Highway-Oriented and Urban Arterial Commercial Areas

PAS Report 177

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 177 | September 1963 |

Highway-Oriented and Urban Arterial Commercial Areas

Download original report (pdf)

Prepared by James H. Pickford

It is well known that the location of businesses on major thoroughfares contributes to traffic congestion, hazardous intersections and unsightly appearance. Recent studies have shown, however, that a strong case can be made for locating certain types of businesses on major highways as a convenience to the traveler. Gasoline stations and restaurants are among the more obvious examples. There are, furthermore, firms that tend to locate on major highways because of space requirements for parking and loading operations, and the need for convenient access to all parts of the community. Building materials establishments are examples of this type. Such businesses are not essential to the traveler or to the operation of the highway system; rather they require location on major thoroughfares for efficient operation.

The importance of both types of highway-oriented commercial uses in the business structure of the community is considerable. In a recent census of business firms outside the central city in one metropolitan area, more than 18 per cent were classified in the highway-oriented category, and nearly 16 of this 18 per cent were located in strip commercial areas.1

If it is conceded that highway-oriented commercial development is essential to the business welfare of the community, it should be possible to plan for it and to provide adequate controls. On the surface, the problem might appear uncomplicated and easily solved. For example, if a string of businesses were to be set back along a frontage road with adequate off-street parking and common controlled access from the highway to reduce traffic conflicts, objections to the strip commercial development would undoubtedly be diminished. And if adequate screening along the entire string insured against loss of neighborhood character and maintained land values of nearby residences, many of the objections to the visual aspects of this type of business center would be eliminated.

But much more refinement is needed than most cities now use to select permitted uses in such string-type developments if they are to reduce dangers of over-expansion of the areas. Many retail uses do not mix well with highway-oriented uses, and should be restricted to other types of shopping areas. At the same time, provisions must be made for those businesses that do require location on a highway and that cannot be forced into the type of compact development typical of shopping centers.

If the number of inquiries received by ASPO Planning Advisory Service seeking information on methods of planning for and controlling commercial development along highways and major thoroughfares can be taken as an indication, this problem ranks high on the list of those of major concern to local planning agencies. Our understanding of the functions of many other land use categories — residential areas, shopping centers, central business districts, planned industrial areas — within the over-all land use structure has led to relatively sophisticated controls. New zoning techniques, such as aesthetic controls, floor-area ratios, planned development provisions and performance standards, are now commonplace and are being applied to guide future development. Unfortunately, our understanding of another major land use type — highway-oriented establishments — appears to be inadequate; efforts to provide intelligent controls have been sporadic.

This report examines some of the studies that clarify the role of highway-oriented establishments within the community business pattern, planning studies that suggest community policy with regard to this land use category, and some of the attempts that have been made to zone for highway business districts.

Business Location Characteristics

Ever since the central place theory was introduced in this country a little more than 20 years ago to explain the size, number and distribution of towns, it has played an important part in theoretical works on the spatial structure of retail activities. The theory has been summarized as follows:

- The basic function of a city is to be a central place providing goods and services for a surrounding tributary area. The term "central place" is used because to perform such a function efficiently, a city locates at the center of minimum aggregate travel of its tributary area, i.e., central to the maximum profit area it can command.

- The centrality of a city is a summary measure of the degree to which it is such a service center; the greater the centrality of a place, the higher is its "order."

- Higher order places offer more goods, have more establishments and business types, larger populations, tributary areas and tributary populations, do greater volumes of business, and are more widely spaced than lower order places.

- Low order places provide only low order goods to low order tributary areas; these low order goods are generally necessities requiring frequent purchasing with little consumer travel. Moreover, low order goods are provided by establishments with relatively low conditions of entry. Conversely, high order places provide not only low order goods, but also high order goods sold by high order establishments with greater conditions of entry. These high order goods are generally "shopping goods" for which the consumer is willing to travel long distances, although less frequently. The higher the order of goods provided, the fewer are the establishments providing them, the greater the conditions of entry and trade areas of the establishments, and the fewer and more widely spaced are the towns in which the establishments are located. Ubiquity of types of business increases as their order diminishes. Because higher order places offer more shopping opportunities, their trade areas for low order goods are likely to be larger than those of low order places, since consumers have the opportunity to combine purposes on a single trip, and this acts like a price-reduction.

