Work Programming

PAS Report 156

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 156 | March 1962 |

Work Programming

Download original report (pdf)

A work program is a coordinated series of related work projects which a planning agency intends to accomplish within a specific period of time. This period is usually one year, although longer periods are not uncommon. In essence, the program is a statement of the probable accomplishments of an agency. Whereas an annual report summarizes past performance, the work program is a systematic list of reports, projects, studies and plans that are scheduled for initiation or completion in the future.

Viewed in terms of over-all municipal administration, the work program is a part of the budgetary process. Before funds can be requested for operations, a department must be able to show the amount of work or service it will render, and the number of personnel and amount of money needed. From the viewpoint of the city's chief administrator, a lack of systematic work programming makes it difficult for him

...to know what services are being rendered for the expenditures made. It is impossible for him to evaluate the adequacy of those services, and it is impossible for him to properly justify, before the legislative body, the expenditure program which he recommends.

Work programming is the only logical and sound approach to the problem of preparing budget requests. It eliminates a large portion of the guessing from budgetary processes and it permits a more adequate evaluation of the need for proposed expenditures. Finally, by the use of work programs, responsibility for reductions in the chief administrator's recommended appropriations can be placed where it belongs — upon the legislative body.1

Whether or not the chief administrator requires the preparation of work programs, the alert planning director is interested in administering his planning program in such a manner that the agency's efforts bring the maximum quality and quantity of work product that it can provide with a given staff and budget. A work program can be a useful administrative tool to help accomplish this goal.

The principal advantages of work programming to the planning director are summarized as follows: The director must periodically consider the basic objectives of the agency. Past staff performance can be evaluated in terms of these objectives and alternate methods examined to achieve them in the future program. Since many more projects and studies have usually been suggested than can be done by the staff over a reasonable length of time, the director must cast aside those which do not contribute as much to the objectives of the planning program. In some planning agencies there are always a few planners who, because of long experience, can be given many different kinds of assignments. At the same time, less experienced staff members will not be given assignments that only a more experienced planner can accomplish. Consequently, the director must plan both the timing and work load so that some staff members are not overworked while others remain idle. In the large agency, many different projects will be going on at once with overlapping staff assignments and related objectives. Someone must coordinate the work of both individuals and teams so that duplication is avoided and gaps in the planning program are prevented. The work program can also be used as a tool in controlling the amount of staff time spent on various studies or plans.

While it is impossible to document, there is a popular notion that many planners are reluctant to admit that work on a study or project is finished. Often there may be a desire to gather more data, add refinements, or rework a report just one more time. There may be a point, however, beyond which additional work is not to the benefit of the planning department, The planning director should possess the technical judgment to make an objective decision as to when work should be brought to a conclusion. Staff members will be exhorted to produce — and produce on time — if the work program is well-known to them. Perhaps most important of all, a well thought out and administered work program may increase the director's systematic awareness of the workings of his department and enable him to exert more administrative leadership.

Basic Elements of Work Programming

Only a handful of planning agencies have had much experience with work programs. Consequently, the technique has not matured to the point that definite procedures can be outlined with a great certainty. However, some of the elements of the process and the related information needed for it are familiar from their application in the context of general municipal and business administration. Some techniques have been applied in planning offices with reasonable success; other techniques are completely inapplicable because of the nature of planning activity.

Some of the fundamental steps in preparing a work program include: examining the legal responsibilities of the planning agency, an assessment of past performance and future needs, a system of work measurement, setting agency objectives, and preparing the actual work program. These elements will be covered in varying detail in the remainder of this report.

OBJECTIVES AND FUNCTIONS

The planning director should set forth in a systematic manner the aims and purposes of his agency. The importance of objectives was stated in a witty hyperbolic manner by Daniel L. Kurshan in discussing his principles of "maladministration" at the 1958 ASPO Conference:2

Never Think in Terms of Objectives: They Are Bound to Change Anyhow. Determining objectives is troublesome. It may be that after thinking hard about it, we decide that we have no objectives, which may lead to speculation as to what we are doing around here anyhow. This could be very depressing. It's a great deal easier to plow right into whatever problem we have before us without worrying about what our underlying responsibility may be and whether that responsibility ties in with our authority under the law and program established by top management. This helps our ego and makes us think we're "doers" and cuts through the red tape of organization and orderliness.

Further, by taking the bull by the horns and proceeding "full speed ahead" without reference to objectives, we tend to offset any unfavorable impressions that might be created in the minds of the public that we think ahead and that we may be "planners" (i.e., socialists, or at best, eggheads). Our profession has yet to shake itself loose of the stigma of such an aspersion.

Another advantage in avoiding the unpleasant subject of objectives is that by so doing we can neatly side-step the question of whether we are meeting our objectives. Obviously if nobody knows what we are supposed to do there is no way for them to tell whether we are doing it. To a business administrator this is the equivalent to having the income tax bureau tell us we need no longer file returns — and that we'll be taxable only if we get into a row with someone. It's a Magna Charta!

Most successful administrators have little difficulty in avoiding the danger of formulating objectives. They are usually so busy on their day-to-day activities that they have no time to think ahead and decide where they are going. This, of course, is as it should be. So, for most of us, observing principle number one comes naturally and should cause no pain.

Legislation and Objectives

Although it may seem elementary, the first place to begin in determining objectives is the legislation that either creates the planning agency, or allows it to operate. For example, the state enabling legislation that created the Northeastern Illinois Metropolitan Area Planning Commission states the functions of the commission in very broad terms, yet at the same time outlines some of the activities that the legislators expect will be done. The statutes provide for the continuing program of the agency to include seven major functions:

- Provide for the active participation of all local governmental units and other public and private authorities in a review of the needs, requirements, and goals from the metropolitan point of view.

- Conduct research and surveys of the conditions, trends and future prospects of the economic, social, physical and governmental development and needs of the metropolitan area.

- Prepare and keep up-to-date a long-range comprehensive plan of major features that provide for the best practical future development of the metropolitan area in terms of its needs, requirements, and goals.

- Assist local planning agencies by providing information on matters of regional significance that affect local planning.

- Provide technical planning assistance to local units of government.

- Encourage cooperation among local governmental units and regional authorities to coordinate their plans with other local and regional units and to solve problems that overlap municipal boundaries.

- Establish a continuing program of public information to create awareness among the people of the metropolitan area of their common interest in the sound development of the area as a whole.

The importance of both the responsibilities and constraints contained in the enabling legislation concerning the work program is illustrated by the following remarks:3

Since it [the planning commission] is regional and operates in Ohio, certain conditions pertain which might not in other states or under other organizational setups. For example, this office is entrusted, under law, with the problem of .preparing plans and maps "showing the commission's recommendations for systems of transportation, highways, parks and recreational facilities, the water supply, sewerage and sewage disposal, garbage disposal, civic centers and other public improvements which affect the development of the region or county respectively as a whole or as more than one political unit within the region or county and which do not begin and terminate within the boundaries of any single municipal corporation (Ohio Revised Code, Sec. 4366-15)."

In addition, the Ohio law permits regional planning commissions to contract with the federal government or state and local government on planning matters. Additional responsibilities are given regional planning commissions in that they act in an advisory capacity and must make recommendations to the local townships on zoning matters (including individual zoning changes). Finally, regional planning commissions act as the administrator of subdivision regulations where such power has been delegated to it by the plat-approving authorities of the municipality or county. At the present time, this office is acting as an administrative body in this regard for the unincorporated areas of the county and in an advisory capacity to several of its member communities.

The work load of any planning agency is significantly influenced by statutory provisions. These provisions determine the size of the administrative load caused by mandatory or voluntary administration of either zoning or subdivision, ordinances. Obviously, the relative flexibility of this administration will depend upon time limits within which recommendations or actions must be taken. The work program will also be influenced by provisions that deal with mandatory referral or capital improvement programming. In addition, if the planning agency is to engage in various planning projects supported by federal funds, time limits and deadlines (as well as specific project programming) will have to be rigorously adhered to. Finally, the work program is influenced by the number of governmental units that have a voice in determining both specific projects and priorities among them. Agreement is probably more easily attainable with only one mayor and city council than with a dozen as may be the case in regional planning agencies.

