate the walkability and sense of each resulting place. People begin to see that zoning decisions include many interrelated factors, including the relation of a building's form to its surroundings, parking requirements, and the realities of real estate markets, financing, and construction. People see how the data and regulations impact what they see and interact with in the built environment. Drawings also help people visualize a potential future, taking the fear out of the unknown.

Bring everyone together in one time and place to solve the problem. Bringing everyone together to solve the problem in a safe yet honest environment within a concise time frame can accelerate decision making. Misunderstanding or manipulation of facts is reduced when everyone hears the information at the same time. The pre-design phase of the NCI Charrette System focuses on identifying the key participants and ensuring their involvement. Charrettes compress months of meetings into a week or less. This approach is more successful in gaining the participation of key players whose attendance can normally wane after a few months of meetings.

Use a time-compression schedule that compels people to participate. Multiple-day charrettes have hard deadlines, such as the Thursday night public meeting where the design team is scheduled to present a preferred draft plan. These deadlines create a sense of urgency that "the train is leaving the station." As a result, key players like agency directors who may have been reluctant to participate suddenly show up more willing to negotiate. This again creates certainty and finality for moving forward. Additionally, the charrette schedule offers tens of hours of opportunities to participate, accommodating many different schedules.

Provide third-party facilitation without politics. Charrettes are usually facilitated by third parties that are impartial toward the outcomes of the charrette. This creates a safe environment in which to participate for all stakeholders and allows people to share their core values.

The NCI Charrette System

The National Charrette Institute (NCI) was a nonprofit organization based in Portland, Oregon, founded in 2001 to give charrette practitioners the knowledge and skills to help communities achieve transformation through the charrette process. In December 2016, NCI became a program within the School of Planning, Design and Construction at Michigan State University. It continues to be dedicated to transforming the way people work together by building capacity for collaboration by training others in its methodology, coaching and supporting others as they conduct charrettes, and conducting charrettes.

The NCI Charrette System is a process for collaborative problem-solving and decision making centered on a multiple-day charrette as the transformative design event. This system is a flexible three-phase framework that combines more than 20 process-based tools to ensure overall project success. It has three primary phases: pre-design, charrette, and plan implementation.

Phase One: Pre-Design Charrette Preparation

Whenever possible, the project-sponsoring agency should work with other participating departments, agencies, and key partners to create the project purpose, process, and scope. This assures that the project is well-informed and owned and supported by the key players. Projects that are conceived of and organized through a collaborative team approach will run more smoothly, thereby saving time and money.

In Phase One, which can last from one to nine months depending on the complexity of the project, the sponsoring agency, along with key partners and stakeholders, completes a series of assessment and organization exercises that begins with high-level guiding principles and ends with a detailed project process plan or roadmap.

This plan describes who will be involved and how, lists base data needed, and describes the charrette or co-design process and products. This information also provides a draft project scope and an estimated budget that can be used to write a request for proposals. A project start-up meeting creates a focused team approach to project management that will guide it through the inevitable hurdles that it faces on the way to approvals and implementation.

This phase is all about being "people ready," "data ready," and "place ready" for the design phase or charrette. Project success hinges on a properly executed charrette preparation phase. In particular, not having the right people involved in the early phases can be the major cause of "post-charrette meltdown."

Being People Ready

Being people ready starts with identifying those who must be involved in the charrette to assure a fully informed and supported project. These include:

- Decision makers

- Those historically absent from the public planning process

- People who will be directly affected by the outcome

- People who bring valuable information to the project

- Those who can promote the project

- Those who can block the project

Once stakeholders are identified, building their trust becomes an important and primary activity during the preparation phase. Typical strategies to build trust include steering committee creation, tours and audits, interviews, focus groups, and educational workshops. The key ingredient to building trust is building relationships that are authentic and transparent.

Being Data Ready

The hallmark of a charrette done well is that the outcome is often quickly implemented. For this to happen, it is crucial to have the necessary resources and data to ensure the final product is feasible. Also important to being data ready is securing the right expertise on the charrette team and making the data accessible to community members.

The base data that goes into the charrette process includes the results from any public interactions or engagements as well as any preexisting plans, reports, or studies. Common data categories include site, transportation, market, social/cultural, economic, regulatory, public health, environment, and urban design.

