Vest Pocket Parks

PAS Report 229

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 229 | December 1967 |

Vest Pocket Parks

Download original report (pdf)

In recent years, considerable interest has been stimulated by the experiment, in some of the larger American cities, with vest pocket parks. Although limited both in scope and size, these parks represent a serious effort to improve the quality of the environment in the more crowded urban areas.

Vest pocket parks can have broad application. Their impact, however, is likely to be greatest in those low-income, densely populated neighborhoods where outdoor public space is severely limited. In these neighborhoods, the development of parks which meet traditional size standards is difficult to realize. A system of vest pocket parks, on the other hand, may substantially improve recreational facilities for children and may provide needed services for other groups including older people. These parks may also improve the physical appearance of the neighborhood and contribute to upgrading the environment.

Since vest pocket parks are as yet at the experiment level, it is difficult to evaluate their effectiveness. The reaction, where they have been tried, ranges from quite favorable to very skeptical. In all cases, however, the concept at least is considered sound. While vest pocket parks are not a cureall for the problems of disadvantaged neighborhoods, the potential advantages are clear. Where the need for outdoor space is greatest, small vacant lots and land occupied by derelict buildings can be acquired, usually at low cost, to be developed into small parks. The actual development of facilities may involve the cooperation of the residents. This offers the opportunity to keep costs at a minimum and, equally important, encourages resident participation in meaningful projects from which they can derive direct benefit. As a result of this involvement, the residents may be stimulated to undertake additional neighborhood improvements. Finally, the vest pocket park can be an important physical improvement for the neighborhood and a step toward additional beautification projects.

In this report the potential of vest pocket parks will be explored in the light of the experiences in four major cities: New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington. The report will discuss specific programs and their financing, staffing, and implementation, but it should be understood that the report is not based on firsthand knowledge, but on information, and in part opinions, relayed to ASPO by the sponsors and participants in these projects.

HISTORY

Originally conceived in Europe after the second World War, the idea of vest pocket parks was brought to the United States in the early 1950's. In Europe the aftermath of the war left many of the major cities with a serious shortage of capital, labor, and materials to carry out needed reconstruction. Because of these shortages, shortcuts had to be found to restore the cities to normal peace-time life. In the area of outdoor recreation, these same limitations promoted the use of sites, laid waste by earlier bombing, for park space. This involved a minimum of expense, but a great deal of imagination. These small parks met with greater success than had been anticipated, and the concept was retained and applied on a broader scale in later years. Another outcome of these experiments was the adventure playground, which will be discussed briefly below.

In the United States Professor Karl Linn was instrumental in adapting the small park concept derived from the European experience to American cities. His approach was to persuade city officials in the cities of Baltimore, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia to create "neighborhood commons" by utilizing tax delinquent land.

This idea was favorably received for at least two reasons. The first was that, although the need to improve existing recreational facilities in densely populated areas was widely recognized, the cost to develop parks meeting the traditional standards was not always within the reach of the resources allocated for recreation.

Vest pocket parks, on the other hand, can be developed at a relatively small cost — estimated to be approximately $3.50 per square foot including land. If the land is already owned by the city, costs can be reduced even further. The reason for these more realistic costs is that individual lots are not highly desirable for commercial purposes.

Cost alone, although significant, is not the only consideration. The conviction that parks must be large is being questioned. In the urban setting the number of open spaces takes precedence over size. Much of the usefulness of park facilities can be measured in terms of accessibility. Small parks scattered throughout a neighborhood are more accessible than larger but more widely spaced facilities. Even if more effective in the range of purposes, the larger parks become separated from the users by distance compounded by traffic. Moreover, the residents of a neighborhood, especially children, develop a sense of identity and attachment to the immediate area. The surroundings are familiar, and personal associations are strong. Therefore, the smaller park is better suited to the needs of the residents.

