Planning the Airport Environment

PAS Report 231

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear. Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

More From APA

Interested in Airports? You might also like:

Planners and Planes: Airports and Land-Use Compatibility

Airport planners and community planners must work together as partners during the development of planning processes in order to weave a community's vision, strategies, and values together with those embedded in airport planning.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 231 | February 1968 |

Planning the Airport Environment

Download original report (pdf)

Over the last 10 years the air transportation industry has maintained a growth rate substantially higher than that of the rest of the economy, largely due to the introduction of jet aircraft into commercial air transportation. This revolution in air travel is likely to continue at an accelerating pace, with dramatic effects on travel habits, ways of conducting business, places to live, work, and visit — and on the need for air transportation facilities. When the aircraft now being developed go into active service, most existing facilities, from air terminal buildings to air navigation aids, will become obsolete.

Some of the new planes will be larger. The "stretch" model of the DC-8, capable of carrying up to 250 passengers, has already gone into limited service. Within two years, the Boeing 747 "jumbo jet" with a capacity of up to 500 passengers will be introduced, and by the mid-seventies, planes carrying up to 700 passengers may begin to serve major cities. Even larger planes (such as the 900-passenger Lockheed L-500) are on the drawing boards.

Some planes will be faster. Supersonic transports capable of flying at three times the speed of sound may begin operating by the mid-seventies. In addition, smaller, short-range, subsonic jets and large-capacity air buses for high density routes will be introduced, both more efficient than present aircraft. Vertical/Short Takeoff and Landing Vehicles (V/STOLs) may be developed for commercial use. If their undesirable operating characteristics can be eliminated, such aircraft may be operated from terminals close to city centers.

Finally, the growth rate of general aviation, i.e., business and other noncommercial aircraft, is expected to continue to exceed that of commercial airlines. Currently, 97 per cent of all aircraft (other than military) is in the general aviation category.

Among the important consequences of the use of these new aircraft are the following:

- Increased passenger capacity will produce operating economies which may permit fares to be reduced by up to 50 per cent depending on the length of the trip. With lower fares and higher family income, the 5 per cent of the population that now flies regularly may increase to 10 per cent or more.

- Many airport facilities now in use, including runways, taxiways, aprons, and terminals will become obsolete because they will be unable to handle increased aircraft weight and passenger volume.

- Many new aircraft will be designed solely for freight; others can be quickly converted from passenger use during the day to freight operations at night. Air freight shipments will continue to increase as air cargo capacity improves the competitive position of airlines vis a vis railroads and trucks.

- Short-range jets will increase the number of cities served by jet aircraft. The number of jet airports is expected to increase from approximately 112 now to about 350 by 1970.1

- Increased capacity and speed and lower costs will result in increased person-to-person contact, will open up new markets by making products more accessible, speed mail delivery, and raise the number of conventions and conferences being held.

Predictions are difficult, especially as to the effects of new technology, but it is safe to say that the impact of the new equipment on patterns of air travel, which in turn may affect the form and structure of cities and metropolitan areas, will be substantial.

There is indeed evidence now that air transportation is beginning to exert an influence on metropolitan structure. Many of the largest airports are already the focus for a variety of commercial activities and are becoming increasingly important in determining industrial location. If this trend continues, as is expected, airports and their surroundings may become centers of economic activity of major importance resulting in as yet unforeseen changes in existing land-use patterns. While this report is concerned particularly with development in the immediate vicinity of airports, the effects of this development on the entire form and structure of the metropolitan area must also be considered.

The purpose of this report is to summarize the major problems which must be dealt with by planners concerned with existing airports or with proposals for new airports, and to suggest a variety of methods and tools which can be used to achieve an environment compatible with airport operations. Its main thesis is that airports, especially jet airports, merit special attention in the planning process because of their enormous positive and negative effects, and that a variety of methods must be employed to deal with them.

In the following sections, the airport is viewed from three different vantage points: as a transportation facility; as a nuisance, primarily because of the noise and the air crash danger associated with it; and as a land use influencing other land uses. Because most of the factors associated with each of these views cut across existing governmental boundaries, a fourth consideration is discussed: the airport as an interjurisdictional concern.

Airports as Transportation Facilities

The National Airport System

The national civil air transportation system is the direct concern of two federal agencies: the Civil Aeronautics Board and the Federal Aviation Administration of the Department of Transportation (formerly the Federal Aviation Agency). The CAB is primarily concerned with regulating commercial air carriers, including establishing fares and determining airline routes, and also with the promotion of safety in civil aviation. The FAA has the following responsibilities2;

- Safety Regulation. Certifies airmen; develops safety regulations for the manufacture, operation, and maintenance of aircraft; performs flight inspection.

- Research and Development. Develops and evaluates navigation and traffic control procedures and facilities; assists in the development of improved aircraft and aircraft engines. (The FAA is playing a major role in the development of commercial supersonic transports.)

- Establishing and Operating Air Navigation Facilities. The FAA is responsible for all aspects of air navigation aids, including air traffic control equipment.

- Airspace Control and Air Traffic Management. Develops air traffic rules and regulates all aspects of the navigable airspace.

- The Federal-Aid Airports Program (FAAP). Implements the Federal Airport Act by providing grants-in-aid for the development of public airports (See Appendix A); establishes standards for airport development and fosters the development of a national system of airports. The FAA annually publishes the National Airport Plan (NAP) which lists all airports, heliports, and seaplane bases which comprise the national system and projects the need for airport facilities for a five-year period. (Privately owned airports are included although they are ineligible for aid under the FAAP.) It should also be noted that FAA cannot enforce its standards except as they are prerequisites for federal aid.

Air Transportation in the Local Transportation System

The airport is one of the largest local traffic generators in most metropolitan areas. On the average, about 60 per cent of air passengers use private automobiles, 20 per cent taxis, l2 per cent limousines, and about 8 per cent public transportation. Airports also have a considerable amount of truck traffic. Airport-generated traffic in combination with other traffic often creates congestion on access roads, thereby increasing the total time of the air travel trip. Because sites for new jetports require huge amounts of land and relative separation from surrounding development, most will be constructed at some distance from population centers with a corresponding increase in the ground transportation problem.

The FAA has called ground access one of the "critical imbalances" in the air transportation system and has encouraged a systematic approach to transportation planning in order to reduce total travel time. A number of novel and not-so-novel approaches for relieving ground transportation congestion have been suggested, some of which are currently being tested.

One proposal applicable to larger cities is connecting the airport to the city by a rapid transit rail line. In Europe, Brussels and London have rapid transit airport connections; in this country, Cleveland is currently extending its subway line to Hopkins Airport with several other cities contemplating similar steps. So far, rapid transit service to airports has failed to gather wide support because (1) it may not be economically feasible unless it can serve other activities along the same line; (2) passengers may be unwilling to carry their bags onto a subway or train; (3) many airline passengers begin and end their trips at scattered residential locations rather than downtown.

On the other hand, many airport-serving roads are reaching their design capacity, particularly since the peak commuting hours tend to coincide with peak flying periods. Second, parking facilities even at many smaller airports are filled to capacity much of the time. Third, rapid transit could bring passengers directly into the terminal rather than to a parking lot.

It was long thought that helicopters would play a major role in providing access to the airport. However, to date they have failed to fulfill their expected role and are operating only in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, with an application pending before the Civil Aeronautics Board to establish an airline-subsidized helicopter service connecting Washington and Baltimore with their airports. The use of helicopters may increase somewhat in the future, but they are likely to continue to require some form of subsidy.