Being Place Ready

The heart of the charrette is the studio, home to the charrette team during the multi-day charrette. While it might seem the easiest piece to get ready, finding the appropriate location for the studio can often be a challenge. It must accommodate all the needs of a working design office as well as provide the venue for both small and large public meetings. One of the biggest challenges is to have full access to and use of the space for the entire length of the charrette.

Phase Two: Charrette

The charrette is the central design event of the NCI Charrette System. The use of this term is said to originate from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris during the 19th century, where it was used to describe the final, intense work effort expended by art and architecture students to meet a project deadline. The process began with the assignment of a design problem, or squisse, and ended "en charrette" when proctors circulated a cart, or charrette, to collect final drawings for jury critiques while students frantically put finishing touches on their work.

The charrette as applied to community design and planning combines this creative, intense time compression and peer critiques, still common in art and architecture schools today, with public workshops and open houses. The result is a co-design process capable of highly creative yet feasible solutions.

The charrette makes the best use of everyone's time by engaging people when their input will have the greatest impact. Contrary to a common misconception about charrettes, participants are not at the charrette all the time. Instead, they attend two or three feedback meetings at critical decision-making points during the charrette. These are interactive meetings during which community members engage in discussion surrounding the detail and trade-offs of alternative design concepts. In addition, the charrette studio is open to the public much of the time to accommodate people who cannot make the scheduled meetings. Charrettes typically provide in excess of 50 hours of open public time.

The charrette results in a feasible plan that requires minimal rework and is carried by the support of all stakeholders through implementation. This support is generated by the ability of the charrette to transform the conflict among stakeholders into collaboration and a shared vision and implementation plan.

A multidisciplinary charrette team consisting of consultants and sponsor staff is entrusted by the community to produce the plan. Stakeholders — anyone who can approve, provide valuable information, or promote or block the project, as well as anyone directly affected by the outcomes — are involved in the design process through a series of short feedback loops or meetings.

Feedback loops and meetings must be carefully timed to ensure that there are a variety of options to fit participants' varied schedules. While NCI advocates that charrettes last between four and seven days, the most important thing is to incorporate three feedback loops in the process (Figure 2). The more contention, groups, and people, the longer the charrette. For example, a seven-day charrette is typical for projects with a large geographic area or those that are highly political. A three-day "sprint" workshop is better suited for smaller and simpler projects. All versions accommodate the three feedback loops; the differences are in how the feedback loops are distributed. Processes lasting less than six days accomplish the first feedback loop between the project start-up and beginning of the charrette or sprint.

Figure 2. The NCI Co-Design Lexicon and the many ways to incorporate three feedback loops into a charrette process. Courtesy NCI & Farr Associates.

Phase Three: Plan Adoption and Implementation

The NCI Charrette System is designed to create the space and process for a set of agreements on a vision and how to achieve it. Projects that fail in the late stages usually do so when the charrette lacked the proper efforts to be people, data, and place ready. Ensuring this readiness prevents what might be called "post-charrette meltdown," which can occur after the charrette is completed and as the community is implementing the project. It can take the form of poor post-charrette communication with stakeholders; market, political, or regulatory changes that impact the agreements and project negatively; too much time to implement the project; opposition from people who were not properly involved in the process; and incorrect or missing data that exposes critical design flaws.

Despite the best efforts, planning projects can take years to implement. A well-run collaborative process can result in a feasible plan that is supported by the community for years to come. Because people were embedded in the design process, they understand the plan and have a stake in the outcome.

Considering the application of this system — preparation, the charrette, and implementation — through a case study brings it to life and demonstrates how the charrette system can defuse conflict and lead to positive outcomes. One such case study comes from Norman, Oklahoma, a college town where increasing demand for housing near the University of Oklahoma campus clashed with the preservation of neighborhood character.

Case Study: Norman, Oklahoma

In 2014, a developer in Norman, Oklahoma, proposed a five-story apartment building occupying an entire city block in a one-story single-family neighborhood. It had been more than 40 years since the last substantial update of Norman's zoning code, and though it was unclear how the proposed apartment building would fit into the existing zoning, nothing precluded it outright. The community was caught off guard by the proposal and how a building that was so out of scale with its surroundings could be permitted.

