Planning the Public Library

PAS Report 241

Historic PAS Report Series

Welcome to the American Planning Association's historical archive of PAS Reports from the 1950s and 1960s, offering glimpses into planning issues of yesteryear.

Use the search above to find current APA content on planning topics and trends of today.

|

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF PLANNING OFFICIALS 1313 EAST 60TH STREET — CHICAGO 37 ILLINOIS |

|

| Information Report No. 241 | December 1968 |

Planning the Public Library

Download original report (pdf)

Prepared by Piero Faraci

Each year, the American public borrows approximately 550 million books from nearly 8,000 public libraries. Yet, according to a national survey conducted by the American Library Association, many public libraries do not meet the association's minimum standards for total number of volumes, number of professional staff, and allocation of funds for operating expenditures. The survey concludes that in order to catch up with stated needs and thus to meet these standards, a total national expenditure of nearly $500 million for books, $38 million for staff, and more than $400 million for operating expenses is needed.2

In addition to an awareness of existing shortages, planning for library facilities requires an evaluation of future needs. These needs will continue to rise at an accelerated pace. The general population growth is perhaps the most obvious influencing factor, but there are others as important. The proportion of younger people in the total population is continually increasing, and is also the largest group of library users, taking between 50 and 60 per cent of the books circulated by the average library.3 Similarly, the rising ratio of retired people with both time and inclination to use library facilities will increase demand for services. Other important factors are the generally higher level of educational achievement and increasing leisure time. Finally, concerted efforts on the part of the librarian to reach a large segment of the public which is now classified among the non-users will have a major influence in determining future public library needs.

Traditionally, planning for libraries was the primary responsibility of professional librarians in cooperation with local boards and library consultants. Recently, however, planning departments have been called upon to contribute to this cooperative effort. A review of 33 general plans prepared for major urban centers since 1960 shows that 22 devoted chapters or sections of chapters to libraries. Recommendations in the general plans ranged from a simple discussion of appropriate sites to a combination of site selection, service areas, programs, and policies.4

The purpose of this report is to assist the planner in recognizing the major trends affecting needs for library facilities and to provide guidelines in the preparation of plans and recommendations for public library developments.

Improving Library Service

The services performed by the modern library extend beyond the simple function of storing books. Leading librarians stress the importance of diversified services and the actual promotion of library facilities for entertainment, information, and self-education. Increased emphasis on service stems from a concern that a large segment of the population does not now avail itself of existing facilities. According to an estimate by Wheeler and Goldhor, 25 to 40 per cent of the total population does not now use library facilities but might do so if encouraged.5 Making the public aware of materials and services available is considered a major responsibility of the modern library. The transformation of libraries from passive and remote institutions to active centers in the community and the ever-increasing use of bookmobiles are evidence of this trend.

Besides books, libraries are providing music and foreign language recordings, films and microfilm, and technical and special interest publications. The library also may show collections of paintings, photographs, and art objects and can provide auditorium facilities for special programs of entertainment, adult education, and community activities.

Greater emphasis on services is also a response to a decline of library use in the inner city. The traditional library has limited relevance to the needs of residents in economically deprived areas, where information and guidance on child-rearing, money management, housing, and the like come much closer to local needs. Here the library can use such tools as lectures, discussion groups, and films. It can also be a source of constructive activities for both young and old by providing such extra services as story hours for children and record concerts for young adults. The efforts by the Cleveland library system to make its branch libraries into community centers is a case in point. Posters are placed in churches, stores, and social agencies and gathering places to make people aware of available facilities. Various community activities are either sponsored by the library or made possible because the facilities are available. These include voter registration drives and discussion groups on such pressing issues as housing. In addition, the branches located in slum areas place strong emphasis on children's programs. Branches are called "treasure houses," with decorations, furniture, and materials oriented toward children. The staff includes librarians with a strong interest in and understanding of childrens' needs.

One of the more obvious ways of bringing service to the public, and to expand library services, is the use of bookmobiles, which are equally useful in high-density areas of the city and in the sparsely populated suburban and rural communities. In 1968, the Chicago Public Library began experiments with the use of bookmobiles for a summer program. The initial objective was to reach young people during summer vacation. The program will eventually operate the year round, with bookmobiles circulating after school hours. Several aspects of this experimental program are worthy of notice. The mobile unit is a brightly painted bus designed to attract immediate attention and to project a feeling of gaiety and fun. A sound system plays popular music.