An interesting proposal currently being tested is the helicopter-borne sky lounge which had its first experimental flight last summer. The sky lounge, built by Philadelphia's Budd Company for the Los Angeles Department of Airports, is a bus-like vehicle which would pick up passengers at hotels or other points in the city and take them to a central helicopter terminal from which it would be airlifted by the Sikorsky YCH-54A "flying crane" to the airport.

The Airport Nuisance Problem

Nuisance is used here in a broad sense to connote such effects of the airport on its surroundings as noise, crash hazards potential, and air pollution as well as the effects of neighbors on the airport that limit its safety and efficiency.

Noise

Noise is the most pervasive of the environmental effects of airports and has proved to be the most difficult problem to solve. The reason is summed up in the following: "Contrary to all the noise about noise, it is not a problem of technology. For all practical purposes technology has failed. You just can't release that much energy without making one hell of a lot of noise."3 As a result, "aircraft noise is a problem for which there is [not] as yet. and may never be, a single solution of demonstrated feasibility."4

It has been demonstrated, however, that a combination of tools can be used to reduce the impact of noise. Appendix B contains a brief introduction to the problem of noise (and its terminology) and suggests a method for applying noise measurements to land-use planning. Reference is also made to several of the publications listed in the bibliography.

The following classification of noise reduction "components" is useful for planning purposes.

Reduction at the source — Improve engine design and use sound suppressors and absorbers.

Reduction in the transmission medium — Increase the distance between source and receptor and use sound-absorbing materials and techniques in construction.

Reduction at the receptor — Reduce the concentration of people in noise-affected areas.

The FAA, in consultation with a number of other federal agencies including the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and HUD, is conducting research into means of noise reduction at each of these points, concentrating primarily on (1) engine and airframe design; (2) flight operation procedures and techniques; and (3) compatible land-use planning in the vicinity of airports, with some research also into structural noise-reduction methods. (Sonic boom is an additional, perhaps even more vexing problem, which should be dealt with before the introduction of supersonic aircraft in the 1970's.)

Crash Hazards

A second reason why airports are considered to be undesirable neighbors is the fear of crashing aircraft. The 1952 report of the President's Airport Commission (The Doolittle Commission), The Airport and Its Neighbors,5 remains the most definitive study of this problem. The Commission found that most aircraft crashes occur in a direct line within one-half mile of the end of runways. Beyond this point, accidents occur in a more random pattern.

Part of the reason for the low number of nonoccupant aircraft crash fatalities may well be that a principal recommendation of the Doolittle Commission report, the establishment of clear zones off the ends of runways, has been followed. In fact, such zones are mandatory at all airports receiving aid under the FAAP program.

The following table shows the relative insignificance of the number of people killed by aircraft (excluding vehicle occupants) as compared with those killed by other vehicles:

Table 1

| Transportation Nonoccupant Fatalities, 1950–1963, by Mode | |

| Automobiles | 121,853 |

| Railroad Passenger Trains | 12,830 |

| Buses | 4,908 |

| Scheduled Air Carriers | 41 |

Source: Special Subcommittee on Regulatory Agencies of the U.S House of Representatives Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, Investigation and Study of Aircraft Noise Problems, H. Rept. No. 36, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963), p. 25.

Community fear of aircraft crashes is closely associated with noise. Horonjeff, in his Planning and Design of Airports6 indicates

. . . that reduction of aircraft noise reduces the number of complaints regarding airport operation and that fears of low-flying aircraft and of property devaluation, an indirect measure of nuisance and hazard, are both associated with noise.

Air Pollution

Although findings with respect to aircraft-generated air pollution are not yet conclusive, some studies indicate that jet aircraft emit substantial amounts of carbon monoxide and oxides of nitrogen during landing and takeoff. Relative to the total amounts of these pollutants in the air, such quantities may not be very significant, but in the vicinity of such heavily-used airports as O'Hare, Kennedy, and Washington National, they may cause some concern. The recently passed Federal Air Pollution Control Act provides authority to perform additional research.

Flight Interference

As noted above, the airport's neighbors can be a nuisance to the airport as well as vice-versa. In fact, until the Doolittle Commission report flight interference was the most important consideration. Even now, this is the primary concern of most airport zoning ordinances. Flight interference may take three forms: airspace obstructions, electrical interference with communication and navigation equipment, and obscuring of airport lights.

Airspace Obstructions. — There are few cases on record of airports having to close down as a result of the erection of tall structures in their runway approach zones, but at a number of airports pilots must exercise special care because of tall buildings.

Thus, one of the important criteria for selecting a site for a new airport is the nature and extent of obstructions, e.g., buildings, trees, and transmission lines, which would have to be removed. (Specific dimensional criteria are described in "Objects Affecting Navigable Airspace," Part 77 of the Federal Aviation Regulations. Removal of hazards or lighting of obstructions is an eligible cost under the Federal-Aid Airports Program.)

Electrical Interference. — Modern air traffic control requires the use of sophisticated communications and navigation equipment. In areas where air traffic is heavy, a breakdown of, or interference with, communications between the air traffic controller and the aircraft could be disastrous. It is particularly important that there be no interference with aircraft operating under IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) conditions, i.e., when weather so restricts visibility that electronic navigational equipment must be relied on exclusively until the aircraft is within a few hundred feet of the ground. Activities such as testing of electrical equipment which might interfere with communication between the airport and the aircraft should therefore be prohibited in specified zones. The FAA and the Federal Communications Commission coordinate their activities so that broadcast facilities at or near airports and airways will not interfere with aviation safety.

Interference from Lighting. — Provisions must also be made for preventing the operation of lights which would make it difficult for the pilot to distinguish between airport lights and others or which would in any way impair visibility in the vicinity of airports.

The Airport as an Influence on Land Development Patterns

Airports are beginning to play an important role in determining land development patterns. In the vicinity of major airports can be found an assortment of hotels and motels offering complete convention facilities including sleeping and meeting rooms as well as restaurants and entertainment establishments. Manufacturing plants and offices have found a location near an airport desirable because it offers fast delivery of personnel and goods. Some airports have developed "fly-in" industrial parks offering direct taxiway access to individual plants.

Enormous increases in the cargo-carrying capacity of aircraft as well as advances in packaging and loading systems will reduce shipping rates so that air cargo will no longer be confined to high-value commodities. Thus, warehousing facilities near airports may become more prevalent. Industries will find airport sites desirable because business-owned planes will be able to park at the door. (There are about 40,000 business-owned aircraft today with the annual number of aircraft purchases increasing greatly.)

Thus, although air transportation will probably remain a relatively small percentage of all intercity travel, it will exert a considerable influence. Concentrated development of commerce and industry may lead to "airport cities" in competition with existing central business districts. In-city hotels and related establishments catering largely to travelers may be most seriously affected, but even downtown retail businesses may feel the effects.

Airports also exert an important influence as a result of their size. In most areas the airport is the largest land use under single ownership. Proposed major jetports are expected to occupy 10,000 acres or more; the contemplated size of the new airport to serve Dallas and Fort Worth is 18,000 acres. In addition to land used for airport facilities, land is needed for clear zones. Finally, land will be needed at all new jetports to provide for potential expansion. In the past, expansion of many airports has been at the cost of numerous houses and other land uses because insufficient land was kept in reserve. The inability to extend runways was part of the reason for curtailment of service at Detroit's Willow Run Airport and at Midway in Chicago. Both were, in effect, "locked in" by existing development. New airports will need sufficient land to accommodate aircraft likely to become available in the foreseeable future to ensure their continued use.

