Apartments in the Suburbs

PAS Report 187

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 187 | June 1964 |

Apartments in the Suburbs

Download original report (pdf)

THE REPORT AT A GLANCE

Apartment building construction in recent years has captured an increasing portion of total housing starts, especially in the suburbs. High land costs and changing family composition are producing even more pressure for apartments in suburbs as well as in central cities. This report is directed toward helping local government officials review proposed apartment developments on the basis of effective regulations and standards.

The cost-revenue study is an important tool in measuring the effects of apartment developments from the standpoint of the net cost to the city government of providing services. Although cost-revenue studies have been developed for many years, there are still severe limitations on their usefulness. Too many studies have given inadequate attention to the cost per dwelling unit, the cost for the provision of schools, the economic effects of alternative land uses, and the hidden costs for providing for governmental services. Cost-revenue studies are invaluable, however, when carefully done with full appreciation of what they can — and cannot — accomplish.

Planning and zoning for apartments in the suburbs should be based not only on conventional standards but also on factors reflecting livability and the intensity of land use in relation to open space and other environmental amenities. Particularly important in meeting these goals are the latest land planning standards, known as "Land Use Intensity Ratings," that have been developed by the Federal Housing Administration. These standards are much more sophisticated and flexible than conventional zoning provisions and should be used in conjunction with zoning, subdivision regulations, and other land-development controls.

This report has been prepared jointly by the staffs of the American Society of Planning Officials and the International City Managers' Association for distribution as the June, 1964, report to the subscribers to their services — Planning Advisory Service of ASPO and Management Information Service of ICMA. Research for this report was handled by Frank S. So of the ASPO staff and Jerry B. Coffman and Walter L. Webb, respectively former staff member and staff member for ICMA.

INTRODUCTION

Within the past five years the proportion of apartments in the new housing being built in the United States has doubled. In 1959 multifamily homes accounted for somewhat less than 20 per cent of the housing units built that year. Currently, apartments constitute approximately 40 per cent of the nearly 1.6 million housing starts.

There are several reasons for the shift in housing construction away from the predominantly single-family pattern of the 50's. Probably chief among the reasons is the skyrocketing price of land available for residential construction. Figures issued by the Federal Housing Administration show that the cost of the improved lot under the average single-family house has approximately tripled between 1950 and 1963. Reports from the more rapidly growing metropolitan centers indicate that even this may be an underestimation of the situation. The experience of developers has been that the increased cost due to high land prices, added to the general increase in construction costs, has priced the single-family residence out of the reach of a large proportion of the potential buyers. If the land cost per dwelling unit can be cut by increasing the density of development, the builder can regain part of this lost market. The most direct way to reduce the cost of land per dwelling unit is to switch building from single-family homes to multifamily homes.

Another factor favoring an increase in apartment construction is the need to achieve a better balance between apartments and single-family houses. The mix of residential construction after the war was so skewed toward the single-family house that there was actually a shortage of modern apartments in most parts of the United States. While it is impossible to say precisely what a "proper" balance between single-family and multifamily units might be, there is reason to believe that the construction pattern of the 1950's was not producing it.

The latest episode in the changing drama of residential construction has been the pressure in metropolitan areas to increase the number of apartment buildings in suburbs. Here again, land costs have played an important part, shifting high-density construction away from its traditional location in the central city. Land costs in prime apartment building locations in central cities have been extremely high — so high, in fact, that all new apartments were either luxury apartments for high-income families, or small apartments for single persons and childless families (which, on the basis of rental cost per square foot, could also be classified as luxury apartments). In order to reach a larger market, the apartment developer has gone to the suburbs for cheaper land on which to build, hoping to produce apartments that would carry more modest rentals.

Still another reason for apartment building in the suburbs has been a newly created demand for apartments in such locations. The demand has come from older persons. These are persons whose families are raised, who are tired of keeping up a large house and yard, yet who want to stay in the same suburban area with their friends, their children and grandchildren.

The sudden increase of pressure for apartments in suburbs has brought about two difficult situations. First, there has been widespread reaction against apartments by the citizens of the suburbs. In some cases demonstrations against the proposals have been almost violent. Second, public officials and planning commissioners in the suburbs have not been prepared to judge the merits of arguments for and against apartments, and they have also not known what regulations and standards should be established to minimize the ill effects of apartments — if there actually are any ill effects.

This report is directed primarily toward helping public officials meet the second situation. However, a few words about the first problem — the antagonism toward apartments — should be included. Most often heard are three arguments:

- Public services to apartments are more heavily subsidized than are such services to single-family houses.

- Apartments attract an undesirable sort of people.

- Apartments depreciate property value in the neighborhood.

The first of these objections — that apartments do not pay their way as well as single-family houses — is one about which public officials would naturally like to know the truth. Universally, apartment house promoters claim the opposite, that apartments cost the public less than single-family houses. It is far from clear what is the truth, and the first part of this report discusses the studies that have been made and the problems inherent in such cost-benefit analyses.

The objection to the sort of people who might come to live in suburban apartments is an objection that rarely gets put in writing, but it is one that obviously motivates much of the antagonism toward apartments. There is a widespread belief that persons who rent housing are necessarily less desirable than persons who own their own homes. This is, of course, absurd.

Public hearings also show people tend to equate apartment buildings with tenements, to feel that all apartments are potential slums. With this notion of potential slum character, there goes the fear that the apartments will be occupied by members of a minority group. In fact, the fear of desegregation is one of the strongest factors contributing to the objections to apartments.

The fear that apartment buildings will depreciate the value of nearby single-family houses does have relevancy. However, it is possible to eliminate the depreciating effects of apartment buildings if the community has proper regulations and proper review of all proposed apartment building developments.

A most important regulation is a strong building code, effectively enforced. Too many apartment buildings erected in the past five years have not been well built. A most frequent criticism of new apartments has cited the lack of acoustic insulation between adjoining apartment units — paper-thin walls. Other legitimate criticisms have been made of poor interior design, inadequate parking facilities, and land crowding.

While this report does not discuss building codes, public officials must be certain that their own building code adequately protects the community from shoddy apartment construction. Suburban communities often get along with out-of-date codes, and particularly — since they have not faced the problem before — with out-of-date provisions for multifamily construction.

Unquestionably, much of the objection to apartment building in suburbs is emotional and unreasoning. Much of it is pure snobbery. Hopefully, public officials can approach the problem intelligently and logically. It is recognized that logic will not win over the die-hards, but it may persuade some of the more reasonable persons who are rightfully concerned. It is most important that the community be prepared to the best of its ability to minimize any ill effects that apartment buildings might have.

The first section of the report that follows is devoted to an analysis of the cost-revenue aspects of multifamily dwellings. The second section analyzes the planning and zoning problems presented by apartment building in the suburbs and makes suggestions on how to handle these problems.

SECTION I – COST-REVENUE ANALYSIS OF SUBURBAN APARTMENTS

The main research tool used to determine the net cost to the city of providing services to new apartment buildings is the cost-revenue study. Because of the popularity of this approach, municipal officials should be aware of basic techniques for cost-revenue analysis, typical studies of the desirability of apartment construction, and limitations of this approach. This section will present an overview of cost-revenue analysis applicable to apartments. Although it will not specifically suggest how to conduct a study, it will provide guidelines for using this approach.

Techniques and Limitations

The most comprehensive study available of cost-revenue analysis, Ruth L. Mace's Municipal Cost-Revenue Research in the United States, defines cost-revenue analysis as:

... research into the net cost to a governmental unit of providing municipal-type services to a specific area. Net cost is the difference between governmental expenditures, which may be specifically identified with a particular area, and the revenues that will come to the governmental unit from that area or by virtue of the characteristics of that area. Area, in the above context, means land. It can take in a whole governmental unit, or some part of a governmental unit, including a neighborhood, a category of land use, or a single dwelling unit.

The methods used in cost-revenue analysis vary widely depending upon the specific nature of the studies, the research resources available, and the time demands. In each study, an attempt is made to develop unit measurements of cost and revenues as applied to specific services. These measurements are then used to evaluate the net gain or loss that might be anticipated by adding those services or extending them into different geographical areas.

