The Open Space Net

PAS Report 230

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 230 | January 1968 |

The Open Space Net

Download original report (pdf)

Urban open space is under increasing pressure. Providing it, conserving it, and using it wisely mount in importance as development intensifies and spreads and land costs mount.

The open space net, built by joining major public, quasi-public, and private open spaces into a continuous system, promises increased economy and efficiency through combined use, and increased amenity in the form of greenbelt parkways. Most of the gains can be achieved without major increases in public expenditures.

To be effective, the net must become a central coordinating element in planning — not something happening occasionally and in patches by fortunate accidents, but a sustained and purposeful combination of multiple means to meet multiple ends. Both means and ends must be examined in the context of the net system. When this is done, the system has dramatic promise, but it becomes apparent that some traditional planning concepts may have to be altered and improved.

Preoccupation with extensive long-range patterns can lead to astigmatism on more intimate relationships in the family and its immediate environment. For a balanced view, what follows begins with consideration of the open space net in broad city and suburban context, discusses potential improvements which the net might bring to the family and neighborhood level, and concludes with some notes on implementation.

Open Space in the City — Changing Functions and Patterns

Since cities began, the importance of urban open space has been recognized. Form, function, and relationships have changed, but major open space was there. Sometimes it was public — the agora, the town square. Sometimes it was quasi-public — the temple or cathedral grounds, the campus. Sometimes it was private, surrounding the homes of the rich, the palaces of the mighty. Fortunately, it was usually distributed in such a way as to relieve the depressing density of urban development.

In time, many cities linked their major open spaces with boulevards or parkways, providing at least partial continuity and impressive vistas. Emperors and kings carried out grand designs with little concern for relocation of displaced persons, and Napoleon, in decreeing that old walls around inner cities should be replaced by parks, was uninhibited by concern over property rights or speculative values.

In the early 1900's, city planning in the U.S. moved toward classic revival:

Plans were of colossal scale, with monumental proportions. Axes shot off in all directions, terminating with proposed buildings that put the visions of past kinds to shame. Great plazas and broad avenues, generously punctuated with monuments, were almost a civic obsession. The "City Beautiful" was the Grand Plan reincarnate; the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris was the fountainhead for the designers of this period and the plans had to be big to be beautiful ...

All this activity was performed in something of a vacuum. An air of haughty detachment pervaded the planning, an isolation from the affairs of people and community activities. ... It was as though the planners had determined that the people must adjust themselves to the mighty formal arrangement. It failed to occur to them that the entire development of a city was essentially a derivative of human needs.l

Since then, cities have become more complex, public services have increased in scale and scope, and human needs have become a major consideration. The current move toward the open space net reflects this change.

Moves Toward the Net

In recent years, there is mounting interest in creating an open space system:

We are groping here for a framework within which many kinds and varieties of public and private uses, balanced out in detailed short-range plans, can shift and change and mix and separate through the centuries. And we should start with public land.

On this, we should move consistently toward an extensive and, where possible, continuous network of public land adapted to multiple purposes — open space, recreation, protection of watersheds and water supply, parks, schools, public and quasi-public buildings, transportation in whatever form it may take, and things as yet unknown.

The public land net is the permanent objective, the historic goal. It can be achieved by pursuit of a series of short-range ends (which in relation to it become means). As present and future short-range public requirements unfold in a series of plans adapted to their particular times, lands contributing to the net should be acquired and held. Basic policy should be to add to the net by every appropriate device.2

In the years ahead, continuing effort to relate public and quasi-public actions to building the public land net will multiply benefits (and particularly amenities), reduce costs, minimize the effects of errors in foresight, and provide for both present and future needs. ...

The land net becomes an organized public land reserve, built by combining uses involving substantial open space, growing gradually to completed form, and adapted to use and reuse in ways foreseeable and unforeseen as long as cities stand.

Within the net, islands for private uses are served, interconnected, shielded, and buffered by the threads which set them apart. The existence of the net as a preferred location for land-consuming public uses gives private areas within its meshes security against disruption by unpredictable public action. The net makes logical major land use divisions easier — within one reticulation may be a regional commercial center, within another, an industrial park.

Most spaces within the meshes may be used for balanced residential communities with supporting commercial and service facilities. Here the net provides access and a perimeter greenbelt, and the location of principal entries to the community from outside traffic arteries and transportation facilities sets the destination for internal collector streets and begins to establish a desirable internal pattern of land use.3

Emphasis above is on public and quasi-public uses inside the net. But there are obvious possibilities for inclusion of private uses involving substantial amounts of open space, if public controls can assure compatibility.

S. B. Zisman, long a proponent of more intelligent use of open space, observed in a paper in 1964:

Open space in the past was, largely, a negative concept — the areas for non-building. It is now coming to be recognized as a positive element for urban growth. In the decades ahead open space as a system can become the means of control in development. If it is to achieve this role, a new text of planning policies and programs must be written — and followed into practice. The issues are not for planners alone. They will be fought in the political arena, and out of a public consensus may come the new tools and new means, both public and private.4

There are now gropings toward more definitive statements of the problems and potentials. In a recent symposium, the American Public Works Association outlined needs for research on better utilization of public space, including "the outlining of public space network possibilities to increase the output of public space for community life."5 Related matters included criteria for uniform identification of public space, dimensioning present and future space functions, determination of principles on optimum spatial distribution of socio-economic activities, interrelationship of public and private properties, and so on.

A related approach is systems engineering for satisfaction of open space needs:

There is increasing demand for more extensive, and better quality, open space provision in all metropolitan areas. The provision of such space, and in particular its coordination with other facets of metropolitan development — transportation and land-use planning, water resources planning, residential and recreational development — may usefully be viewed as a problem in systems engineering.

In this case, the "system" is the totality of urban open space — parks, freeways, streets, building surroundings. The "objective" is to satisfy a hierarchy of differential demands — open space for recreation, for civic design, for pollution control or as a device to define the physical structure of the urban community and add a sense of scale and direction — and at the same time to coordinate and make better use of the many different types of space which exist in an urban area.6

In essence, the current idea is to create an open space system by combining public and quasi-public open space wherever reasonably possible, and adding to the spaciousness and efficient functioning of the net by encouraging appropriate and controlled integration of significant private open space. Experience with planned residential developments suggests strong advantage in combining common open space with adjacent net lands, and the possibilities do not stop here. High-rise apartments, town house clusters, and other forms might well fit.

The Undimensioned Need for Open Space

Long-range need for open space is unknown, and will remain so. Research to refine the net concept, to determine what would build the net, reinforce it, enlarge it, protect it, make it more efficient and research to determine potentials and timing for action will serve a useful purpose. Beyond this, a priori reasoning suggests putting the idea to work promptly.