PAST PERFORMANCE AND FUTURE GOALS

Every planning agency should periodically take a long critical look at where it has been and where it is going — what it has done and what it yet needs to do. This kind of analysis is often done by an agency with a new staff, an agency that has just had its budget and staff significantly increased, an agency that is arguing for such increases, or an agency that one day finds that it has been doing very little planning. This kind of soul-searching may sometimes accompany a change in the political leadership of the local government or the appointment of a new planning director. Unfortunately, it is not done often enough by the average planning agency. The director may spend his idle moments "thinking" about changes that should be made, or changes that will be made "someday." Too often this thinking is done unsystematically and never put on paper or discussed with the chairman or members of the planning commission.

Such an analysis of the past program of the planning agency should be formal enough to produce a working paper for planning commissioners and interested public officials. This method should have great educational value because the programs of the agency would be discussed both individually and in their relationships with one another. The commissioners will learn some details (such as background information, required field work and methodology) about the various kinds of studies that are undertaken in a planning program. They will also learn that a report of only a few pages or a single map may represent months of work by a number of staff members. Gaining more knowledge about the work of the staff should also emphasize the fact that some kinds of studies must be used immediately if they are not to become outdated, while other studies must be repeated or brought up to date periodically. By discussing the planning program as a whole, as well as its various components, the elusive concept of the "planning process" may become more meaningful.

While no ready answer can be given to the question of what should be investigated in such a review of the planning agency's work, a broad framework with some examples may be helpful. Some of the factors will, of course, be considered by the alert planning director every time he reviews a single year's program.

One of the first steps would be to review all the work of the planning agency since its inception (a vast number of planning agencies are no more than a decade old) or, if the agency has been in existence for some time, since the end of World War II, perhaps. In the latter instance, it might be interesting to note what the agency had said it would do, and compare this with what was eventually done. If there has been a wide discrepancy, it may be cause for concern. Asking "What have we done for the past ten years?" may reveal that the agency has been primarily an administrative one. Or, it may have turned out reams of reports without any concrete implementation. The agency may have vowed to keep updating its comprehensive plan (new ten years ago), but has not been doing so. A major shift in emphasis of the work program of an established agency may also be necessary when a new planning agency is formed in the same metropolitan area. Seeking cooperation and avoiding duplication of work and services may require close cooperation in working out mutually beneficial work programs.

Individual plans and study areas must be examined closely. The school plan may be in the process of being implemented because estimates of original building needs were not accurate. The major streets plan, finished only eighteen months ago, may need substantial revision because the state has abruptly changed its previous highway plans. Certain studies which required specialized personnel may now be done because the agency has the trained manpower. Long-range work plans must be made if a complete revision of the community's plan is contemplated in the near future, or if a major project, such as a comprehensive revision of the zoning ordinance, is to be undertaken.

If a complete, objective study of the work program and general administrative practices is necessary, an outside consultant can be retained. For example, in 1956 the Los Angeles City Planning Department hired a consultant to examine the administration of its planning program. The consultant examined the agency's work since 1941, and gave specific attention to each element of the planning program.4 An evaluation of the progress within each area of study and recommendations for improvements also were made. Not only was the agency reminded of shortcomings in the drafting of certain plans, but suggestions were given for improving certain procedures in zoning and subdivision regulations to make more efficient use of staff time. After an analysis of past work and achievements, recommendations as to the direction and nature of the future work program were offered.

Whether a basic review of a planning agency's work is done by an outside consultant or by the agency itself, the problem is to compare one's own planning program with "good practice." There is no authority for what constitutes good practice, but there are some areas of agreement. For example, ASPO Planning Advisory Service Information Report No. 107, Check Lists for Planning Operations, February 1958, describes the use of a number of check lists for improving the end products of a planning agency as well the impact of these end products on the administration of the agency. Such questions are raised as: how much time is wasted by both the planning staff and public officials because provisions of the zoning ordinance are vague and result in an endless number of appeals that must be processed? Are subdivision review procedures such that the minimum amount of staff time is expended while good planning principles are meantime observed? Other items on the check list emphasize elements of the planning program, such as public information efforts, by which the agency can measure its accomplishments and decide the relative importance of various kinds of activities within its staff and budget limitations.

Although most planning directors often know the shortcomings of their programs, the check list can be a useful tool to measure accomplishments in a systematic manner. By using the list to compare proposed programs and activities, a start can be made in assigning priorities among various projects. Also, the director can refer to the list periodically to note improvements that have taken place.

Many factors will influence both the elements and timing of the work program. Some are of an intangible nature, but nevertheless must be considered. The most important of such factors concerns the staff of the agency. The basic question involved is: how many men, with what abilities and experience, and at what salaries, are needed to do what specific assignments? A planning director with a number of open positions may have to guess whether they will be filled during the program period, and whether the personnel filling them will have the capabilities originally envisioned. The amount of work that will be done by the staff, in contrast to the amount that might be done by consultants either independently or in cooperation with the regular staff, would be considered as well as the size of the agency's budget for special studies or extra and temporary personnel. Naturally, the agency must be organized in such a way that responsibilities and assignments are clearly understood (see ASPO Planning Advisory Service Information Report No. 146, Principles of Organization for Planning Agencies, May 1961).

The work program will also be influenced by the depth of planning analysis that is necessary or desirable. Obviously, the large city will probably spend more for an economic study than a small city. Two cities of the same size may also spend different amounts, because of the amount of detailed information desired for plan preparation. If the agency's goal is to prepare an area-wide sketch plan so as to achieve an immediate impact on development decisions, its program would be considerably different than that of an agency in a city with a long history of comprehensive planning. Community acceptance of particular kinds of programs will also affect the work program. For example, one major city launched a vigorous urban renewal program that was "ahead" of concurrent planning activities (action cannot always await the plodding planner) because public officials judged that the time for public acceptance and support was then ripe. In another city a few years ago, the planning staff was faced with a choice (because of rigid budget limitations) between a general central business district study and an intensive parking study. It was decided that community and business leadership was not ready for bold proposals which might come from a more general study, and that an intensive look for a solution to a pressing visible problem — parking — would ensure full support for broader planning programs in the future.

The work program must also take into account the ongoing activities and policies of the agency. Staff time in the metropolitan agency may be taken up by frequent attendance at planning commission and city council meetings in numerous localities. Another agency may devote considerable time to a publications program, citizen participation activities, or other relatively intangible activities.

WORK MEASUREMENT

Public administrators and students of government have been trying for years to find satisfactory methods of measuring the performance of various municipal activities. Every administrator often asks himself "How well are we doing?" This is often a difficult question to answer. It can be particularly difficult for the planning director.

In terms of general municipal administration, there are three important questions that are recognized: What can be measured? Why should it be measured? How should it be measured? The range of activities that can be measured is wide, as shown by the following:5

- Measurement of needs for

- Capital improvements

- New or increased current programs

- Ability of the tax base to support a certain level of expenditure

- Adequacy of program, with need as a standard (sometimes stated as "potential effectiveness")

- Performance of

- An individual

- A piece of equipment

- A team or group

- An entire project, or activity

- Measurement of "input" (expressed as man-hours or equipment hours, or as dollar costs)

- Measurement of results (which are concomitants of performance)

- Effectiveness in

- Performance, as compared with standard performance

- Execution of a program, with the work program as a standard

- Attainment of goals, with program objectives as the standard

- Efficiency

- "Output" compared with "input" and the resultant laid against a standard cost (in dollars or effort)

Many kinds of activities of local government, such as police and fire protection, can be measured reasonably well for administrative purposes. Unfortunately, the planning director who is interested in accurate measurement is faced with the problem that the work of the city planner, unlike that of many other municipal agency personnel, cannot be precisely measured. The basic task is finding a standard unit end product which is measurable. The remainder of this section of the report is a description of various techniques that have been tried in planning offices with some degree of success. The reader should bear in mind that the methods are still largely new, tentative and exploratory.