Other cities experimenting with expanded bookmobile services include Baltimore and New York City. In Baltimore, where the program incorporates many of the features mentioned, one of the librarians contacts the people in the neighborhood to describe facilities and services available and actually knocks on doors to solicit patrons.

In bookmobile services for suburban and rural areas, the objective is to make library facilities available to residents of remote areas, so that distances and economy of operation are the major considerations. In the sparsely populated areas, where no library exists, bookmobiles can bring the much broader resources of a well-stocked central library.

The report Library Facilities, prepared by Herkimer and Oneida counties (New York), outlines the operation of the bookmobile service for areas not served by other facilities, The bookmobiles stop every two or four weeks in 46 different locations of this two-county region. Each unit is stocked with 3,000 volumes, plus films and recordings.6 Circulation for the bookmobile program totals over 80,000 volumes per year.

Even though bookmobiles have the obvious advantages of mobility, flexibility, relatively low cost, attractiveness, and convenience, they do have disadvantages, including the facts that no specialized programs are possible; that materials must be limited; that service is available for each location only for short periods at intervals; and that study and research by patrons are not possible owing to limitations on space and materials.

Standards for bookmobiles are largely determined by local needs and cannot be as comprehensive as those for library buildings. In general, however, the bookmobile service should be planned and operated to provide equal service to children and adults. Its schedule should include afternoon and evening stops for at least 30 hours per week. The appropriate capacity of such units is 3,000 to 4,000 volumes and never less than 2,500 volumes. Bookmobile materials include basic references such as an encyclopedia, world almanacs, Readers' Guide, and information pamphlets.7 Guidelines for bookmobile service suggest an annual circulation of 90,000 volumes, which is comparable in cost to a branch library with about 60,000 circulation.

Although bookmobiles are generally considered an effective and relatively inexpensive means of reaching remote areas, other solutions may be necessary when density of population is too low to justify even this relatively limited expenditure. In Washington State, a rural library system serving a very sparsely populated area gave up the bookmobile and experimented with mailing a catalog of books available in a larger and more centrally located branch library. The catalog is a simple and inexpensive publication similar in format to the Sunday book supplement of a newspaper. Books selected from the catalog are requested by using an enclosed postcard. The experiment is apparently extremely successful. In the first two weeks of the program some 1,700 requests for books were received by the library.

Understanding Library Needs

Planning for library facilities is difficult because of the continuing change in library services. Consultation among the library staff, a qualified consultant, an architect, and the planning staff is essential to determine how existing facilities meet the demand for services, what developments are necessary to overcome shortcomings, and to plan for future needs. The librarian is the pivot of this cooperative effort, and his basic function is to draft proposals based on his evaluation of the community's needs and the capabilities of existing facilities. This includes the responsibility for organizing the library program and suggesting initial planning proposals to make that program possible.

Since most librarians do not have the necessary experience to deal with the details of library planning, a specialized group of librarians well versed in dealing with library problems should provide consulting services. These consultants assist in the selection of sites and advise on building programs as well as on the functional layout of the library. The cost of a library consultant is relatively minimal compared to the total investment, and on the average, equals approximately one per cent of expenditures for new construction.

Another indispensable member of the team is a qualified architect, who, in addition to helping in site determination, must develop appropriate design and preliminary and working drawings as well as cost estimates for construction and supervision. With the increased attention paid to exterior design and interior layouts, architect's fees, which usually range from six to eight per cent of new construction, are a wise investment.8

Planners are not newcomers to this cooperative effort, but their function is too frequently reduced to advising on the selection of sites for new developments. The resources, tools, and knowledge available to the planning staff, however, and the understanding of such factors as pattern of growth, population distribution, land-use regulation, and traffic flows can make this role much more meaningful. In fact, because the planner is in closer touch with the many facets of community needs, perhaps more so than the specialized technician, he can become a positive force in initiating needed improvements.