- More specifically, central places fall into a hierarchy comprising discrete groups of centers. Centers of each group perform all the functions of lower order centers plus a group of central functions that differentiates them from and sets them above the lower order. A consequence is a "nesting" pattern of lower order trade areas within the trade area of higher order centers, plus a hierarchy of routes joining the centers.2

Strip or ribbon commercial centers, however, do not fit so neatly into the theory of hierarchical business centers.

First, it must be recognized that string street-type centers serve different demands than do nucleated centers, demands not for immediate consumer goods purchased from the home, but presumably demands associated with people moving along major urban arterials. String street-type centers show clear relations to the pattern of traffic flow in the city, and it may be inferred that they serve people on the move (i.e., satisfying auto-based demands). Spatial distribution of demands in this case is not approximated by the population or housing map, as in the case of nucleated centers, but by the traffic flow map. Also, shopping is not by people walking to several stores in a center but is of a single-purpose character from an immediately parked automobile. Hence, businesses need not nucleate in centers to minimize the costs of shopping; they can string along major traffic arteries and still be located central to the maximum profit areas at their command.3

Efforts to classify the string-type business phenomenon with the central place theory have been undertaken by detailed examination of the locational tendencies of individual retail establishments. One such classification scheme,4 illustrated in Table 1, shows four basic types of business groupings aside from the central business district. They have been defined on the basis of spatial association and location as:

Nucleated Types. The types of businesses occurring most commonly in and normally associated with central places or shopping centers are clothing, shoe, variety, drug, food and department stores, banks, professional offices, and so on. These businesses occur in neighborhood, community and regional shopping centers, and, of course, in central business districts. All of these centers have fairly well-defined trade areas with the low order (neighborhood) centers within the trade areas of high order (regional) centers.

Urban Arterial Types. Furniture, appliance, and fuel dealers, bars, and automobile repair establishments frequently locate only within the built-up areas of cities, and along major traffic arteries rather than in nucleated centers. These business types contribute to the familiar ribbon or strip developments; and may constitute the fringe, secondary belt or frame of the central business district. In other parts of the city, urban arterial business types depend more on the major thoroughfare than on the CBD as the primary factor in location.

Highway-Oriented Types. Wherever there is high traffic volume, businesses such as gas stations, restaurants and motels tend to locate to meet the demands of the traveler. Highways also provide access to large cheap sites that attract lumber yards, building supply establishments and many repair services. Together, the business types supplying traveler demands and those requiring large sites with highway access constitute the highway-oriented business type group. These businesses differ from those in the urban arterial group in that they are highway-oriented regardless of whether the highway is within the city or is an intercity route.

Localized Business Types. Certain business types are usually found grouped together rather than dispersed throughout the city. A good illustration of this type of district is the automobile row, comprised of new and used car and spare parts dealers, and repair facilities.

Another study adding to the knowledge of retail spatial characteristics is that undertaken for suburban King County (Seattle), Washington.5 The classifications used are divided into two general sections: highway-oriented developments and nucleated centers. The highway-oriented section is subdivided into isolated (300 feet separating one establishment from other establishments) and strip categories. The nucleated facilities, again excluding the central business district, are classified according to size as:

- Isolated — an establishment not associated in terms of areal distance with any other retail land use. Again the distance of 300 feet applies.

- Small Nucleations — a retail land use conformation containing two to eight retail establishments.

- Medium Nucleations — a retail land use conformation containing nine to thirty-three retail establishments.

- Large Nucleations — a retail land use conformation containing thirty-four to eighty-six establishments.

- Sub-Regional Nucleations — any nucleation larger than eighty-six establishments.6

The sub-regional nucleation classification is further subdivided to emphasize the distinctive differences between the older suburban shopping districts and the newer and highly automobile-oriented shopping centers. This distinction follows the Horwood-Boyce core-frame concept,7 wherein retail firms that are pedestrian-oriented and intensive land users of the core are distinguished from those firms that are automobile-oriented and extensive users of the frame.

The locational tendencies for individual firms in King County are presented in detail in Tables 2 and 3. In comparing the classification system devised by Berry (Table 1) with that used in the King County study, it should be remembered that the former was developed by examining central cities that are fairly well built up and that contain a number of older shopping areas. The King County study, on the other hand, was carried out in a growing suburban area. Nevertheless, the basic differences between nucleated centers and highway-oriented facilities are confirmed by both studies.