The most common approach in cost analysis allocates the total cost of individual functions among areas or uses on the assumption that the costs of service will vary with one or more factors, such as property valuation, area, number of properties, structures, or dwelling units. As an example, a department operation involving $50,000 in expenditures per year might cost 25 cents per $100 of assessed valuation on the basis of a total assessment of $20 million in the community. New homes assessed at $12,000 in an area considered for annexation would therefore each cost $30 per year to service in this department. Revenue anticipations are commonly estimated on the same general basis, but with greater accuracy in the case of services for which there are direct service fees or charges.

Some cost analyses involve more complicated and others more simple methods than the above approach. The most complex is the use of performance budgeting techniques by which units of measurement are devised from detailed studies of actual performance records. The simplest method is to base the incremental cost estimates on the judgment of department heads.

In practice, these different approaches are likely to result in fairly wide variations in findings. Indeed, differences have been so considerable that some officials have taken a dim view of cost-revenue studies, maintaining that even the most detailed research can involve "swallowing of many camels while straining at many gnats." There is some merit to this criticism. Not only do different techniques often produce different results, but the formulas do not always take into account many other factors that sharply affect the findings.

Mrs. Mace has suggested three basic limitations to cost-revenue analysis. Although specific criticisms of individual studies will be presented later, the following general limitations should be kept in mind at the outset:

- The cost-revenue relationship presents only a partial picture of the net costs of development of various types. It usually is concerned only with direct municipal costs and revenues, while indirect costs and revenues may be equally or more significant to local governments.

- Cost-revenue analysis is meaningful only if it is developed with and takes into account a whole range of basic information. For example, many studies do not recognize the economic interdependence of the municipality and the region in which it is located. Land uses cannot be encouraged or discouraged simply on the basis of policies tailored to local tax needs. The metropolitan or regional demand-and-supply situation must be taken into account. Findings of cost-revenue studies must therefore be evaluated in terms of broad forces with which the typical limited study usually is not concerned.

- Cost-revenue analysis is an expensive, time-consuming, and complicated process. Moreover, such research is not a "one-shot" job. Service costs, revenue structure, municipal policy, economic conditions, and the tax base are ever-changing variables which make it mandatory that restudy take place at regular intervals.

Recent Cost-Revenue Studies

Below are discussed the basic techniques and conclusions of three recent studies on the cost-revenue aspects of apartments in the suburbs. The purpose here is not only to acquaint municipal officials with techniques employed but also to provide a base for evaluating the worth of these studies. After outlining the studies, a section is presented on questions that might be raised about methods employed.

Philadelphia Study. In October, 1961, a study of high-rent apartments in Philadelphia suburbs was prepared by Anshel Melamed.1 The basic technique employed by Melamed was computation of tax potential of apartment developments, on a per-acre basis, in relation to tax potential of other land uses. By employing this technique, the study showed that no other land use exceeded the tax potential of apartments. Although the suburban apartment developments were built at densities far below central-city averages, market value per acre was as high as or higher than any other land use.

The actual income from various land uses was used to show the extent to which high-rise, high-rent apartments strengthened the tax base: Property tax revenue for high-rise apartments was compared with that from a steel fabricating plant, a research laboratory, a shopping center, and a motel. From this analysis, the study showed high-rise apartments produced the second highest gross tax revenue and a per acre revenue of $7,300, more than double the next highest use.

On the expenditure side, Melamed suggested that apartments show up quite favorably in their limited requirements for public services. Of key importance, the study noted, is the small number of school-age children in such units. Interviews showed that only 7 per cent of the apartments were occupied by householders with children. In none of the high-rental suburban apartment developments were there more than 10 school-age children per 100 dwelling units. This compared with an average of upwards of 50 children per 100 single-family suburban dwellings. Since school taxes represented as much as 60 per cent of the total municipal levy in the suburban areas, the study concluded that the relatively low number of school-age children in apartments represented a great savings to the municipality. The actual education cost per apartment unit, however, was not calculated.

The second major reason why apartments produced relatively low municipal costs was that they had limited requirements for public services. The study noted that such services as police and fire protection, trash collection and disposal, highway maintenance, and lighting "are surely less costly to provide" for apartments than for other uses. Again, however, no actual cost figures were calculated.

Stamford, Connecticut, Study. This study,2 conducted by Dominic Del Guidice in 1963, was concerned with one basic question: Does that portion of high-rise apartment property tax revenues allocable to education offset the local share of educational costs which results from those apartments? The answer submitted was "Yes." The study concluded that each of the dwelling units in the four high-rise apartments in Stamford produced a "surplus" of $33.34 per year. That is, the apartments produced this much more education revenue per year than they required of municipal outlay for educating the children in these apartments.

In order to use actual expenditures rather than appropriations, the last completed fiscal period for which data were available was selected for study. In addition, state aid to education was subtracted to obtain the net cost of education to the municipality and then compare this to the tax revenues derived locally. Since the concern was primarily with the current situation, the educational share of previous debt service was not charged to education.

As noted in the Philadelphia study, Del Guidice observed that the high-rise apartment revenue "surplus" results because apartments have relatively few school-age children. On a city-wide basis, the study showed that two dwelling units were required to produce one public school child, but it took 7.6 apartment units to produce one public school child. The study further showed that older apartments produced even fewer school-age children.

Although the study offered no statistical calculations, it stated that if costs other than education were analyzed and compared to total tax revenues, high-rise apartments would be even more advantageous. This was because apartments "permit many municipal services to be provided in a concentrated manner."

The study conceded that high-rise apartment assessments and property taxes per dwelling unit were less than for the average single-family residence. This was more than offset, however, by the low educational costs of apartments. Again no comparative figures were computed, but Del Guidice concluded that residential uses as a whole do not "pay their way," while the "surplus" from apartments results from low education costs.

Prince George's County, Maryland, Study. The most comprehensive recent cost-revenue study of apartments was conducted by the Economic Development Committee of Prince George's County, Maryland, in 1963.3 A broad-gauged study of business and one- and two-family dwellings as well as of apartments, the study compared income and expense for the county plus federal and state contributions. The particular strength of this study in relation to the other two is that direct cost-revenue comparisons were possible between apartment units and residential dwelling units. This is important because, in studies of whether to build apartments, the usual alternative is to use the land for single-family dwellings.

Although the study showed that total income from all sources per residential dwelling unit was greater than from apartment units, the total costs per dwelling unit were more than twice those of apartment units. The net outcome, therefore, was that apartments brought a yearly $134.29 "surplus" per unit; residential dwellings brought a $167.24 "deficit" per unit. As in the other studies, the basic savings from apartments came from reduced education costs resulting from fewer school-age children.

One- and two-family dwelling units produced an average of .943 pupils per unit; apartments produced an average of only .242 pupils per unit. Thus, while the average education cost per unit for dwellings was $504.50, the cost per apartment unit was only $124.97. Costs of all other services per unit were calculated at the same figure for both dwelling units and apartment units. Education was thus the only cost on which it was possible to show differences in expense.

As final calculations showed, the average one- and two-family dwelling unit did not even pay the direct cost to the county to educate one child. At the same time, however, apartment units more than paid their way for all services, providing a surplus to help defray the cost of residential dwelling units. Although again not offering actual figures, the study suggested that if other costs had been allocated in proportion to use of government services, apartments would have come out even better.

Evaluation of Cost-Revenue Analysis

The three studies outlined above provide a base from which to evaluate cost-revenue research applied to apartments. Below are discussed two fallacies that indicate the fundamental flaws in these studies. Next is presented a discussion of dangers to avoid in making a cost-revenue study. The purpose here is not to discourage use of cost-revenue analysis; rather it is to point out pitfalls that hopefully can be avoided when one is aware of them.4

Questioning the Studies. Although an expert could point up numerous weaknesses in each of the studies, the prime defects might be labeled as the "per-acre fallacy" and the "nonschool costs fallacy." Each of these defects is discussed below.