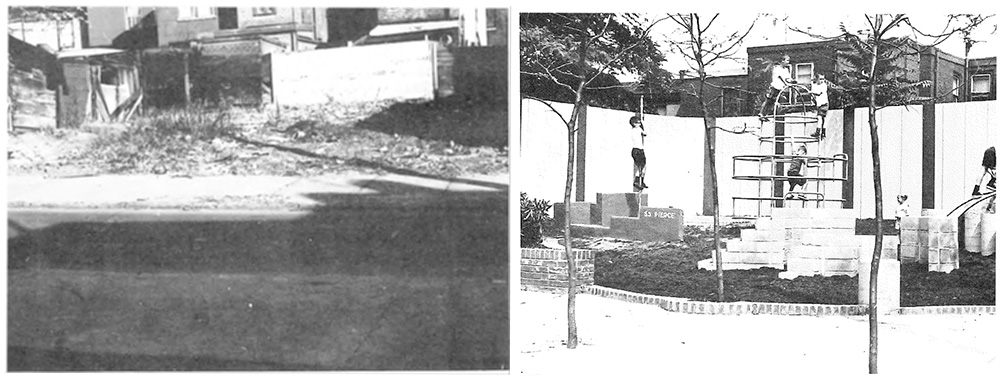

An attractive play area for children was carved out of a small and otherwise useless vacant lot in Philadelphia.

STANDARDS

Traditionally, outdoor recreation facilities have been defined clearly and precisely. As early as 1914, Charles Dowing Lay, a landscape architect for the New York State Department of Parks, suggested an ideal system of parks for a hypothetical city of 100,000 people. This system consisted of a series of parks, each with a different function and each of different size.1 In later years, through the efforts of such organizations as the National Recreation Association, standards for size, location in relation to the area served, specialized activities suited for each individual park, and appropriate equipment required were further refined and became generally accepted.2

Vest pocket parks do not lend themselves to such precise definition. As the accompanying photographs of vest pocket parks developed in Philadelphia illustrate, the basic characteristics of these parks is that they are small, substantially smaller than the one- to three-acre minimum usually prescribed for the smaller unit in the park system — the neighborhood playground or play lot. The actual size of the vest pocket park is determined by availability of land rather than pre-established standards, no matter how well thought out these standards might be.

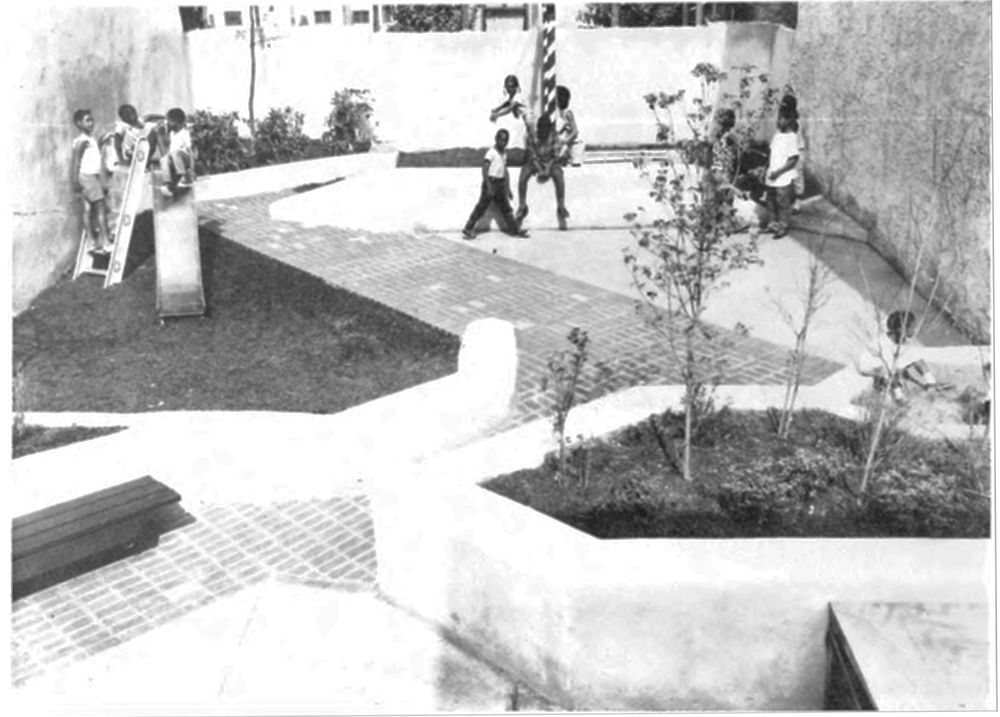

This photograph shows imaginative use of cement and bricks in another of Philadelphia's vest pocket parks.