Evaluation of existing facilities is the first step in determining the need for library improvements. Buildings, whether old or new, should be easily accessible and provide adequate parking. The exteriors should be inviting and the interior layouts so arranged as to stress convenience of use, comfortable surroundings, and ample space. The following tables summarize accepted standards for buildings, book collection, circulation, staff, and space requirements. Although these standards are valuable in the preparation of library plans, local conditions often require modifications. Such problems will be discussed in the "Local Survey" section of this report.

Table 1

Experience Formulas for Library Size and Costs

| Population Size | Book Stock — Volumes per Capita | No. of Seats per 1,000 Population | Circulation — Volumes per Capita | Total Sq. Ft. per Capita | Desirable First Floor Sq. Ft. per Capita | 1961 Fair Estimated Cost per Capita* |

| Under 10,000 | 3 1/2 – 5 | 10 | 10 | .7 – .8 | .5 – .7 | $15 |

| 10,000 – 35,000 | 2 3/4 – 3 | 5 | 9.5 | .6 – .65 | .4 – .45 | $12 |

| 35,000 – 100,000 | 2 1/2 – 2 3/4 | 3 | 9 | .5 – .6 | .25 – .3 | $10 |

| 100,000 – 200,000 | 1 3/4 – 2 | 2 | 8 | .4 – .5 | .15 – .2 | $9 |

| 200,000 – 500,000 | 1 1/4 – 1 1/2 | 1 1/4 | 7 | .35 – .4 | .1 – .125 | $7 |

| 500,000 and up | 1 – 1 1/4 | 1 | 6.5 | .3 | .06 – .08 | $6 |

*Without furnishings (add 15%) or air conditioning (add 10%).

Source: Wheeler and Goldhor, op. cit., p. 554

Table 2

Guidelines For Determining Minimum Space Requirements

Library Location

The location of a library is a major factor in its use. Conflicting considerations, however, can suggest totally different locations. Concern with cost alone, for example, led to the practice of placing libraries where the land for buildings and for parking was inexpensive and readily available. As a result, many libraries are not easily accessible and are under-used. Similarly, misconceptions of what constitutes a proper library site have caused new buildings to be located in civic centers. Although, on the surface, the civic center may appear a logical choice, it is frequently removed from the major flow of traffic and is occupied almost exclusively by office buildings where activities come to an end after working hours. By contrast, evenings and weekends are times of peak activity for a library.9

In general, most library authorities agree that libraries should be centrally located in or near commercial areas and shopping centers in order to promote library use. Studies conducted in 12 large cities support this conclusion. In Atlanta, for example, the Williams Branch in the heart of the commercial area has a circulation of some 100,000 books per year; but the Kirkwood Branch, located in a more traditional site opposite a park and away from the center of activity, circulates only 38,000 books per year. Similarly, the Oak Cliff Branch of the Dallas Public Library located in a prominent shopping area, loaned 163,000 books. The Sangers Branch of the same library system, which is not near pedestrian or shopping traffic, loaned 33,000 books.10

Obviously, the cost of central sites is likely to be high. Whereas the cost of land is estimated to be approximately one-third of construction cost, the cost of the central site may be as high as half the cost of the building. In the long run the added expenditure for a central site is justified by higher circulation and consequently lower cost of operation per unit. In the above example, where circulation was 163,000 volumes, the cost of circulating each book was estimated at 16 cents, while the library with 33,000 annual circulation paid approximately 19 cents for each book circulated.11