The Norman city planners held a series of public meetings aimed at establishing a vision for growth in the central city neighborhood, but they had a hard time moving the discussion beyond a debate on what the maximum allowable height should be. Neighbors were insistent on restricting development to two or three stories, while the city wanted to address the need for more housing by accommodating taller buildings. The conversation could not get beyond a battle over numbers of feet.

To overcome this impasse, the city decided to partner with the Institute for Quality Communities at the University of Oklahoma to try a fresh approach by engaging NCI to conduct a charrette. The Institute for Quality Communities was created by the university out of a commitment to improving the communities of Oklahoma. It saw this project as an opportunity to address the critical challenge of infill development right in its own backyard. The university and the city agreed to share the costs of the project.

Led by Norman's director of planning and community development, Susan Connors, AICP, NCI began by working with city staff from the planning and community development to scope the project: a robust public involvement process that would result in a vision and a new form-based code for the city center area, while rebuilding the trust of the community in the process.

The scope called for four areas of expertise: public involvement and charrette facilitation, urban design, form-based code writing, and transportation engineering. To accomplish this scope, NCI added Opticos Design (urban design), Alta Planning (transportation), and Ferrell Madden (code writing) to round out the project team. The city assembled an advisory steering committee representing the city, the university, developers, affected neighborhoods, the business community, planning activists, and neighborhood churches.

Phase One: Pre-Design

The strategy in Norman was to build trust well in advance of the charrette. To do that, NCI worked with the steering committee, held a walking tour, conducted extensive interviews with more than 80 people, and facilitated a public kick-off meeting during a two-day visit that occurred six weeks prior to the charrette. This work went a long way to build community support for the charrette and establish relationships with key stakeholders.

The interviews were conducted in accordance with the NCI process. City staff worked with the steering committee to create a list of people representing relevant viewpoints, including neighbors, developers, community advocates, and businesses. The interviews were held at a local church in three small meeting rooms. Staff received people in the lobby, and consultant members of the project management team ran the interviews. The interviewees did not attach names to the notes. Each set of interviews lasted 50 minutes, allowing the team a 10-minute break before the next group arrived.

These interviews achieved important goals. First, the interviewees appreciated the opportunity to provide their candid viewpoints about the project. They left more interested in being involved in the charrette. Second, the consultants gained a more complete picture of the political landscape of the project.

The most important pre-charrette event was the public kick-off meeting. While a large turnout was expected, NCI turned to the steering committee to communicate to its constituents the importance of attending the meeting. This, coupled with the communications in the interviews, assured a more well-rounded set of participants. During this meeting, community members completed a vision wall, a visual preference survey, and a strong places/weak places mapping exercise that helped draw out a community vision from participants.

Building on the knowledge gathered from the interviews and meetings, the NCI team created a set of draft project values, goals, and objectives to serve as a starting point for the charrette. Working off the project scope, the transportation engineer gathered existing traffic data for the area, the urban designers studied the form and character of the neighborhood, and the code writers discussed with the city planners how a new form-based code could work within the city code framework. The main goal was to assure that the charrette design team had all the information to complete the charrette deliverables.

The Norman project was fortunate to have access to a large meeting space run by a local community organization. Well known to the community as a neutral meeting space, this location proved to be a perfect location for the charrette studio.