1. The Per-Acre Fallacy. In the first study noted, concerned with high-rise, high-rent apartments in Philadelphia, all estimates of potential revenue were calculated on a per-acre basis. Thus it was shown that on this basis potential revenues from apartments exceeded that obtainable through other land uses. But acres of land do not demand school, local, or county services; the family units living in apartments demand these services. A more accurate basis on which to make calculations is costs and revenues per apartment unit.The weakness of per-acre calculations is illustrated by comparing the revenue findings of the Philadelphia study with those of the other two studies. In each of the other studies, which calculated tax returns on a per-dwelling basis, apartment-tax revenues were much below those of single-family dwellings. The much smaller proportion of tax revenue from each apartment unit usually has a more significant effect on single-family home taxes than does the greater amount of taxes per acre yielded by apartments.

It should also be noted that, to be consistent, the number of school children per acre in apartments should be used in a study that calculates tax revenues on a per-acre basis. If this were done, the obvious result would be a much greater number of school-age children per acre in apartments than in single-family dwellings. In fact, opponents of apartment buildings often make a strong point of this issue. They argue that the greater number of school-age children per acre in apartments creates needs for classrooms and other school facilities beyond that required by constructing single-family dwellings on the same land.

2. Nonschool Costs Fallacy. Each of the studies claims that apartments reduce nonschool municipal costs, but none attempts to prove this. The studies generalize that it seems logical that services provided to a concentrated group of people will cost less than if provided to single-family dwellings. But the mere fact that one, ten, or one hundred families live under one roof has no causal relation to the incidence of crime, fire, or unemployment. Some studies have shown that costs per family unit for both homes and apartments are relatively constant for such common services as snow plowing, traffic lights, shade trees, parks, recreation facilities, libraries, fire protection, police protection, welfare, health, and other basic municipal services. At any rate, it is unconvincing to imply, without evidence, that apartment nonschool costs are less than for single-family dwellings.Also to be considered is the need for new facilities caused by restructuring land to serve higher densities. Often, for example, construction of apartments means that the community must enlarge existing sewer trunk lines, sewage treatment plants, and water lines. Sometimes even patterns of streets, highways, parks, and schools must be expanded to meet the needs of a new apartment building. This means heavy costs that often are not covered by tax revenues from apartments.

Dangers to Avoid. The following is a list of major pitfalls cited in recent literature on cost-revenue studies. In many cases it may not be possible to avoid all of these dangers, but at least they should be kept in mind as the results of a study are analyzed.

1. Realistic Development Alternatives. It does little good to compare the costs and revenues expected from a proposed apartment development with some other alternative that has almost no chance of being built on that site. Most apartment sites would return more government revenue relative to cost if they were developed for commercial or industrial use or as a site for $80,000 homes. But if there is no market for such structures at the site, the comparison is irrelevant. Thus comparisons must be limited to uses and structures which could be sold or occupied if built on the same site.Ideally, studies should proceed by a case approach in which new apartment developments are matched with single-family developments of the type that probably would have been built if the zoning had remained single-family. Only by this procedure is it possible to compare realistic alternatives.

2. Hidden Costs. The actual expenditure picture must take into account indirect and nonmonetary costs as well as costs easily ascertained from municipal services provided. For example, numerous apartment dwellings can diminish the number of single-family homes that do not have children in school. Since this type of home pays a great deal more than the cost of municipal services it demands, tax revenues relative to costs are greatly increased by having as many of these homes as possible. Tax losses from displaced residents and changes in land use are examples of other indirect costs that sometimes result when an apartment is constructed. Indeed, one study has suggested that tax revenue from apartment units will average less than one-half the tax revenue received from every family unit that previously lived in a single-family home on the same land.Nonmonetary costs of apartment buildings might include decline of the "character of the community," decreased civic interest, and other such costs not easily ascertained or obvious. Often fears of the "type" of people an apartment development will bring into the community are of as great importance as direct costs cited in cost-revenue studies.

3. Predetermined Conclusions. It is unfortunate but true that many suburban cost-revenue studies are undertaken to make a case for a predetermined course of action. They are designed to provide a scientific basis for discouraging low- and medium-priced residential uses. Ruth Mace, whose Municipal Cost-Revenue Research in the United States was cited earlier, has commented, "Regardless of whether or not their objectives are desirable, most of these ‘propaganda' studies are characterized by a lack of objectivity, short-cut methods, and conclusions that invariably agree with initial hypotheses." In other words, anything can be proved with statistics. It is therefore important not to begin a study already knowing what one wishes to prove.

4. Considering Local Conditions. A fourth pitfall in cost-revenue analysis is application of the findings of one report to the conditions of a completely different community. As noted above, a cost-revenue study can be used to show whatever its user wants to prove. Thus, it is easy enough to find a study that will support conclusions one wishes to sell. But the basic fallacy in this is that local conditions must be considered.In addition, one must be careful not to let prior studies, even of his own community, influence new studies of apartment dwellings. For example, the number of school-age children per apartment dwelling presently in the city may not remain the same with the construction of new apartments. This number can vary depending on such factors as the cultural tradition of the population that will use the facility, rent levels, provision for yards, and the quality of the neighborhood school system. A study should not lose its objectivity by being too greatly influenced by past studies.

5. Incomplete Analysis. Possibly the greatest pitfall in cost-revenue studies is superficial analysis. In the studies noted earlier, for example, none presented statistical analysis of nonschool costs. Each study, in a broad generalization, suggested that these costs would be less for apartment units than for residential dwelling units. Although it is commendable that the studies at least mentioned this aspect of the problem, each was quite deficient in analysis of conclusions on this point. Such incomplete analysis is widely typical and is probably the main reason for such varied conclusions about whether apartments pay their way

In addition to incomplete analysis, the cost-revenue analyst must beware of inadequate information from which to analyze. Often figures are not available for similar periods of time, and thus conclusions are unreliable. With many studies the major problem is getting the raw data for study. Of the studies noted in this section, only the Prince George's County study had available full information for the same period, by county, state, and federal agencies. Obviously, results are meaningless unless the raw data from which they are obtained are accurate and usable for comparisons.

As noted at the outset of this section, weaknesses and limitations of cost-revenue analysis have been cited to warn municipal officials of dangers involved. But this is not to imply that cost-revenue analysis is unusable or useless. It is, after all, the best method yet devised for estimating whether apartment construction will be worth the costs involved. But in view of the crudeness of many of its techniques, the method must be used with caution. Techniques are constantly being improved, particularly as a result of some good work at colleges and universities. As more municipal records are processed by machines (particularly the new computers), more and better data will become available.

SECTION II — PLANNING AND ZONING FOR SUBURBAN APARTMENTS

There is no single source to which the planner or public official in a suburban community can turn to find detailed standards for apartments. The kinds of questions that need to be answered include: Where in the city should apartment buildings be located? What is the proper density? What site planning standards should be set? How many apartments should be permitted? The little bit of information that might help answer these questions is scattered throughout planning and architectural literature. This report consolidates much of this material. In addition, sources discussing high density projects, usually in central city locations, are useful. While such projects are unlikely to be built in outlying areas, the principles and generalizations developed in these studies are still largely applicable in most suburbs.

This section of the report will proceed from a discussion of location principles, to density and site planning standards (with emphasis on the Federal Housing Administration's new minimum property standards), and finally to examples of handling apartments in the zoning ordinance.

The factors entering into selection of the approximate location for apartment buildings are varied. They range from the economics of land use to local public opinion and must be considered singly and in their relationship to one another. The discussion here relies heavily on excellent planning agency reports from Denver, Colorado, and Santa Ana, California.5 Although neither of these reports deals specifically with suburbs, each treats multifamily development in a way that can be used as a framework for broader generalizations.