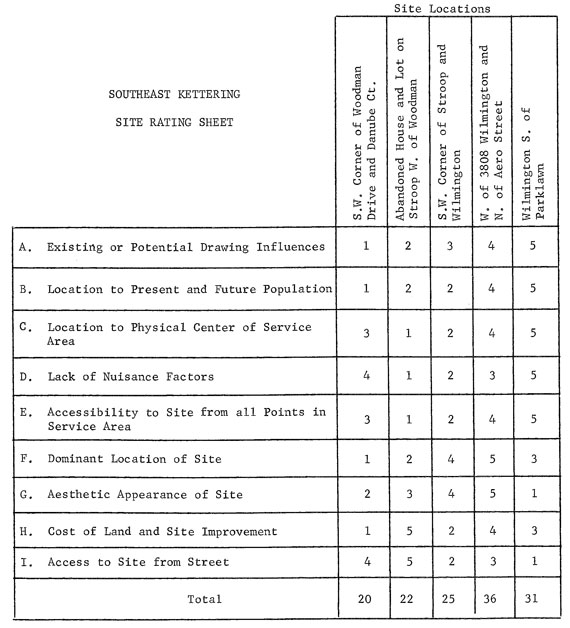

Although central location is considered to be generally desirable, site selection should take into account factors peculiar to local areas. A survey of local behavioral patterns in the use of library facilities should be used in conjunction with the general concept of central location. Although the solution to the problem of site selection is not simple, attempts have been made to provide rational guidelines for this decision. The Dayton, Ohio, planning board, for example, devised a rating system which ranks existing and proposed sites on the basis of nine points summarizing the desirable features of alternative locations. The board's "site rating sheet" is reproduced below.

Figure 1

Planning Recommendations

In evaluation of existing facilities, the entire program should be prepared with the next 20 years in mind. The standards suggested by the American Library Association, based on the experiences of a number of better libraries which have demonstrated the ability to provide necessary services effectively, are valid on the grounds that the performance of good libraries is a fair standard for others to meet. However, as has been noted, library services are expanding and diversifying, and in certain cases libraries are assuming entirely new functions. Costs, too, are constantly rising. The cost of operating a library serving 100,000 people was estimated to be $3 per capita in 1950, but in 1959 an expenditure of $3.44 per capita was needed to provide the same level of service.12 More recent practices would place the per capita expenditure at $4.

Local Survey

A careful evaluation of local characteristics is essential to minimize reliance on general standards and develop, instead, a criterion for library service tailored to local needs. It is important that the planner develop a personal understanding of specific community objectives. Becoming familiar with the community and the neighborhoods, becoming involved in community affairs, meeting with local groups, members of minority groups, public officials, teachers, newspapermen, and, of course, the librarians, is an essential part of the planning function. Combining this with a systematic study of actual conditions is necessary in the preparation of a library plan.

An appropriate beginning for the local survey is an inventory of each existing library in terms of the characteristics of service (service area, circulation, book stock, and hours of operation); exterior physical characteristics (location, surrounding land uses, building condition, size of building, and parking facilities); and interior physical characteristics (total space on the main floor, meeting room space, seats for adults, and seats for children).

The next step is to determine whether each library, as described by the inventory, meets local objectives for service, which are determined by applying national library standards (modified, where appropriate, to meet special local needs). The method used in the preparation of a branch library plan for the Cleveland metropolitan area,13 will be discussed below. An important feature of this report is the extensive use of local data to evaluate conditions and as a basis for recommendations. The data were obtained, in part, through a questionnaire especially prepared for this purpose, which is reproduced in the appendix.

Service Areas

To evaluate existing facilities, it is first necessary to determine the actual area served by each library, the number of people who live within this area, and the services they require. The usual approach in determining the service area is to apply American Library Association standards, which suggest that patrons should be able to reach the library in no more than 15 minutes' travel time, for urban areas, or 30 minutes in rural and suburban areas.14 The extent of services needed is then based on the total number of people who can get to the library within the stated times.

This approach was refined in the Cuyahoga County report, since use of the travel time criterion does not allow for differences in population characteristics. This is important, because the same number of people may make use of libraries in different degrees of intensity depending on such factors as age, education, and income. Intensity of library use by population characteristics was determined by the local survey. The results are shown in Tables 3-6. As an alternative, "service areas" were described by determining the residence of persons who had used the library. This was done through the use of registration data provided by the library and included the total number of people registered and their place of residence. (Where registration was not applicable, the same information was derived from circulation slips.)

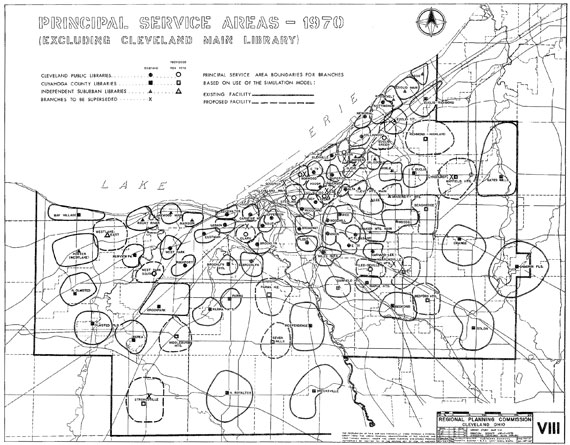

It was determined that 70 to 80 per cent of users lived in a specific concentrated area around each library. The remainder were widely spread in surrounding areas. Service areas were identified as those where most of the users lived, as illustrated by the map.