VEST POCKET PROGRAMS IN FOUR CITIES

A number of vest pocket parks have been planned and developed in various cities. In 1965, New York City had 18 of these parks and was planning a network totaling 200 small neighborhood recreation areas. In Baltimore, the urban renewal agency is now adding 29 "inner block" parks, in two project areas, to the existing vest pocket parks operated by the city's Department of Recreation and Parks. Of the 29, 19 have been completed and 10 are under construction. In Philadelphia, where the vest pocket park program has been progressing at an accelerated pace in the last few years, 60 sites are now in operation, 60 more are under construction, and an additional 30 are at various stages of planning and development. The city of Washington has a vest pocket program underway; the experiment there, however, has not been as productive as in the other cities.

The Philadelphia Partnership

In Philadelphia the emphasis of the program is on the full utilization of neighborhood resources. At the same time the city plays a major role in promoting the development of parks by providing the necessary land, staff, and funds.

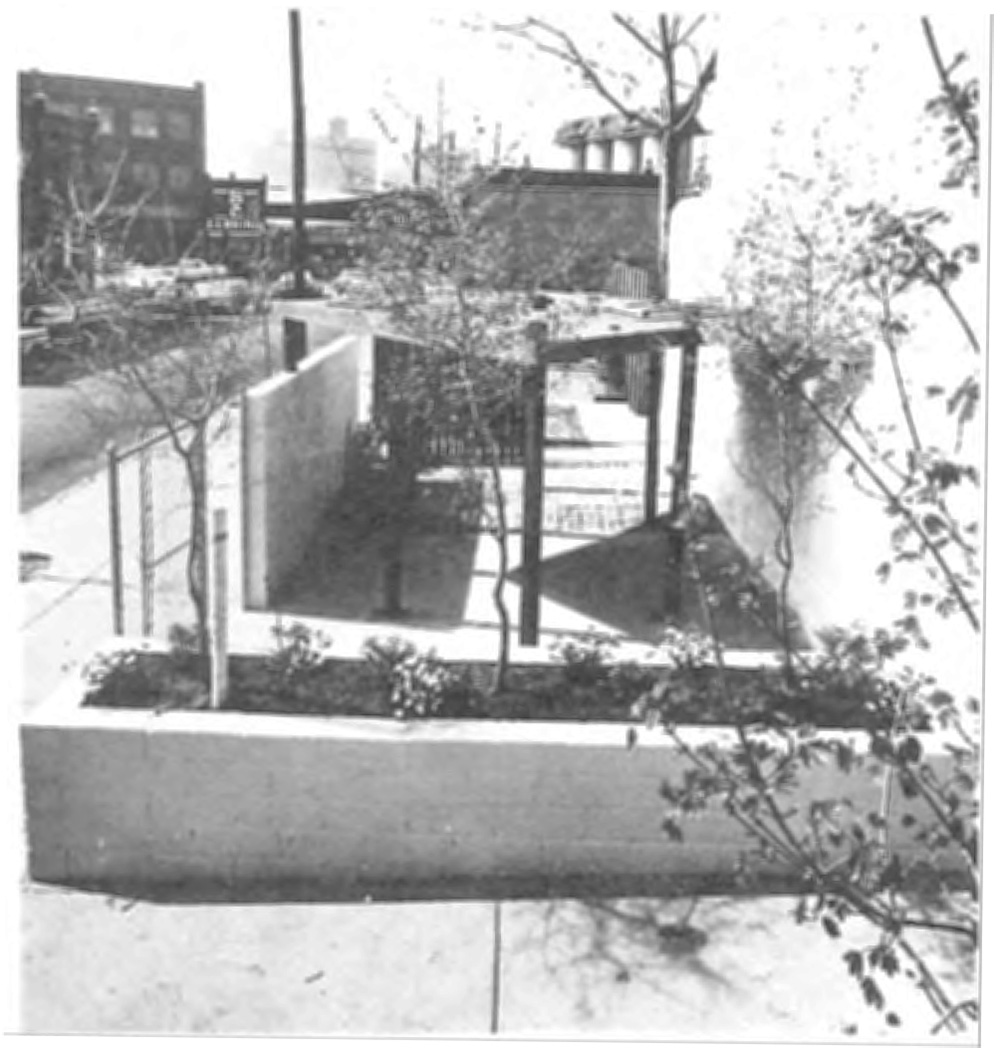

Space limitations precluded the use of play equipment in this example of a vest pocket park. A shaded area and a small flower bed are used to enhance the appearance of the surrounding area.

Space limitations precluded the use of play equipment in this example of a vest pocket park. A shaded area and a small flower bed are used to enhance the appearance of the surrounding area.

Although much is asked of the neighborhood group, financial support and technical know-how is made available by the city. The vest pocket park program has a budget, a staff, and the cooperation of various public and private agencies. This program, now relatively well staffed and financed, had rather humble beginnings. It started in 1965 with a $25,000 grant from a private foundation. Initial results were so encouraging that the city matched the grant to continue the program. Later, a federal urban beautification grant was added to the budget. By 1967, the annual budget for the vest pocket program had expanded to $323,000. Of this total, more than half ($183,000) is allocated by the city, and the rest ($140,000) comes from the federal grant.

The funds are used to prepare the grounds and to purchase equipment and material necessary in the development of the park. The money has also been used to assemble a competent staff which includes an architect, various skilled laborers, and a neighborhood educator. In addition to its own resources and those of the Department of Licenses and Inspections, of which it is a part, the vest pocket park program can depend on support from other sources such as the Department of Water and Streets, and the recreation and planning departments. Additional assistance has been provided by such private groups as the Junior Chamber of Commerce, various clubs and settlement houses, and by volunteer professionals.