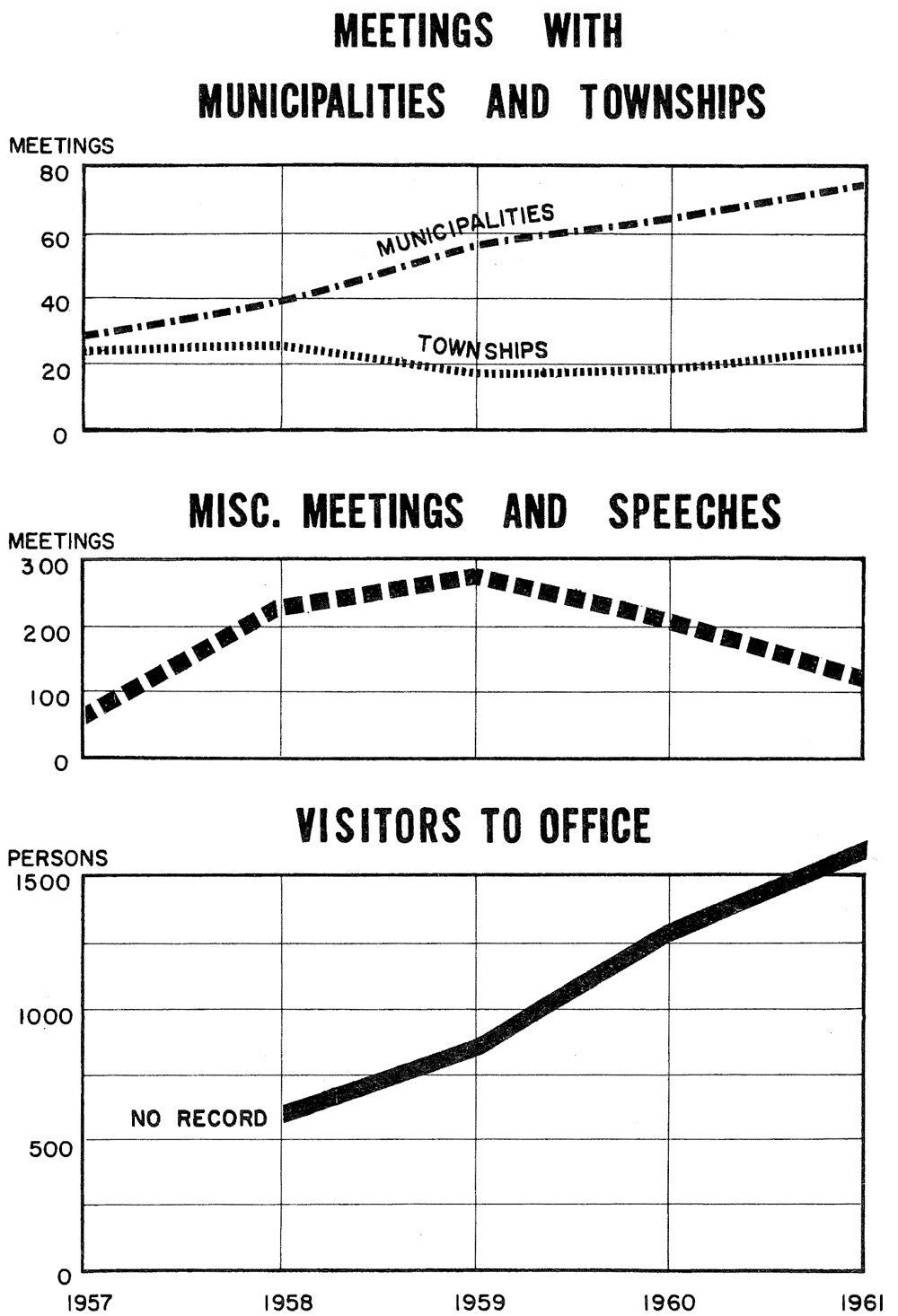

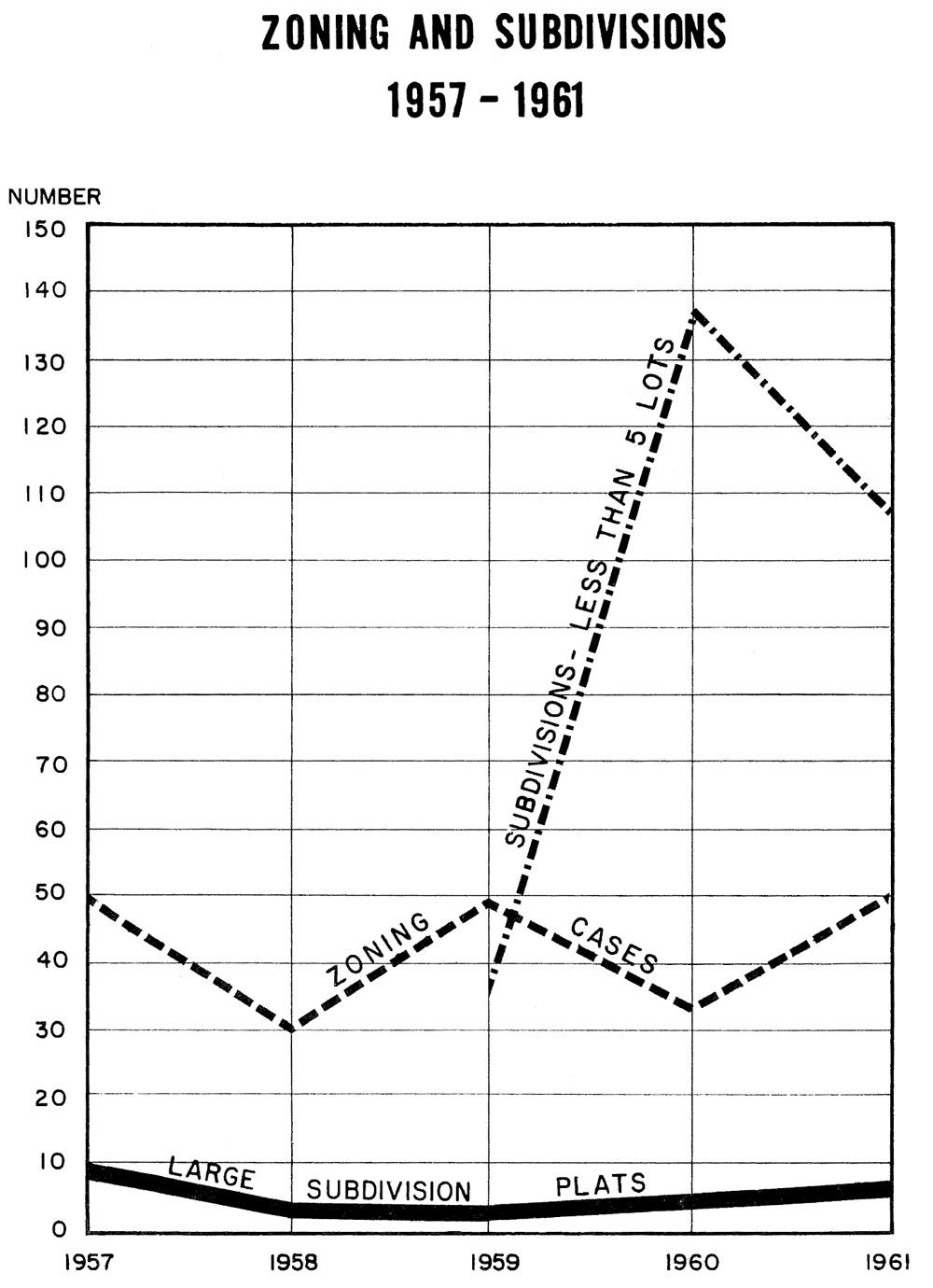

There are a few aspects of a planning agency's work that are relatively easy to measure. Zoning and subdivision cases, mandatory referrals, meetings with officials and citizens, office visitors, correspondence, street openings and closings, public hearings, speeches, and perhaps a few other less common activities can be measured. Very often there is no extra work involved in using statistics about these aspects of the work load since many planning departments keep this kind of information as a matter of course to keep track of development trends by recording subdivision activity and for the preparation of annual reports. The importance of keeping this type of record for work programming is that implications about future work load can be inferred from the data. This is not to say that the agency should use statistical formulas, but rather that simple graphs can be quite useful. For example, Figures 1 and 2 show some records of a regional planning commission for a period of five years and indicate the course of a part of the agency's work. Staff time devoted to meetings with municipalities (Figure 1) showed a steady increase for the five-year period, indicating the increase in local planning assistance. Meetings with township officials remained somewhat steady during the period. Meanwhile, the number of miscellaneous meetings rose and then began to decline, showing to some extent that the goal of building acceptance of planning in the region was being achieved. When the trend for both municipal and miscellaneous meetings are compared, it is seen that staff time was being spent more on work sessions concerning local problems. The figure also shows that the number of office visitors is continually increasing. Obviously, this means that more staff time is being devoted to handling everyday business of the public. The number of zoning and large subdivision cases (Figure 2) vary from year to year but still remain within certain broad limits. The large increase, then subsequent decrease in small subdivision review, is due to the fact that while the regional planning commission at first assumed this responsibility, it was later taken up by a few municipalities that began to exercise extraterritorial jurisdiction.