(Download the PDF of this report from the link at top to see Tables 1, 2, and 3.)

These studies provide enough information to permit generalizations concerning the spatial structure of retail and service businesses within urban areas, and are particularly helpful in understanding the nature of ribbon-type business development.

First, the central place theory cannot be used as an all-inclusive explanation of the urban business pattern. Other locational factors, in addition to some degree of centrality to population concentration, are important. The availability of large or inexpensive sites, or both, and access to large volumes of traffic are of considerable importance to certain firms in the highway-oriented and urban-arterial or frame groups. To a number of firms in highway strip areas, however, the availability of large and inexpensive sites is the most important locational factor.

Second, it may be generalized that the lower in the hierarchy of nucleated centers an individual firm locates, the more important as a primary locational factor is the large or inexpensive site. The higher in the hierarchy of nucleated centers a firm locates, the more important centrality and threshold become.

These findings make it possible to more realistically evaluate planning and zoning practices applicable to the urban business pattern.

Planning Considerations

Many contemporary planning studies and zoning practices are inadequate in the treatment of highway-oriented and urban arterial business uses as a part of the over-all business pattern. The traditional argument of the conceptual basis for planning of commercial land use has been described as follows:

Reduced to its simplest form, the argument is that there are three types of retail and service business, convenience, shopping, and specialty, and that as a result there need only be three types of shopping centers, neighborhood supplying convenience goods, community supplying both convenience and shopping goods, and regional supplying all types of goods and services. This neat trichotomy fits in well with ideas of neighborhood and community planning units and proponents of the typology have found support in the hierarchical notions of central-place theory. Such is the basic planning concept of an efficient business structure.8

This planning concept as carried through to zoning practice is questionable because it is not supported by empirical findings of studies such as those described earlier in this report.

... this theoretical trichotomy describes only the nucleated business centers found in reality. It describes neither highway-oriented nor urban arterial business districts; neither does it suggest that localized developments can exist. The planning concept of business structure is thus inadequate. A business structure zoned solely according to such a concept would allow only nucleated centers in most of the urban area. Highway-oriented, urban arterial and localized developments could take place only in the unrestricted business and commercial zones.9

Commercial Land Use Studies

An example of a comprehensive planning study that recognizes the business types beyond the nucleated group is the Tulsa Metropolitan Area Comprehensive Plan. This plan establishes seven commercial use groups, only one of which concerns nucleated shopping centers and districts. Typical uses found in each group, and the reasons for each grouping, are shown in Table 4.

Nucleated business centers are then defined by type (neighborhood, sub-community, community and regional) and standards are established for each. Standards for the other six commercial use groups are given in Table 5.

(Download the PDF of this report from the link at top to see Tables 4 and 5.)

The Tulsa plan also includes general locational and site development standards applicable to all commercial use groups:

General Commercial Locational Standards:

- Intersection of two major streets and/or adjacent to expressways.

- On major streets on the fringe of residential neighborhoods.

- Not abutting other similar commercial concentrations (i.e., shopping center to shopping center, highway business to highway business), and not across the street from other commercial concentrations which creates "split" centers.

- Served by an adequate major street and/or expressway system.

General Commercial Site Development Standards shall be of adequate acreage to provide:

a. sufficient off-street parking (customer and employee) facilities (i.e., ratio of four square feet of customer parking to one square foot of building area in shopping centers);

b. off-street loading facilities of adequate size, shape, and location;

c. sufficient and well-located ingress and egress points controlled to prevent traffic tie-ups on the adjacent major street,

d. adequate physical screen and area to serve as buffer between the commercial use and abutting residential areas (i.e., an additional 100 percent of the building area should be utilized for employee parking, off-street loading and buffer for convenience and neighborhood shopping centers, and fifty percent of the building area for sub-community, community and regional shopping centers);

e. building set-backs from major streets.10

If planning standards similar to these, combined with carefully drafted statements covering the objectives and goals for commercial land use within a city, were judiciously carried out, land use controls for non-nucleated business types might reach a level of sophistication comparable to shopping center controls.

Another example of a comprehensive planning study that recognizes business types independent of the hierarchy of shopping centers is Philadelphia's "Plan for Commerce,"11 adopted in 1960. In addition to the central business district, the plan calls for 5 regional shopping centers, 21 intermediate centers, 169 local centers, and 91 free-standing commercial areas.