As with a great deal of planning, exotic, complex, and futile research can be an expensive deterrent to needed action. The net concept is flexible, can accommodate to a wide range of errors in assumptions and forecasts, and can provide for a wide range of unknowns and unknowables. The nature of the problem assures that errors and uncertainties will be there, and on many of them elaborate research is unlikely to produce long-range answers of greater utility than those developed by simpler reasoning.

There will probably not be an oversupply of urban open space so long as we have cities. It is unnecessary to exploit all research potentials before proceeding to action which is obviously needed, and the sooner the better. For those still inclined toward elaborate detailing of long-range future requirements for urban open space (and other things) it may be well to underline the difficulties.

Areas of Uncertainty

Changes in Population. Thus far, we have been unable to forecast long-range changes in number or characteristics with any usable degree of precision. Check the record on items as "simple" as 20-year predictions.

Changes in Public Services. These have been rapid, and amount and scope will continue to increase, but only predictably within broad limits. What would be the effects of free and efficient mass transportation? Of economic "public service" in the form of a guaranteed minimum income?

Changes in Standards. Look at the record for the past 30–40 years on amounts and kinds of recreational space which should be minimum or standard. As a more striking example, take schools — their size and place in the neighborhood or community, their space requirements, increased proportion of population attending as education lengthens, attitude toward general community use of buildings and grounds, past effect of auto and bus on size of service area, potential effect of bussing as a device to assure socio-economic homogeneity, possibilities for major educational campuses concentrating far greater numbers of elementary students and perhaps combining school levels which are separate, and so on. Or review changes in standards for street widths, particularly arterials and the recently born system of freeways. What lies ahead will change rapidly. But how predictably?

Changes in Tastes, Customs, Tolerance. The generality of the "general public welfare" is increasingly broad (metropolitan, regional, and beyond) and increasingly deep (including future as well as present generations). Recent decades have seen vastly altered tastes and customs, changes in what people want to what they will put up with. Changes in the future will probably be more rapid.

Changes in Technology. The exponential curve of physical technology is taken for granted, but where it leads in terms of specific products, servicing, distribution, or processing is highly speculative. Social technology is also advancing, compounding problems of prognostication.

Thus long-range need for open space must remain in large measure undimensioned. The net concept is valid in spite of the uncertainties. In fact it gains attractiveness because of uncertainties. Open space isolated is more difficult to reuse effectively as open space than open space integrated into a system.

ELEMENTS IN THE OPEN SPACE NET

The net is intended to serve, to separate, and to buffer in areas where buffering is needed. Where it performs all these functions, its pattern is as follows:

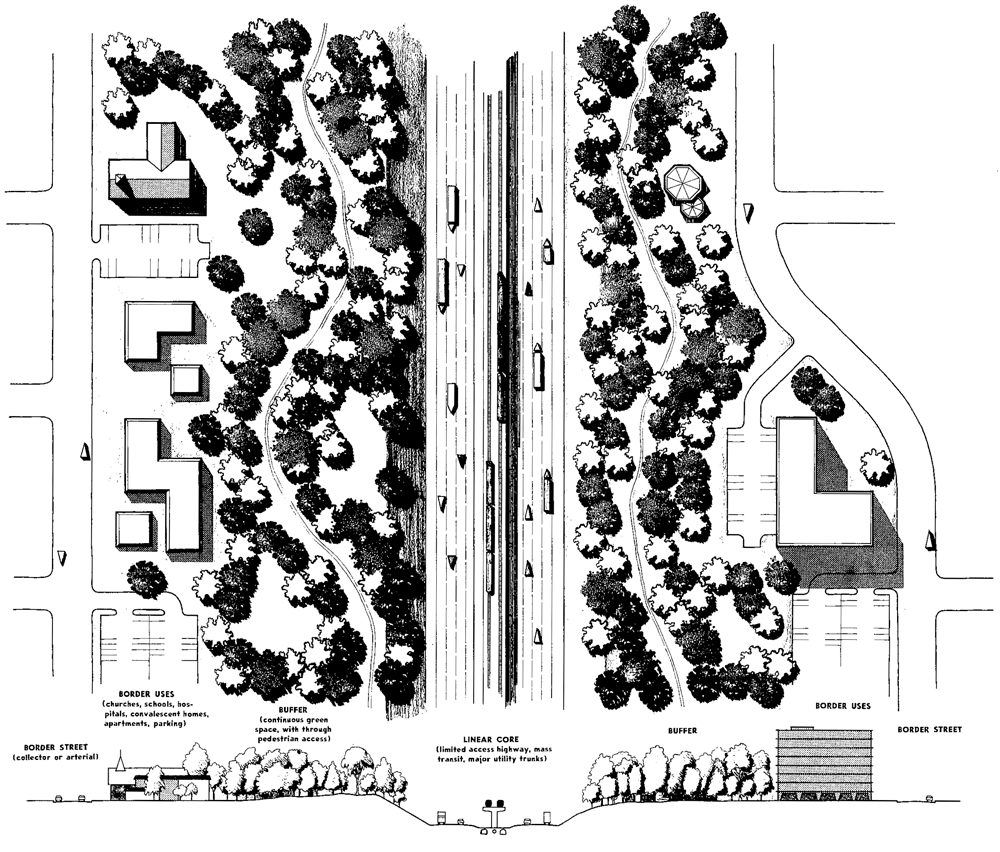

| Border Elements | Buffer Elements | Linear Core Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Collector or arterial street at outer edge of net forming boundary. Close to street, public, quasi-public, and private uses with substantial open space requirements, with space merged to contribute to buffer. | Parklike open space, preferably continuous with minimum of vehicular interruptions. May contain uses with only minor structures. Should contain pedestrian ways. | Limited access highways, mass transit, major utility trunks, and the like. |

All of these elements will not always be present. Thus through commercial or industrial areas, the linear core may suffice. And where parks or other open uses provide portions of the net, there may be no linear core.

These elements, illustrated in Figure 1, are discussed in more detail below.

Figure 1. Detail Plan and Cross Section of Net.

Linear Core Elements

One group of elements in the open space system is essentially linear, taking the form of interlocking corridors.

Limited access highways, chiefly freeways and expressways with interchanges and access points in urban areas generally at intervals of half a mile or more, are prime determinants. They now tend to serve primarily as automotive arteries, but could often handle additional functions. Certainly they separate, in many cases into divisions of workable size for primarily residential neighborhoods, and into other divisions adaptable for major shopping centers industrial parks, office complexes, civic centers, or institutional groupings. These arteries, as related to uses which now adjoin them, tend to create a need for buffering, rather than to provide it.