Figure 1. Reproduced from the 1961 Annual Report of the Lorain County (Ohio) Regional Planning Commission

Figure 2. Reproduced from the 1961 Annual Report of the Lorain County (Ohio) Regional Planning Commission

These planning staff activities can be easily measured primarily because there is a definite unit of measurement, and because each activity is recurring. If all the work on these activities is always done by the same staff members, costs can readily be computed. Often, however, other staff members are assigned to administrative work during crisis periods and these costs are subsequently forgotten if no other work records are kept. Moreover, other kinds of planning work are neither recurring nor easily measured by a simple unit. A number of cases in which planning agencies are attempting to measure all staff work follow:

Franklin County, Ohio

A time-recording system that appears relatively easy to administer is used in the Franklin County (Ohio) Regional Planning Commission.6 The system was initiated because of the necessity to record the time and expenditure for the three basic parts of the agency's program: regional planning for which each participating community pays a per capita fee; county administrative responsibility with the county paying specific administrative costs; and, contracts (both direct and federally assisted) with local communities for planning assistance. The system has been in operation for three years and is used to analyze all aspects of office operations, as well as estimating the cost of future projects and planning activity.

Each project or activity is given a number as shown in Appendix A. The four major categories are regional, county, local assistance, and general administration. Within each broad grouping, numbers run consecutively from 01 through 14, and 80 through 84. The lower numbers refer to specific projects, some of which have been completed or just initiated. As new projects are undertaken, the numbers will be used up to 79, after which new projects will be assigned to numbers that are no longer being used. Where necessary for financial recordkeeping, certain projects are further broken down with an additional letter designation: A – nonchargeable; B – chargeable to direct contract; C – chargeable to 701 contract. The numbers in the 80's refer to regionally related activities and are continuing activities of the commission. Where appropriate, similar numbers have been used for county, local assistance and general administration.

Time slips, as shown in Figure 3, are made out by individual staff members. The smallest unit of time recorded is one-quarter of an hour. All staff activity is recorded under one of the categories occurring under either county, regional, local assistance, or administration. The number of hours of each person and category are totalled at the end of each month. The time computed in hours is multiplied by the staff member's hourly rate including a factor for overhead, to obtain the total cost of staff time. The number of hours is totalled for each major group and for each specific category within it.

Figure 3. Time slip

The combined cost of county planning, regional planning, local assistance, and general administration thus equals the number of dollars spent each month, including overhead. An accumulative total is kept for each group and specific category by month throughout the year. Consequently, totals of staff time and actual costs are available at any time.

The system has been revised, refined and expanded but it remains one that is relatively easy to use. Although there is occasionally a feeling that the system is too detailed and too much of a nuisance, the agency has derived considerable value from it. Even if the commission were not involved in separately financed programs, the system would still be valuable for programming and administration.

Lexington, Kentucky

A more complex system of work measurement is used in the City-County Planning Commission in Lexington, Kentucky. The purpose of the time-cost recording system is to "provide a factual record which will enable the Director, the Planning Commission, City and County government, and other interested agencies or persons to become better informed as to what it costs, in time and money to carry out different work phases of our comprehensive planning program."7

The mechanics of the system can best be explained in terms of the forms that comprise the system. The forms describe different work projects, means of calculating time and money spent on each project, methods of accumulating time and cost values at various time intervals for individual staff members and for the staff as a whole. In all, there are twelve forms:

- Work classification list

- Percentage of day's time list

- Percentage of month's time list

- Portion of month's cost list

- Daily appointment record

- Individual monthly record

- Individual yearly record

- Staff monthly record

- Staff yearly record, by individual

- Staff yearly record, by month

- Staff yearly record, by cumulative month

- Monthly and yearly report to Planning Commission

At first glance, this list looks formidable; however, on closer examination, the system does display a logical order.

The work classification list is a listing of each type of work project or assignment that can be undertaken by a staff member. The full workday must be accounted for by each staff member through the listing of a specific project. Projects are broken down by one-, two-, three- and four-digit designations. Although summaries of staff work are presented, usually in one- and two-digit breakdowns, each staff member tries to be as specific as possible in listing an assignment.

The one- and two-digit breakdown is as follows (a detailed breakdown is presented in Appendix B):

| Account No. | Work Breakdown |

|---|---|

| 1000 | OFFICE OF DIRECTOR |

| 1100 | Community Information Operations |

| 1200 | U.S. Federal Operations |

| 1300 | State of Kentucky Operations |

| 1400 | Lexington and Fayette Co. Operations |

| 1500 | Planning Commission Operations |

| 1600 | Staff Operations, General |

| 1700 | Staff Operations, Fiscal and Property Control |

| 1800 | Staff Operations, Housekeeping |

| 1900 | Staff Operations, Work Program |

| 2000 | Professional Organizations |

| 3000 | PLANNING SERVICES DIVISION |

| 3100 | Division Operations |

| 3200 | Current Planning Section |

| 3300 | Subdivision Regulations Section |

| 3400 | Zoning Ordinance Amendment Section |

| 3500 | Zoning Ordinance Appeal Section |

| 5000 | ADVANCE PLANNING DIVISION |

| 5100 | Division Operations |

| 5200 | Research and Analysis |

| 5300 | Preliminary Plan Formulation |

| 5400 | Preliminary Plan Testing |

| 5500 | Final Plan Proposals |

| 5600 | Implementation Devices |

The detailed breakdown in Appendix B shows how staff time can be tabulated. For some planning offices, the summary breakdown shown above would be sufficient. The degree of detail must be compared to the degree of complexity in administering the system. In addition, the information that is gathered must be useful. Thus, a planning agency may start with a three-digit system, then later cut back to a two-digit system if the data were not being used to good advantage.

Although many subject categories may be similar from one agency to another, there will be variations depending upon the type of agency and the specific aspects of the planning operation that a director wanted to measure. One director may be especially interested in the time and staff required for numerous short projects. Another may be more interested in which phases of the planning process his agency is concentrating on. Nevertheless, the object of any system should be the gathering of information that will enable better work programming and provide a better understanding of the agency's work.

The next three forms in the record-keeping system are used only by the individual staff member. On Form 2, workday percentages are computed. Because the workday is eight hours, no time period smaller than one-half hour is recorded, and all percentages are recorded to the nearest 5 per cent. The form thus is a valuable time-saver to the staff member, while lessening the chance of errors. Form 3 is analogous to Form 2, but it is on a monthly basis. Form 4 brings together both the time and cost factors to permit the individual staff member to find the cost of his time on a particular project. It should be emphasized that Forms 1 through 4 are only used when the individual fills out his timekeeping records.

Form 5 is optional and only used by the staff member if he finds it helpful in keeping a detailed account of a day's time. Thus, if he spends the entire day on one or two projects, he records the proportion of time on Form 6, the monthly record. At the end of each month, he simply transfers the totals to Form 7, the yearly record which he also keeps himself. In all cases, the figures used are either percentages or sums of money — never the number of hours or days.

Forms 8 through 11, kept by the secretary-office manager, are summaries of the individual staff records. Thus, the planning director has an up-to-date account of staff time spent for the current month, each cumulative month, and the year as a whole, with the respective costs. Form 12 is a yearly time and cost summary which is presented to the planning commission.

The Lexington system is the most complex to be considered in this report. Although it does appear that the system takes time to administer, most of this work is done by nonprofessional staff. The staff planner has much of the mechanics of the system already worked out for him. For those agencies interested in trying such a system, the records will provide extremely detailed time and cost information on a current basis for individuals and staff.