Free-standing commercial areas, as described in the Philadelphia study, are designed for businesses that do not "need a supporting cluster of other stores for commercial success. Each establishment stands by itself and does not depend on pedestrian shopping from store to store. Free-standing areas exhibit no hierarchy of size and bear little relationship to the city's residential areas."12 The stores cater to customers who come by automobile and who usually are making a single-purpose trip. These business places are defined as having one or more of the following characteristics:

- Their customer is the motorist himself.

- They are large space-users and have low rent-paying ability per square foot.

- Their customers do not make frequent purchases.

- They combine retail, wholesale, service and repair in various ways.

- Their market is other businesses, not households.

- Their market area is large and thin.13

To reduce the conflict between the requirements for free-standing businesses and those for the nucleated business group, four locational criteria are set forth for the free-standing group:

- On the periphery of regional shopping centers and of some intermediate shopping centers.

- On the periphery of the central business district.

- In clusters on the arterial streets.

- On the periphery of industrial areas.14

The plan concedes that not all free-standing businesses (existing in 1960) require such locations. Some can function in shopping centers as well as in independent areas. It proposes that the future business location pattern include existing areas of free-standing businesses around shopping centers, but shortened and widened for more compact design. Access control techniques are recommended to minimize traffic conflict.

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the two form components of the Philadelphia commercial land use plan: the nucleated centers, including the central business district, and the free-standing areas. The sketch maps clearly distinguish between the nucleated and the urban arterial business areas.

Source: "The Plan for Commerce," Comprehensive Plan for the City of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: City Planning Commission, 1960), p. 54.

While there are differences of approach in the commercial land use plans of Tulsa and Philadelphia, both recognize the validity of setting aside ribbon areas along highways and major streets for business use. Furthermore, they acknowledge that such areas must be provided for certain types of commercial use in order to sustain business vitality throughout their respective planning areas. Neither plan, however, relegates such uses to unrestricted general areas; they specifically delineate those areas best suited for arterial business types.

Highway Renewal Studies

In spite of the huge new interstate system, the bulk of the country's traffic continues to be carried by the older highways. Many of these useable highways, however, are rapidly becoming snarled because of uncontrolled ribbon development. To neglect them can only lead to writing off an enormous public and private investment and constructing new roads at a cost many times higher than that of preserving the original roads. This fact is so obvious, it is surprising so few communities have undertaken comprehensive studies seeking ways to preserve and renew existing highways and the lands adjacent to them.

One of the most thorough studies undertaken is the one prepared three years ago in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area.15 It is a planning study, not an engineering study, of a 25-mile stretch of urban highway being choked by strip development and innumerable intersections. This major route connects the northern suburbs with the city, and bisects three municipalities.

Detailed suggestions are made for physical improvements to control access to abutting properties and to control traffic movements to and from the highway. In built-up areas, marginal access roads are proposed to supersede individual access wherever there are a minimum of three adjacent uses. A series of left turn storage islands at major intersections, together with prohibition of left turns at other intersections, is proposed to increase traffic flow. The report also proposes a number of specific changes in local zoning ordinances to encourage a better pattern of land use and to provide for the gradual elimination of structures that interfere with the proper functioning of the highway and the implementation of the future land use plan. Responsibilities for the work, costs, and necessary legislative action at the state, county and municipal levels of government are recommended.

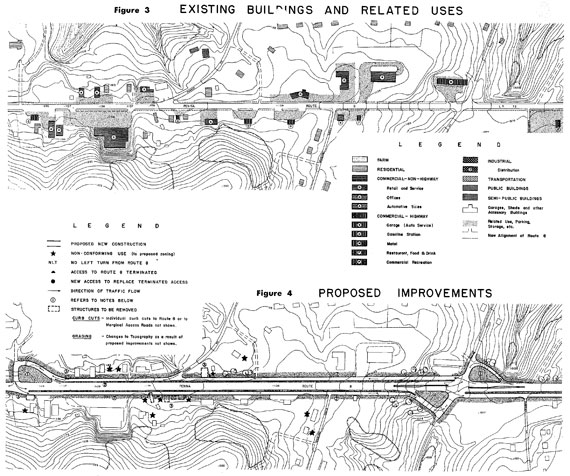

Figure 3 illustrates existing conditions along a small stretch of the highway, and Figure 4 shows the same area after incorporation of the recommendations. The circled numbers in Figure 4 indicate improvements explained in detail within the report. Analysis of the plan shows that the improvement of this section (approximately one mile) can be carried out with the elimination of only two business establishments, both gasoline stations. The improvements would also remove four residences.