Mass transit rights of way should wherever practicable be combined with limited access automotive systems. There are obvious reasons of efficiency and economy. Given two systems, automotive and mass transit, taking large numbers of people from the same general origins to the same general destinations and back, the same routes should serve. If properly designed stations (and parking areas) are integrated into selected prime interchanges in outlying areas, the highway system serves as a convenient collection device for mass transit customers. Use of mass transit from such points through the most congested part of the highway system should increase, and use of private automobiles should lessen. And if the noise of mass transit is a problem to adjacent uses, the same buffering used to reduce highway noises can serve a double purpose.

Some major utility installations require substantial open space, or would benefit from improved accessibility for maintenance if located in the net. High tension transmission lines and major sanitary and storm sewer, water, and gas trunks are the principal examples.

Some parks are linear, particularly those along the bottoms of stream valleys. They separate and buffer, but often serve and often should serve only park purposes. There are times when multiple functions are desirable and times when they are not. Adoption of the open space net concept does not imply that existing or proposed parks should be targets for freeways, mass transit routes, or visible utility lines. There will be times when a park can be created in connection with development of such facilities, but there are few cases when such facilities should be allowed to invade or destroy existing parks.

Buffering and Bordering Elements

How and whether the linear core elements should be filled out with buffer and border depends on what lies within the meshes of the net. Where it embraces uses not likely to be adversely affected by the concentrated noise and lights of high-speed automotive or mass transport vehicles — heavy commercial areas, warehousing, and industrial uses, for example — there may be no need for greenbelting. But where traffic corridor elements of the net embrace areas of residential, institutional, or similar character it will be desirable to encourage buffering by promoting location of uses requiring substantial open space at the borders of the net and merging their open space into a buffering greenbelt.

Structures and parking areas for bordering uses should be concentrated next to the street at the outer boundary of the net, so that the related open space remains as continuous and unbroken as possible.

There is of course considerable latitude as to the amount of buffering desirable and the kinds of bordering uses which might be expected to require and provide it. Here the buffer might be wide, there narrow, depending on what is being shielded. This variation in circumstances broadens the range of uses which can profit from location in the net.

Public, quasi-public, and private buffer or border uses adaptable to the net include the following:

Parks, golf courses and other open recreational uses are obviously appropriate to the buffer and border strip. In such locations they are easily accessible from adjoining residential neighborhoods. They are particularly accessible from multi-family developments which may be located within the strip itself, and from schools which may be within the strip.

In some locations, open space reserves for specific or general future needs can be put to interim use in a way which conforms to buffer and border principles and also provides revenue. Thus lands in buffer locations might be acquired early for future school or park sites and leased as private golf courses, driving ranges, riding stables, camp grounds, and the like.

Schools, institutions, churches, and other public and quasi-public buildings and lands offer a broad gamut of possibilities, adaptable to buffering needs and the kind of bordering structures and uses appropriate to space of such dimensions. The branch library, the local health and social service clinic, the fire station, the police station don't need much room but fit well into the logical pattern of neighborhood uses at the border.

Churches, with a wide range of space needs, make good border uses, and their green spaces (including perhaps cemeteries) serve effectively to build buffer. As multi-service institutions, churches will usually welcome accessibility to the general green area for outdoor functions, and where churches are located close to higher-density residential uses in the buffer-border strip, the pedestrian circulation provided should be helpful in building attendance.

Institutions of various kinds benefit from border locations and from combinations of their grounds with the green buffer strip. Hospitals, sanitariums, convalescent homes, homes for the aged, children's homes, and the like would obviously fit well.

Schools should be both a major contributor and a major gainer. Elementary school structures in border portions of the net, with grounds made part of the buffer, are logical in the open space system context, but require revision of some traditional ideas about the place of this kind of school in the neighborhood.

Since elementary schools are major users of open space, and could be major contributors to the net, the argument for a shift from central location in the residential neighborhood needs special emphasis. Increasing proportions of children are transported to school by bus or automobile, and for those who walk or ride bicycles automotive traffic is a mounting hazard. Moving the school to a border location in the net gives rapid vehicular accessibility from the boundary arterial or collector street, and for children going to and from school on foot or bicycles, the buffer portion of the net provides safety for at least that part of the trip. Reorganization of daily trip patterns which follows as a result of adoption of the net concept results in a more convenient and efficient combination of travel to school, commercial facilities, work, and other destinations.

There is also the matter of flexibility in use and reuse of school grounds and possibilities for expansion. In long-range perspective, a great many schools built a generation or two ago are no longer in the best functional locations, or have grounds submarginal by present standards. If the old school is vacated, its land is often isolated in locations not well adapted for open-space reuse (or is "too valuable" for open-space reuse). Learning from this experience, there is no assurance that schools being built now will meet future standards either as to size of plants or amount of open space. The possibility of campus-type elementary facilities mentioned earlier is only one clue to this type of obsolescence.

Given border and buffer location in the net, there is first the possibility that provision for future expansion would be easier; second, the probability that availability of parkway open space would reduce acreage requirements for a particular school; and third, an improved probability that should the school be found to be at the wrong location in relation to future patterns of development, the land remains available in the net for other uses requiring substantial open space.

Junior and senior high schools, colleges, and universities are excellent net uses, with locations close to interchanges giving easy accessibility from a wide service area. As tract requirements increase, it may be difficult in some instances to place the whole establishment in the border and buffer area, but divisions of functions adapted to the net idea make adjustments possible. Thus the physical education plant with its fields and stadiums, open-air amphitheaters and the like might form border and buffer uses, with more densely occupied portions of the establishment outside the net across the perimeter accessway.

Areas where slopes, soils, flood hazards, or similar conditions impede development are very often suitable for inclusion within the net. Sometimes such areas will serve as buffers to a traffic-handling linear core. Elsewhere they may separate neighborhoods without containing major traffic-handling facilities. If they can be tied into the net, it may be easier to protect them (as parks, small "wilderness areas," or wildlife sanctuaries) than if they remain isolated, and certainly inclusion as part of the net should increase their accessibility. The physical characteristics which inhibit urban development often provide a rich variety of plant and animal life and a taste of wild solitude rare in the city environment.

Watershed protection areas, water storage areas, and even some forms of sewage treatment may be included. To some extent, these may overlap previously discussed categories — parks, wilderness areas, wildlife sanctuaries, etc. But there are some special possibilities which might be overlooked:

Where there is high run-off and low absorption (as may often be the case along major freeways with their extensive paving) water-storage ponds can be provided in the buffer strip to contain and control run-off.

Some forms of sewage treatment may be appropriate in certain buffer areas. A conventional treatment plant might fit at the ends of buffer strips where pedestrian circulation is interrupted by interchanges, and sewage lagoons would be appropriate there and in other locations.

The serial ponding type of treatment being pioneered at Santee Lakes in San Diego County, California, is a particularly good example of a type of multipurpose use adapted to inclusion in the net. Here a park area bordered on one side by a potential freeway right-of-way and on the other by a flood control channel is developed around five ponds. The first is an oxidation pond, followed by another pond continuing the oxidation treatment and acting as a separator between the first and three others used for fishing and boating.