Cincinnati

A particularly useful cost-recording system has been employed by the Cincinnati City Planning Commission for a little more than two years. The purpose of recording staff time on all planning projects "is to provide a factual record of the time and cost of the planning work in sufficient detail so that the Director, the Commission, the Council, and all interested persons can be better informed on what it costs, in time and money, to do the planning job. With better information, better estimates can be made of future work; which will help in determining the staff necessary, the time to allow, and the budget needed to do the job."9

The system separates various characteristics of the staff's work into different categories. For each planning project, four types of information are obtained: division assignment, project title, subject emphasis, and phase emphasis. Originally there was also a geographic area category, but this was later dropped because all the staff's work was within the city. A metropolitan or regional planning agency may find a geographic classification of its work quite valuable, however. Categories are identified by a two- and three-digit code system. The system originally employed electronic data processing equipment. However, its use produced an unmanageably large amount of detailed information which was not necessary for the purposes of the time-cost recording program. In addition, data were not made available until long after they were needed because the planning commission's administrative data processing received a low priority at the city's data processing center. The system has since been simplified and processing is now done manually by the planning staff.

The information needed from each staff member is:

- Project Time and Cost

- Total for each project

- by professional staff

- by nonprofessional staff

- Total for each project

- Phases Time and Cost

- Total of each phase

- Major phases for each project

Each person (professional and nonprofessional) in the planning office records his time by hours, in no less than two-hour periods, for each separate project and phase. Information is recorded on time sheets designed so that code numbers are inserted in a column entitled "Project," and hours are recorded in a column entitled "Week." Each staff member totals his own time for each separate project. A member of the administrative staff computes costs and totals the time and costs for each project in a quarterly report.10

The broad categories of information and the code numbers that are recorded are (detailed breakdown appears in Appendix C):

| Division | |

|---|---|

| 01 | Administration |

| 02 | Advance Planning (City and Metropolitan Scope) |

| 03 | Planning Services (Zoning, Subdivisions, Referrals) |

| 04 | Urban Renewal (Any Scope) |

| 05 | Advance Planning (Local Project Scope) |

| Project Title | |

| Numbers consecutively as they occur | |

| Subject Emphasis | |

| 10 | Circulation |

| 20 | Utilities |

| 30 | Land Use |

| 40 | Sociology and Culture |

| 50 | Economics |

| 60 | Physiography |

| 70 | Legislation and Government |

| Phase Emphasis | |

| 10 | Research and Analysis |

| 20 | Idea Formation |

| 30 | Idea Testing |

| 40 | Proposals |

| 50 | Implementation |

| 60 | Nonproductive Time |

The numbers assigned to a project occur in the following sequence: Division, Title, Subject, Phase. Using the Red Bank-Corsica urban renewal project as an example, the work would begin with research. The number assigned to the project would be the next available in the Urban Renewal (04) Division, in this case 04-010. Because the general subject was land use, the next digits would be -30; because the first phase was research, the last digits would be -10.

The project, at this point, would be identified as 04-010-30-10. As work progressed to other stages, the last two groups of digits would change but the first two would always remain the same. When working on streets, the subject would be -10. When drafting the final report, the phase would be -40.

Tables 1 through 4 are a comparison of the relative amounts of time and money that have been spent by each division, and by the staff as a whole for each phase of the planning program. These tables demonstrate that a smaller proportion of time was spent on idea formulation and idea testing in 1961, while more time was devoted to preparing actual proposals. The tables also show the difference in phase emphasis at different periods. For example, 50 per cent of the time spent on the Queen City Freeway Project in 1960 was devoted to research. In 1961, this proportion was only 11 per cent. Even more striking is the record on the New Zoning Ordinance, which showed no time on proposals in 1960 and 49 per cent of staff time on proposals in 1961, because the staff was then drafting the proposals that were intended to be submitted by the end of the year. The manner in which this kind of information was used in drafting Cincinnati's 1962 planning work program will be more fully discussed in a later section. A graphic presentation of past and future programs appears as the centerpiece of this report.

Table 1. Hours and Costs of Phases of Planning Process, Total Office, 1960 and 1961

| Phase | Code | 1960 | 1961 | ||

| Hours | Cost | Hours | Cost | ||

| Research | 10 | 9,034 | $23,747 | $11,390 | $33,550 |

| Idea Formulation | 20 | 14,718 | 42,942 | 14,321 | 45,310 |

| Idea Testing | 30 | 3,755 | 12,553 | 1,928, | 7,072 |

| Proposals | 40 | 5,188 | 14,569 | 11,391 | 34,513 |

| Implementation | 50 | 753 | 2,891 | 1,983 | 6,544 |

| Total | 33,448 | * | 41,013 | * | |

*These costs are not summed because they do not represent the total cost of personnel in the office. Some parts of the daily workload do not lend themselves to phasing, particularly those of an administrative nature.

Source: Cincinnati City Planning Commission, 1962.

Table 2. Per Cent of Time Devoted to Different Phases Of Planning Process, Total Office, 1960 and 1961

| Phase | Code | 1960 | 1961 |

| % Time | % Time | ||

| Research | 10 | 27% | 27.5% |

| Idea Formulation | 20 | 44% | 35% |

| Idea Testing | 30 | 11% | 5% |

| Proposals | 40 | 16% | 27.5% |

| Implementation | 50 | 2% | 5% |

| 100% | 100% |

Source: Cincinnati City Planning Commission, 1962.

Table 3. Hours and Per Cent of Time Devoted to Different Phases of Two Projects Continued from 1960 into 1961

| Queen City Freeway | New Zoning Ordinance | ||||||||

| 1960 | 1961 | 1960 | 1961 | ||||||

| Hours | % | Hours | % | Hours | % | Hours | % | ||

| Research | 10 | 1,567 | 50 | 192 | 11 | 465 | 21 | 180 | 3 |

| Idea Formulation | 20 | 1,137 | 36 | 917 | 53 | 812 | 38 | 1,810 | 38 |

| Idea Testing | 30 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 887 | 1 | 456 | 10 |

| Proposals | 40 | 428 | 13 | 616 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 2,352 | 49 |

| Implementation | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 3,144 | 100 | 1,725 | 100 | 2,164 | 100 | 4,798 | 100 | |

Source: Cincinnati City Planning Commission, 1962.

Table 4. Distribution of Total Man-Hours, 1961 (Projects Completed or Carried Over)

| Projects Completed in 1961 | 5,083 | |

|

Advance Planning and Urban Renewal |

5,083 | |

|

Planning Services |

0 | |

|

Administration |

0 | |

| Projects Carried Over to 1962 | 60,570 | |

|

Advance Planning and Urban Renewal |

33,469 | |

|

Planning Services |

14,447 | |

|

Administration |

12,654 | |

| Non-Productive Time (Holiday, sick, vacation) | 6,345 | |

|

01 Division |

724 | |

|

02 Division |

2,784 | |

|

03 Division |

1,547 | |

|

04 Division |

1,290 | |

| Total Man-Hours | 71,998 | 71,998 |

Source: Cincinnati City Planning Commission, 1962.

PREPARING THE WORK PROGRAM

Kurshan, who previously admonished planners to never think in terms of objectives, goes on to say that planners should:11

Plan No Programs. Some planners who are otherwise successful practitioners, having neatly side-stepped the preparation of objectives, fall into the trap of drawing up programs. This almost negates the value of having failed to establish objectives because a well-defined set of programs can be construed to add up to the implementation of objectives with all the accompanying dangers of having established objectives. This is almost too horrifying to contemplate.

Furthermore, once we get work programs down on paper it is almost too tempting not to forecast workload. This sets up a whole chain of undesirable byproducts. Once we have forecast workload, even a not-too-smart budget examiner can determine just how much money and how many people we really need, thereby limiting the legitimate scope of our activities to bare essentials. If you like austerity, plan programs!

If we have planned programs, someone may even tell us which of the programs has priority and then we are really in trouble, with the attendant perils of having to meet schedules and completion dates. There are some civic reformers who are even able to construct performance budgets based upon such apparently innocuous material as a planned program of work. I urge each of you to consider seriously the consequences of making any such incursion on your freedom of choice even remotely possible.