Land Value and Market Factors

In every suburban community the land in certain areas is more valuable than in other areas because of location factors. Typical of this is land near highway interchanges, mass transit stations, or shopping centers, and land fronting on major streets. Such land is often held back from development by owners hoping for increased value and more intensive use in the future. Large scale subdividers often leave a corner property for that shopping center that never quite materializes. Land owners along the major highway into the suburb hold out for years, waiting for the right opportunity. Eventually, rising taxes force the owners to do something. The market for commercial land may not be good and the local city council may have a policy against more commercial development. Or in the older inner suburb, groups of lots may have been vacant for years. Perhaps a few of the oldest houses can be torn down if an economic reuse (at a greater density) is feasible. In some cases there may be some vacant land left near the town's planned industrial center. The industry is as safe, clean, and noise-free as possible, yet single-family houses might not sell. The owners or developers in these situations, looking for the best prices or good investments, turn to the apartment building.

Apartment construction may not be suitable in all of the above situations and certainly zoning should not be based only on the pattern of land values, particularly when the value is based on hope rather than adequate economic justification. However, land economics plays a strong role in influencing land use controls — particularly in pressures to change zoning districts to more intensive uses.

The market for apartments is another important factor that will influence local development policies. The growth in demand for apartments and the number of apartments built to satisfy the demand are well known. The frequent requests of suburban officials for information is the basic reason for publication of this report. Yet there also seems to be great reluctance on the part of officials and citizens in many suburban communities to recognize the growth in and popularity of this type of housing.

Officials of each suburban community should be aware of the housing market forces that will influence the community's growth. Of course, it will be an unusual suburb that has a planning department capable of preparing a special analysis of the market for apartments. It will be desirable to watch metropolitan economic and construction indicators (sometimes prepared by metropolitan planning agencies, or by financial and mortgage institutions) in order to assess the effect of metropolitan changes on the community. In some cases it might be wise to hire a consultant to prepare a housing and growth forecast. Or a community may have had such a study prepared in conjunction with a comprehensive plan. In other cases, when a developer proposes to build a great number of apartments in the community, he can be required to submit a market analysis similar to that required in many communities for shopping center developments.

Site Factors

High density housing normally requires reasonably level topography. However, an unusual site may be effectively developed with the planning of a landscape architect and a skilled architect. There are a number of highly regarded California and European examples of apartment buildings constructed on particularly rough or wooded sites. Suitable soil conditions are necessary, because apartment buildings need soils with more than average load-bearing capacities. Local soil surveys should be checked or on-site tests made to guard against unstable soil and subsoil conditions.

Public Services and Facilities

While most officials and citizens have been concerned with the relationship between apartments and school budgets and enrollments, far less attention has been given to provision of other public services and facilities. Apartments must be located where adequate public water and sewer facilities are available. Apartment densities demand the full range of urban utility services — sanitary and storm sewers and public water supply. Usually, no problems are connected with the provision of utilities such as gas, electric, and telephone service. Adequate garbage and refuse disposal services must be available. Police and fire protection must also be adequate. Of particular importance is the adequacy of fire fighting equipment for any high-rise buildings that might be permitted.

Increased population densities also mean increased traffic generation. Because of this, apartments should be located on major streets and collectors and should not be placed where they funnel large amounts of traffic through single-family neighborhoods. A large apartment development may actually create additional costs for widened streets and traffic control devices. Space for off-street parking facilities is absolutely essential.

Another important consideration is recreation and park facilities. Apartment developments may provide on-site recreation facilities such as swimming pools or tennis courts. However, the demand for facilities will not be limited only to the site. The municipality should expect a demand for additional facilities commensurate with the age, family composition, income, leisure time, and tastes of the population that will live in apartments.

In short, more intensive urban services will be needed for apartment areas than may normally be necessary for the typical low density single-family areas of suburbs. Such services and facilities should already be available or, if not, the community must plan to provide them.

Other Factors. A location principle, repeated more often than any other, is that apartments should be near major transportation facilities. The availability of mass transit facilities is important to the suburban apartment developer since his tenants are likely to be commuters — where facilities are available — to as great an extent as residents of single-family dwellings, if not greater. High density development near mass transit stations, therefore, is desirable. Whether or not the metropolitan area is served by mass transit facilities, locations on major streets and highways and near expressway interchanges will prevent the added traffic from passing through intervening lower density residential neighborhoods.

To provide an economic use for land that has not proved salable for single-family dwellings, the community may permit apartments in locations close to the suburb's major business district (in an older suburb) or on the periphery of a shopping center.

The use of apartments as a transitional use or buffer in these areas, however, should be approached with caution. Too many public officials assume that apartment developments are appropriate to buffer single-family neighborhoods from undesirable dirt, noise, light, and glare of commercial and industrial areas. This belief stems from the outdated idea of "ranking" uses and zoning districts on a "more" or "less" restricted" scale. Single-family districts were "most" restricted; industrial districts were "least" restricted. Too often what happens is simply that a greater number of people are exposed to the same undesirable conditions. The use of apartments as buffers is not only ineffective, it is also a continuation of the "second-class citizen" attitude mentioned in the introduction to this report. Compatibility of uses in zoning should be the governing principle and such factors as property values, traffic conflict, mixture of pedestrian and vehicle movement, aesthetic considerations, psychological factors, and building height and bulk must be carefully evaluated in order to select the proper location for multifamily dwellings.

Nearness to schools is another important location factor. Apartments with two or three bedrooms will house families with school-age children. The multifamily development should be within walking distance of schools to avoid excessive bus transportation costs. Where areas next to schools are proposed for apartment development, two land planning principles apply: Apartments should be sited to capitalize on the use of school playfields as open space; and the street pattern should be designed to minimize conflicts between school pedestrian traffic and vehicular traffic generated by the apartment buildings.

Areas adjacent to public open space are usually excellent locations for apartments. Any undesirable effects of higher density developments on adjacent single-family dwellings, whether real or imagined, will be lessened at such developments.

The siting of the apartment structure on the lot and building design may influence location. Although a project may satisfy other location principles, the development may not blend into neighborhood and community. Of particular importance is the compatibility with surrounding residential areas. Compatibility involves many things. In the words of one planning agency report it involves:6

.... occupancy composition of the proposed apartments, traffic generated by the development on surrounding streets, structural types and residential densities in relation to surrounding land use, orientation of buildings and site planning, and the planning of streets and lots in and adjacent to the area. High density apartments on an adequate site with proper site planning may be a good neighbor to a low density residential area while the standard brick box frequently seen in Denver apartment areas making maximum utilization of a small site may adversely affect nearby residential areas.

Another and quite important location factor is local public opinion. The question of permitting any apartments in the community has been highly controversial in many suburbs. Even if this issue is resolved in favor of permitting apartments, public opinion will still influence locations within the community. The cry will often be heard: "On the other side of town is okay, but this neighborhood has a special character [single-family] that needs to be preserved." Community officials cannot ignore public opinion in designating apartment locations. There are no standards on how much weight to give a public outcry against apartments, other than the good judgment of the officials themselves.

Apartment Standards: The Influence of FHA

In revising its land planning standards for residential development in 1963, the Federal Housing Administration introduced a sophisticated and flexible set of regulations using the concept of "land use intensity ratings." These new regulations will have considerable influence on local land use controls, particularly in planning for multifamily dwellings.

Bench Marks of Livability

Before analyzing the new FHA standards, however, it is useful to summarize another FHA publication, Intensity of Development and Livability of Multi-Family Housing Projects, by Robert D. Katz.7 In this excellent study, Katz studied selected high-rise and central city apartment projects in Europe and the United States. His generalizations about site planning also apply to the lower density development taking place in American suburbs.

Much of the opposition to apartments in suburban areas is probably due to the deplorable quality of building and site design of far too many projects constructed in the last few years. The identification of 12 aspects of quality and livability by Katz ought to be considered by local officials developing land use controls and in reviewing plans for apartment projects. The site planning elements are not so exact that a checklist can be constructed, but they can be used as general guidelines to judge some of the qualitative aspects of apartment projects:

Aspects of Quality and Livability in Multifamily Housing Developments

- Privacy

- Usable open space

- Individuality

- Diversity of housing types

- Location

- Proximity to community facilities

- Safety and health

- Circulation

- Automobile storage

- Blending of new housing into its surroundings

- Site details

- Views from and to a site

1. Privacy is often difficult to achieve in apartment developments, yet if it is present, the quality of the environment improves considerably. Site planning techniques for privacy include the use of screen walls or heavy landscaping to create private outdoor spaces. Buildings may be sited facing a court, or have wings jutting out to create private patios.