Table 3

Household Income and the Per Cent of Household Members Who Used or Did Not Use a Library

| Household Income | Per Cent of Users | Per Cent of Non-Users | Total Per Cent |

| $ 0 – 2,999.00 | 31.7 | 68.3 | 100.0 |

| $ 3 – 4,999.00 | 41.7 | 58.3 | 100.0 |

| $ 5 – 6,999.00 | 48.6 | 51.4 | 100.0 |

| $ 7 – 9,999.00 | 60.9 | 39.1 | 100.0 |

| $ 10 – 14,999.00 | 72.2 | 27.8 | 100.0 |

| $ 15,000 + | 77 .6 | 22.4 | 100.0 |

Table 4

Education Level of People Out of School (Education Completed) and the Per Cent Who Used or Did Not Use a Library

| Education Completed | Per Cent of Users | Per Cent of Non-Users | Total Per Cent |

| 0 – 8 grades | 12.1 | 87.9 | 100.0 |

| 9 – 11 grades | 13.1 | 86.9 | 100.0 |

| 12 grades | 26.7 | 73.3 | 100.0 |

| 1 – 3 yrs. college | 46.1 | 53.9 | 100.0 |

| 4 + yrs. college | 63.6 | 36.4 | 100.0 |

Table 5

Education Level of People in School (Education In Progress) and the Per Cent Who Used or Did Not Use a Library

| Education in Progress | Per Cent of Users | Per Cent of Non-Users | Total Per Cent |

| 1 – 6th grade | 88.7 | 11.3 | 100.0 |

| 7 – 9th grade | 96.2 | 3.8 | 100.0 |

| 10 – 12th grade | 97.0 | 3.0 | 100.0 |

| In College | 95.1 | 4.9 | 100.0 |

Table 6

Frequency of Book Reading and the Per Cent of People Who Did or Did Not Use a Library

| Frequency of Book Reading | Per Cent of Users | Per Cent of Non-Users | Total Per Cent |

| Regularly | 81.9 | 18.1 | 100.0 |

| Often | 47.5 | 52.5 | 100.0 |

| Seldom | 29.7 | 70.3 | 100.0 |

| Never | 15.5 | 84.5 | 100.0 |

Figure 2

This system, although somewhat more complex than A.L.A.'s standards, offers an opportunity to determine the average distance that users are willing to travel under different conditions. In addition, when combined with a survey of the registrants who live in the "service area," it also allows measurement of the relationship between specific population characteristics and the extent of library use.

Book Stock

The total number of volumes which should be available to each library is usually expressed in terms of basic book stock per total population, plus a given number of additional books per capita served. But a more accurate indication of actual book needs can be obtained by using registration rather than population figures. As an illustration of the approach, the Cuyahoga County report suggests a minimum of 25,000 volumes for every library with 3,000 registrants, with about six more books per registrant where registration ranges from 3,000 to 6,000 and about four more books per registrant where it ranges from 6,000 to 9,000. This modifies somewhat the standard shown in Table 2.

Location

Location is one aspect of library planning with which the planning agency is most frequently involved. As has been said, generally the library should be centrally located in, or very near, a central business district or shopping center, with modifications to suit local patterns of library use. The Cuyahoga County study bases its recommendations on the results of a local survey, which showed that in most cases library users preferred libraries located close to home. This was true for both adults and children. Second preference was for those libraries located near schools (expressed by children) and near shopping areas (expressed by adults). In low-density or suburban areas the report suggests locating the library near intercepting arterial highways. while in high-density urban areas they should be placed away from heavy traffic, since this acts as a barrier to pedestrian visitors, The second recommendation was to locate libraries near schools and shopping in areas where residents use the library only infrequently, so that this choice of location can stimulate usage.