The actual preparation of the annual work program can be the most difficult task that the planning administrator will face in the sequence of steps discussed in this report. The relative difficulty of the task will depend to a large extent upon the degree to which these other steps have been practiced. Thus, does the agency have a clear understanding of what it has done in the past, or what it intends to do in the future? Does it have a system of work measurement that will allow the planning director to estimate the amount of time needed for various kinds of projects? The answers to these questions, and others like them that have been discussed, are the basis for the planning director to prepare the work program.

The following discussion will be an attempt to outline some of the more important factors that are considered in the preparation of the work program. It should be emphasized again that techniques used by planning offices have not advanced to the point where an exact sequence of steps can be discussed either at great length or in any particular order.

General Procedures

One of the first steps that must be taken is to set some outside limitations on the amount of staff time that will actually be available. The total number of man-hours (or days, weeks, or months) should be computed. Thus, the number of hours in the workweek is multiplied by the number of weeks in the year, less time for vacations, for each staff member, by major divisions and the staff as a whole. These figures represent the maximum amount of staff time available for a year's work, assuming maximum efficiency. Obviously, these figures would be higher than the actual amount of work time that can realistically be expected. However, the figures are quite important since work goals can be more meaningful within the context of the amount of time that is really available. Setting goals that are too high in terms of time available can be extremely demoralizing to a professional staff. If desired, the maximum figures can be tempered with a "planned" amount of sick leave and other work losses that are based on past records. If possible, all these amounts also should be translated into dollar costs. In addition, the administrator should be aware that the figures will not represent the varying talents and experience of individual staff members; one planner may be able to finish a particular task in a week, but another may take two weeks to do the same job.

Three other major constraints will influence the staff time available for specific projects. First, the amount of staff time needed to administer the zoning and subdivision ordinances, as well as other regular administrative duties of the agency, must be subtracted from the total amount of time available. This may be on either an individual or division basis. The second constraint results from the various projects that are still incomplete. More often than not, work on certain plans or studies overlaps various program periods. In practice, there is never a "clean slate." All unfinished projects should be carefully examined when the new program is being prepared to determine their progress and the expected completion dates. Although progress on a study should always be closely watched by the planning director, it is particularly important when the program is being prepared to know within reasonable limits when staff members will be free for other tasks. This is also a good time to review the objectives of ongoing studies and plans. A decision may be made that one component of the park and recreation study be dropped so that the final report can be submitted more quickly to the planning commission. Or, that the major streets plan deserves more detailed study than was originally anticipated.

The third constraint is occasioned by the number and nature of annually recurring projects, such as preparation of the work program, annual report, budget, and capital improvement program. Deadlines for most of these activities will be known sufficiently in advance so that they may be programmed with relation to the anticipated workload. The centerpiece chart shows how these activities are separated from the other kinds of work, and are assigned to certain time periods with a specific amount of staff time devoted to them.

Naturally, the planning commission and the chief executive of the locality will have a strong voice in the selection of the projects. The specific procedures and the roles played by interested public officials vary considerably. As is the case with the establishment of long-range goals for the planning agency, the development of the planning work program can be an educative device for lay planning commissioners. One example of how a regional agency with a number of member communities develops its program is described:12

Prior to the beginning of each year, a letter is sent to all member communities asking them for specific projects that they would like to have accomplished during the coming year either as part of their membership fee or as part of a separate contract with the commission. Response naturally varies, but many communities do ask for work to be done either as part of their membership fee at no extra cost, or by separate contract. There is a general understanding as to the type of work which can be accomplished — particularly at no additional cost. However, this does not prohibit each community from trying to obtain as much work as possible for as little additional payment as necessary. Since we are dealing with people and organizations, responses are not always immediate. However, usually by the date of the February meeting (the reorganization meeting following the election of officers at the January meeting), a pretty fair idea has been gained as to just what the contractual and/or community assistance will be for the forthcoming year. In addition, the commission has, at its annual meeting, selected one or more regional projects upon which it expects the staff to work. In some cases, where staff abilities might be lacking ... in which it is requesting that the commission act as a contracting body, the additional designation of "if funds become available" has been tacked on.

The proposed program is usually presented first by the Director and staff to the Budget Committee who modify it or accept it. It goes from there to the Executive Committee, who do the same. Usually, approval by the Executive Committee is tantamount to approval by the commission as a whole at the quarterly meeting. It is so submitted, however, and receives final acceptance and/or modification there.

At this point there should also be some attempt to assign priorities to projects. Although this can be a very difficult job, it is worth doing for a number of reasons. First, there are probably far more projects that will be taken into consideration than can actually be done with a given staff and budget. Decisions that certain projects will be done, that others will be done only if funds or staff become available, and that others will not be undertaken at all can profoundly affect the long-range effectiveness of the planning agency in carrying out its primary function of guiding urban development. In addition, every planning agency on occasion must drop a project because of a special request from the mayor or city council. In such cases, it is important to know which project can be postponed temporarily without disrupting the entire program, especially if staff must be pulled off a project upon which other staff members are depending on to continue their own work.

Before any meaningful programming can begin, there must be some understanding of both the scope of and length of time needed for each type of project that will be undertaken by the staff. This means that the director should have a reasonably good idea of what needs to be done in a particular study area. Of course, there will be times when this is not possible because not enough is known about the study, or when it is known that only an exploratory effort will be made in the next program period. The significant information about a project would include, but would not necessarily be limited to, its purpose; amount of information already available; the depth of analysis required to fulfill the purpose; the study or survey methods that will be used; the end product in mind (e.g., a working paper or a final report that will become a public document); the major steps or phases of the project; and other similar kinds of factors that will influence the length of time needed to complete this project. This information must then be translated into the anticipated work load.

If the job to be done has some measurable units, the process can be relatively simple. For example, the following paragraphs describe the survey portion of a residential land use study:13

The survey of the residentially zoned areas of the City will begin in June, 1958 with the assistance of eight part-time summer employees from San Diego State College and four junior planner interns. This particular portion of the program will complete the land use survey of the City of San Diego — the industrially zoned areas having been finished and tabulated on IBM cards in February 1957.

The survey of the residential areas will involve considerably more effort in terms of number of items handled. The Assessor's office estimates that there is a total of approximately 130,000 parcels in the City. The Planning Office has on file approximately 20,000 IBM cards which comprise the nonresidentially zoned areas of the City, leaving approximately 110,000 individual parcels of land to be surveyed and tabulated in approximately 63 workdays this summer.

The 1950 Federal census of San Diego included a total of 4701 blocks. Since 1950, approximately 2000 blocks have been added to this amount, increasing the estimated total number of blocks in the City to 6700, less 2200 blocks already surveyed, leaving 4500 blocks yet to be completed.

A breakdown of the estimated workload appears below:

-

Work load by blocks

4500 blocks/ 4 two-man teams = 1125 blocks per team

1125 blocks/ 63 workdays = 18 blocks per day per team

-

Work load by parcels

110,000 parcels/ 4 two-man teams = 27,500 parcels per team

27,500 parcels/ 63 workdays = 437 parcels per day per team

Not all projects will lend themselves to relatively easy measurement as the example above. However, some attempt should be made since the time factor is one of the most important elements of the programming process. Unless some sort of time-recording system is used, the only way to estimate various time factors is by guessing. The planning director must rely on his own personal judgment by comparing about how long it took to do a similar kind of study in another city, how his staff produced on some recent studies that may have similar characteristics, or by contacting other agencies that carried out the same kind of work that is then being contemplated.

Another way to handle the problem is to arbitrarily determine a specific amount of staff time that will be devoted to a particular project. Thus, the decision is made that the staff will do the best it can on study "X" within six months This procedure is much like the one that is usually followed when a "firecall" study must be submitted to the mayor by the end of the month. Obviously, no director wants to run an office with a constant firecall psychology; however, if specific time limits are given and adhered to, staff members may tend to discipline themselves to a greater extent and plan their work in logical segments.

The planning agency that has used a system of work measurement is still faced with the difficult problem of estimating time need for projects. However, its job is far easier than the agency that is starting with no background information. Since there are no standard sources of information to determine "how long it takes to complete a recreation plan for a city of 10,000 population," an agency must rely on how it has performed in the past.