Source: Route Eight Study—A Proposal for Highway Renewal (Pittsburgh: Regional Planning Association, 1959), pp. 46 and 47.

The problems of state-local and inter-local coordination in carrying out studies and action programs of this kind are complex, and probably have discouraged a number of local planning agencies from undertaking such projects. Proper development of vacant areas and redevelopment of built-up areas along our urban arterial roads will therefore ultimately depend on how much the various governments are willing to cooperate.

Zoning Factors

The studies reviewed earlier in this report suggest that the business structure of a city tends to be far more complex than the simple nucleated shopping center hierarchy (neighborhood, community, regional) below the central business district. They also suggest that there is an arterial business hierarchy (highway-oriented services, urban-arterial, automobile row) that must be considered. The distinction between nucleated and arterial functions is important, since one type has one set of locational patterns and the other has an alternate set. These differences should be reflected in the zoning ordinance.

Intent Statements

Policy statements quite often appear in comprehensive plans. The Tulsa and Philadelphia plans are examples that set forth criteria to guide the planning commissions in making recommendations on proposed business centers. These declarations may also be reflected in the zoning ordinance, taking the form of a statement of purpose or intent appearing in a section introducing highway or arterial business regulations.16

The following intent statement is more complete than most, and accurately describes the reason for the establishment of the district.

The HC Highway Commercial District is established as a district in which the principal use of land is for establishments offering accommodations, supplies, or services to motorists, and for certain specialized uses such as retail outlets, extensive commercial amusements, and service establishments which although serving the entire village and its trading area do not and should not locate in the central business district or neighborhood districts. The HC Highway Commercial District will ordinarily be located along numbered state or federal highways or other highways designated as major streets.

For the HC Highway Commercial District, in promoting the general purposes of this ordinance, the specific intent of this section is:

(a) To encourage the construction of, and the continued use of land for, commercial, service, and amusement uses serving both local and long distance travelers;

(b) To provide for orderly development and concentration of such uses within the HC Highway Commercial District as designated on the zoning map;

(c) To provide appropriate space, and in particular sufficient depth from the street, to satisfy the needs of modern commercial development where access is entirely dependent on the automobile;

(d) To encourage the development of the district with such uses and in such a manner as to minimize traffic hazards and interference from highway-oriented businesses.

(Grayslake, Illinois, proposed 1960)17

Another characteristic of arterial business zones is stressed in the next extract by calling attention to special development standards required to minimize traffic hazards.

The CT District is intended to provide for establishments offering accommodations, supplies, or services especially to motorists, and for certain uses such as commercial amusements and specialized automotive and related sales and service establishments which serve persons coming to them from large trading areas by automobile. Such uses ordinarily do not seek locations in shopping centers and therefore must be provided for at independent locations. The CT Districts, when appropriate, will be located along major thoroughfares. Special development standards are incorporated in the district regulations in order to provide for orderly development and to minimize traffic hazards.

(Santa Clara County, California, 1937 as amended)The intent statement below points out the vehicle-oriented nature of the commercial activities and the need for visibility.

The intent of this district is to provide suitable locations for those commercial activities which function relatively independent of intensive pedestrian traffic and proximity of other firms. These activities typically require direct auto traffic access, and visibility from the road. (These characteristics which contribute to the sound functioning of these activities are on the other hand characteristically detrimental to BI Business Intensive District.)

(Mt. Clemens, Mich., 1962)

The minimum size of the zoning district is set forth in another ordinance.

Purpose: To provide for retail commercial, amusement and transient residential uses which are appropriate to thoroughfare location and dependent upon thoroughfare travel. C-T districts are to be established in zones of two acres or larger, and shall be located only in the vicinity of thoroughfares, or the service drives thereof.

(Fremont, Calif., 1957)

All of these statements help to spell out the differences between the highway and urban arterial-oriented business districts and other business and commercial zones.

Permitted Uses

The analysis of zoning ordinances made for this report showed that use provisions for different business districts are seldom clearly distinguished. Surprisingly few ordinances make any distinction between stores that prefer location in shopping centers and other uses unsuitable for such locations.