2. Related to the need for privacy is the provision of adequate usable open space for outdoor activities. Such space does not include parking areas or narrow sideyards. Areas for both active and passive recreation should be provided to match the age characteristics of the apartment dwellers.

3. Individuality of the buildings in the project can be achieved by different external materials, colors, landscape elements, and other design details. For example, row houses or garden apartments, set off from each other structurally, may also vary in color or materials. Providing small private yards for each dwelling unit creates another feature that gives individuality. Mixtures of low and high buildings and the use of staggered setbacks and broken roof lines can also be used to provide variety.

4. Diversity of housing types is closely related to individuality. While many suburbanites still believe that the intrusion of apartments into a single-family neighborhood will disrupt the area and depreciate property values, such mixtures have been deliberately planned by some developers of large scale projects. A portion of the project might contain single-family dwellings, another part might be set aside for garden apartments, and still another might include a medium or high rise building, with even a shopping center worked into the design. Such mixed-type developments, incidentally, have proved very successful — even more successful than most single-type projects.

5–7. Location, proximity to community facilities, and safety and health have already been discussed more fully in a previous section of this report. Too many municipalities still zone only those areas for apartments that are left-over parcels, unsuited for lower density development. In effect, a greater number of people per acre are forced to live in the poorest locations for high-density housing. Not only is housing quality usually lower from the very start in such circumstances, but an area of incipient blight is being created.

8,9. Circulation and automobile storage are related problems and in turn determine the type and usefulness of open space in a development. Ample parking should be provided, of course. However, massive parking lots should not be allowed to dominate the site or to split yard space into unusable bits and pieces. If at all possible, parking areas should be physically or visually separated by fencing, walls, landscaping, or changes in level. Pedestrian access should be provided to front and rear building exits and sidewalks should be separated from parking areas, access drives, and delivery entrances.

10. The blending of new apartment structures will not normally present problems in suburbs, except in older inlying cities that are experiencing development on bypassed lots, large or deep lots, or in some cases where older houses are being replaced by single apartment buildings.

11. Site details will be as important in a suburban location as in a city. Imaginative use of lighting, paving, landscaping, and building facades will add significantly to the quality of multifamily housing. Terraces, development around a swimming pool or other recreation area, and provision of imaginative playground equipment and play sculpture also increase attractiveness.

12. In the suburban landscape views to and from the site of most apartment dwellers are limited to the site itself unless they live in tall buildings. The tenants are more likely to be looking at an industrial or highway strip commercial development than will the single-family dweller in the same community. This is one result of a zoning policy that permits apartments only adjacent to commercial and industrial areas. As this report has previously emphasized, it is not proper to situate apartments near the worst areas of the community.

Perhaps more important to the suburbanite (and to the suburban official trying to make the decision) is the view from the single-family home or the street to the new apartment area. The Denver quotation concerning box-like structures will be heard often, whether justified or not. However, the proper blending of apartment buildings into the hitherto single-family landscape of suburbia is important and needs careful consideration (which probably means careful review of site and architectural plans) by local planning authorities.

Federal Housing Administration Land Use Intensity Ratings

The new standards of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) for residential development are more complicated than most existing zoning ordinance provisions for multifamily dwellings, but they may be understood with a little study. Planners and public officials should examine the new standards closely in drafting and administering local land use controls. Because many persons believe that the new system may revolutionize zoning, a full exposition is given. The standards cover more environmental and site planning elements than will be found in zoning ordinances, and they allow far more flexibility in site layout and in mixing housing types. Thus, they provide a sophisticated planning tool in evaluating requirements for apartments in the suburbs.

The following presents a brief review of some of the basic elements of control for apartments, the specific objectives of the new FHA standards, and how they differ from traditional zoning controls.

Traditional Zoning. The typical suburban zoning ordinance provides for residential districts differing from each other in density and in type of residence permitted (single-family, two-family, multiple-family). Mixtures of structural types at the same density are rarely permitted (although advocated by many experts) except for the cumulative effect of allowing single-family uses in two-family and multiple-family districts. Density is expressed in minimum lot area per family or dwelling unit, or by merely a statement of number of dwelling units permitted per acre. Occasionally, density is based on a room or bedroom count. For example, minimum lot area for one bedroom is set at 1,000 square feet; for two bedrooms, 1,500 square feet; and for three or more bedrooms, 2,000 square feet. Thus, the actual density expressed in dwelling units will vary depending upon the size of apartment units constructed on a particular site.

Some ordinances also regulate density and bulk through the use of floor area ratio standards. Height; building coverage; rear, front, and side yards are customarily regulated, as is the space between buildings. Parking requirements are also common. Less common are requirements for usable open space, even though open space (in addition to factors related to density) is perhaps the major element in residential environment that makes it pleasant, comfortable, safe, healthful, and desirable.

Basic Concept of FHA Standards. In almost all cases these zoning requirements are related to land area. The FHA standards, however, are based primarily upon floor area. In addition, most of the FHA standards are expressed in terms of ratios to floor area, rather than absolute dimensions. How does the land use intensity system work? This concept is best introduced by an example of the use of the Land Use Intensity Standards chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1 — Land Use Intensity Standards

A land use intensity rating between the 0.0 and 8.0, assigned by FHA to a particular site, is based on character of the neighborhood and community. In Figure 1 this rating appears on the horizontal axis and is read off at the bottom of the chart. The ratios permitted on the site are then determined by checking along the vertical axis representing the assigned land intensity use rating until that line intersects each of the curves, then reading off the ratio on the vertical scale, indicated along the left margin.

For example, suppose that the rating of a particular site is 5.0. Reading the figures off in order, from the lowest to the highest, the applicable ratios will be:

| Minimum recreation space ratio | 0.13 |

| Maximum floor area ratio | 0.4 |

| Minimum occupant car ratio | 1.1 |

| Minimum living space ratio | 1.1 |

| Minimum total car ratio | 1.25 |

| Minimum open space ratio | 1.8 |

Land use intensity rating correlates land area, floor area, open space, livability open space, recreation space, parking requirements, types of structures, and a range of densities. Definitions of some of the terms used are as follows:

Floor Area (FA) is the sum of the areas for residential use on the several floors of a building or buildings, measured from the faces of the exterior walls.

Land Area (LA) is the site area for residential use within the property lines, plus half of abutting street row, plus half of any abutting permanent open space (with certain limitations).

Open Space (OS) is the total horizontal area of all uncovered open spaces plus one half of the total horizontal area of covered open spaces (e.g., roofed porches, carports).

Livability Open Space (LOS) is the open space, minus the car area within the uncovered open space, minus one half of any covered car space that was previously eligible and credited in part to open space.

These are simplified definitions and the actual regulations, which are contained in the draft of Land Planning Bulletin No. 7 (to be published in 1964 by FHA), should be examined for all the exceptions, partial credits, and definitions of what can be counted on roofs, porches, or balconies.

The regulations also give definitions for the various ratios. Thus, there is a definition for open space and another for open space ratio. The floor area ratio is based on land area, the car ratios on number of dwelling units; all the other ratios are based on floor area.

The most critical step in using the land use intensity ratings is the actual assignment of a specific rating to the property where the project will be built. Once this is done, building and site requirements fall into place.