The centerpiece chart describing the work program of the Cincinnati City Planning Commission shows how valuable a time-recording system can be in preparing the work program. A close examination of the chart will show many examples of the various factors that have been discussed in this report. For example, two annually recurring projects have been allocated the same amount of man-hours for 1962 as in 1961. However, it was determined that only 250 man-hours, rather than 550 as in 1961, will be allocated in 1962 for the preparation of the annual report. In other project categories, the amount of time devoted to specific plans and studies is related to the amount of time that was spent on them in 1961. It should be noted that certain projects will need a small amount of time to complete. Only exploratory study was done on others in 1961 in anticipation of swinging into the full project during the following year. In those cases where there is a completely new project, the time allocated is related to the experience on other similar studies. It should also be noted that the time allocated to each of the major divisions, except annually recurring projects, has been increased; that there is a list of reserve projects; and, that planning services are scheduled throughout the year but are not broken down by recorded man-hours.

Unfortunately, it is not possible to tell from the chart why certain projects are scheduled for particular time periods. However, some of the factors that will influence these decisions can be mentioned. The most obvious is that with a specific number of staff members only a given amount of work can be handled at a time. If a few staff members have special competence in certain areas, program timing will reflect this fact. In some cases, field work will have to be planned for the summer months. In other cases, such as submission of the capital improvement program, there is a definite submittal date and report preparation must be planned accordingly. In still other cases, the planning agency may be doing a project in cooperation with another agency. Finally, certain kinds of planning studies must be completed before work can begin on others.

Execution of the Work Program

Carrying out the work program on schedule should be one of the major goals of the planning agency. Success in meeting its objectives is both a direct and indirect measure of how it is meeting its responsibilities as a public planning agency. The planning director has primary responsibility for seeing that the program is carried out. His success depends to a great extent upon his managerial and leadership abilities. A few words can be said about some of the tools that can be helpful in accomplishing this end.

First, there is the program itself as the guide to the staff's work. One planner has said that

A work program is like a personal budget. It has a great significance immediately after it is prepared, with daily diminishing returns thereafter. Yet it is there, in the chief's top drawer, to be pulled out as a reminder to him and the working staff that there still are specific jobs to be done by a given date. Then things fall into line for a few days, or until the Urgent takes the place of the Important.14

One method of keeping track of how the staff is doing is used in many planning agencies whether there is a formal programming procedure or not. It is simply the use of a progress chart as shown in Figure 4. A list of all contemplated projects is made on the chart, along with breaking down the work on each project into logical phases as shown across the top of the chart. Its importance lies in the fact that a written record is kept; its easy administration lies in the fact that it is so simple to prepare and maintain.

Figure 4. Reproduced from the 1959–1960 Annual Report of the Glendale (California) Planning Division

The most accurate way to keep track of the progress on the work program is through the use of a work-measurement and time-recording system. At this point the system that was used to prepare estimates for the actual preparation of the work program now becomes a feedback device for administrative control. With either monthly, quarterly, or semiannual summaries of staff work activity, the director can assess the progress that has been made. Here, too, is an opportunity to decide that the time for certain work will be extended or curtailed. If a great many "firecalls" have been answered in the previous time period perhaps extensive revision of the program for the remaining year may be necessary.

Most important of all, the planning director and staff know where they have been and where they are going.

REFERENCES

- The Technique of Municipal Administration (Chicago: International City Managers' Association, 1958), p. 136.

- Daniel L. Kurshan, "Administration of a Planning Office," Planning 1958, p. 205.

- Letter from Richard W. McGinnis, Director, Lorain County (Ohio) Regional Planning Commission, March 8, 1962.

- Report to the Board of City Planning Commissioners, City of Los Angeles, on the Los Angeles City Planning Department (Cambridge, Mass: Adams, Howard and Greeley, Consultants, 1956).

- The Technique of Municipal Administration, op. cit., p. 352.

- Information about this system is based upon a letter from Harmon T. Merwin, Director, Franklin County (Ohio) Regional Planning Commission, June 4, 1962.

- A complete explanation of the system is described in Time-Cost Recording System (Lexington, Kentucky: City-County Planning Commission).

- Progress on this system was first discussed by H. W. Stevens, in "For the Record," Journal of the American Institute of Planners, Vol. XXVII, No. 3, August 1961, pp. 212–215. The present discussion is intended to review the basic elements of the system and, in addition, to report how the system has been used in work programming.

- Cost Recording System (Cincinnati: City Planning Commission, August 1961), p. 1.

- Ibid.

- Kurshan, op. cit.

- McGinnis, op. cit.

- Interoffice memo, San Diego City Planning Commission, no date.

- Letter from John D. McLucas, Acting Director, Inter-County Regional Planning Commission, Denver, March 23, 1962.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The ASPO Planning Advisory Service wishes to thank the following people for their opinions and extended comments on the subject of work programming:

Carl B. Genrich, Jr., Principal Planner-Administration, Pittsburgh Department of City Planning; Lloyd T. Keefe, Planning Director, Portland (Oregon) City Planning Commission; Richard W. McGinnis, Director, Lorain County (Ohio) Regional Planning Commission; John D. McLucas, Acting Director, Inter-County Regional Planning Commission, Denver; Harmon T. Merwin, Director, Franklin County (Ohio) Regional Planning Commission; L. S. O'Gwynn, Chief, Master Plan Section, Baltimore Department of Planning; Frank S. Skillman, Director-Secretary, San Mateo County (Cal.) Planning Commission; Herbert W. Stevens, Director of City Planning, Cincinnati City Planning Commission; and Reginald R. Walters, Chief, Comprehensive Plan Division, Planning Department, Metropolitan Dade County, Florida.

APPENDIX A IDENTIFICATION OF CURRENT RPC PROJECTS OR PROCESSES

Franklin County (Ohio) Regional Planning Commission

| Major Classification | Project or Process |

|---|---|

| R - Regional |

01 Physiographic Studies 02 Handbook of Local Government 03 Regional Base Map 04 Vacant Lot Study 05 Urban Development Studies 06 Morse Road Study 07 Regional Annexation Principles 08 Outerbelt and S.R. 161 09 Population Study 10 Land Use Proposals 11 Principles for Non-Shopping Center Commercial 12 Land Use Categories 13 Planning Area Delineation 14 Inventory, Evaluation, Water Data 15 Regional Representation 16 Regional Program Planning 17 Development Coordination 18 Public Information and Service 19 Mapping - Urban Areas |

| C - County |

01 Preparing Subdivision Procedures 02 Revision of Subdivision Regulations 03 Revision of County Zoning Resolution 04 Zoning Consequences 81 County Program Planning 82 Intra-County Development Coordination 83 Public Information and Services 84 Mapping – 500' L.O. Maps 85 Mapping – 800' Township Maps 86 Zoning Cases 87 Subdivision Review 88 Review of Land Splits |

| L - Local Assistance |

01 Grove City Mapping 02 Canal Winchester Annexation Study 03 Worthington Comprehensive Plan Studies (701) 04 Canal Winchester Comprehen. Plan Studies (not 701) 05 Canal Winchester Subdivision Regulations 06 Review Canal Winchester Subdivisions 07 Canal Winchester 701 81 Local Assistance Programming and Administration |

| A – General Administration |

01 Non-bookkeeping clerical 02 Maintenance 03 Accounting and Budgeting 04 Annual Report 05 06 Legislative Coordination 07 Library Operation 08 Staff Recruiting 09 Staff Development 10 Staff Meetings 11 Commission Meetings 12 OPC, HOP 81 Program Planning 82 Administration 83 Public Information and Service 98 Vacation 99 Sick Leave 00 Personal Business |