The following paragraph summarizes the role of the airport in influencing land development patterns:

It is important to recognize that an airport is a causal factor, which can be used to direct, to focus, to guide and to create a business and employment center, to buttress and area's tax base, and to stimulate area development and commerce. Although an airport is an extensive land use, it generates an intensive land use around it. Thus, it is frequently argued that an airport should be moved out into the countryside, hoping to keep the land use around it extensive. Unfortunately, airport isolation simply does not work. An outlying airport either will become an air city and cause perimeter growth of population and commerce, or it simply will not be used. Thus, land use controls to protect the airport from its neighbors — and the neighbors from the airport — are mandatory.7

Airports and Intergovernmental Relations

All levels of government are now or are potentially involved in airport development because each of the elements noted above — transportation, nuisance, and land use — pays little attention to political boundaries, and because the direct or indirect costs of airport facilities are spread among governmental jurisdictions. Governmental coordination of airport-area planning is particularly difficult because the federal government is the source of most funds but has little power to influence directly land development patterns; local governments have fewer financial resources but have most of the land-use control powers; and metropolitan or regional authorities, perhaps the most logical bodies for airport planning, have neither the money nor the power. States have traditionally been uninterested in either planning for or financing airports, although there are a number of noteworthy exceptions.

The federal government's participation in airport development is limited under the Federal Airport Act to implementing the National Airport Plan. The FAA is not directly involved in broad areas of airport development, management, and operation. It becomes financially involved only at the initiation of the sponsor, and then only with specified elements within the airport's boundaries.

While the federal government has played a major role in expanding the national airport system through the FAAP, the local sponsors have retained virtually complete control of the airport facilities as well as of the areas affected by the airport and its operations.

Metropolitan and regional agencies have begun playing a more important role by preparing areawide airport system plans and, with the passage of the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966, by being granted the authority to review and comment on a number of proposals for public facilities of regional importance, including airports.

While at least 44 states have aeronautical agencies at the state level, only 16 provided funds to localities for airport development as of 1962.8 The Arthur D. Little study, Airport Land Needs, concluded that "it is likely that state aid for airports will amount to more than 25 per cent of total airport expenditures within the next ten years."9 Nevertheless, in the absence of effective metropolitan control over the area affected by airports, and in the absence of additional local funds for airport financing, the state is potentially the best level for designing and implementing a comprehensive development plan.

Planning the Airport Environment

Airport and airport-related developments warrant special attention in the planning process in order to achieve the following objectives:

(1) To take advantage of the impact of the airport on land development.

(2) To provide for quick and efficient access to the airport for all users.

(3) To minimize the nuisance effects of the airport on its surroundings.

(4) To minimize the restrictions placed on airport operations by surrounding development.

This section explores methods and techniques for achieving these objectives.

Airports and Metropolitan Planning

Many of the problems now being faced by airports and their neighbors have arisen because planning has occurred almost exclusively at the local government level. Yet, achieving the objectives requires transcending local political boundaries. A HUD official has described the "transcendentalism" of an airport as follows:

. . . airports are transcendental because their influence transcends the boundaries of the land they use, the cities they serve, and often two or more states. . . . The jet airport is transcendental also because its activities are not static, its influences are not easily measured or necessarily understood by the public, and because it is neither classified nor controlled conventionally.

The jet airport projects and attracts economic activities, which are generally regarded as beneficial. In this respect it is conventional. It also generates major volumes of traffic by conventional vehicles that readily cross the boundaries of conventional land use units and represent systems for the movement of people and goods to which the society has become accustomed. The distinguishing feature of the jet airport is that it also projects the invisible, but nonetheless real, influence of cataclysmic noise far beyond the boundaries of the land it actually owns.10

Insofar as it attracts economic activities and generates traffic by conventional vehicles, it is conventional, but the effects of the noise it generates are far from conventional and may have to be handled in unconventional ways.

McGrath also estimates that the number of people exposed to the severe noise levels of 100 or more on the CNR (Composite Noise Rating) scale is about 106,000 near Chicago's O'Hare Airport; 129,000 in the vicinity of Los Angeles International; and 108,000 around Kennedy in New York.11 In each case, many of the people live outside the sponsoring community. Thus, in order to have sound airport development, planning ought to take place above the local level.

As new jetports take at least five, and as long as 10 years to plan, design, and build, planning programs to provide for the jumbo jet traffic of the late 1970's should start now. FAA has continuously emphasized the need for integrated planning:

Airports in and around metropolitan areas must be planned and operated as a system so that their interactions are not detrimental to their capacities and so that their functions are complementary. Furthermore, as air traffic continues to increase, more of these airports will approach and exceed a practical operating limit. It is desirable, therefore, to plan each airport in a metropolitan area as a part of a system of airports in order to obtain the most efficient traffic flow and the most effective use of facilities.

Beyond the air traffic control problem, coordination of airport planning with other kinds of planning adds a new dimension to airport system planning. In metropolitan areas the demand for airports is both local and areawide. Planning for major commercial airports and small general aviation airports must be coordinated and integrated. Further, airport planning to be most effective should be coordinated with areawide highway and transit planning as well as land use planning.12

In smaller metropolitan areas, or nonmetropolitan areas, a single airport may adequately serve commercial carriers and general aviation. In addition, several cities may wish to consolidate their airports in a single facility if a suitable site can be found within reasonable distance of all. For example, commercial service to North Carolina's Research Triangle (Raleigh, Durham, Chapel Hill) is provided by a single airport. FAA's Advisory Circular, Regional Air Carrier Airport P1anning,13 provides guidance for evaluating the feasibility of establishing regional airports.

A systematic procedure has been developed by FAA for planning the metropolitan or regional airport system and for integrating it with other development plans. The procedure can be summarized as follows:

First, preparation of a long-range comprehensive plan including identification of areas which will need new airports; Second, preparation of a long-range airport system plan indicating generally where new airports should be located and where existing airports should be expanded; Third, preparation of a short-range comprehensive development program indicating the five-year development plans for highways, transit, open space, public utilities, land use, flood control and drainage for the metropolitan planning area; Fourth, preparation of a five-year airport development plan, including inputs from the long-range comprehensive plan, the long-range airport system plan and the short-range comprehensive development program. Each of these four basic parts of the metropolitan airport system study should be carried out concurrently and the "feedback" from each phase should influence each of the other phases.14

The Congress underscored the need for such areawide planning by amending the Federal Airport Act in 1964 to require that applications for federal airport aid contain evidence that the proposed project will be "reasonably consistent with existing plans of public agencies for the development of the area in which the airport is to be located," and, as noted above, by giving metropolitan agencies review authority over airport proposals.

Federal assistance for planning the airport system as well as for comprehensive planning is available through the 701 program. Assistance in the technical aspects of planning individual airports and the airport system and relating them to regional development plans is provided by the FAA through its regional offices and through a number of its publications. FAA also provides financial assistance for the design and construction of public civil aviation airports (see Appendix A).