The classifications of uses in Tables 1, 2 and 3 will be helpful as an initial checklist of business developments appropriate to each type of business zone. Another valuable source is the technique used in Tulsa, which resulted in the groupings shown in Table 4. Their Commercial Land Needs18 study classifies businesses, as listed in the U. S. Bureau of the Census' Standard Industrial Classification Manual, in groups of compatible uses, providing a somewhat different separation of uses appropriate for each type of business zone. The use group idea in the New York City and Bismarck, North Dakota, zoning ordinances also employs the technique of grouping compatible uses. Few other ordinance drafters, however, follow this approach. The method can be helpful in overcoming some of the problems of drafting business district provisions by clarifying the spatial and locational characteristics of business types.

There is a lack of consistency among the zoning ordinances examined in treatment of special uses. One ordinance states that "a Conditional Use Permit is required for any other use which is not specifically permitted in this District." At the other extreme, the Mt. Clemens, Michigan, ordinance lists only those uses requiring outdoor storage as special exceptions to the list of uses normally permitted in limited commercial and single-family residential districts. The variety in treatment, of course, reflects the substantial differences in the purpose and intent of the highway business districts in each community.

Dimensional Standards

The dimensional standards shown in Table 6 (download the PDF of this report from the link at top to see Table 6) were taken from several zoning ordinances, and apparently apply in most instances to business centers in outlying areas, rather than in the more intensely developed frame areas. While there appears to be general agreement on the requirements for yards and building height, there is a wide variation on other requirements.

Lot Area and Width. Establishment of minimum lot area and width standards, especially for commercial areas, are matters about which reasonable men will disagree. These requirements, particularly in arterial business zones, are desirable to permit adequate space for parking, loading, landscaping, and expansion. In addition to clearly affecting the density of arterial business use, they will have a direct effect on traffic-carrying capacity of the major street. Much of the clutter of ribbon commercial development could be better controlled by appropriate spacing of buildings. Minimum lot standards should probably call for no less than fifty feet of width and an area of at least 5,000 square feet.

Floor Area Ratio. Only two ordinances make use of floor area ratios. This device will probably come into wider use in the future as zoning ordinances are updated. The automobile, of course, is the dominant means of transportation in arterial business areas, and the intensity of development must be low to provide off-street parking, Sufficient room on the lot should also be provided to allow adequate space for landscape buffers, loading areas and marginal access roads.

Floor area ratios for highway business zones probably should not exceed 0.35 — that is, 35 square feet of floor space for each 100 square feet of lot area. The ratios should only slightly exceed the allowable lot coverage to keep the ground-level building area at a small fraction of the site area.

Lot Coverage. As the table indicates, there does not appear to be a consensus on lot coverage requirements. Coverage requirements, however, should be low to permit landscaping and screening and might possibly vary by type of arterial business use. Low coverage would be appropriate for highway-oriented business areas and space-consuming commercial uses. Higher coverage could be permitted for the more intensive development within the urban arterial business zones surrounding the central business district and regional shopping centers.

Building Height. Height limits of 35 feet are most common. These limits probably reflect those applicable to surrounding residential areas. By maintaining a uniform silhouette, the business uses appear less intrusive. Again, higher limits might be desirable in urban arterial business areas located in the more intensely developed parts of the community.

Yards. All the ordinances summarized in Table 6, with one exception, require front yards, the more common requirement being 50 feet. In most cases this area can be used for parking, except that several ordinances require that a 10-foot strip along the front lot line be landscaped.

Most of the ordinances require side and rear yards of 10 or more feet. They should be required to permit access between buildings, unless the structure is part of an integrated group of buildings. If the lot adjoins a residential area, additional yard space is required. Virtually all of the ordinances require adequate landscaping along the property line to protect adjoining residential areas.

The Santa Clara County ordinance, while not requiring side or rear yards, places the final decision in the hands of the planning commission.

Side and rear yards may be required by the Planning Commission through architectural and site approval in order to provide adequate light and air; assure sufficient distance between adjoining uses to minimize any incompatibility; and to promote excellence of development; except that, where a side or rear yard is provided, it shall be at least ten (10) feet wide.

Where a lot borders a residential area the county's 10-foot yard requirement is less than all but one of the other ordinances. However, the landscaping and screening standards are more stringent.