It is important to notice that location recommendations were based, in addition to expressed preference, on the following factors:

- In most cases both adults and children made a special trip to visit the library and did not combine the library visit with other activities. Although this was true in most cases (49.8 per cent), the second largest pattern of library use was in conjunction with a school by children (17.4 per cent) and in conjunction with shopping by adults (27.0 per cent).

- Most people walked to the library (49.8 per cent); however, a considerable number drove (38 per cent). However, the survey showed that those who walked to the library used facilities more frequently than those who drove. This finding illustrates the importance of locating the library within walking distance and led to the recommendation that facilities should be centrally located to the population served and where access by walking is most convenient.

Contiguous Land Uses

Land uses surrounding the library and the proximity to such traffic generators as shopping centers, civic centers, and schools are additional factors to be evaluated in planning for libraries. The survey for Cuyahoga County included a study of land uses located within 800 to 1,000 feet from each library to determine the predominant characteristics of the surrounding areas. Land uses were classified as follows: (1) civic or institutional, (2) major shopping centers, (3) minor shopping, (4) store grouping, (5) shopping and institutional, (6) single family, (7) multifamily, (8) mixed uses, and (9) school building. The major type of land use surrounding the library was one of the bases for the planning recommendations.

Building Size

An evaluation of building size and condition is necessary to determine whether each structure can provide necessary services. The standards for building size are generally expressed in terms of square feet per capita. The Experience Formulas for Library Size and Costs, suggest minimum sizes ranging from 0.3 sq. ft. per capita for libraries serving 50,000 people or more to 0.6 or 0.65 for those serving 10,000 to 35,000 people, Another method of evaluation is consulting with the librarian. In order to analyze librarians' opinions concerning adequacy of building size, the Cuyahoga County study developed a set of six questions which described adequacy of library space during peak hours. The librarians were asked to give a numerical rating between 1 and 3 for the following situations: (1) lack of table space or sitting space; (2) insufficient browsing space around shelves; (3) congested internal movement; (4) insufficient space around the card catalog; (5) overflow of children into adult areas; (6) high noise level.

A score of 3 was given to indicate that conditions were satisfactory; 2 meant that conditions were adequate; and 1 meant that conditions were inadequate.

Although it was recognized that this evaluation was based exclusively on opinions and that crowding, where it existed, could be caused by poor design as well as by size, this measurement was considered more accurate than population figures and square feet per capita. Local standards for building size were based, not on population, but on a ratio of number of registrants to available space prevailing in those libraries which were considered to be ample in size. The maximum and minimum standard for library gross floor area was established in this case at 1.4 sq. ft. per registrant to 2.6 sq. ft. per registrant.

Another consideration in determining building size for new construction is the minimum area considered necessary to provide adequate services and justify the cost of construction. Wheeler and Goldhor suggest a minimum floor area of 8,000 sq. ft. When projected use of facilities indicates that 8,000 sq. ft. would be too large for actual needs alternative service such as bookmobiles should be considered.15

Total Main Floor Space

With the greater emphasis on interior convenience and comfort, there is also greater emphasis on placing the library areas used by the public for reading and browsing on the first floor at sidewalk level.

Meeting Room Space

Space that is needed for auditorium and conference rooms depends on actual library programs. It should be recognized, however, that with the expanding concept of service, space should be made available for such activities as group meetings, lectures, and film showings.

Parking Facilities

The need for parking facilities should be determined in each individual case. Although the standard usually suggested is one square foot of parking for every square foot of building area, accessibility by walking and car should be taken into consideration.

The information obtained in identifying the "service areas," including the mode of transportation used by library patrons, can be used to determine need for parking facilities. In addition, it is necessary to observe the number of people who park at the library each hour to determine the maximum parking needs. Employee parking must also be provided, and, generally, two parking spaces for every three employees are considered necessary.

Financing

Financial assistance for improvement of library facilities is available through the Library Services and Construction Act (Public Law 89-511 and 90-154) and the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Act (Public Law 89-754).

The Library Services and Construction Act is administered by the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, which provides states with annual grants for the extension and improvement of library facilities. Individual states become eligible by submitting a state plan to the United States Commissioner of Education for approval. Once the grant is authorized, however, the state retains the prerogative of deciding the allocation of federal funds to localities for best use.