The process begins with a request, by an organized group of residents, for a site to be converted into a vest pocket park. Once the project is approved, by the Department of Licenses and Inspections, the sponsoring group shares with the city full responsibility for planning, construction, and maintenance of the site. A fact sheet reproduced in Appendix A contains the basic information necessary to begin a vest pocket park project.

Land for vest pocket parks is available, at no cost, from the Department of Licenses and Inspections. This city agency, which is also responsible for code enforcement and neighborhood renewal projects, has been acquiring vacant land and structures under the "land bank project." Neighborhood groups interested in sponsoring a vest pocket park can obtain the necessary land from this source. If the neighborhood group does not have a specific site in mind, the city will provide information on available lots or on land to be acquired in the area at a future date. When no suitable land is already available in a specific neighborhood, the Department of Licenses and Inspections is authorized to acquire and demolish dilapidated, tax-delinquent structures for this purpose.

The responsibility of the neighborhood group is to select a site for development consistent with its needs. In general, facilities are to be developed for children and for adult leisure activities. The neighborhood organization is also required to maintain the property in good condition and to have insurance coverage for its own as well as the city's protection. Insurance coverage in the sums of $100,000–300,000 for public liability and $5,000 property damage (usually available at low cost) must be in effect when work begins. Specific insurance requirements and the license agreement for the use of city land by private organizations are reproduced in Appendix B.

The actual development of vest pocket parks is accomplished through a partnership between the land utilization section and local residents. The parks are designed by the staff architect who is assisted by volunteer professionals. The architect meets repeatedly with the residents of each neighborhood during the preparation of the layout. The discussions, guided by a community worker, ensures that the proposed project meets the needs of the sponsoring group and that the actual design is clearly understood by the residents so that they may fully participate in its implementation. Actual construction is then carried out by a crew of skilled laborers on the city staff with the help of residents who perform such functions as painting, bricklaying, and carpentry.

The average size of a vest pocket park is approximately the equivalent of three lots. Maximum size suggested is no more than four vacant lots. This size limitation is considered desirable since larger parks are more difficult to maintain. In a few exceptional cases, parks have been built on as many as 10 lots, but these are essentially two parks located back to back facing two parallel streets. They serve as a link between the two streets and have greater exposure than those surrounded on three sides by structures. This arrangement contributes, in good measure, to the improved appearance of the neighborhood and fulfills both a recreational and an aesthetic function.