Compatibility

The development of the concept of airport environmental compatibility has proceeded in several phases. Early interest was exclusively in protecting airspace approaches through height regulations and regulations on such uses as might interfere with navigation or pilot visibility. The 1952 Doolittle Commission report added a new dimension to the concept of land-use compatibility, that of protecting the airport's neighbors from the potential danger of aircraft crashes. The Commission recommended the establishment of clear zones off the ends of runways, preferably by land purchase, and called for land-use restrictions in a fan-shaped area beyond the clear zones "as a protection from nuisance and hazard to people on the ground." This controlled area would be at least two miles long and 6,000 feet wide at its outer edge and "no schools, hospitals, churches, or other places of public assembly," would be allowed. The preferred land use was agriculture, with housing recommended for the outer portions only.

More recently, especially with the introduction into regular service of the large jets, much concern has been shown with the effects of airport-generated noise on the environment and with means of channeling activities least sensitive to noise interference into affected areas. The Congress recognized a need for noise compatibility in the 1964 amendment to the Federal Airport Act by including the condition that

appropriate action, including the adoption of zoning laws, has been or will be taken, to the extent reasonable to restrict the use of land adjacent to or in the immediate vicinity of the airport to activities and purposes compatible with normal airport operations including landing and take-off of aircraft.15

The Congress thereby recognized that airports could affect land use in the entire airport environment.

In addition, the FAA has attempted to minimize noise effects through changes in aircraft operations including such noise abatement flight procedures as modifying the rate of descent and climb of aircraft, the application and reduction of power, changing the direction of flight paths, and establishing a system of preferential runways. The specific application of each of these procedures is described in Part 14 of the Federal Aviation Regulations.

In the last few years, as the airport has become recognized as a magnet for a variety of land uses, planning for airport compatibility has dealt with the need to provide for those activities best able to take advantage of proximity to the airport. The airport city idea has developed out of this approach. Consequently, two factors are now considered: (1) the need to prohibit those uses which are harmed by proximity to the airport and (2) to provide for those which benefit by such location. The first factor suggests excluding residences and places of public assembly from the immediate vicinity of the airport; the second suggests providing for such uses as airport-related industry, industries which do not interfere with flight operations, and airport-related or travel-oriented commercial activities, as well as open space. Fortunately, these factors are mutually supporting; those uses most attracted to the airport are those least bothered by the noise. In addition, such uses tend to raise land values and are desirable from a financial point of view as well.

Examples of Compatible Land Uses

As suggested by a number of airport area reports prepared during the last few years, there are four broad categories of land use considered most appropriate to the airport environment. These categories are:

(1) Open uses involving few people.

(2) Inherently noisy activities not sensitive to additional noise.

(3) Indoor uses which can be protected from airport noise by soundproofing.

(4) Airport-allied uses which have an incentive to locate close to the airport.

1. Open Uses Involving Few People

In the innermost areas of approach zones where overflights occur quite close to the ground, open uses and those which require relatively little construction can serve as buffers to minimize potential crash damage and to reduce the impact of noise. Such uses include:16

Natural-Corridor Uses

Rivers, lakes, and streams

Swamps

Areas subject to flooding

Other forms of unpopulated land

Open-Land Uses

Cemeteries

Reservoirs

Reservations

Game preserves

Forests

Water-treatment plants

Sewage-disposal plants

Sod farming

Truck farming

Other vegetable & plant crop cultivation

Landscape nurseries

Golf courses

Riding academies

Picnic areas

Botanical gardens

Passive recreation areas

Additionally, such transportation facilities as highways, railroads, and railyards might be developed separately or in conjunction with other open uses.

A report in the Wisconsin Development Series17 suggests that this list be qualified in several ways. Such uses as game preserves, swamps, and some forms of farming may attract birds which can be hazardous to aircraft operations. Some types of livestock may be raised in affected areas depending on the way they react to noise. Trees are desirable because they deflect noise away from more intensive activities. Finally, fear of crashes may make picnic areas undesirable land uses directly under approach zones.

A comprehensive program of public land purchase in the vicinity of airports can play an important role in removing the most severely noise-affected areas from possible development. As noted below, this has been done in a number of areas around the country. (Many such uses qualify for federal assistance under either HUD's Open Space Program or under the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation Programs.)

2. Inherently Noisy Activities Not Sensitive to Additional Noise

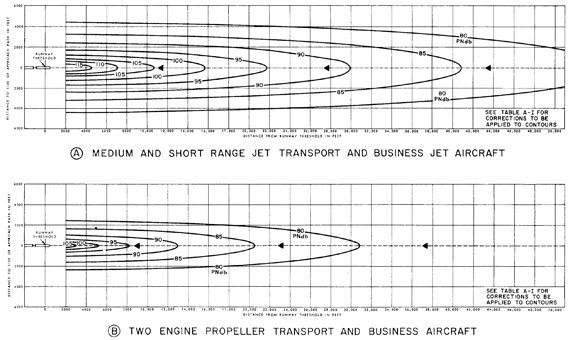

There are many industrial processes which operate under noise levels so high as to be little affected by the incremental increase as a result of proximity to an airport. Figure 1, reproduced from the Detroit report, was prepared after an extensive series of internal noise measurements by an acoustical consultant. It contains data which can assist in determining appropriate locations for generally noisy activities.

Before such an approach might be applied in order for these data to be of greatest value, it is useful to measure external airport noise and develop noise contour lines (see Appendix B) for each airport. As with other performance standards, the expertise required for their enforcement may present an additional problem.

3. Indoor Uses Which Can Be Protected from Airport Noise by Soundproofing

A report prepared for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration suggests the use of various types of building materials and construction methods to reduce internal noise levels. With respect to acoustical control in structures, it concludes that:

The average building offers substantial noise reduction if the windows are closed. Additional noise proofing can be added at moderate cost. Satisfactory interior noise levels can therefore be maintained even in severely noise affected areas.18

Table 2, adapted from the NASA report, was prepared on the basis of actual internal noise measurements as well as subjective judgment with respect to acceptable interior noise levels.

Figure 1

Source: Detroit Metropolitan Area Regional Planning Commission, Environs Study and Plan: Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport, Detroit, Michigan, May 1964, p. 42.

Table 2

Acceptable Exterior Noise Levels for Various Activities Based on Average Noise Reduction by Building

| Activity | Acceptable Interior Noise Level (PNdb)* | Acceptable Exterior CNR** (without modification) | Acceptable Exterior CNR** with 10 db extra Noise Reduction |

| INDUSTRIAL | |||

| Apparel | 85 | 115 | 125 |

| Printing | 80 | 110 | 120 |

| Food Processing | 80 | 110 | 120 |

| Metal Working | 90 | 120 | 130 |

| OFFICES | |||

| Private-one floor | 50 | 80 | 90 |

| Private-multifloor | 50 | 85 | 95 |

| General-one floor | 60 | 90 | 100 |

| General-multifloor | 60 | 95 | 105 |

| HOTEL | 60 | 90 | 100 |

| SCHOOL | 55 | 85 | 95 |

| STORE | 70 | 100 | 110 |

| RESIDENCE | 60 | 90 | 100 |

| SPECIAL USES | |||

| Concert Hall | 40 | ||

| Theater | 50 | ||

| Church | 45 | ||

| Hospital | 50 | ||

| Arena | 70 |

*Noise level in PNdb obtained by converting noise levels from db to PNdb.

**CNR = Composite Noise Rating

Source: Arde, Inc. & Town and City, Inc., A Study of the Optimum Use of Land Exposed to Aircraft Landing and Takeoff Noise, NASA Contractor Report NAS 13697, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Springfield, Virginia: Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information, March 1966), p. 77.