APPENDIX B WORK CLASSIFICATION LIST

Lexington (Kentucky) City-County Planning Commission

| 1000 (1000-2999) | OFFICE OF DIRECTOR |

|---|---|

|

1100 1110 1120 1130 1140 |

Community Information Operations Organizing Information Program Individual Contact (office, news media) Group Contact (meetings, speeches, teaching) Individual and Group Contact (Newsletters, Annual Report, Special Reports) |

|

1200 1210 1220 1230 1240 1250 |

U.S. Federal Operations Legislation Legislation Workable Program 701 Program Community Renewal Program Open Space Program |

|

1300 1310 |

State of Kentucky Operations Enabling Legislation |

|

1400 1410 1420 |

Lexington and Fayette County Government Operations Informal Meetings Legislative Meetings |

|

1500 1510 1520 1530 1540 1550 |

Planning Commission Operations Organization (Bylaws, committees, etc.) Membership Records Informal Meetings Regular Meetings Agenda and Minutes Preparation |

|

1600 1610 1620 |

Staff Operations – General Miscellaneous correspondence, telephone, visitors, filing Library, literature and mail circulation, newspapers |

|

1700 1710 1720 1730 1740 |

Staff Operations – Fiscal and Property Control Budget (yearly preparation, monthly upkeep) Payroll (salaries, taxes, etc. for individuals and whole staff) Accounts (procurement and payment) Property Inventory (yearly, monthly upkeep) |

|

1800 1810 1820 1830 1840 1850 1860 |

Staff Operations – Housekeeping Staff Organization Employee Records Time-Cost Records Regulations Recruitment and Resignation Performance Evaluations |

|

1900 1910 1920 1930 |

Staff Operations – Work Program Preparation of Program Coordination with Staff Coordination with Others |

|

2000 2010 2020 |

Professional Organizations American Institute of Planners American Society of Planning Officials |

|

3000 (3000–4999) |

PLANNING SERVICES DIVISION |

|

3100 3110 3120 3130 |

Division Operations Miscellaneous correspondence, telephone, visitors, filing Division work program organization and coordination Information, education, coordination with outside groups |

|

3200 3210 3211 3212 3213 3214 3220 3221 3222 3223 3224 |

Current Planning Section Section Operations Organization Special Reports Information and Education Base Maps Updating Community Development Plans Transportation Land Use Community Facilities Urban Renewal (projects, workable program, etc.) |

|

3300 3310 3311 3312 3313 3320 3321 3322 3323 3324 3325 3326

3330 3340 3350 |

Subdivision Regulation Section Section Operations Organization Special Reports Information and Education Plat Review Special Sketch Plans Office Check (letter writing, regulations) With Other Agencies (sending copies, getting replies, etc.) In Field With Developers With Subdivision Committee (Enter Planning Commission meetings under Office of Director) Maintaining Statistical Records Performance Bond Administration Property Numbering Problems |

|

3400 3410 3411 3412 3413 3420 3421 3422

3423 3424 |

Zoning Ordinance Amendment Section (Planning Commission Work) Section Operations Organization Special Reports Information and Education Administration of Amendments Filing Staff Investigation and Report (Place Planning Commission meeting time under Office of Director) Planning Commission Final Report Legislative Hearing and Adoption |

|

3500 3510 3511 3512 3513 3520 3521 3522 3523 3524 3525 |

Zoning Ordinance Appeal Section (Board of Adjustment Work) Section Operations Organization Special Reports Information and Education Administration of Appeals Filing Staff Investigation and Report Board Hearings Minutes and Agenda Preparation Follow up on Board Actions |

|

5000 (5000–6999) |

ADVANCE PLANNING DIVISION |

|

5100 5111 5120 5130 5140 5150 |

Division Operations Miscellaneous correspondence, telephone, visitors, filing Division work program organization and coordination Information, education, coordination with outside groups 701 Application and Administration Community Renewal Program |

|

5200 5210 5211 5212 5213 5214 5215 5216 5217 5218 5219 5220 5221 5230 5231 5232 5233 5234 |

Research and Analysis General Base mapping Area delineations Historical research Economic research Sociological research Physical research – land use survey Physical research – land conditions & resources Physical research – vacant land Physical research – quality of structures Physical research – aesthetic features Physical research – property values Specific Plan Research Transportation Research Community Facilities Research Public Utilities and Related Facilities Research Financial Research |

|

5300 5310 5320 5330 5340 5350 |

Preliminary Plan Formulation Land Use Plan Transportation Plan Community Facilities Plan Public Utilities Plan Overall Community Development Plan |

|

5400 5410 5420 5430 5440 5450 |

Preliminary Plan Testing Land Use Plan Transportation Plan Community Facilities Plan Public Utilities Plan Overall Community Development Plan |

|

5550 5510 5520 5530 5540 5550 |

Final Plan Proposals Land Use Plan Transportation Plan Community Facilities Plan Public Utilities Plan Overall Community Development Plan |

|

5600 5610 5611 5612 5613 5620 5621 5622 5623 5624 5625 |

Implementation Devices General Approaches Adoption of plans Local government referral Citizen action Specific Documents Zoning ordinance Land subdivision regulations Official map Public financial program Urban renewal program |

APPENDIX C WORK CLASSIFICATION LIST

Cincinnati City Planning Commission

PART I

| PROJECT NUMBERS | |

|---|---|

|

01 |

Administration |

|

01 - 000 |

General Answering Questions of Public Office Administration |

|

01 - 100 |

Operations and Program Cost Recording Study Space Utilization |

|

01 - 200 |

Finance Payrolls Purchasing Annual Operating Budgets |

|

01 - 300 |

Personnel Recruiting Training Performance Reports |

|

01 - 400 |

City Planning Commission and Council Council and Council Committee Meetings Commission Rules and Regulations |

|

01 - 500 |

Public and Professional Relations (External Relations) Speeches Professional Organizations Exhibit Materials Annual Report |

PART II

| PROJECT NUMBERS | |

|---|---|

|

02 02 – 000 001 002 003 004 005 006 007 008 009 010 011 012 013 014 015 |

Advance Planning – City and Metropolitan Area General Population New Zoning Ordinance Motorways Group Housing Amendment Home Occupations Amendment Historic Buildings and Sites View Zone Truck Terminals School Plans and District Maps Recreation Plans and Maps Residential Areas Study Capital Improvement Program Plan Brochure and Exhibit Demonstration Grant Research Community Separation and Hillsides |

|

03 03 – 000 100 03 – 100 – 70 – 10 – 40 200 300 400 |

Planning Services General Zoning Cases Field Survey Reports, Hearings Subdivisions Land Use Records Revisions to 200' Scale Base Maps Referrals |

|

04 04 – 000 001 002 003 004 etc. |

Urban Renewal General Laurel-Richmond Kenyon-Barr Kenyon-Barr 1 Kenyon-Barr 2 |

|

05 05 – 000 001 002 003 004 005 etc. |

Advance Planning – Local Area Projects General Millcreek Expressway Northeast Expressway - Norwood Lateral Northwest Expressway Sixth Street Expressway Colerain Avenue |

SUBJECT EMPHASIS BREAKDOWN

Sub-lists are to indicate nature of content, not separately recordable subjects.

10 – Circulation

Air

Rail

Water

Motor Vehicle

Parking

Mass Transit

Pedestrian

20 – Utilities

Gas and Electricity

Water

Sewer

Communications

Fire Protection

Health Facilities

30 – Land Use

Residential

Commercial

Industrial

Institutional

Public

Schools

Parks and Recreational

40 – Sociology and Culture

Population

Service Agencies and Programs

Historical

Aesthetics

50 – Economics

Volume

Employment

Income

Finance

60 – Physiography

Meteorology

Topography

Geology

Geography

70 – Legislation and Government

Governmental Structure

Municipal Legislation

State and Federal Legislation

PHASE EMPHASIS BREAKDOWN

Sub-lists are to indicate nature of content, not separately recordable phases.

10 – Research and Analysis

Compilation of Existing Data

Original Surveys

Study of Results

Report of Results

Problem Identification

20 – Idea Formulation

Develop Concepts

Trial drafts, maps and reports

Study of Findings of Research

Preparation of Reports for Testing

30 – Testing

Meetings with Public Officials

Meetings with Citizenry

Application to Cases

Revision of Report

40 – Proposals

Public Hearings

Drafting proposal reports

Drafting proposal maps

Presentation of Report

Documentation

50 – Implementation

Coordination with Public Agencies

Coordination with Private Interests

Study of Counter Proposals

Revision of Report and Plans

Documentation

60 – Non-Productive Time

Vacation Time

Sick Leave

Holiday

Prepared by Frank S. So. Copyright © 1962 by American Society of Planning Officials