Phase Two: Charrette

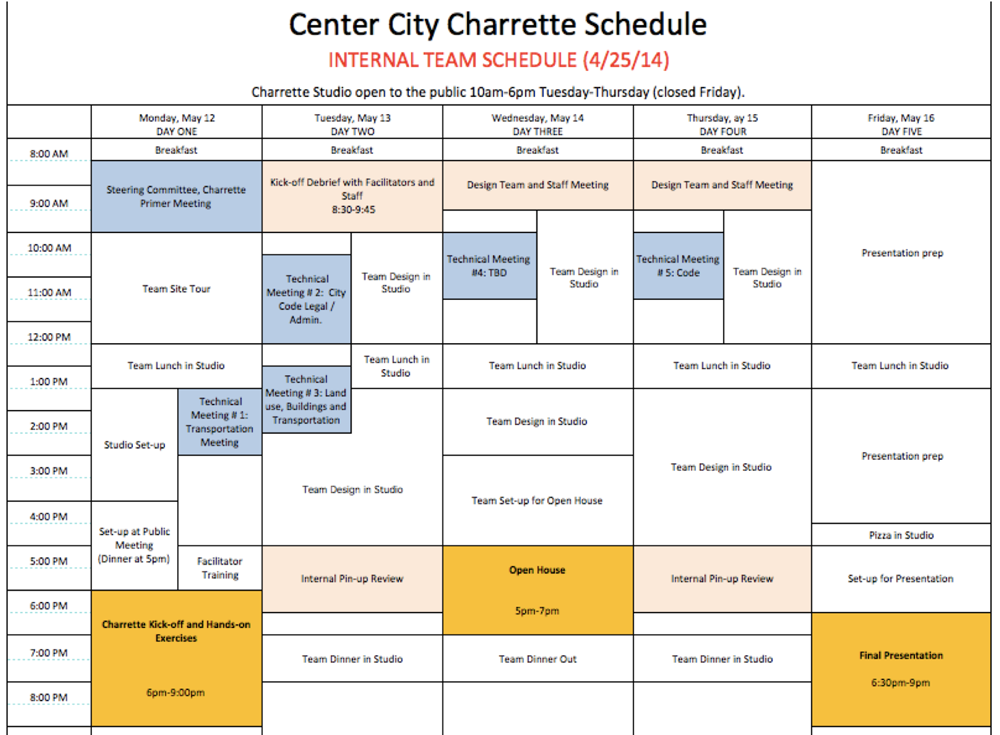

The five-day charrette followed the preparation phase and began on a Monday (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The charrette schedule to create a vision for Center City, Norman, Oklahoma. Courtesy NCI.

Day 1 (Monday) — Charrette Set-Up and Kick-Off

After setting up the studio and acclimating the design team, NCI opened the charrette with a public event to gather input on the public's vision. To get people busy when they step in the door, NCI employs an easy and effective method called a "sticky wall" to start a public meeting with energy and collaboration. In Norman, participants quickly built a set of the most common ideas for the future vision of the city center using sticky notes. NCI and Opticos then presented the project purpose and process, followed by a primer on neighborhood planning and form-based codes.

Working in small table groups, community members then began mapping vision ideas on aerial photos for the neighborhood. Each table briefly reported on the biggest areas of agreement, as well as any areas where they did not agree. NCI concluded the evening by inviting people to the midweek open house to see the designs that would be based on the evening's ideas, and reminded them of the times that the charrette studio was open for drop-in visits.

Days 2–3 (Tuesday and Wednesday) – Alternative Design Concepts and Open House

The following day, the charrette design team began developing alternative concepts for the city center area. Starting with a physical vision for the area and referencing collected community input and base data, designers began drawing plans and renderings that visualized ways that new buildings could be sensitively worked into the neighborhood. They also began to study the impacts of the envisioned growth on streets and parking.

Starting late Tuesday, a series of technical meetings were held with city staff to engage them in the design process on codes, land use, and traffic. These initial feedback sessions helped to keep the designs on a feasible course while making staff co-authors of the schemes.

Meanwhile, community members drifted in during open studio hours — a time when the charrette studio is open to the public while the charrette team is working — with staff conducting tours of the works in progress. People with a particular stake in the project, such as property owners, were able to meet one-on-one with designers, who walked them through the emerging alternatives.

This cycle of work continued until the open house on Wednesday evening, when the charrette design team put its pencils down and engaged with the public. Those concerned about traffic met with the transportation engineer, others interested in building form met with the architects. When it looked like there was a critical mass, the design team presented some of the key ideas and opened the floor to comments.

One of the most contentious issues concerned the design of the Campus Corner area, directly across from the university campus (Figure 4). This small commercial area with one- to two-story buildings is highly valued by the community. The pre-charrette interviews and meetings confirmed that the community was set on a maximum of two, maybe three stories for buildings in this area despite the fact that the existing zoning permitted more than three stories. There was also a desire that the plan would recognize subareas that could accommodate a range of uses and heights.

Early on in the charrette, the design team decided to test ideas for taller buildings that could accommodate retail and apartments. A rendering for a six-story building was posted for public review in the open house (Figure 5) and it was not well received; some people were upset that the designers would even consider such a scheme. Community input on this and other design alternatives was gathered through flip charts, sticky notes, sketches, and questionnaires.

Figure 4. Campus Corner current conditions. Courtesy NCI.

Figure 5. Campus Corner's first rendering showing a taller, modern building. © Opticos Design.