Where a lot ... sides or rears upon property in any R District, a yard at least ten (10) feet deep shall be provided. Any such yard shall be used and maintained only as a landscaped planting or screening strip except for accessways on which shall be placed hedges, evergreens, shrubbery, or other suitable planting or screening materials. A wall shall be located within such side or rear yards, not more than two feet from the property line, and not less than five feet nor more than eight feet in height.

Parking and Loading Areas. Arterial business uses depend on the single-purpose trip by automobile to the particular store. Parking requirements should be determined by individual store type, rather than by establishing a ratio of square feet of parking area to square feet of floor area applicable to all permitted uses in the district. The variety of business types precludes any such simple formula.

Off-street loading requirements for arterial businesses also seem to indicate that there have been few attempts to relate loading space needs to particular uses by adjusting loading facilities to the type of business activity.19 Requirements for many types of arterial business uses, however, are spelled out in the proposed Grayslake, Illinois, ordinance. At the other extreme, the Santa Clara County ordinance states that "The amount of space required for ... loading shall be established through architectural and site approval." While objections could be raised to either approach, both ordinances do recognize the diversity of loading space needs of arterial business types. Although the number of required spaces may vary greatly from ordinance to ordinance, there should be no disagreement on the desirable size of loading space. The National Industrial Zoning Committee recommends that berths be 14 feet wide and 55 to 60 feet deep, with an overhead clearance of 15 feet.20 Businesses accommodating city delivery trucks should provide berths 30 feet deep. A 60-foot apron or maneuvering area is recommended.

Access and Traffic Controls

This report has already discussed the importance of traffic control devices in ribbon commercial areas. The Santa Clara County ordinance contains several design standards for access control.

Access barrier. Each lot, with its buildings, other structures, and parking and loading areas, shall be physically separated from each adjoining highway or street by a curb or other suitable barrier against unchanneled motor vehicle ingress or egress. Such barrier shall be located at the edge of, or within, the ten-foot-deep yard along the lot line required by subsection 21-6.5 unless suitable curbs and gutters are provided within the highway or street right-of-way. Except for the accessways permitted below, such barrier shall be continuous for the entire length of any lot line adjoining a street or highway.

Accessways. Each lot shall have not more than two accessways to anyone street or highway, which shall comply with the following requirements:

- Width of accessway. The width of any accessway leading to or from a street or highway shall not exceed thirty-six (36) feet nor be less than fifteen (15) feet in width at the right-of-way line, The alignment of accessways and curb return dimensions shall be determined through architectural and site approval.

- Spacing of accessways. At its intersection with the lot line, no part of any accessway shall be nearer than twenty (20) feet to any other accessway on the same lot, nor shall any part of accessway be nearer than ten (10) feet to any side or rear property line at its intersection with a right-of-way line. Insofar as practicable, the use of common accessways by two or more permitted uses shall be encouraged in order to reduce the number and closeness of access points along highways. The fronting of commercial uses upon a marginal service street and not directly upon a public highway is also encouraged.

- Traffic hazards. The location and number of accessways shall be so arranged that they will reduce the possibilities of traffic hazards as much as possible.

The Springfield Township, Pennsylvania, ordinance (proposed 1959) imposes greater controls on groups of buildings to be constructed as an integrated development, requiring that all buildings front on a marginal street or similar area, and not directly on the major street or highway.

Special Entrance Districts

As the show window of the community, the appearance of the highway approach to a city is of special concern. The ordinances of two California jurisdictions — the city of Fremont and Santa Clara County — require architectural approval of all uses permitted in the highway business zone. Virtually all of the ordinances listed in Table 6 restrict the contents of advertising signs to the name of the establishment or products sold on the premises. The ordinances also control the number, size and placement of signs.

In 1961, St. Petersburg, Florida, amended its zoning ordinance to include a new district intended to improve the character of the gateway to the city along three major entrance streets. The Commercial Parkway District reflects the desires of local officials to create "a showcase atmosphere so necessary to our tourist economy."21

The district's use provisions differ from those in most highway commercial zones. Retail stores and service establishments, restaurants (but not drive-in eating places), personal service establishments, offices, hotels and motels, multiple-family dwellings with ten or more units, schools and mobile home courts are among the uses permitted. However, gasoline service stations and single-family residential uses are expressly prohibited. Groups of buildings or structures consisting of 10,000 square feet or more are permitted as special exceptions, and may be allowed by the zoning board of adjustment only after study and recommendation by the planning board.