The first column suggests levels of internal noise acceptable under "average" conditions for each activity. The second column indicates the external noise levels which permits an average structure to have an acceptable internal noise level. Finally, column three shows the acceptable external noise level if 10 db of soundproofing is added.

There are, of course, significant limitations to the use of structural soundproofing. Regardless of the type of use, interior ventilation or air conditioning must be provided because windows will need to be kept closed. Further, this approach is ineffective "for uses which involve outdoor as well as indoor activities. This is true of residences whose occupants are likely to be outdoors in good weather."19

4. Airport-Allied Uses Which Have An Incentive To Locate Close to the Airport

There are a number of industrial and commercial activities which are attracted to the vicinity of airports. Such activities as listed in the 1960 Tulsa report include: aircraft & aircraft parts manufacturers; air freight terminals; trucking terminals & other allied uses; aviation schools; aircraft-repair shops; warehouses, aerial survey & other similar companies; aviation research & testing laboratories; airline schools; auto storage areas; parking lots; airport motels and hotels; restaurants; taxi and bus terminals; wholesale distribution centers; gas stations.

In addition to these uses, the airport area can be a desirable location for many other industrial and commercial activities which can take advantage of passenger or air freight service. Special provision for such establishments in the form of industrial or office parks, combined if conditions permit, would be of benefit not only to such businesses but to the entire metropolitan area. Fly-in facilities would be an additional incentive. (Crash damage potential would suggest that worker densities be limited in approach areas; further, structural soundproofing might be required if noise conditions so warrant.)

Public Powers to Implement Airport Plans

"Airport Zoning"

Land-use control through the exercise of zoning is potentially the most effective method for implementing airport plans although its usefulness is somewhat limited in dealing with existing development. Currently, however, the intent of "airport zoning" is primarily to protect the air approaches to the airport from interference with aircraft. It limits heights and such uses as might interfere with visibility and communication.

Regulation of height is necessary to ensure that aircraft have sufficient unobstructed airspace in which to maneuver for landing and takeoff. The FAA through its Federal-Aid Airports Program strongly urges, but does not require, that an airport zoning ordinance be in effect.

Most communities adopting such ordinances have used the format of the Model Airport Zoning Ordinance prepared jointly by the FAA and the National Institute of Municipal Law Officers (NIMLO) in 1944, with a slightly revised edition issued in January 1967. This ordinance establishes a number of imaginary surfaces based on the ends of the runway and on a point at the approximate geographic center of the airport landing area called "the airport reference point," and establishes height limits based on the surfaces. Airport operating characteristics vary the dimensions of the height limit zones as described in "Objects Affecting Navigable Airspace," part 77 of the Federal Aviation Regulations. Briefly, these surfaces are:

- Instrument approach surface: a fan-shaped zone beginning at the end of all runways operating under the Instrument Landing System (ILS) increasing to a width of 16,000 feet at a distance of 50,200 feet beyond each end of the runway. It slopes upward at approximately one foot vertically for each 50 feet horizontally.

- Noninstrument approach surface: a fan-shaped zone applied to all non-instrument runways. Dimensions vary depending on the type of aircraft using the airports.

- Transition surfaces: (a) a surface sloping upward and outward one foot vertically for each seven feet horizontally adjacent to all runways for the entire length of the approach zones, and (b) the zones of variable widths symmetrically located on either side of runways, and (c) surfaces adjacent to the instrument approach zone where it projects through and beyond the limit of the conical surface.

- Horizontal surface: a circular surface 150 feet above the established airport elevation with the airport reference point as its center.

- Conical surface: a surface with a slope of one foot in height for each 20 feet of horizontal distance measured in an inclined plane passing through the airport reference point.

Whenever two zones overlap, the more restrictive limitation prevails. (Figure 2 illustrates these surfaces.)

In addition, the FAA has established the clear zone — that area directly below the approach surface extending to the point at which the approach surface is 50 feet above the elevation of the runway or 50 feet above the terrain at the outer extremity of the clear zone, whichever distance is shorter. At jet airports, it generally is about one-half mile long. It is important that all airports acquire a property interest in the clear zone sufficient to ensure that the land remains free of obstructions. Clear zone acquisition is a requirement at all FAAP airports.

Figure 2

Airport Imaginary Surfaces

Source: "Objects Affecting Navigable Airspace," Federal Aviation Regulations, Part 77 (Washington: Federal Aviation Agency, July 1966), p. 22.

The basic problem with regulating height in the vicinity of airports is one of reasonableness. In general, the courts have stated that the airspace above a certain height is in the public domain and may be used for public passage so long as there is no interference with the reasonable use of the land over which the flights take place.20 But, where the surface defining the navigable airspace extends so close to the ground that reasonable use of the land is precluded, the ordinance may be, and occasionally has been, declared invalid.

Recently, in the case Indiana Toll Road Commission v. Jankovich, 379 U.S. 897, 85 S. Ct. 493, 13 L.Ed.2d 439 (1965), the U. S. Supreme Court refused to review an Indiana Supreme Court decision which declared the airport zoning ordinance in Gary unconstitutional as applied to a height limitation for the Indiana Toll Road. This ordinance was based on the NIMLO-FAA Model Airport Zoning Ordinance.

The implications of the Supreme Court's refusal to grant certiorari are not clear. However, the written opinion by the justices suggests that so long as the controls are reasonable as applied, airport zoning, as well as other zoning regulations, will be upheld. The court's own statement is helpful: "As we read the opinion of the Indiana Supreme Court, it certainly does not portend the wholesale invalidation of all airport zoning laws."

Steps should be taken in the planning stage to prevent the construction of obstructions. Therefore, preparation of the airport zoning ordinance (preferably as overlay zones within the comprehensive zoning ordinance) should be initiated as soon as the runway configuration has been determined. Structures which conflict with the height restrictions should be evaluated individually. Those that are definite hazards to the safe operation of aircraft will need to be purchased and cleared by the airport sponsor or moved, if feasible, so that they do not project into the navigable airspace. The cost of removing or relocating an obstruction, or marking or lighting where removal is not feasible, is eligible for assistance under the Federal-Aid Airports Program.

Comprehensive Zoning

Although comprehensive zoning can be of great value in planning the airport environment, its effectiveness in dealing with the areawide effects of airports is seriously weakened by the fact that the power to zone usually rests with local government (municipal and county). State enabling legislation generally permits both airport and comprehensive zoning to be applied within the jurisdiction of the airport's sponsor. But to date efforts to coordinate such controls with surrounding local governments have not been very successful. Since the FAA contracts only with a single sponsor for FAAP funds, there is no compulsion for the others to take steps to implement airport plans. While it is in the sponsor's interest to control land use, it may not be to the advantage of nearby communities.

Part 77 of the Federal Aviation Regulations requires that notice of construction of a possible obstruction to navigable airspace be given, but the FAA must rely on its power of persuasion to achieve compliance. Fortunately, it has usually been successful. Similarly, the airport owner must make a reasonable attempt to resolve land-use conflicts, but the regulations provide no mechanism for resolving conflicts between airport owners and other local governments.

A number of states give public airport sponsors authority to protect airspace approaches via airport zoning across municipal boundaries. In most instances, however, these powers provide inadequate control over the affected areas because they place virtually no limits on the use of land. As a result, developments such as the following have occurred:

In California, the City of Inglewood recently passed a zoning ordinance to permit high-rise construction in the air approach to Los Angeles International Airport. Millbrae, California, changed its zoning ordinance to permit apartment construction at the end of one runway of the San Francisco International Airport. At Max Westheimer Field in Norman, Oklahoma, the longest runway was rendered largely inoperable because of encroaching residential development.