Inventive use of limited space and resources is one of the major aspects of the vest pocket program. Sturdy and colorful equipment is both improvised and purchased from commercial sources. It usually consists of building materials such as bricks, concrete mounds, and tunnels. Poured concrete is used for table pedestals, jumping islands, and so forth. This equipment, along with trees and shrubberies, largely makes up the interior development of these parks. Fences are generally discouraged but, when considered absolutely necessary, colorful wood or painted chain link fences interspersed with redwood are preferred.

The vest pocket park program in Philadelphia has had both a physical and social impact. The parks have improved the environment by upgrading the appearances of blighted areas and by creating an outlet for much needed outdoor recreation space. More important, the rate of development has been such that the vest pocket program promises to make a real rather than a token contribution to the establishment of needed outdoor recreation facilities,

The involvement of residents, also an important part of the program, has promoted a sense of pride in the community and helped develop the skills and motivation necessary to undertake additional projects designed to further upgrade the neighborhood. In many cases these same resident groups, formed in conjunction with the park projects have proceeded with other community improvements after completion of the site. As a result, housing rehabilitation projects involving the housing authority and the Development Corporation of Philadelphia, in cooperation with the neighborhood groups, are now underway.

Inner-Block Parks for Two Baltimore Urban Renewal Areas

In Baltimore, the concept of vest pocket parks has been successfully applied in two urban renewal project areas undergoing an intensive program of rehabilitation. The small park concept is neither new in this city nor limited to these two areas. In the urban renewal areas, however, an intensive effort has been made to saturate entire neighborhoods with a complete system of parks and playgrounds with the ultimate objective of providing one park in each block.3 The program is designed to develop outdoor recreation facilities in the interior of each block. These parks, known as "inner block parks," will serve the residents of the Harlem Park area, predominantly lower-income Negroes, and the residents of Mount Royal, whose racial and income composition is more varied. In the first area 19 parks have already been built; in the second 10 are under construction.

Land for the inner block parks is obtained by acquiring and clearing, as part of the urban renewal project, dilapidated structures located in the interior of the block. These structures consist of small low-quality homes originally built as accessory residences for the larger and more luxurious row houses facing the street and which are often deteriorated beyond rehabilitation. Additional land is obtained by closing the alleys, which have lost much of their usefulness.

Once the land has been cleared, the actual process of development begins. As in other cities, the residents' participation in the project plays an important role. The formation of citizen block associations is encouraged by the urban renewal agency through community organization workers who are members of the agency's staff. Each block association meets with the landscape architects and staff planners to discuss the possibility of park development and later to review the plans. Final planning and contracting of actual development is carried out only after agreement is reached between the agency and the residents.

Originally, the urban renewal agency had attempted to give the block association major maintenance responsibilities. This attempt, however, was abandoned since the legal problem of liability and insurance could not be worked out. As a result, the responsibility of the block associations is limited to simple maintenance and house cleaning functions. Responsibilities for major maintenance and liability of the properties are retained, at least for the time being, by the urban renewal agency.

The effectiveness of the block association in maintaining and supervising these small parks has been found to vary considerably. In the Baltimore experience, difficulties were experienced in enlisting the cooperation of absentee landowners. Thus the effectiveness of block associations varied in direct proportion to the ratio of homeownership in the area.

The type of facilities installed reflects the range of tastes and desires of the residents expressed through the block association. The equipment for inner block parks varies. In general, however, the parks are designed to provide active play areas for pre-school children and passive areas for adults. Game areas, barbecue pits, and space for flower gardens are frequently found in these parks. Several of them also have simple shelters, and in one case a paved court used for both basketball and tennis is provided.

Surfacing materials for these parks vary in each block, but an effort has been made to use grass in preference to cement or asphalt surfaces. Experiments with loose surfacing materials such as tanbark (small pieces of tree bark especially treated for playground use) and gravel have not proved successful because of heavy use of the parks.

In equipping the inner block parks, the agency has avoided the use of active play equipment for older children since these parks are intended primarily for pre-school children and adults. Additional facilities for active play, to supplement the inner block parks, are provided in a larger area developed in conjunction with a new school.