Lot area and width and yard dimension requirements reflect an attempt to discourage building clutter common to many roadside areas. Minimum lot areas and widths as given in the ordinance are outlined in the Table 7.

(Download the PDF of this report from the link at top to see Table 7.)

To improve appearance from the road, only driveways and walkways are permitted within the front yards of principle structures. No part of a front yard adjacent to a street having a right-of-way of 100 feet or less can be used for parking, and the rear lines of these yards must be at least 100 feet from the centerline of the highway. Front yards adjacent to highways having rights-of-way in excess of 100 feet must be at least 50 feet in depth. The side and rear yard dimensions are 20 and 25 feet, respectively.

A different approach has been proposed in Charleston, South Carolina. An Entrance District has been suggested to overlay the general zoning district in which it is located. The overlay district would add to the provisions previously established for the lot or parcel of land. Strip areas 200 feet wide along nine major streets have been proposed to be included within the district. The dimensional requirements (yard, setback, and height) are not as stringent as those in the St. Petersburg ordinance, and the permitted use provisions are broader.

One of the basic problems in adopting a special entrance or gateway district is whether local officials can withstand the inevitable onslaught of requests for variances and rezoning. Land areas within this district probably will not develop as fast as roadside commercial areas within the less restrictive zoning districts. Consequently, pressures to relax entrance district zoning requirements are likely to be substantial.

Conclusions

It is necessary to revise past thinking by planners and other public officials on their reluctance to consider any kind of commercial zoning for new uses other than shopping center districts. Many urban arterial and highway service uses should be eliminated from the shopping center use list and provided for in other districts. Such a separation recognizes the basic principles of retail use compatibility.

The worst abuses of strip zoning can be mitigated or avoided entirely by careful drafting of the district provisions. As we increase our knowledge of what businesses can be grouped together most appropriately, the number of different commercial use districts will probably increase and the effectiveness of zoning controls will develop accordingly.

References

1. Locational Tendencies and Space Requirements of Retail Business in Suburban King County (Seattle: County Planning Department, 1963), p. 14.

2. Brian J. L. Berry and Allen Pred, Central Place Studies, A Bibliography of Theory and Applications (Philadelphia: Regional Science Research Institute, 1961), quoted in Locational Tendencies ... , op. cit., pp. 4–5.

3. William L. Garrison, Brian J. L. Berry, Duane F. Marble, John D. Nystuen and Richard L. Morrill, Studies of Highway Development and Geographic Change (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1959), p. 58. This volume contains reviews of many of the important works concerning the spatial structure of retail trade.

4. Brian J. L. Berry, "Ribbon Developments in the Urban Business Pattern," Annals of the American Association of Geographers, Vol. 49, June 1959, pp. 145–155.

5. Locational Tendencies ..., op. cit.

6. Ibid., p. 15.

7. Edgar Horwood and Ronald Boyce, Studies of the Central Business District and Urban Freeway Development (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1959).

8. Brian J. L. Berry, "Planning for Business Centers," Land Economics, Vol. 35, November 1959, p. 310.

9. Ibid.

10. Tulsa Metropolitan Area Comprehensive Plan (Tulsa, Oklahoma: Metropolitan Area Planning Commission, 1960), chap. 4, p. 5.

11. "The Plan for Commerce," Comprehensive Plan for the City of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: City Planning Commission, 1960) pp. 44–55.

12. Ibid., p. 54.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Route Eight Study — A Proposal for Highway Renewal (Pittsburgh: Regional Planning Association, 1959).

16. For additional discussion and examples, see Statements of Purpose and Intent in Zoning Ordinances, ASPO Planning Advisory Service Information Report No. 92, November 1956.

17. Zoning ordinances are identified in this report only by jurisdiction and year, with notations for proposed drafts or amendments. Subsequent references to the same ordinance are identified only by jurisdiction.

18. 1975 Metropolitan Tulsa Commercial Land Needs (Tulsa, Oklahoma: Metropolitan Area Planning Commission, 1959).

19. For a methodology used in estimating loading spaces, see Victor Gruen and Larry Smith, Shopping Towns U. S. A. (New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1960).

20. Principles of Off-Street Parking and Loading for Industry (Columbus, Ohio: National Industrial Zoning Committee, 1962).

21. Letter to ASPO Planning Advisory Service from John B. Harvey, Director of Planning, St. Petersburg, Florida, June 21, 1963.

Copyright, American Society of Planning Officials, 1963.