In the final lake, a swimming area is supplied with treated water recovered from sewage. Total water area in the five lakes is 30 acres, present land area in the park adds another 15 acres, and there is a total potential of about 300 acres.7

Open space around medium- to high-intensity residential uses and common open space in planned residential developments may fit well into the buffer greenbelt. In the neighborhood pattern discussed later, multi-family, townhouse, and similar forms would profit from location close to commercial and service facilities, from direct access to major open space, and from pedestrian ways with few or no vehicular interruptions.

Where the buffer must be narrow, townhouses or apartments constructed and oriented for noise resistance bordering relatively limited green space may be an answer. In more favorable circumstances, a high-rise bordering the park may considerably broaden it by merging its own green area with the strip.

Even in low-intensity areas, there are opportunities for broadening the scope and increasing the effectiveness of the open space system. As an example, in the Upper Rock Creek watershed in Montgomery County, Maryland, a stream valley public park is adjoined by largely undeveloped private lands which include tributary ravines and steep slopes unsuited for construction before rising to land well adapted for development. Here a logical solution would be to encourage planned residential development with common open space in the rough areas merging with the public park. This would protect lands highly susceptible to erosion, increase the visual effectiveness of the open space system, and provide easy access to the park from the planned developments.

In brief, there seems to be no shortage of uses adaptable to building buffer and border portions of the open space net. Anything providing (and requiring and benefiting from) substantial open space may be considered for inclusion, and the variety of opportunities within an urban area is such that careful planning should indicate an appropriate place and design for almost anything which would build the net.

Once the principle of the net is accepted as a basic consideration in planning, public uses can be located within it by direct public action. Quasi-public and private uses can be directed into desirable complementary patterns by a combination of regulation, the built-in inducement of advantageous location, and certain added attractions justified by both public and private interest. Before discussing implementation on the quasi-public and private fronts in detail, it is necessary to discuss some changes in neighborhood patterns which seem likely to follow as a result of application of the open space net concept.

THE NEIGHBORHOOD REVISITED — BY THE FAMILY CAR(S)

The American wife and mother, in her role as taxi driver, often feels that nothing is near anything or on the way to anything else. Any thoughts she may have about planners in this regard are likely to be unkind.

There is reason for her distaste. Planners have virtually ignored her. The literature is full of all kinds of origin and destination studies except the one which traces the devious journey of the family car on its daily round (or family cars — having more than one may be evidence of urban disorganization rather than affluence).

Enough evidence can be supplied from personal experience to make the main point. Father to work (by car 1 or aided by Mother's Taxi Service to work or to station). Children to schools — elementary here, high school there. Meeting at church. Shop. Pick up shoes left for repair. Something Committee lunch at civic center. Children from school — John to Little League Park, Deborah to Girl Scouts. Father home from work. Evening social or recreational travel.

The pattern will vary from family to family, from city to city, from central city to suburb. It will usually have one identifying characteristic — the destinations look as though they had been established with a shotgun. The elementary school is here, the high school there, the church in another direction, shopping and service facilities someplace else, and so on. And the random pattern often defies any linear shortcuts by which a number of places often visited could be reached along a single reasonably simple and direct route.

Considering the "neighborhood" in relation to the family automobile, social trends, planning theory, and the possibilities of the open space net, what improvements are possible?

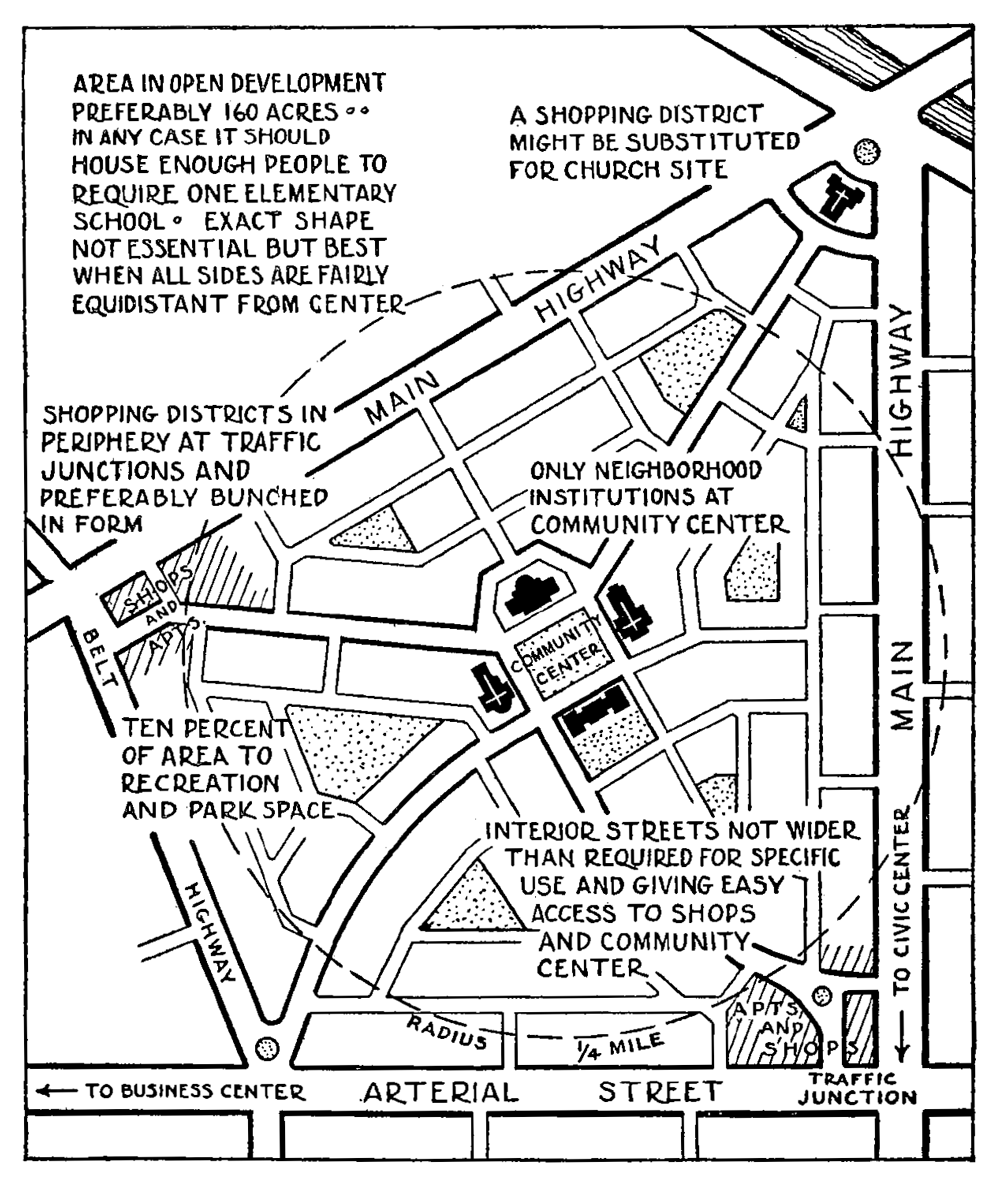

Planning Advisory Service Information Report No. 141, Neighborhood Boundaries, (December 1960) surveys the neighborhood concept as it had evolved to that point. Crediting Clarence A. Perry with the origin of the generally conceived neighborhood prototype in a 1929 New York regional plan report,8 this survey states that its six basic principles were:

- Major arterials and through traffic routes should not pass through residential neighborhoods, but should provide the boundaries of the neighborhood.