A total of approximately $42.5 million plus $9 million carried over from the previous year was appropriated under this act in 1968. The purpose for which the grants can be used and the amount of money allocated in each case is described in the four "titles" of the Library Services and Construction Act. A summary of these titles is as follows:

Title I covers the extension of library services by helping to finance the cost of salaries, books, and materials and equipment. The total sum appropriated for this purpose is $35 million.

Title II provides financial help for actual construction of public libraries in areas where facilities are lacking. The latest appropriation for this purpose was $1,800,000, supplemented by $9 million reserved from the previous year.

Title III is for the purpose of developing local, regional, statewide or interstate cooperative networks between public, school, academic, and special libraries. Approximately $2,281,000 is earmarked for this purpose.

Titles IVa and IVb deal with state-supported institutional libraries and with libraries for the physically handicapped who are not in institutions. Money appropriated for this purpose, however, can be used by public libraries only when they provide special services consistent with the purposes of the title. Total appropriation is approximately $3,400,000.

Federal grants must be matched by local money. The local share for library improvements varies from a minimum of 33 per cent to a maximum of 66 per cent of total cost and can be contributed by the state, the locality, or a combination of both. The actual percentage of the local share is decided on the basis of the state's wealth as determined by the per capita income. Data provided by the Department of Commerce are used for this purpose. The local share for Title III, which covers interlibrary cooperation, however, is always 50 per cent of the total cost. Expenditures for staff and operation can be credited as part of the local share, and these expenditures need not be new but can be part of the normal operating budget.

The application for federal grants is made to the appropriate state library agency by the locality undertaking a program for library service improvement. (A listing of the library extension offices for the 50 states, U.S. territories, and Canadian provinces can be obtained from the American Library Association, Chicago.)

A preliminary proposal describing the planning program to study library needs is first submitted to the state library agency for approval and funding. This proposal, although brief, should contain all the information concerning the scope of the study. The library planning prospectus prepared by the Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission is a good example of such proposals.16 The prospectus should:

- Establish the need for a comprehensive public library facilities and service planning program.

- Specify the major work elements of the planning program. Specifically, it should recommend the desirable scope and dimensions of the library, planning study, as well as exploring data requirements and possible data sources.

- Recommend the most effective method for establishing, organizing, and accomplishing the required studies and suggest possible roles and responsibilities for the various levels of units of government concerned.

- Recommend a practical time sequence and schedule for comprehensive regional library facilities and services planning program as well as an estimate of the staff requirements necessary to complete the work and schedule within budgetary limitations.

- Provide sufficient cost data to permit the development of an initial budget and recommend the funding of the proposed program.

- Determine the extent to which the various levels, units, and agencies of government might participate in the conduct of the library facilities and planning program.

Since funds are available for library planning, the estimated budget for a proposed study is an important part of the prospectus and should be spelled out in some detail. The Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission "Program Cost Estimates" reproduced below is an example of the complete program budget. The detailed schedule of timing for major work elements, which was included in the prospectus, is also shown below.