It is apparent that the greatest problems arise when pressure for development favors residential construction at the fringes of the airport. Zoning which prohibits residences in approach zones and other noise-affected areas would solve much of the nuisance problem. However, because the rationale of dispensing with the victim of nuisance rather than the perpetrator may give rise to some questions, it may be helpful to consider the legal aspects of such exclusion.

The Legality of Comprehensive Airport Zoning. — The reasonableness of any application of the police power, including zoning, is based on its relation to the public health, safety, morals, or general welfare. The courts, therefore, have generally looked with disfavor upon any intent to impose a regulation, resulting in a restriction, hardship, or penalty that does not provide a commensurate benefit to the general public. And, where zoning is confiscatory or substantially interferes with the reasonable use or enjoyment of the land, the courts have generally required that compensation be made.

Another generally accepted principle is that zoning for a particular parcel of land must bear some relation to its potential use. For example, exclusive agricultural zoning is often considered confiscatory unless there is a clearly demonstrated demand for agricultural use.

There have been numerous court decisions relating to the "taking" or "inverse condemnation" of land near airports. The major precedent-setting cases are as follows: United States v. Causby,21 established the principle that excessive airport noise could constitute a taking of property. The Court said that "Flights over private land are not a taking, unless they are so low and so frequent as to be a direct and immediate interference with the enjoyment and use of the land." In Griggs v. Allegheny County, 369 U.S. 84 (1962) the Court decided that the airport owner, rather than the U.S. government or the airlines, is liable for depreciation of property values that results from airport noise.

Finally, in Martin v. Port of Seattle, 391 P.2d 540, (Wash. 1964), cert. den., 379 U.S. 989 (1965), the court decided that recovery under the State of Washington constitution provided for inverse condemnation under which recovery was permitted not only for a "taking" of the property but also for damage to the property. Thus, recovery was permitted to those property owners subject to overflights in take-offs and landings as well as to the property owners who were damaged and whose property was adjacent to the path of flight in landings and take-offs.

Land-use controls around airports have been invalidated by the courts on numerous occasions when they have restricted land in affected areas to uses which do not interfere with airport operations or which are not sensitive to noise and other airport environmental effects and when they have caused a substantial decrease in property values of the zoned lands. When there has been no decrease in property values, the courts have almost invariably upheld the imposition of the controls.

Since in most cases the potential value reduction resulting from added noise in proximity to the airport is more than compensated by its increase in value when zoned for industry or commerce, such zoning appears to be legally secure. In addition, comprehensive zoning of the airport's environs could be made more reasonable by the establishment of areawide land development policies to help create a demand for the uses permitted around airports. In sum, then,

Of all the powers that may be available and appropriate (Federal, State, or local) for meeting the noise problem, comprehensive local zoning pursuant to a State enabling act appears to be one of the most promising. With respect to a public airport already encroached upon, it is of little value. But for the many airports to be built and those not yet surrounded, adequate zoning from the standpoints of both safety and noise will promote the public safety and welfare as well as encourage the development and economic well-being of the community.22

In view of the extensive publicity surrounding airport noise cases, the total amount recovered in damages has been surprisingly low. A 1966 summary of the litigation indicates that a total of $84,084 had been recovered from civil airport operators during the previous 10 years and $690,670 from the U.S. government in cases involving military airports during the same period. At the time of that writing, only 21 cases were still pending. Although many other airports had reported that claims had been filed, the vast majority had been decided in favor of the defendant.23

Building and Housing Codes

When residences cannot be excluded from noise-affected areas around airports, annoyance can be minimized by including acoustical construction standards in building codes. Performance standards could be written into the building code which would reduce interior noise to a specified level; structural soundproofing requirements, therefore, could vary depending on the exterior noise level produced by the airport. Studies have shown that substantial noise reduction can be achieved at a relatively small increase in cost. This approach would be especially useful when applied to areas desirable for residential construction except for their proximity to the airport. Although it appears that such standards are justifiable on the basis of maintaining public health, further investigation of their legality is warranted. (Experience with New York City's new code, with noise reduction standards, may provide a fruitful basis for future evaluation.)

Establishing soundproofing requirements in housing codes may present greater problems because they apply to existing structures. The Arde, Inc. report states that there do not appear to be any insuperable legal or technical obstacles to the imposition of higher standards for noise attenuation in existing structures in noise-affected areas, but that special financial inducements — such as loans, grants, or tax abatement — would probably be necessary to obtain general compliance.

In Great Britain, government authorities are paying one-half the cost of insulating three rooms per dwelling against aircraft noise near the London airport. Similarly, the Los Angeles Board of County Commissioners has given preliminary approval (November 1967) to an experimental program to reduce the effects of airport noise by acoustically treating homes in the vicinity of Los Angeles International Airport. The major problem is the allocation of costs on a rational basis among the property owner, the airport, and the community. Despite the obstacles, further attention to this method is warranted, because it is one of the few that can alleviate the noise problem around existing airports.

Taxing Power

Tax abatement is one means of equitably allocating noise reduction costs. It can be an inducement to present and future property owners to comply with the noise attenuation performance standards of housing and building codes.

Since the owner affected by such code provisions is being directed to improve an existing structure, or to build a new structure, to standards higher than those normal for the rest of the community, it would appear to be proper that the assessed value excludes the "value added" by improvement through more costly construction.

Several communities have reduced taxes in noise-affected areas. While such reductions do not, of course, alleviate the noise problem, they are one method for "compensating" the property owner for noise annoyance and may be less expensive than other methods. Tax reduction and other methods which deal with the symptoms of airport development problems should be considered when the areawide planning approach is unlikely to be successful, e.g., around existing airports.

Also, preferential tax assessment can be used to induce industry and commerce to locate close to the airport.

While the employment of tax abatement for this purpose has, perhaps, only marginal significance in the effort to improve land use relationships adjacent to major airports, the knowledge that tax abatement is currently extended in various ways to effect development is of great importance when complex development problems are faced which require the application of a variety of approaches and techniques.24

Acquisition of Property or of Rights in Property

Where there are limits to the application of police-power controls, alternatives such as acquisition of real property and acquisition of limited rights in property must often be considered to create a pattern of compatible land uses in the airport vicinity.

Acquisition of Real Property. — Real property may be acquired by a public airport sponsor through purchase on the open market or through the power of eminent domain.

When a property owner is willing to sell land at an agreed-upon price, a transfer of property rights may be negotiated in the same manner as a sale between private parties. If an owner is unwilling to sell his property or if agreement cannot be reached on the fair market value, the public airport owner can acquire the land through the exercise of his power of eminent domain. Primarily as a result of the public housing and urban renewal programs, the application of eminent domain has been greatly expanded in recent years. Not only may private property be condemned for a public use (such as a highway, school, park, police station), but it may also be condemned for a public purpose (such as renewal of a neighborhood). In most states, therefore, it would be legally permissible to condemn private property to protect airspace approaches.