The total cost for the development of 29 inner block parks in Baltimore amounts to $3,242,000. Of this, slightly more than half or $1,730,000 was spent for construction, landscaping, and equipment. The remaining $1,512,000 was spent for the acquisition of land. Since the park program is part of urban renewal, the federal government pays three-quarters of costs. Ownership of the parks is retained by the city.

Although it is too early to assess the success of these small parks, the Baltimore urban renewal agency feels that the basic purpose of reducing overcrowding of land, eliminating unsafe and unsanitary collections of junk and garbage, and adding necessary space for play and passive recreation has been accomplished. Another major accomplishment is the establishment of neighborhood spirit and pride often lost to an unpleasant and hostile environment.

The major difficulty incurred with inner block parks is the damage resulting from over-use inevitable in high density areas where the ratio of residence to open space is low. Damage is even more pronounced where the park developed in one block is shared with the residents of surrounding neighborhoods who lack similar facilities. Additional parks should, however, alleviate this condition. Better utilization of facilities is possible when leadership for supervision of activities is available. The experience in Baltimore with Operation Camp of the anti-poverty program and with VISTA volunteers showed that more meaningful use of parks can be realized through supervision and organization.

New York

The New York program started in the early 1930's when the city's Bureau of Real Estate acquired small lots through tax foreclosures. Some of this land, along with the resources of the recreation department which developed the sites and installed necessary equipment, was made available to private organizations to be used for recreation purposes.

In later years the efforts to provide small parks through this method have been intensified. The same approach is followed now, although the major responsibility for the vest pocket program has been shifted to the Department of Small Parks. Since private agencies have also taken an active part in the development of vest pocket parks, coordinating private and public efforts is an added but important responsibility of this department.

Facilities are developed through the transfer of city-owned land to the department which also assumes the responsibility for construction and maintenance. Efforts are now made to consult with the residents of each neighborhood for suggestions on design and equipment. In several instances, residents also volunteer their help for actual construction. Although citizen participation is continuously encouraged at all levels, the major responsibilities for the vest pocket program rest with the Department of Small Parks. Of the city-owned properties, seven are leased to HARYOU-ACT Incorporated, five to the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Councils, and one to the East Harlem Tenants Council, at $1 per month. In addition to the city-owned facilities, small parks have been developed on properties acquired for this purpose by private organizations. The Park Association of New York City, for example, has financed experimental programs in design and operation with three vest pocket parks which are used by various church organizations.4

Washington, D.C.

In Washington, D.C., the small parks program was initiated by the Neighborhood Commons, a private, nonprofit corporation which received preliminary impetus and guidance from the Washington Center for Metropolitan Studies. With the city's encouragement, the corporation has prepared a list of public and private sites which, for a nominal fee, can be made available to groups interested in sponsoring small neighborhood parks. Every project must be endorsed by an established local agency such as a block association, a church, or a neighborhood group. The Neighborhood Commons enters into contract with the local agencies and provides volunteer designers, field supervisors, and staff members to oversee development of individual sites. This organization also helps obtain construction materials and equipment from outside sources to supplement the resources available in the community.5

The local sponsoring agency is responsible for the execution and supervision of plans and designs endorsed by the Neighborhood Commons. It also organizes volunteers, drawn from local residents, who donate time to actual construction. Finally, it assumes full responsibility for the maintenance of each park including insurance coverage.

PLAY EQUIPMENT AND ADVENTURE PLAYGROUNDS

Selection of vest pocket park equipment must be guided by the recognition that these facilities have limitations and that they are intended to meet certain specific needs of the neighborhood. Because they are small and because they can be closely spaced, these parks are best suited for use by the least mobile members of the community. This includes pre-school children who, for reason of safety, should not be required to travel great distances to reach play areas and for the elderly residents. Equipment, therefore, is selected to meet the needs of these two groups and to discourage use by older children who require, for their more energetic play, larger areas than can be provided in these small parks. Play areas for teenagers are usually developed in conjunction with school facilities.