The design team convened that evening after the open house to review the alternative concepts in light of the input received from the technical meetings, the open studio visits, and the open house, as well as internal team reviews. The team developed a preferred alternative by merging the best ideas from the three alternatives presented.

Day 4 (Thursday) – Preferred Plan Development and Testing

Once settled on a preferred alternative plan, the design team developed more detailed investigations and testing of the plan. Ferrell Madden worked on the main elements of the code, building form and location, and parking allocations. The team met again with staff to further develop the main elements of the code. The transportation engineer developed proposed modifications to the neighborhood streets that would support a more walkable environment.

One of the team architects developed additional alternatives for Campus Corner. In contrast to the six-story building with a modern design that had been rejected, the architect proposed a southwest Mission-style building that referenced a historic building across the street. Early reactions from visitors to the studio toward this idea were positive.

As people continued to take advantage of open studio hours, staff gathered their ideas through sticky notes on drawings, flip chart notes, and questionnaires.

Day 5 (Friday) – Production and Presentation

The studio was closed to visits on Friday, allowing the charrette team to intensely focus on preparing the drawings and presentations for the closing meeting that evening.

The charrette team's final presentation recapping the week's work was attended by more than 150 community members. The bulk of the 45-minute presentation was devoted to the City Center draft preferred plan, which showed where and how different sizes and uses of building would be accommodated. The most important drawings were 3-D renderings that showed building form strategies for transitioning from higher-density areas into adjacent lower-density neighborhoods because they were approachable and easy for people to understand. Some of these drawings showed a bird's-eye view of entire portions of the neighborhood, while some hand-drawn watercolors of street-level views showed detailed building designs.

The presenters asked questions of the participants using instant keypad polling, which allowed everyone to vote on ideas anonymously. One of the most interesting polls came after showing the revised drawing for Campus Corner, in which 88 percent of participants voted favorably for the proposed five-story, Mediterranean-influenced building (Figure 6). This was a complete turnaround from the community sentiment against taller buildings before the charrette.

Figure 6. Campus Corner with stepped-back, five-story building, and three-lane Boyd Street with bike lanes. © Opticos Design.

Another controversial proposal was to return the one-way pair of streets running through downtown to a pair of two-way streets. The transportation planner presented this proposal and then another poll was administered. The result was 88 percent in favor of the proposal.

The last part of the presentation was a summary of the elements from the plan that would go in the next project phase, the writing of the form-based code. A final poll revealed that 62 percent believed that the proposals in the draft preferred plan were "on track."

Phase Three: Plan Adoption and Implementation

The Norman charrette provided the political momentum necessary to carry the code writing and adoption process to a successful conclusion. It did require several years and many meetings with the steering committee, but the new code for the City Center area was adopted in 2016.

Since then several new residential buildings have been erected in the project area, most of them two to three stories in height (Figure 7). The university's efforts to improve on-campus housing lowered the demand for off-campus student housing. The developer did not pursue the five-story building.

Figure 7. Duplexes built before (left) and after code adoption (right), showing increased density. Courtesy Susan Connors.

Action Steps for Planners: How to Know if a Community Is Charrette Ready

Besides being people ready, data ready, and place ready, there are other important factors to consider when deciding if a charrette is the right tool at the right time for your community, organization, or project.