- Interior street patterns should be designed to encourage quiet, safe, low traffic volumes to preserve residential character.

- Population should support its elementary school (about 5,000 persons when Perry formulated his theory; in 1960, "current elementary school size standards probably would lower the figure to 3,000–4,000 persons"). (What happens in the future, with changing standards and perhaps elementary campus-type facilities?)

- The neighborhood focal point should be the elementary school centrally located on a common or green, along with other institutions with service areas coincident with neighborhood boundaries.

- Radius of the neighborhood should not exceed 1/4 mile, the maximum distance a child should walk to school. "Perry calculated that an area of about 160 acres would adequately house the elementary school supporting population in detached single-family residences on 40 by 100 foot lots, provided a small proportion of the people lived in apartments bordering the shopping districts. Current practices of making larger individual lots, and proportionately lower population densities, have increased the 'standard' neighborhood radius to one half mile."

- Shopping districts should be at the edge of the neighborhood, preferably at major street intersections.

Perry's neighborhood unit appears as Figure 2. Given the kind of travel schedule assumed for the family car, the trip pattern is likely to be scattered.

Figure 2. The Neighborhood Unit as Seen by Clarence A. Perry. Reproduced from New York Regional Survey, Volume 7.

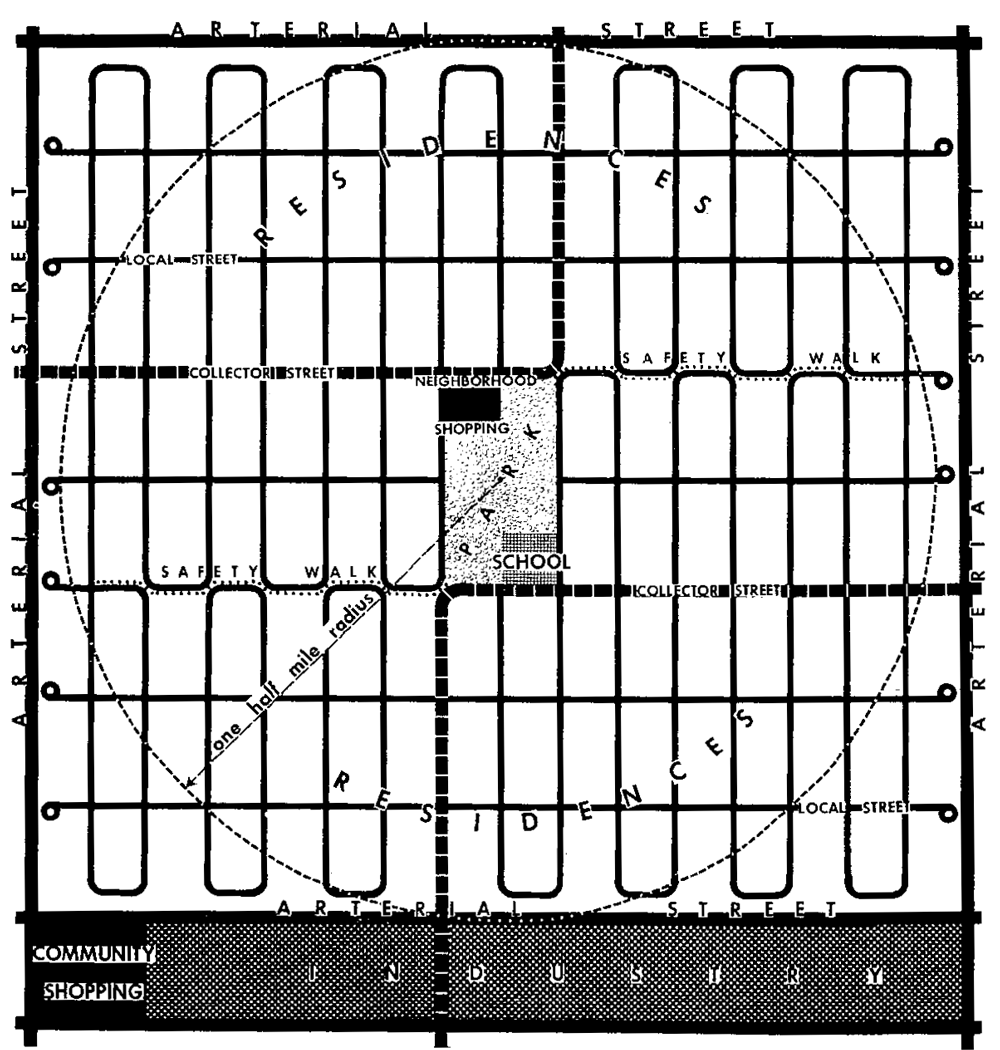

As one more recent example Figure 3 comes from Minneapolis and indicates a pattern adaptable to old grid patterns. Here the neighborhood radius has been raised to half a mile, with population indicated at 5,000–10,000, "large enough to support an elementary school." Walking distance to school has apparently doubled, and some "safety walks" have been provided, although most children walking would have to cross several streets. Again it is clear that the daily driving pattern might be rather erratic and it would certainly be circuitous for some residents. Follow a resident in the lower right corner to school and then to the neighborhood shopping center in the middle.

Figure 3. The Neighborhood Area. A sound area for living with: (1) adequate school and parks within a half mile walk; (2) major streets around rather than through the neighborhood; (3) separate residential and nonresidential districts; (4) population large enough to support an elementary school, usually 5,000 to 10,000 people; (5) some neighborhood stores and services. From Comprehensive Planning for the Whittier Neighborhood, Minneapolis City Planning Commission.