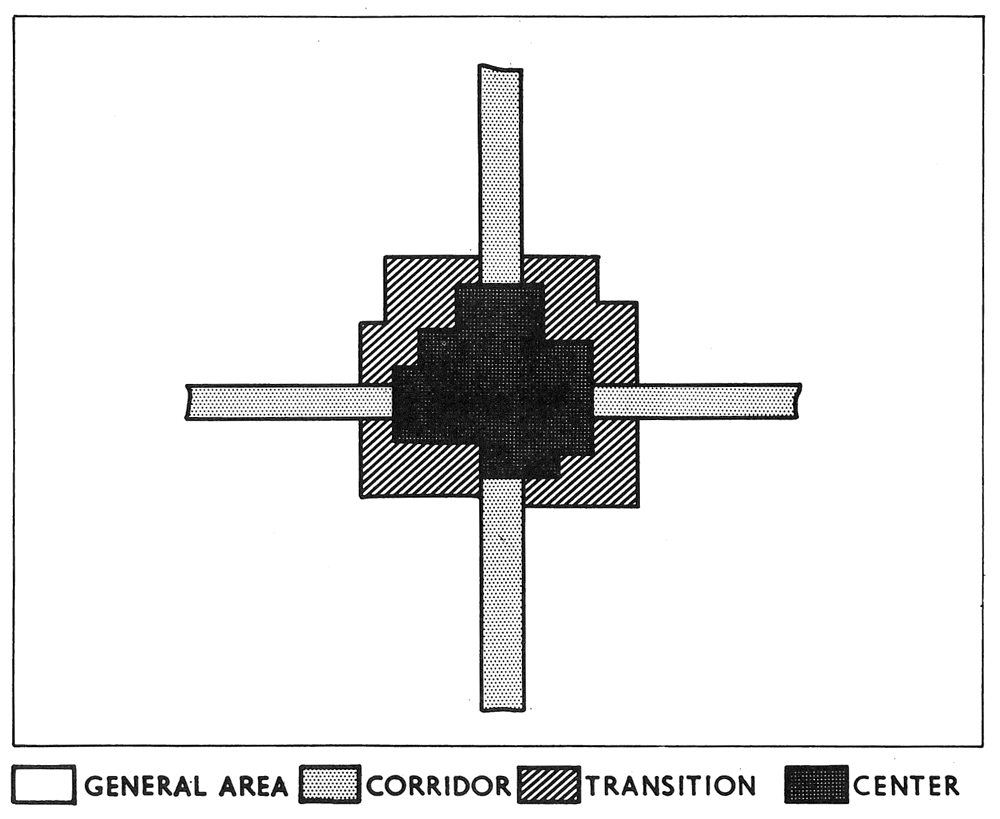

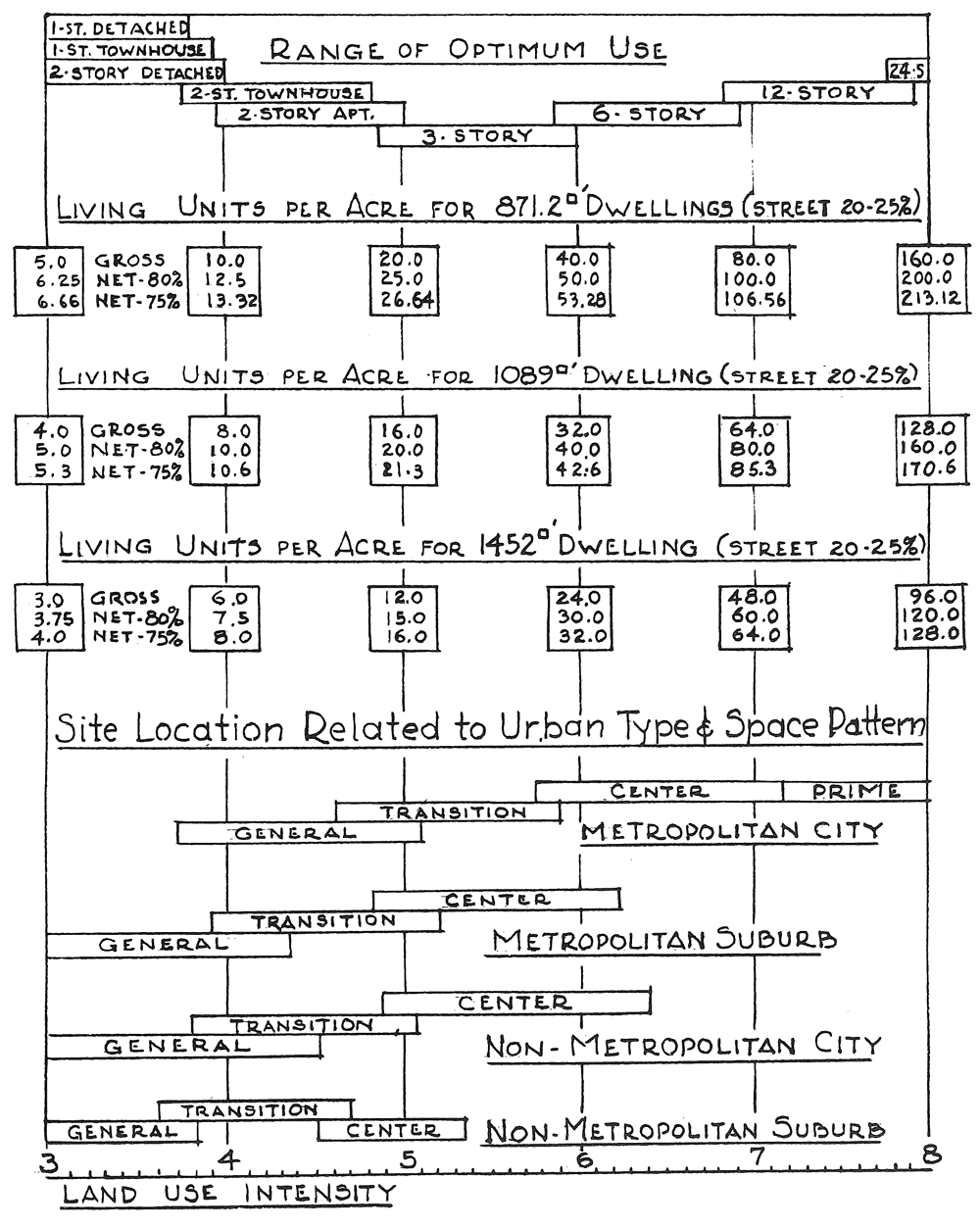

Application of Intensity Ratings. Because of the importance of the system, it is well to understand some of the basic ideas that make up the rating system and the process of determining the rating of a particular housing site. One purpose of the ratings is to ensure that new residential building developments will fit into the particular type of community as well as into the specific neighborhood within the community. Figure 2 is a theoretical illustration of a typical community building and land use pattern. Intensities (indicated by the density of shading) are greatest at the center, taper off in the transition and corridor areas, and finally level off in the outlying area. In Figure 3 the bottom portion shows the range of intensities that FHA feels is suitable for various types of communities as well as general locations within them. Present and anticipated land use patterns in the community presumably play a heavy role in FHA's determinations, as do land market factors. FHA is interested in preventing either too great or too low intensities in particular locations. A low intensity rating can adversely affect the project through underuse of the land. Similarly, a rating that is too high can lower livability, and in turn lower the potential rental or sale value of the property.

Figure 2 — Typical Community Pattern

Figure 3

Table 1. Land Use Intensity Related to Floor Area and Density

| Land Use Intensity (LIR) | Floor Area Ratio (FAR) | Floor Area (sq. ft.) per Gross Acre | Density in Land Use per Gross Acre | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1089 s.f./L.U. | 871.2 s.f./L.U. | |||

| 0.0 | .0125 | 544.5 | .5 | .625 |

| 1.0 | .025 | 1089 | 1.0 | 1.25 |

| 2.0 | .05 | 2178 | 2.0 | 2.5 |

| 3.0 | 0.1 | 4356 | 4.0 | 5.0 |

| 4.0 | 0.2 | 8712 | 8.0 | 10.0 |

| 5.0 | 0.4 | 17424 | 16.0 | 20.0 |

| 6.0 | 0.8 | 34848 | 32.0 | 40.0 |

| 7.0 | 1.6 | 69696 | 64.0 | 80.0 |

| 8.0 | 3.2 | 139392 | 128.0 | 160.0 |

The land use intensity rating applies to the total land area in a particular site. The rating scale appears in the first column of Table 1. For each rating, 0.0 through 8.0, a floor area ratio is given as well as the floor area per gross acre. Density in living units per gross acre for two different size dwelling units, 1,089 square feet and 871.2 square feet, is also given. It should be noted that for each full unit on the intensity scale the density, measured in living units per gross acre, is doubled. The 0.0 intensity rating at the 544.5 square feet of floor area per acre may be visualized as a single-family dwelling of modest size, 1,089 square feet of floor space, on a two-acre parcel. The same sized house with an intensity rating of 1.0, would be on a one-acre lot. The three dimensions given in Figure 3 — 871.2 square feet, 1,089 square feet, and 1,452 square feet — are not based on standard building sizes. Rather, they are respectively 1/50th, 1/40th, and 1/30th of an acre (43,500 sq. ft.). Because of this, they facilitate the preparation of the charts, and they are reasonably close to the floor area of a one-bedroom apartment, a two-bedroom house, and a three-bedroom house.