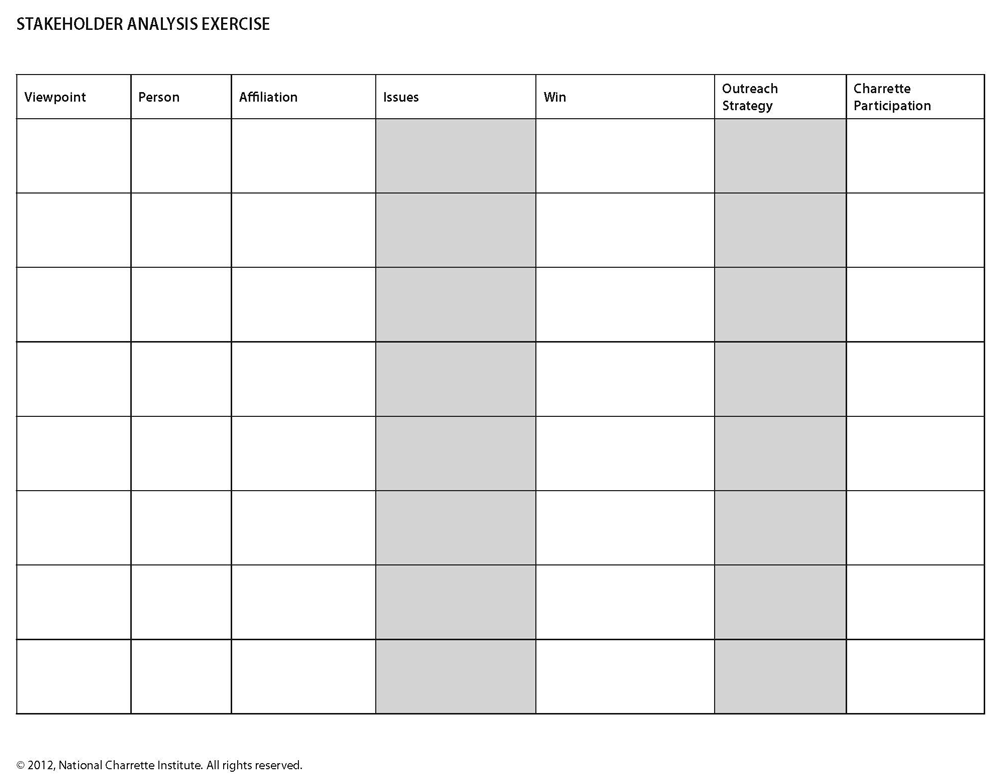

Is there the prerequisite level of trust for stakeholder participation? First, assessing the level of trust among the stakeholders is paramount. Consider also when the last public engagement occurred and what its impact on the stakeholders and the project was. Use a preliminary stakeholder analysis to make a quick assessment of the climate (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Planners can use a stakeholder analysis matrix to understand who should be engaged in a charrette and how. Courtesy NCI.

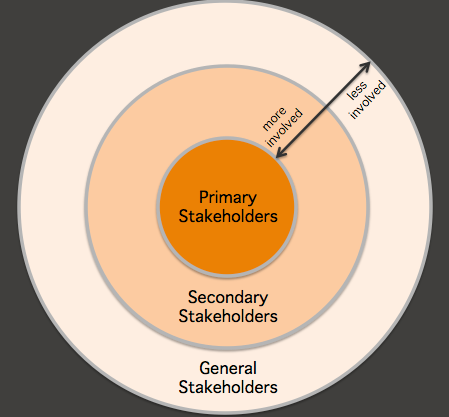

Planners must look at three levels of stakeholders in this regard: primary, secondary, and general (Figure 9). Primary stakeholders include public and appointed officials, while secondary stakeholders include nongovernmental organizations and businesses and residents directly affected by the project. General stakeholders include other citizens, including underrepresented populations.

Attendance from minority groups or low-income populations can present particular challenges for full engagement in processes such as charrettes. It may be necessary to involve a public involvement specialist early in the process. This person must have in-depth knowledge of the community and be able to connect with less visible leaders in the community that nonetheless will have an impact on project implementation.

Figure 9. Concentric circles illustrate the types of stakeholder involvement in a charrette, with engagement increasing towards the center. Courtesy NCI.

If after conducting a preliminary stakeholder analysis it is determined that important parties are not willing or able to participate, the timing may not be right. A key difference of charrettes as opposed to other public engagement processes is that participants are engaged in the co-creation of the proposal as opposed to simply reacting to a plan or proposal. Key stakeholders who are left out of the process will create difficulties for implementation down the road.

Is there enough lead time to prepare? An approach of "we'd like to have a charrette next month," without the necessary time for data collection, stakeholder involvement, or charrette team selection, is an unrealistic timeline. Successful charrettes may take six to nine months of preparation to have everything come together during the condensed multiday event.

Completing a quick "gut check" analysis on the complexity of the process is one way to gauge the timing and resources necessary to complete a successful charrette. For example, what is the quality of available market data? Will a new market study be required before the charrette? Important activities such as base data research and analysis, preliminary stakeholder outreach, and technical workshops should be conducted well in advance of the charrette. Making a working list of charrette products and responsibilities through a Gantt chart customized for the stages and activities of your charrette process will help guide the project start-up phase and help determine if enough preparation time has been planned.

Do we have the right resources? Taking stock of the resources available to you is important and will help give you an idea of the type of budget necessary for the project. The previous steps of considering stakeholders and complexity of the project are important for determining the types of resources needed for the charrette and its overall length.