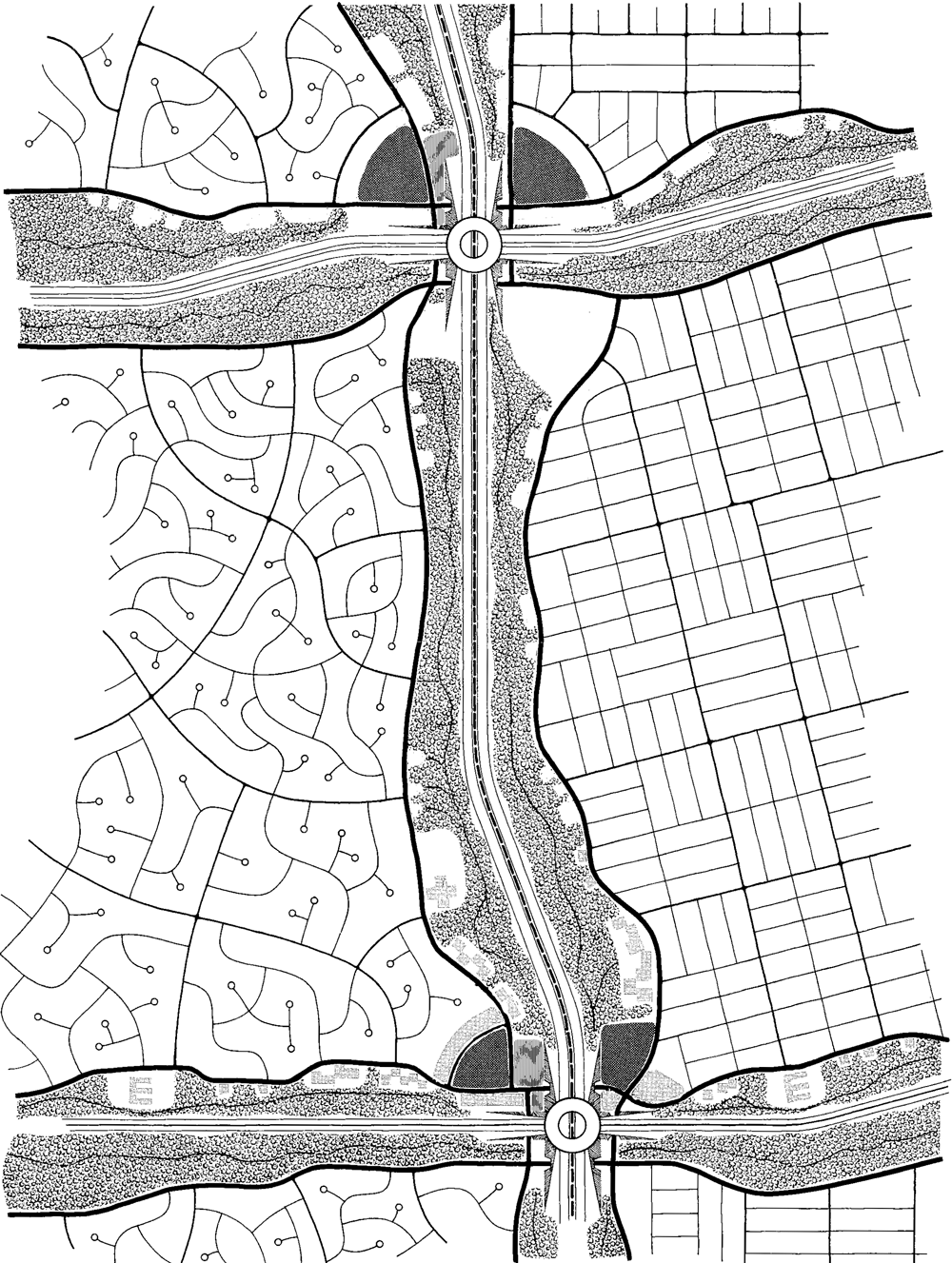

Figure 4, an approach better adapted to the automobile, is for new development. It would obviously not fit for reworking old gridiron neighborhoods unless there was complete redevelopment.

Figure 4. Neighborhood Unit Principles. Source: The Community Builders Handbook, Urban Land Institute, Washington, D. C. 1960. p. 79.

The principles stated remain similar to Perry's, but the pattern differs from his in many ways. Perry had scattered small parks. The Urban Land Institute proposes consolidation. Perry's combined apartments and shops seem to be a minor and incidental consideration and are not shown as concentrated in what would now be considered the prime corner. In the more modern plan, although a minor shopping area appears at the upper right, the "strong" center and major apartment concentration is toward what seems to be the direction of the CBD.

"Neighborhood" Principles and the Open Space Net

The net offers new possibilities for gradual rebuilding of old "neighborhoods" (however called — residential units, development areas, service areas, or by other names), and for shaping new ones. Some accepted principles remain unchanged by the net proposal, others are challenged. Using the format of the Urban Land Institute illustration and notes, considerations on the neighborhood within the net would be as follows.

1. Size. The elementary school is losing its magic as a prime determinant of optimum neighborhood size and population. The family automobile and the school bus diminish the importance of walking distance to school as a criterion for school location or neighborhood extent. There may be continued gradual increase in the size of elementary schools as individual establishments, and there is at least strong possibility of super-consolidation in the form of campus-like school facilities.

The elementary school may also be losing its assumed importance as a rallying point for neighborhood identification, loyalty, and social action. This is particularly likely to happen if cross-bussing between school areas becomes common as a means for encouraging wider range of social exposure or if campus-type facilities become widely used.

Thus in the long view it might be better to consider optimum "neighborhoods" as service areas with populations sufficiently large to require and support a variety of both public and private services which could not be provided efficiently for smaller units. Until circumstances alter, the elementary school might well remain as one consideration, but it would be prudent to go beyond it and include some other things — the branch public service center, providing some localized city hall functions, fire and police protection, the branch library, the health clinic, general welfare services, and so on. The optimum "neighborhood" should have a population large enough to support its own shopping and commercial service facilities.

Obviously, the pattern of the open space net will not always produce optimum residential neighborhoods. Where the physical area set off by the net is small, it may be that concentration of relatively high densities will provide the necessary population, or that special attention should be paid to designing easy access to facilities in adjoining areas.

At the other extreme, areas too large to be served conveniently by one set of facilities might have secondary groupings of their own to be tied by easy access from more remote sectors to facilities in adjoining areas. Planning principles related to the net approach provide logical locations both for supplementary facilities in the same service area and for interconnections.

Such overlaps in areas larger or smaller than the optimum would to some extent reduce the sense of identification, place, and proprietorship resulting from facilities primarily for the service area and located within its boundaries. As a practical matter, this may be a marginal consideration. Most "neighborhoods" will provide their own facilities, or enough of them to serve as a focus. And there appear to be many people who are not greatly concerned about a sense of place and proprietorship so long as facilities are adequate and reasonably accessible.

2. Boundaries. It is accepted doctrine that major arterials should bound rather than pass through residential neighborhoods. As has already been made clear, the net concept adds the provision that the arterials should be limited access wherever possible, with buffer greenbelt added by systematic location of bordering uses requiring substantial amounts of open space.