Since in most cases the residents play an active role in planning, construction, and maintenance of vest pocket parks, a degree of flexibility is desirable to allow this same participation in the selection and, when possible, in the construction of suitable equipment. In general, small parks seem to function best with as little equipment as possible. Play structures occupy valuable space which, in vest pocket parks, is limited. In addition, elaborate equipment lends itself to vandalism — a pressing problem experienced in vest pocket parks.

Equipment for a vest pocket park is frequently similar to that found in the more traditional playgrounds. It has been observed, however, that children often make up games which do not necessarily follow the restrictions imposed by the facilities provided. Frequently, the equipment is made to fit a pattern of play for which it was not intended. Damages, often attributed to vandalism, are in many cases the direct result of misuse.

The concept of the "adventure playground" has been suggested as an alternative approach, more realistically suited to the needs of children. The adventure playground emerged in Europe during the German occupation of Denmark. The idea is attributed to Professor T. Sorenson, architect and designer of many large parks in that country. In watching children play, he noticed that they preferred rubble-filled lots and construction sites to the more elaborate parks even when these were available and easily accessible. He reasoned that the opportunity to experiment with various materials, to build and demolish according to the whim of the game, all in a permissive atmosphere, was a preferable outlet for their energies and their imagination than the more elaborate but more restrictive environment of the parks.6

The concept of the adventure playground was derived from this observation and, in later years, was applied in various countries including Switzerland, Sweden, and England. In the United States "The Yard" in Minneapolis is an adaptation of this same concept. Similar experiments have been tried in other cities with varying degrees of success.

In its practical application, the incorporation of the adventure playground into a vest pocket program raises the question of safety. The equipment for these playgrounds is readily available and inexpensive since it consists mostly of discarded materials, but it is not necessarily safe. Children play should therefore be supervised by qualified adults. In the vest pocket parks, and consistent with the concept of minimum expenditure and maximum involvement of residents, volunteers can be used for this purpose. Parents and elderly citizens willing to donate their time can be organized to provide the leadership and supervision required. In addition, supervision may be available from such programs as VISTA and other poverty programs.

FEDERAL AIDS

It is evident that the vest pocket park program requires funds. Although the use of small parcels of land and the involvement of volunteer services can realize substantial savings, substantial sums are necessary to establish a comprehensive program. Experience indicates that these parks can only be effective when they are closely spaced and accessible to the residents. The resources available from the city's own budget can be implemented with federal funds available for this purpose.

The Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965 provides grants for open space land programs and for urban beautification and improvement which can be applied to vest pocket parks. These grants can be used for the acquisition and development of land and for recreation equipment. In all cases the moneys granted cover up to 50 per cent of project costs. Funds are also available for the establishment of local programs designed for greater use and enjoyment of open space in urban areas.

CONCLUSION

Vest pocket parks have been suggested as an. effective means to improve the urban environment, especially in the more densely populated neighborhoods. Although the experiment is too recent to allow for firm conclusions, two requirements stand out. First, active participation of the residents is essential both to overcome limitations of resources and to ensure that the people to be served by these facilities assume a vital role rather than being the passive recipients of another social program.

Second, vest pocket parks can only make a substantial contribution if they are closely spaced, preferably with one facility in each block. Neither of these objectives is easily obtained. Hopefully, experiences reported here will serve as guides in the development of similar programs in other areas.

ENDNOTES

1. American Society of Planning Officials. Standards for Outdoor Recreational Areas. Planning Advisory Service Information Report No. 194. Chicago, Illinois. 1965. 44 pp.

2. For an extensive discussion of those standards see ibid.

3. Steiner, Richard L. "Vest Pocket Parks — Baltimore's Experience in the Harlem Park Urban Renewal Project." In Planning 1967. Chicago: American Society of Planning Officials. 1967. P. 235.

4. New York Department of City Planning. Report of the Temporary InterAgency Committee on Vest Pocket Parks. December 20, 1965.