Engaging stakeholders is time intensive, and if the project is complex you might need specialized talent. For example, does staff have time to organize and implement the public engagement meetings? If the project will involve technical aspects such as code writing or traffic engineering, is the time and talent available internally for these activities or will a consultant be necessary to complete the deliverable product? Similarly, there may be important regulatory, economic, or political elements that require additional skill sets and outside help to get the job done. Taking these and other factors into consideration will help you identify the resources needed to ensure a successful charrette process.

What to Do When You Are Not Ready

If the community is not yet ready for a charrette, there are still steps that can be taken to keep the process moving forward. For example, if it's determined that there is simply not enough trust among stakeholders to come together on important topics and the environment is contentious, a neutral facilitator or mediator may be brought in to help resolve underlying issues or concerns ahead of the charrette. In extreme cases such as pending or active lawsuits between stakeholders, a charrette may not be practical or advisable until certain disputes are resolved.

If a lack of outreach is a concern, conducting educational workshops on technical aspects of the anticipated project can help gain political momentum and understanding. For example, if the project involves new code work, as was the case in Norman, a workshop on form-based codes in advance of the charrette can educate residents on an important technical aspect of the project.

Because charrettes condense months of meetings into a week or less, filling gaps in knowledge of important and innovative planning terminology or practices may require extra outreach efforts. These educational efforts should involve both targeted geographic and demographic strategies. Messaging and content may need to be tailored to the specific audience that will participate in the future charrette.

Conclusion

At their best, charrettes provide collaboration by design by creating an environment of trust and transparency. Through a multiday event held on site and inclusive of all affected stakeholders, results can be achieved in a matter of days that otherwise would take months or years.

Development processes that are slow to materialize, lack authentic input, and never come to fruition can frustrate the public. By avoiding endless public meetings and breaking down specialty silos, charrettes can provide an important forum to embed people in a listening and design process with short feedback loops. The Norman, Oklahoma, case study provides an example of how the charrette process was used by a growing community faced with increased demand for housing while trying to maintain neighborhood character and rebuild trust in the community.

Working together to solve divisive issues and create successful projects is the "charrette way" for design-based public involvement that can change perceptions and positions and unleash local creativity.

About the Authors

Wayne Beyea, AICP, is a faculty member and senior specialist within the Michigan State University School of Planning, Design and Construction's Urban & Regional Planning Program. In this capacity, he maintains a teaching and MSU Extension outreach program with an emphasis on the science and policy of green community planning, renewable energy siting and infrastructure, and sustainable development and climate change law.

Bill Lennertz is the lead trainer of the NCI Charrette System, the first structured approach to design-based collaborative community planning. Since co-founding NCI in 2001, he has trained top staff from numerous organizations, including the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; the U.S. General Services Administration; the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; the departments of transportation in Oregon, New York, and Arizona; and many private planning firms across the country.

Holly Madill is the director of the National Charrette Institute at Michigan State University, where she conducts trainings and provides consultation and facilitation for charrette and other engagement processes. Having worked with the private, nonprofit, institutional, and public sectors, she specializes in community engagement, public policy, placemaking, and development of trainings, surveys and analyses, and strategy and policy documents.

References and Resources

Lennertz, William, and Aarin Lutzenhiser. 2014. The Charrette Handbook, 2nd Edition. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

National Charrette Institute. n.d. "NCI Charrette System."

———. 2018. "NCI Charrette RFP Template."

Norman (Oklahoma), City of. 2014. Norman City Center Vision Charrette Summary Report. July.

———. 2017. "Center City Form-Based Code." July.

———. 2017. "Norman City Center Vision."

PAS Memo is a bimonthly online publication of APA's Planning Advisory Service. James M. Drinan, JD, Chief Executive Officer; David Rouse, FAICP, Managing Director of Research and Advisory Services; Ann F. Dillemuth, AICP, Editor. Learn more at www.planning.org/pas.

©2018 American Planning Association. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without permission in writing from APA. PAS Memo (ISSN 2169-1908) is published by the American Planning Association, which has offices at 205 N. Michigan Ave., Suite 1200, Chicago, IL 60601-5927, and 1030 15th St. NW, Suite 750 West, Washington, DC 20005-1503; www.planning.org.