Once the rating is determined, Figures 1 and 3 are consulted to determine the permitted floor area and the number of dwelling units that can be built on the parcel. This is based on the floor area of the individual dwelling unit and the size of the tract of land. Thus, on an acre of land assigned a land use intensity rating of 5.0, a builder can place between 12 dwelling units of 1,452 square feet of floor area and 20 dwelling units of 871.2 square feet of floor area (see Figure 3). This is a gross density. The range of permitted net densities may also be found by computing the area devoted to streets. Figure 3 shows the range in net dwelling unit density with 20 to 25 per cent of the land developed to streets.

It should be noted that FHA no longer uses net density in reviewing projects. In the past this procedure often proved confusing, since at times public streets were counted and private streets were not, or a proportion of the area of abutting streets or open space might or might not be counted. The new FHA minimum property standards for multifamily dwellings now take gross land area as the base for land use intensity ratings. In making any comparisons with zoning ordinance densities, the reader should remember that most frequently zoning provisions are based on net land area — streets and alleys are not included.

FHA also uses "benchmarks" in determining the suitable intensity rating for a particular development. These benchmarks are actual projects that have been built and subsequently compared and analyzed in terms of the rating scale. Thus, the local insuring office will use examples of some actual apartment developments that have a certain rating. A proposed development can then be compared to see if the intensity and site planning standards are up to par with developments considered to be good ones.

Determining Suitable Intensity Rating. The step-by-step procedure to be followed by a local FHA office in determining a suitable intensity rating for a particular site will provide local officials with useful information for project evaluation. Surroundings of the proposed development, its relationship to the community, and the urban type of the community, are analyzed following the principles and using the measurement devices described in Land Planning Bulletin No. 7 (FHA) and in the revised provisions of Minimum Property Requirements for Three or More Living Units (FHA). The step-by-step procedure follows:

- To relate the site to the urban type: (Figure 9)

- Determine the urban type in which the site is located and find the group of range bars for that type at the bottom of Figure 3. Example: "Metropolitan Suburb."

- To relate the site to the space pattern of the community:

- Determine the sector of the community space pattern in which the site is located and find its range bar within the urban type found in Step 1 above. Example: "Center."

- Note the land-use intensity ratings for that range bar. Example: The 4.8 to 6.2 range.

- Consider that intensity range in relation to the intensity range appropriate for that particular community and that particular sector of that community. Narrow the range under consideration, or adjust it otherwise, as appropriate. Example: Recognizing weaker community and sector than the typical, the 4.8–6.2 range is narrowed to 4.8–5.8 for further consideration.

- To relate the site to common building types:

- Using the range of intensity ratings found in Step 2c, note at the top of Figure 3 under "Range of Optimum Use" the building range bars which are in that intensity range. Example: For the 4.8 to 5.8 range, they are a 2-story townhouse or apartment in the lower end of the intensity range, 3-story in the middle of the range and 6-story at the upper end.

- Consider this and if possible, narrow the intensity range to be considered further. Example: The 4.8 to 5.8 range is narrowed to a 4.8–5.6 range.

- To relate the site to density:

- Note the gross and net density for living units of typical sizes at the degrees of land-use intensity found in Step 3b above. Consider this and if possible narrow the intensity range to be considered further. Example: The 4.8 to 5.6 range is retained for consideration.

- To compare with typical "benchmarks":

- Note the characteristics of known projects charted as "benchmarks" in the Minimum Property Standards Manual or by local analysis, particularly those in the intensity range found in Step 4b above. Example: The 4.8 benchmark for the 2-story townhouse project in the is noted.

- Consider this and if possible, narrow the intensity range to be considered further. Example: An intensity slightly higher than the 4.8 benchmark design appears suitable to the site. The 4.8–5.6 range of Step 4b of the example is narrowed to the 4.8 to 5.2 range.

- To relate the site to the land-use standards: (Figure 1)

- Note the standards in Figure 1 for the intensity range found in Step 5b; note the doubling of floor area for each unit increase in Land Use Intensity Ratio (LIR) and the accompanying halving of livability space, and the reduction in car storage.

- Consider this, and if possible, narrow the intensity range for further consideration. Example: The 4.8 to 5.2 range of Step 5b is retained for further consideration.

- To relate to timing:

- Note the time stage of the development pattern of the particular community and the particular sector in which the site is located. Note the current market demand for additional housing supply at the intensities under consideration.

- Considering these factors, narrow the intensity range found in Step 6b or adjust it downward if indicated by the needs of timing and marketing for current use. Example: The 4.8 to 5.2 range of Step 6b is narrowed to a 4.9 to 5.1 range.

- To determine numerical land-use rating:

- Considering all the above, and working within the range of a land-use intensity found in 7b, determine that numerical degree of land-use intensity on the rating scale which is most appropriate for the subject site for FHA purposes; in other words, the intensity rating which represents the maximum intensity acceptable to FHA for the current use of the site for FHA-insured housing. Example: The 4.9–5.1 range of Step 7b is resolved at LIR 5:1.

Because local officials will still have to work within the framework of zoning ordinances to control land use and development standards, a translation of the land use intensity ratings is useful. A direct comparison with typical zoning provisions, however, can only be approximate, since the land use intensity ratings are based on floor area and zoning ordinance requirements on land area. Additional difficulty is encountered in translating densities. The FHA standards use a loose standard of gross measurement of dwelling units per acre whereas zoning ordinances use exact and net densities. However, if certain assumptions are made, it is possible to make rough conversions.

As most of the problems with apartments in the suburbs occur in metropolitan areas, the land use intensity ratings of 4, 5, and 6 are chosen for illustration. Two assumptions are made: Density is net density based on 20 per cent of the land area in streets with 871.2 square foot dwelling units; and the maximum floor area is used. Table 2 illustrates these kinds of conversions. Except for the parking requirement, all requirements are stated in relationship to land area.

Table 2. Typical Zoning Standards

| Land Use Intensity Rating | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| LIR 4 | LIR 5 | LIR 6 | |

| Dwelling units per acre | 12.5 | 25.0 | 50.0 |

| Lot area per dwelling unit (rounded) | 3,485 sq. ft. | 1,740 sq. ft. | 870 sq. ft. |

| Floor area ratio | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| Maximum coverage | 20% | 28% | 30% |

| Livability open space | 52% | 44% | 40% |

| Recreation space | 3.6% | 5.2% | 7.5% |

| Parking (inc. guest) | 1.6/d.u. | 1.2/d.u. | 0.95/d.u. |

The requirements in this table do not differ materially from some typical suburban zoning ordinance provisions. The three intensity ratings presented are similar to three separate residential zoning districts; low, medium, and high density. The high density example would be relatively rare in a suburban community, but the other two represent typical densities for garden apartments and two and three story walkup apartments now being built in many suburbs.

Of course, these intensity ratings are only three of the dozens that can be assigned by FHA to a particular project. In choosing a particular rating FHA has a large amount of flexibility in that there are as many ratings as lines on the graph. It is doubtful, and probably not desirable, that local agencies administering land use controls will ever have zoning tools as flexible as the land use intensity ratings. But the FHA approach is compatible with planned unit development provisions found in many zoning ordinances, and should prove useful in administering such provisions.