Table 7

Program Cost Estimates

| A. Study organization and detailed study design | $ 5,000.00 |

| B. Formulation of objectives and standards | 9,000.00 |

| C. Collection of basic data | |

|

|

|

5,000.00* |

|

17,000.00* |

|

6,000.00 |

| Subtotal | 6,000.00 |

|

|

|

5,000.00 |

|

3,000.00 |

| Subtotal | 8,000.00 |

|

|

|

3,000.00 |

|

3,000.00 |

|

3,000.00 |

|

3,000.00 |

| Subtotal | 12,000.00 |

|

|

|

2,000.00 |

|

2,000.00 |

| Subtotal | 4,000.00 |

|

|

|

3,000.00 |

|

3,000.00 |

| Subtotal | 6,000.00 |

|

|

|

2,000.00 |

|

2,000.00 |

| Subtotal | 4,000.00 |

|

2,000.00 |

| D. Planning operations | |

|

|

|

10,000.00* |

| 3,000.00 | |

|

12,000.00* |

| 2,000.00 | |

|

8,000.00* |

| 2,000.00 | |

|

7,000.00* |

| 2,000.00 | |

| Subtotal | 9,000.00 |

|

|

|

6,000.00* |

| 1,000.00 | |

|

6,000.00* |

| 1,000.00 | |

| Subtotal | 2,000.00 |

|

|

|

3,000.00 |

|

2,000.00 |

|

2,000.00 |

| Subtotal | 7,000.00 |

|

|

|

3,000.00 |

|

3,000.00 |

|

3,000.00 |

|

5,000.00 |

| Subtotal | 14,000.00 |

|

8,000.00 |

|

4,000.00 |

|

5,000.00 |

| E. Preparation and publication of reports | 10,000.00 |

| F. General administration and consultant fees | |

|

10,000.00 |

|

2,000.00 |

|

8,000.00 |

|

7,000.00 |

| Estimated total program costs | $ 213,000.00 |

| Estimate of work made available at no cost | 71,000.00 |

| Estimated total net program costs | 142,000.00 |

*Material and data from previous regional planning studies to be made available to the program by the SEWRPC at no cost.

Figure 3

The Timing of Major Work Elements for the Comprehensive Library Planning Program

Additional financial assistance is available from the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Act (Public Law 89-754). The main objectives of this act are to improve educational facilities and programs that would enhance recreational and cultural opportunities and to permit public libraries to be part of this program. The major provisions of this 10-part law, which includes grants to aid public library construction, are as follows:

Title I provides financial and technical assistance to help cities plan and carry out programs for rebuilding and restoring entire sections or neighborhoods of slum and blight, and to improve the general welfare of the residents. Up to 80 per cent of costs can be federally financed in combination with other federal grants-in-aid programs, such as Title II of the Library Services and Construction Act. Appropriations for 1968 were as follows: $12 million for planning, technical assistance, and administration; $200 million for grants and administration; $100 million for urban renewal projects included in city demonstration programs.

Title II provides supplementary federal grants to both state and local bodies for metropolitan development projects, including libraries, as incentives for comprehensive metropolitan planning. No appropriation was authorized for incentive grants for fiscal year 1968.

Title VII amends the Housing Act of 1949 to encourage urban renewal. It authorizes the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development to credit certain local expenditures, including libraries, as a local grant-in-aid if the project was begun within three years of enactment of the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act. The allowance would be 25 per cent of the cost of the facility, or $3.5 million, whichever is less.

Endnotes

1. Joseph Wheeler and Herbert Goldhor, Practical Administration of Public Libraries (New York: Harper and Row, 1962).

2. American Library Association, National Inventory of Library Needs (Chicago: The Association, 1965), Tables 1, 2, 3; pp. 42–44.

3. Herbert J. Gans, People and Plans: Essays on Urban Problems and Solutions (New York: Basic Books, 1968), p. 98.

4. Lois M. Bewley, "The Public Library and the Planning Agency." ALA Bulletin 61: 968–974 (Sept., 1967).

5. Wheeler and Goldhor, op. cit., p. 23.

6. Herkimer-Oneida Counties Comprehensive Planning Program, Library Facilities (Utica, N.Y.: 1966).

7. Wheeler and Goldhor, op. cit., p. 425.

8. American Library Association, Library Facilities: An Introductory Guide to Their Planning and Remodeling (mimeo., n.d.).

9. W. I. Goldman and E. C. Freund (eds.). Principles and Practice of Urban Planning (Washington, D.C.: International City Managers' Association, 1968).

10. Joseph L. Wheeler, Effective Location of Public Library Buildings. Occasional Papers, No. 52, University of Illinois, Library School (Urbana, Ill.: 1958).

11. Wheeler, ibid., p. 13.

12. Wheeler and Goldhor, op. cit., p. 134.

13. Regional Planning Commission (Cuyahoga County), Changing Patterns: A Branch Library Plan for the Cleveland Metropolitan Area (Cleveland, Ohio: 1966).

14. Addenda to Minimum Standards for Public Library Systems, 1966 (Chicago: American Library Association, 1967).

15. Wheeler and Goldhor, op. cit., p. 412.

16. Southeastern Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, Comprehensive Library Planning Program Prospectus (Waukesha, Wis.: 1968).

Copyright, American Society of Planning Officials, 1968.