Many counties and municipalities have acquired land in the clear and approach zones in order to preserve open space, to restrict intensive development, or to remove existing development. A number of communities have been granted funds under the federal open space program to purchase land for the protection of airport approaches. Eugene, Oregon, has acquired 268 acres for park purposes. Cincinnati has developed a major playfield, recreation area, and golf course on land near the airport. Other airport owners have purchased land in approach or clear zones and leased them for such open land uses as recreation and farming. A 1962 survey showed that almost half of city-operated airports own land used for farming.25 Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport, for example, leases 500 acres of its property to local farmers. The ownership of land in excess of that needed for airport operations has the additional value of permitting airport sponsors to expand facilities as needed without having to purchase or condemn land.

There are numerous cases on record of airports having to purchase existing structures in order to extend the runways to accommodate larger airplanes. For example, Salt Lake City recently purchased land in the approach zones of two major runways in order to prevent possible housing development. Similarly, the Tulsa, Oklahoma, Airport Authority condemned, purchased, and cleared a residential area extending one and one-quarter miles south of the primary north-south runway of Tulsa Municipal Airport. This land is being left open to prevent the intrusion of crash hazard damage potential and noise intensity annoyance on possible residents of this critical approach area."26

Some communities have acquired land in runway approach zones for such other public uses as reservoirs, sewage treatment plants, arboretums, etc. Highways down the center of approach paths, as near Chicago's O'Hare, would also help to reduce exposure to noise. Similar efforts may be feasible at other airports.

Airport owners have also acquired property for industrial development. The 1962 Municipal Year Book survey noted above showed that of the 272 airports reporting, 77 lease land for industrial development with 71 providing buildings for industrial use. Considering the extent of airport development in the last five years, the number is probably much higher now. Additionally, many private airports are building industrial parks.

If owners of property in noise-affected areas seek to limit airport operations to reduce their noise exposure, the airport authorities can use eminent domain to purchase their properties.27 In most cases this noise-affected area is so extensive that the cost of purchase and clearance is prohibitive. Recent experience with the Des Moines Municipal Airport suggests a method for partial resolution of this problem. The purchase of avigation easements (see below) was negotiated wherever possible, but when property owners were unwilling to sell, full fee to the properties was acquired by condemnation and then resold with a noise easement imposed through a deed restriction. The difference between the court-awarded purchase price and the resale price (in effect, the cost of the noise easement) varied from $1,500 to $2,000. Structures which were hazards to navigation or which were on property to be used for airport facilities were purchased and demolished.

It has been suggested that proximity to airport noise be included among the reasons for declaring an area "blighted" and eligible for participation in the federal urban renewal program. This suggestion, however, has received little support, partially because the huge costs of purchasing the extensive area subject to aircraft noise are beyond the means of municipal government. In selected cases, however, such an approach may be warranted.

Acquisition of Limited Rights in Property. — Because of the prohibitive costs of extensive fee purchases, the alternative of less than fee purchase is also used. Purchase of limited property rights may take several forms. If little or no development has occurred, government may purchase or condemn development rights at less than the cost of the full fee. This approach is particularly advantageous when land adjacent to an airport is used as a golf course, nursery, farm, orchard, or other form of open land and it is in the airport's interest to prevent more intensive development. A limited interest of the property could be purchased, by negotiation or condemnation, to restrict the owner from putting the land to more intensive use.

The purchase of development rights is most useful when land development pressures have not yet reached the environs of the airport. Where open land uses are located adjacent to more intensive development, the cost of limited property rights may be very close to the cost of the full fee.

Another form of limited property rights is the easement. When used in airport approach zones, such easements take two forms, flight obstruction easements and avigation easements:

[A] flight obstruction easement . . . [is] a "ceiling." . . . The purpose of the ceiling is to increase the margin of safety for flying by assuring that the glide zone will be free from natural growth or man-made obstructions and the pilot's vision unobscured above a designated altitude. . . . An "avigation easement" may or may not contain provisions dealing with obstructions, but, unlike a clearance easement, in express terms it permits free flights over the land in question. It provides not just for flights in the air as a public highway — in that sense no easement would be necessary; it provides for flights that may be so low and so frequent as to amount to a taking of the property.28

Negotiated purchase of avigation easements with owners of developed property in the airport approach zones may be a useful method of reducing the impact of noise from existing airports. While not eliminating development, it compensates the property owner for the increased noise level and thereby precludes suits for noise damages. Model forms which provide for the execution of avigation and flight obstruction easements have been developed.29

The valuation of such easements often presents problems. The method generally used is to base the value of the easement on the devaluation of the land, at its highest and best use, resulting from exercise of the easement. The Air Force has used this method in connection with its airfield operations. Although purchase of such easements by direct negotiation presents no legal problem, condemnation of property solely to prevent suits for noise damage is questionable as an appropriate exercise of public power. A determination of public purpose must be made by the courts.

Leasing property is another method by which the airport sponsor can acquire a partial interest in land it intends to keep open. Leasing may have value in some cases, but it has the major disadvantage of being impermanent.

Powers Above the Local Level

Because of the areawide effects of, and opportunities afforded by, airports, considerable thought has been given in recent years to the exercise of development powers by governmental or quasi-governmental bodies above the municipal level. Governmental units which have been considered are counties, regional or metropolitan agencies, or states.

Counties. — Although counties are generally empowered to exercise zoning powers, such powers are almost invariably limited to unincorporated areas or incorporated areas lacking their own zoning ordinance. While this permits some control over development, the relative ease of incorporation significantly reduces the impact of county zoning.

A notable exception is Marion County, Indiana, in which the state withdrew planning and zoning powers from all municipalities, including Indianapolis, and vested them in a metropolitan planning commission. The commission, governed by the county council, was charged with the responsibility for areawide comprehensive planning and the preparation of a county zoning ordinance. While this approach may have merit, it cannot be expected that cities will voluntarily give up their zoning powers or that states will enable counties to zone for incorporated areas. However, where new airports are built outside of developed areas, county zoning in conjunction with long-range areawide development policies should be enacted. Review of local zoning ordinances for conformance with the county would be a further step toward implementing development policies.

Metropolitan or Regional Agencies. — An alternative to county zoning might be to vest metropolitan bodies — councils of government, public authorities, or special districts — with zoning authority. Although many airports are owned and operated by special authorities, a number of which are called "metropolitan," they have no power to control land use. Similarly, there is no example of a metropolitan agency, other than those confined to a single county, which exercises zoning power. Thus, adoption of this approach to control development across county boundaries would be a complete departure from prevailing practice. Although there might be some desirable aspects to such control, it is not likely to be widely used in the near future.

A small step in achieving regional coordination of land use is the requirement included in the Demonstration Cities Act that all applications for federal public facility grants of regional importance be transmitted to the official metropolitan agency for review and comment. A strong opinion for or against an airport proposal might carry some weight with the sponsor and may be an important consideration by the federal government in deciding whether to grant funds.

The importance of such reviews, however, should not be overestimated. While reviews of such public facility proposals as a sewer system or acquisition of open space can affect development in the vicinity of an airport, no reviews are required of new zoning ordinances, or of zoning changes, or of major private developments. Thus, a large residential community could be developed near the airport with no regional action necessary.

The Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations suggests an extension of this authority to include review of local comprehensive plans, zoning ordinances, and other land-use and development controls and amendments thereto, as well as major public facility proposals of local and state agencies.30 Permitting review of major private development proposals for consistency with metropolitan plans would be a further step in the direction of achieving compatibility.