5. Stockard, James G. Designing Neighborhood Commons. The Washington Center for Metropolitan Studies. 1964.

6. Lady Allen of Hurtwood. New Playgrounds. The Housing Centre Trust, 13 Suffolk Street, London S.W. 1, 1964.

APPENDIX A

CITY OF PHILADELPHIA DEPARTMENT OF LICENSES AND INSPECTIONS

Gordon Cavanaugh, Commissioner

NEIGHBORHOOD PARK PROGRAM

A vacant lot can be:

an eyesore

a danger to health and safety

an automobile graveyard

an invitation to crime — or

It can be:

a tot lot for small children

a play space for older children

a restful sitting area for senior citizens

a flower garden

You and your neighbors can make the difference:

Under the Land Utilization Program of the Department of Licenses and Inspections, vacant lots can be assigned without charge to community groups or individuals for any outdoor purpose which will improve the neighborhood and benefit its people.

Residents will:

help decide on the type of park

cooperate in building it

keep the park clean and attractive

The land utilization section will supply:

a professional architect

construction equipment and tools

skilled workmen and advisors to work with residents

new sidewalks and other paving

some materials and equipment

trees and shrubs

Most City-owned vacant lots are available for use. The Land Utilization Section can acquire others and occasionally demolish a vacant and dangerous building if a group wishes to improve and maintain the site.

Call or write the Land Utilization Office if your group would like to visit some of the completed parks or if you would like us to meet with your organization. We can be reached at:

Land Utilization Section

Room 710 Municipal Services Building

15th and Kennedy Boulevard

Municipal 6-2506

APPENDIX B

CITY OF PHILADELPHIA DEPARTMENT OF LICENSES AND INSPECTIONS

LAND UTILIZATION PROGRAM

INSURANCE PROCEDURE

I. Contact any insurance company or agent of your choice.

II. Explain to your agent that you require the following coverage of the Owners, Landlords and Tenants type:

(a) Public Liability — $100,000/$300,000

(b) Property Damage — $5,000

(c) Coverage is to take effect at the time the sponsoring group launches any work on the site, and must include construction activities.

IIL Request the agent to give you a "Certificate of Insurance" which contains the following:

(a) Addresses of all lots covered by the policy

(b) Endorsement naming the City of Philadelphia as one of the insured

(c) Statement that the City will receive ten days' notice prior to cancellation of the policy

(d) Coverage against any claims arising from construction activity.

IV. Forward the "Certificate of Insurance" to the Land Utilization Section, Department of Licenses and Inspections, Room 710, Municipal Services Building. Please retain the original insurance policy.

V. The above requirements must be fully complied with before the license agreement can go into effect. If you require additional assistance, please call Municipal 6-2506.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Coffey, Michael, and Harris, Harry G. "A Report and Recommendations on the Community Use of Vacant Lots Submitted to the Ford Foundation," 1964. Unpublished.

Goodman, Charles, and Von Eckardt, Wolfe. Life for Dead Spaces: The Development of the Lavanburg Commons. New York Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1963.

Rowing, Thomas P.F. "Think Big About Small Parks," New York Times Magazine Section (April 10, 1966).

Linn, Karl. "Melon Neighborhood Park," Landscape Architecture, (January 1962), pp. 76–78.

Little, Charles E. Stewardship. The Open Space Action Committee, 145 East 52nd Street, New York, N.Y. 10022.

Lowry, Joseph F. "Pilot Project Converts on Eyesore Park in N. Phila.," Philadelphia Evening Bulletin (February 27, 1962).

Neiring, William A. Nature in the Metropolis. The Tri-State Regional Plan Association, 230 West 41st Street, New York, N.Y. 10036.

Rosenblatt, Arthur. "Recreation: A Chance for Innovative Urban Design," Architectural Record (August 1967).

Siegel, Shirley Adelson. The Law of Open Space. The Tri-State Regional Plan Association.

Films

My Own Yard To Play In. Spontaneous play in slum streets and vacant lots. 16 mm, black and white, sound, 6 minutes. Produced by Phil Lerner. Distributed by Edward Harrison, New York City. 1959.

One in Ten Thousand. Volunteers develop a neighborhood playground on a bombed site in Stepney, London, under the sportsmanship of the Civic Trust. 16 mm, black and white, sound, 12 minutes. Produced by World Wide Pictures, Ltd., London. 1962.

Prepared by Piero Faraci. Copyright 1967 by American Society of Planning Officials.