The pleas for more flexibility in zoning will undoubtedly increase as the new rating system becomes better known. However, no planning agency or local government should rush blindly into copying the FHA system. In the first place, it is too early to tell how well the system will work. Second, drafting a zoning ordinance with the FHA range of 50 or so separate density categories would be extremely difficult. Perhaps more needed in zoning is flexibility in varying structure types. The use of gross land area to compute density presents no difficulty, except in determining appropriate densities for vacant single lots in existing subdivisions. However, the use of floor area, rather than land area, as a base by FHA seems at times unnecessarily confusing. In addition, local officials need to know and to be able to control the number of dwelling units and the number of bedrooms for land use planning purposes. In fact, those zoning ordinances that use a density scale based on the number of bedrooms may be superior to the FHA approach. Most public officials will be more interested in how many school children will come from an apartment project, than in the sometimes over-subtle control of mass-structure-space relationships.

The FHA land use intensity ratings show the greatest promise in helping local officials review planned unit or large scale developments. While most existing zoning provisions of this type provide that the development must meet certain density limits, the ordinances are much too general and give too few standards to assist the reviewing agency in making intelligent decisions. It may be possible to prepare, as a part of the ordinance, a chart similar to Figure 1 to guide local agency review of planned developments. Instead of the "intensity" ratio, the base could be floor area ratio or dwelling units per acre, with the other standards related to the base. Depending on local conditions and desires, the graph curves could be skewed to require more or less open space, parking, or some other requirement.

Many of the factors in land intensity rating, such as parking, recreation space, and open space, are by no means new in zoning ordinances. It should be pointed out that planners have sought to include these kinds of provisions in zoning ordinances for a number of years. Usable open space requirements appear in some of the newer zoning ordinances, as do most of the other requirements. However, these concepts are appearing in FHA regulations for the first time, and, to the best knowledge of the authors of this report, no zoning ordinance contains standards for all of these items.

Zoning for Apartments

In drafting zoning controls for apartments, the first question that usually arises relates to density — how many dwelling units per acre should be permitted, or what should the minimum lot area per dwelling unit be? There is no universal answer to the question of an appropriate density for the suburban community. Densities adopted within the zoning ordinance will depend upon the suburb's comprehensive plan, density of existing development, availability and quality of various public services, typical development patterns for apartments within the larger metropolitan area, community attitudes, and a host of other factors. However, there are some broad general standards and guidelines that should be considered by local officials.

In addition to the new FHA standards, the American Public Health Association's Planning the Neighborhood (APHA) recommends density standards for residential development. Tables 3 and 4 summarize some of these numerical standards. Since the standards were originally developed in 1948, today they are considered by many planners as minimum standards. For example, the space standards for automobiles are out-of-date. However, because the standards are simple, in comparison with the FHA intensity rating, the publication is still an excellent reference.

Table 3. Net Dwelling Densities and Building Coverage

| Net Dwelling Density (Units per Acre of Net Residential Land) | Net Building Coverage (Per Cent of Net Residential Land Built Over) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Family | Standard: Desirable | Standard: Maximum | Standard: Maximum |

| 2-story | 25 | 30 | 30 |

| 3-story | 40 | 45 | 30 |

| 6-story | 65 | 75 | 25 |

| 9-story | 75 | 85 | 20 |

| 13-story | 85 | 95 | 17 |

Source: Planning the Neighborhood, American Public Health Association, Committee on the Hygiene of Housing, 1960.

Table 4. Lot Area — Recommended Allowance per Family by Apartment Type and by Component Use

| Land Area: Square Feet per Family | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dwelling Type | Total | Covered by Buildings | Outdoor Living | Service, Walks and Setback | Off-Street Parking |

|

Multi-Family |

|||||

| 2-story | 1,465 | 435 | 415 | 455 | 160 |

| 3-story | 985 | 290 | 315 | 220 | 160 |

| 6-story | 570 | 145 | 215 | 50 | 160 |

| 9-story | 515 | 105 | 215 | 35 | 160 |

| 13-story | 450 | 75 | 215 | 35 | 125 |

Source: Planning the Neighborhood, American Public Health Association, Committee on the Hygiene of Housing, 1960.

Both tables show that although recommended densities increase with building height, the recommended building coverage decreases. The need for outdoor living area is also taken into account by the APHA standards. The relationship, therefore, between density, height, coverage, and amount of outdoor space has been considered. This is not the case if standards are expressed only as a maximum density figure. Zoning ordinance provisions should incorporate control techniques that recognize these relationships.

As stated previously, this report will not attempt to set any specific density or space standards. Careful study of a few standard planning sources, particularly Planning the Neighborhood and the new FHA land development standards, along with selected zoning ordinances from neighboring cities, is about all local officials can do in looking outside their community for development standards. The local planning agency will find that most existing standards are based on traditional principles, current practices, and a mixture of hunch and compromise. The following section, however, outlines some of the basic elements that should be included in zoning ordinance provisions to control apartment development.

The first step is to determine the appropriate maximum permitted density. Although the new FHA standards have abandoned density requirements based on land area, municipalities are advised not to follow suit. In using requirements based only on floor area, the FHA standards are still experimental, and when used alone, do not take into account the number of families, children, bedrooms, or amount of traffic generation. Furthermore, some communities have found that the use of floor area ratio only as a density control in the zoning ordinance has resulted in developers building low structures covering nearly all the lot with little, if any, open space surrounding the building.

If densities are to be clearly stated, it is desirable to have a floor area ratio requirement to control building mass and its relationship to land area. In other words, FAR should be used as a bulk control to ensure a reasonable amount of open space, and not as a population control technique specifying the number of families per acre. Floor area ratio is also useful in conjunction with a bonus system whereby additional floor area is permitted if a building is constructed with additional stories but covering less lot space.

In addition to maximum density, most easily stated as a minimum lot area per dwelling unit requirement, there should also be a minimum lot size requirement. It is difficult to state categorically what such a requirement ought to be — local development standards will usually govern this kind of determination. But in general, a lot in a built-up portion of a suburb should be large enough to provide adequate off-street parking, yards, and open spaces. These generalizations apply especially to the occasional bypassed lots in older suburbs. The minimum lot size requirement is particularly important to guide development in areas zoned for multifamily development that contain a few vacant lots smaller than even the typical single-family lot. Where one- or two-family structures are permitted in multifamily areas, the apartment district regulations should require the minimum lot area for these dwellings be the same as if they were built in the one- or two-family zoning district.

A simple method of handling the small lot problem is by using a sliding scale. For example, suppose the community wished to establish a multifamily district at a density of 1,000 square feet per dwelling unit, in an area originally subdivided into 5,000-square-foot lots for single-family development. A five-unit apartment on a 5,000-square-foot lot is obviously overcrowding the load.

Therefore, as a part of the zoning provision for this district, the following tabulation is included:

Maximum number of dwelling units permitted in this district

| Lot Area in Square Feet | Dwelling Units |

|---|---|

| Less than 5,000 | 1 |

| 5,000 to 7,499 | 2 |

| 7,500 to 8,999 | 3 |

| 9,000 to 10,000 | 4 |

For each 1,000 square feet over 10,000, one additional dwelling unit may be constructed.

Maximum building coverage and height provisions are also typically included in zoning provisions for apartments. Of the two, coverage is perhaps the most important in terms of controlling the quality of the environment — particularly if the zoning ordinance does not contain usable open space provisions. Maximum coverage percentages suggested in Tables 3 and 4 should not be exceeded. Coverages may be computed from the FHA standards by taking the open space ratios and working back to arrive at building coverages, but the peculiar exceptions and allowances under FHA definitions must be taken into consideration.

In setting height limitations, suburban public officials must first decide whether residential buildings of more than three stories will be permitted at all. If not, the matter of drafting height controls will pose no serious problems. If the community does decide to permit buildings of more than three stories, the zoning ordinance should contain other controls, such as floor area ratio or angle of light obstruction provisions.8