States. — States have generally delegated to local governments the power to control land use, although there are examples of direct state involvement in zoning. In Massachusetts, the state constitution provides for the legislature itself to exercise zoning power in certain instances. In Nebraska, a state zoning agency exercises zoning powers under certain special conditions. With specific reference to airport zoning, Illinois is notable. In 1963, the state legislature invested the State Department of Aeronautics with the power to

upon request of the political subdivision or subdivisions owning or operating such airport adopt, administer and enforce ... airport zoning regulations . . . which regulations may divide such area [around airports] into zones, and within such zones specify the land uses permitted and regulate and restrict the height to which structures and trees may be erected or allowed to grow.31

Regulations restricting heights in the vicinity of O'Hare Airport and recommending appropriate land uses were adopted by the Department in February 1965, using a draft prepared by the Chicago Department of City Planning. Municipalities in the vicinity were permitted to accept or reject the land-use recommendations of the regulations. Some states might wish to retain direct control of land use within a specific distance of airports. In either case, the state-airport-zoning approach warrants careful consideration as a means of dealing with the areawide impact of airports. The state may be the only body having both the geographic scope and legal authority to prepare and implement airport area plans.

Conclusion

Airports merit special consideration in the planning process both because of their special needs and because of their pervasive effects on the environment. Planning the airport system also requires a high degree of coordination of the activities of governmental bodies as well as of government with an influential segment of the private economy. Finally, airports merit consideration because technological changes beyond the control of local or even state governments can significantly increase or decrease the scale and nature of their effects.

In sum, then, what is needed is a comprehensive areawide approach to airport and airport-area development in which the emphasis is on locating compatible activities — industry, commerce, open space — in the immediate vicinity, and incompatible ones, residential areas in particular, at a distance. In addition, there is a great deal to be done on the national level including assisting in the development of more efficient engine noise reduction techniques, airport feeder systems, and perhaps specialized land-use controls before airport environmental problems can be resolved and opportunities fully considered. In the meantime, currently available techniques can be used more effectively in improving the relationship of the airport to its environment.

Endnotes

1. Federal Aviation Agency, 1966/1967 National Airport Plan, Fiscal Years 1968/1972 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1967), p. 25.

2. Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, United States Government Organization Manual (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1966), pp. 418–420.

3. Gordon Edwards, "Jumbo Jets and the Emerging Airport City," Planning 1967 (Chicago: American Society of Planning Officials, 1967), p. 244.

4. Howard, Needles, Tammen & Bergendorf, A Jet-Age Blueprint for Roanoke Municipal (Woodrum) Airport (Roanoke, Virginia: Roanoke Valley Regional Planning Commission, December, 1966), p. 187.

5. The President's Airport Commission, The Airport and Its Neighbors (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952).

6. Robert Horonjeff, The Planning and Design of Airports (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1962), p. 146.

7. Leigh Fisher and Associates, Transportation: Air Facilities (Titusville, Florida: East Central Florida Regional Planning Council, 1965), p. 64.

8. Horonjeff, Op. cit., p. 48.

9. Warren H. Deem and John S. Reed, Airport Land Needs (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Arthur D. Little, Inc., 1966), p. 32.

10. Dorn C. McGrath, Jr., "Compatible Land Use," Speech at the ASCE/AOCI Joint Specialty Conference on Airport Terminal Facilities, Houston, Texas, April 14, 1967, pp. 8-9.

11. Ibid., p. 13.

12. Federal Aviation Agency, Planning the Metropolitan Airport System, Advisory Circular AC 150/5070-2, September 17, 1965, p. 2.

13. Federal Aviation Agency, Regional Air Carrier Airport Planning, Advisory Circular AC 150/5090-1, February 2, 1967.

l4. Planning the Metropolitan Airport System, op. cit., p. 4.

15. Pub. L. No. 88-280, 49 U.S.C. Sec. 1110(4) (1964).

16. Tulsa Metropolitan Area Planning Commission, Metropolitan Areas and Their Relationship with Surrounding Land Use: 1975 (Tulsa, Oklahoma: The Commission, 1960), p. 23.

17. State of Wisconsin, Department of Resource Development, State Aeronautics Commission, Wisconsin Development Series, State Airport System Plan: Technical Supplement, Madison, 1966, p. 25.

18. Arde, Inc., and Town and City, Inc., A Study of the Optimum Use of Land Exposed to Aircraft Landing and Take-Off Noise, NASA Contractor Report NAS 1-3697, National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Springfield, Virginia: Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Publications, March 1966), p. 68.

19. Ibid., p. 70.

20. U.S. v. Causby, 328 U.S. 256, 66 S. Ct. 1062 (1946)

21. Op. cit.

22. Robert L. Randall, "Possibilities of Achieving a Quiet Society," Alleviation of Jet Aircraft Noise: A Report of the Jet Aircraft Noise Panel, Office of Science and Technology, Executive Office of the President (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1966), pp. 148–149.

23. Lyman M. Tondel, Jr., "Noise Litigation at Public Airports," Ibid., pp. 123–124.

24. Arde, Inc., op. cit., p. 51.

25. International City Managers' Association, Municipal Year Book, 1962 (Washington: The Association, 1962), p. 365.

26. Tulsa, op. cit., p. 8.

27. However, almost all such suits have been to recover damages rather than to enjoin the use of the airports. In no case has such an injunction been granted.

28. United States v. Brondum, 272 F.2d 642, 644-45 (5th Cir., 1959).

29. Reprinted in NANAC (National Aircraft Noise Abatement Council) Newsletter, May 15, 1964 and August 15, 1963, respectively.

30. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, 1967 State Legislative Program (Washington: ACIR, 1964).

31. Ill. Rev. Stat. 1963, Ch. 15-1/2, Sec. 48.17.

Appendix A

Eligibility Requirements Under the Federal-Aid Airports Program

This appendix summarizes the requirements for receiving aid under the FAAP. Requirements are based on the provisions of the Federal Airport Act, 49 U.S.C. 1101–1120 (1949) as amended, and are spelled out in detail in "Federal Aid to Airports," Part 151 of Chapter 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations. Assistance in interpreting the regulations and in the technical aspects of airport planning and design is available from FAA regional offices.

Sponsor Eligibility

Sponsors must be public agencies, defined in the Act as states, territories, municipalities or other political subdivisions, tax-supported organizations, or a United States agency. The sponsor must also have the financial capacity to pay for its share of the project and be legally able to enter into the agreements required to complete the project.

Project Eligibility

A project must fulfill the following six basic requirements to be eligible for federal aid:

(1) It is included within the scope of the current National Airport Plan.

(2) It is reasonably necessary to provide a needed civil airport facility.

(3) It is reasonably consistent with areawide development plans and will contribute to the accomplishment of the purposes of the FAAP.

(4) Reasonable consideration has been given to the interests of communities in or near which the project will be located.

(5) It provides for the installation of landing aids appropriate to the use which will be made of the airport.

(6) It is one of the following kinds of airport developments:

a. Site preparation including clearing, filling, and grading.

b. Drainage work on or off the airport site.

c. Specified airport buildings such as fire and safety equipment storage. Hangars, automobile parking facilities, and most of the cost of terminals are specifically excluded.

d. Runways, taxiways, and aprons.

e. Fencing, erosion control, seeding, and sodding.

f. Installing, altering, or repairing airport markers and light facilities and equipment.

g. Constructing, altering, or repairing entrance and service roads.

h. Constructing, installing, or connecting utilities.

i. Removing, lowering, relocating, marking, or lighting an airport hazard.

j. Clearing, grading, and filling to allow the installing of landing aids.

k .Relocating structures, roads, and utilities necessary to allow airport development.