3. Open Space. Perry's diagram (Figure 2) indicates 10 per cent of the area of the neighborhood in recreation and park space, shown as a central community complex plus scattered small pieces for parks and recreation. Urban Land Institute, in Figure 3, calls for a central site for the schools and other service institutions, with a "small park and recreation site" for open-space surroundings. The open space net approach would combine school, park, and other substantial open spaces (including private) in the greenbelt buffer at the edges of the neighborhood.

4. Institution Sites. Perry and Urban Land Institute center the site for schools and other institutions. The net concept has such uses between perimeter streets and the limited access highway, adding their land to other open space forming the buffer, and so located as to provide safe access for pedestrians in a position to use the greenbelt and to facilitate automotive movements in a pattern well related to daily trips.

5. Shopping Center. The shopping and commercial service area remains at the prime corner as indicated by Urban Land Institute.

6. Residential Types. The ULI illustration has no specific notes on distribution of residential types, but the diagram makes the proposed pattern clear. Under the net concept, apartment locations would tend to concentrate along the greenbelt side of the border streets rather than forming a deep arc into the neighborhood as shown in the ULI plan. Some apartments might remain across the street from the shopping center, but it would seem preferable to provide for transition between the shopping center area and single-family detached sectors by townhouses, offices and other public and private uses not requiring major open space and held reasonably low to avoid visual friction with the single-family detached area.

7. Internal Street System. Certainly the principle remains valid that interior streets should have good access to major arteries and discourage through traffic. All three of the plans used for illustration of neighborhood principles have street layouts which accomplish this objective with varying degrees of success. But the treatment of the neighborhood central area in each requires running collector streets through the interior of the neighborhood.

The open space net "neighborhood" moves principal collectors to the edges, eliminating even more traffic from neighborhood interiors and making a more convenient, better coordinated origin and destination pattern for daily trips. Even where existing collector roads remain, provision of new ones in the peripheral area during transition to full net potential would reduce interior traffic.

Schematic Illustration

Figure 5 is an intentionally generalized and schematic illustration. It shows what might happen as a result of application of the open space net concept as limited access arterials cut through predominantly residential neighborhoods, and as complementary uses, open space, and principal peripheral collector streets are added.

Figure 5. The Net and Neighborhoods.

Given a web of limited-access highways, interchange locations are key influences in neighborhood orientation. Four neighborhoods cornering at an intersection will usually not have the same design or facilities in relation to the corners because of the influence of direction of principal traffic flow toward major destinations in the morning, home from them in the evening. Each neighborhood will have one prime corner, toward principal destinations, and some will have more than one.

Of four neighborhoods cornered on an interchange, only two will normally have prime corners in that location. In terms of morning traffic flow, these will be "downstream." The remaining two will have their prime corners further toward mass destinations. In the diagram, "downstream" is toward the bottom of the page.

The two prime corners would have principal neighborhood shopping centers and other neighborhood service facilities for the areas they serve. The other two quadrants are available for supplementary facilities for their own neighborhoods, or for uses serving several (as for example a high school or a hospital).

This pattern suggests certain design requirements. In most cases there should be direct cross-connection at interchanges between the principal neighborhood streets bordering the net. This facilitates interneighborhood flow of local traffic without loading the limited-access system with short-trippers. It should not be necessary to swing onto the interchange to do comparison shopping in an adjoining commercial district or to reach a nearby high school, hospital, or other interneighborhood facility.

Where mass transit (indicated by the black dashed line down the center of the diagram) is part of the limited access system, stations should be in or close to the interchange to improve coordination of multiple-purpose trips for driver-commuters or for those taxiing commuters, and to consolidate commuter parking with other parking in the vicinity where this might increase efficiency of parking use. In some instances, commuter parking might be within the area or structure of the interchange itself.

As related to shopping centers, street design near the interchange should be so arranged that it is possible for drivers either to visit the center and its related services area or to bypass with a minimum of friction. The center should not interfere either with cross-connections to adjoining neighborhoods or with access to the interchange.

(It should perhaps be reemphasized that Figure 5 is schematic, intended merely to convey the general idea. No scale is given, specific building types are not identified, and the grid and curvilinear street patterns are as stylized as the tree symbols — which indicate only the open space within the net, and not that it is necessarily wooded. From the preceding discussion, however, it should be possible to detail the relationships.)

NOTES ON IMPLEMENTATION

A number of actions toward building the net have already been suggested or implied, or become obvious when the principle is understood. This section reviews general types of implementation and proposes a few specific techniques.

The Comprehensive Plan

The comprehensive plan is obviously the place to start, since it states public intent and policies and lays the foundation for direct public action and for regulatory guidance of private action. Within the limits of current knowledge and foresight, the net should be generally located and dimensioned on the plan. Prime and other interchange locations should be identified in relation to service areas. The proposed interior pattern of the net (including uses in border and buffer sections) should be related to nearby uses outside the net.

From these initial efforts, necessarily fragmentary in some respects, it should be possible to assess priorities for needed action. With the net made part of the plan, next steps include detailed planning and programming for related public development, education to encourage public and private net-building moves, and specialized adaptations of the regulatory structure.

The long-range goal is to be achieved by short steps, of which the first should demonstrate that progress can be made and that the net is workable and has substantial advantages over more accustomed ways. Thus development action should start with what the military calls targets of opportunity, where current or impending programs are best adapted to achievement of net purposes. As examples, such demonstration sections might be created adjacent to new limited-access arteries, in connection with extensive redevelopment, or in open outlying sectors where it would be easiest to shape the emerging development pattern.

The planning commission has obvious leverage on items which they are required to review for compliance with the comprehensive plan, under relatively standard enabling requirements that after the plan has been adopted, "thenceforth no street, park, or other public way, ground, place or space, no public building or structure, or no public utility, whether publicly or privately owned, shall be constructed or authorized until the location and extent thereof shall have been submitted to and approved by the planning commission."

The scope and effectiveness of this power varies considerably. As examples of problems, school boards may be independent of local government. State or federal highway planners may ignore local plans, as may also special authorities of some kinds. "Higher" levels of government may pay no attention to local plans or regulations in locating structures and uses for performance of their governmental functions. In these cases, convincing persuasion may offset lack of direct control.

The Official Map

Where state enabling legislation is adequate, the official map may be helpful in locating and holding future rights of way, in establishing a base for special zoning or subdivision requirements for net-related lands, and for other purposes. Effectiveness depends partly on how and how long lands may be reserved for public use.

The Capital Improvement Program

In both its inclusive long-range aspects and in shorter-term capital improvement budgets, the capital improvement program offers recurring opportunities for providing and timing public improvements related to the net.

Zoning, Subdivision Regulation, and Supplementary Public Action

Regulations can include a number of techniques for promoting appropriate development of and beneficial additions to the net, but there are limits to what regulations may be expected to do. Direct public action is often required as a supplement.

Buffer-border strips, particularly in areas not under direct public control, will be of major regulatory concern. In generally residential areas, the solution is probably special zoning for districts usually including all land within the border streets, and sometimes land across the border street from the net. Some effects of this zoning will carry over into subdivision regulations automatically, as in the case of lot sizes and dimensions.

Prefacing provisions dealing generally with such districts, a declaration of intent should state purposes, desired effects, and design relationships. Detailed regulations for buffer-border districts will vary according to location in the urban and urbanizing pattern, existing and proposed land uses in adjacent areas and in the strips, and other special considerations.

Adjacent to the border street, structures and intensive uses such as major parking areas should be restricted to a relatively thin strip in areas where sizeable buffering is proposed. Setback from the border street should be adequate to assure safe and convenient access, but if held to reasonable minimums will increase the amount of interior space available for inclusion in the greenbelting.

The width of the buffer might be specified as a set distance, as a proportion of the depth of the lot between its front and the right of way of the limited access facility, or as a rear building line established on the zoning map.

Access to and through the greenbelt is important. In part, this access should be visible, in part pedestrian.

Much of the visual access from the perimeter street and property across it will be lost if it is blocked off by an unbroken structural wall of border uses. Zoning requirements for side yards will help, but should be supplemented by public action to provide uninterrupted exposure to the park in some areas, public parking areas along the border, and careful orientation of public buildings on their lands.

Pedestrian access to and through the greenway might be handled in part by subdivision requirements including public access easements under specified circumstances (perhaps combined with utility easements in some cases). Since action in building the net will often involve at some stage public ownership of at least strips of the land nearest the freeways, pedestrian ways might be designed and maintained in such locations as part of the redevelopment program. Given provision for pedestrian circulation as a stated part of the intent of the open space net plan, outright purchase or condemnation of title or easement for pedestrian use might be appropriate. And where rights-of-way for freeways are wide enough, there seems no reason why pedestrian ways might not be located along their outer fringes.

In outlying sectors through agricultural areas, if the strip can be located in advance of intensive development, land within it might be held in agricultural zoning with the proviso that it could be used for other than agricultural purposes only through planned development rezoning according to specified standards, and with uses and intensities as indicated in the comprehensive plan (which should in such case indicate prospective uses and intensities!). This gives maximum opportunity for public-private cooperation to assure solutions hand-tailored to local circumstances, and would probably present no legal difficulties if the provisions were carefully drafted and intent persuasively set forth.

Planned developments adjacent to the net, or in its fringes, should be encouraged to incorporate or merge their common open space with the buffer greenway, to maximize visual impact, and increase accessibility and utility.

At interchange locations, prime and otherwise, boundaries for neighborhood shopping and office districts and for districts for interneighborhood public, quasi-public, and private major service facilities should be drawn to fit the cases and, if at all possible, only planned development should be permitted. One solution here would be acquisition of title or use rights by the public, covering the areas involved beyond the limited access and interchange rights of way, with passage of title or use rights into private hands only subject to planned development. Few localities are as yet in a position to move generally in this direction for legal, procedural, and financial reasons, but it seems inevitable that the time must come. When the situation has deteriorated to the point where urban renewal is justified for the entire area, the time has come.

Greenway uses close to interchange locations can be controlled with the stick, the carrot, or both. Near prime locations, the stick approach would prohibit uses which might be better located elsewhere, and would also permit certain uses desired within the greenbelt only in such locations. The carrot approach might take several forms. For example, uses permitted elsewhere only by special exception or other extraordinary procedures might be permitted by right only within the strip. Lot area requirements within the strip might be set somewhat lower than generally on grounds that proximity to permanent open space reduces need for lot size. As a case in point, a church might be allowed on three acres in the greenbelt rather than five elsewhere.

For multi-family uses, a provision with the same effect but stated differently might be effective. In connection with its land-use intensity rating approach, FHA allows extra floor area ratios where lands adjoin appropriate permanent open space. Thus a multi-family structure located within the net would get extra floor area. The special zoning regulations for net districts might specify that multi-family uses would be allowed only in specific delineated zones within the net, but that in such districts the extra floor area would apply.

Beyond the Local Scene — Federal Programs

Fruition of the open space net principle can be hastened by astute use of federal programs already in being, and further encouraged by new adaptations.

It is beyond the scope of this report to explore these possibilities in any depth, but with focus on the net idea it is apparent that among others, urban renewal, open space, public facilities, planning and perhaps even Model Cities funds might be effectively used. And given federal interest in the apparent advantages and economies of the net system, requirements and rewards recognizing the approach might stimulate better and faster net planning and development by such means as bonuses for location of mass transit in linear cores or increases in share of federal aid where the open space net is a goal in planning.

If the open space net concept can be incorporated into local planning even in the form of a relatively limited experimental demonstration, it seems highly probable that with the right start and continued public guidance and support the net should grow and spread under the impetus of its own merit.

ENDNOTES

1. Gallion and Eisner, The Urban Pattern. New York: D. Van Nostrand, Inc. 2nd ed. 1963, pp. 81–2.

2. "Planning Ahead — Adventures in the Unexpected Obvious," by Frederick H. Bair, Jr. Florida Planning and Development, January 1962, p. 5.

3. "Future Town Forms — A Matter of Choice," by Frederick H. Bair, Jr. Florida Planning and Development, October 1965, p. 5.

4. "Open Spaces in Urban Growth," S. B. Zisman, Proceedings of the 1964 Institute on Planning and Zoning, The Southwestern Legal Foundation, Dallas. 1965, Matthew Bender and Co., Albany, N.Y. The paper contains an excellent summary compendium of recent thinking on urban open space.

5. Prospectus for Cooperative Research, American Public Works Association Research Foundation, APWA, Chicago. 2nd ed. 1967. See particularly "Project 66-4, Better Utilization of Open Space," pp. 37-40. As background, see also Better Utilization of Urban Space, Summary of a Symposium on Research Needs, APWA, 1967.

6. Urban Systems Engineering, an Advisory Report to the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Department of Civil Engineering, The Technological Institute, Northwestern University, Evanston, Ill. 1967. pp. 21–22.

7. "Reclaimed Wastewater for Santee Recreational Lakes," John C. Merrell, Jr. and Albert Katko, Journal, Water Pollution Control Federation, August 1966, pp. 1310–1318. See also "Reclaimed Sewage Becomes a Community Asset," John C. Merrell, Jr. and Ray Stover, American City, April 1964.

8. "The Neighborhood Unit," Neighborhood and Community Planning, VII, Clarence A. Perry, Committee for the Regional Survey of New York and Its Environs, 1929.

Prepared by Frederick H. Bair, Jr. Copyright 1968 by American Society of Planning Officials.