Planning June 2016

Communities Wanted

A pro bono program helps planners give back.

By Marijoan Bull, Deborah Meihoff, and Robert Paternoster

On a warm summer Thursday afternoon in August 2015, a group of five planners arrived in North Beach, a small community on the west bank of the Chesapeake Bay in southern Maryland.

The town of just 2,000 permanent residents looked a little sleepy. Its eight-block downtown seemed nearly abandoned, with large vacant lots, a few new condo buildings, an office building, and a handful of mom-and-pop shops and boutiques. Its lovely new boardwalk, small but well-kept beach, and refurbished pier were quiet, but poised for the expected onslaught of weekend visitors from the greater Washington, D.C., area.

Community leaders know that North Beach is a special place. And the newly arrived Community Planning Assistance Team would soon find that out. They were there to help the town — recently battered by hurricanes, fires, and the economic recession — usher in a renaissance.

Without a planning staff of its own, North Beach needed the help. So community leaders readily accepted the proposal of their planning commission, supported by the APA Maryland Chapter, to seek pro bono planning assistance through APA's CPAT program. The goal: Create a master plan for the downtown business district.

North Beach, Maryland

Population: 2,011

Project Area: 77 acres

The CPAT Members

Robert Paternoster, FAICP, Team Leader

Philip Franks, AICP, AIA

Wendy Moeller, AICP

Kannan Sankaran

Sidney Wong, PhD

Project Goal: Create a downtown vision plan and conduct an assessment of the town's zoning ordinance

Final Report: www.planning.org/communityassistance/teams/northbeach

About CPAT

The CPAT program offers underserved communities help with focused planning challenges from senior-level planning professionals from around the country. Those volunteer teams have continued to make a difference in communities around the U.S. since the program's relaunch in 2011. And, just recently, the project expanded internationally, with its first project in the Yarborough neighborhood of Belize City, Belize.

The CPAT planners had just three and a half days in North Beach, but team leader Robert Paternoster, FAICP, who is now retired and teaching at Cal Poly University (he is the former planning director for Pittsburgh and two other locales), and APA Programs Manager Ryan Scherzinger had laid the groundwork a month earlier. On that visit, they clarified community goals and expectations, worked out the professional skills needed on the team, and roughed out a work program and schedule. Once on-site, the full team started with more than a day of reconnaissance, then two days of intensive planning work, culminating on Sunday evening with a presentation to the mayor, town council, and the public.

Two stakeholder meetings — a large public gathering held on the first evening and a breakfast meeting with local business owners the following morning — uncovered the community's most important attributes, its greatest problems, and most critical needs. The result was a clear definition of the values of the community:

North Beach is a lovely waterfront community that is family friendly and walkable, and although it is going through a period of revitalization, it will always maintain its small town character and ambiance.

Town leaders sought guidance on rebuilding their depleted downtown, a mere eight-block area divided into two districts — one serving local residents and the other a tourist area along the beach at the foot of the pier. Despite the team's initial inclination to develop both districts, their market analysis quickly revealed little economic support for extensive retail development for locals, who shop in nearby suburban shopping centers.

So the team zeroed in on the two blocks at the foot of the pier. The area contains most of the town's successful shops — small mom-and-pop establishments focusing on local arts and crafts, baked goods and kettle corn, and antiques. Although those businesses struggle in the winter off-season, they help create North Beach's unique local character.

Two large vacant parcels on both sides of Fifth Street provide an opportunity to develop a continuous multistory street wall with storefronts and restaurants along widened sidewalks. The CPAT plan supports a proposal already floated by the owner of one of the vacant parcels: A hotel and conference center, whose economic feasibility would be bolstered by an office building and ground-floor retail. On the other vacant parcel, owned by the city, the plan proposes a performing arts center and an apartment building with active street-level uses, which the team hopes will generate restaurant patrons and pedestrian traffic in the evenings.

The plan also calls for some development surrounding the newly constructed City Hall to create a civic center district, with an existing senior center, a new county branch library, and senior housing. And it recommends short-range actions to improve North Beach's appearance, identity, and community pride, including street tree planting, hand-painted signs for local shops, entry arches over the town's gateways, and festive street pole banners.

The team's presentation of the plan was well received by elected officials and residents, and within a month of their visit, the team delivered a 64-page document. Inside of three months, the town council was asked to fund the tree planting and pole banner programs.

And that's not all. The Economic Development Committee is exploring a gateway arch at a major entrance to downtown, and the zoning ordinance has been amended to incorporate specific changes recommended in the plan. Finally, in response to the North Beach project, the Maryland Chapter of APA formed a committee to assist other communities seeking CPAT assistance.

The report "helped us to coordinate and prioritize important capital projects," said North Beach Mayor Mark Frazer to the team. "Our short- and long-term development agendas are now coming together nicely."

Pat Haddon, cochair of the planning commission, is even more enthusiastic. "The reaction from folks all over town has been fantastic! It has really brought the town even closer together."

North Beach residents, town staff, and elected officials meet with CPAT members following the final presentation of the plan.

South Hartsville, South Carolina

Population: 1,785

South Hartsville Neighborhood Project Area: 544 Acres

The CPAT Members:

Marijoan "MJ" Bull, PhD, AICP, Team Leader

Kimberly Burton, AICP, CTP, LEED AP ND

Karen Campblin, AICP

Alina Gross, PhD

Bridget Wiles

Project Goal: Create a community-based neighborhood revitalization strategy

Final Report: www.planning.org/communityassistance/teams/hartsville

The South Hartsville neighborhood of Hartsville, South Carolina (pop. 7,805), was once a vibrant community, home to black households of various incomes and professions and a place for residents to shop, socialize, and attend church.

But like many neighborhood retail areas, South Hartsville succumbed to a loss of vitality with the rise of an automobile culture and shopping strips full of discount stores. And with the end of segregation, its African American residents had options to shop elsewhere — and they did, furthering South Hartsville's decline. Vacancies increased, building demolitions multiplied, households moving up the ladder moved out (even recently, population was in decline, with a 37 percent population drop between 1990 and 2010), unemployment rose, and disinvestment set in.

Today, South Hartsville is still predominantly African American and has plenty of challenges. But it's also a place with significant assets and positive forces for change. Pockets of well-maintained single-family homes persist, and an active group has renovated the former segregated high school into a community complex with a day care center, after school activities, senior citizen programs, and a community performance space.

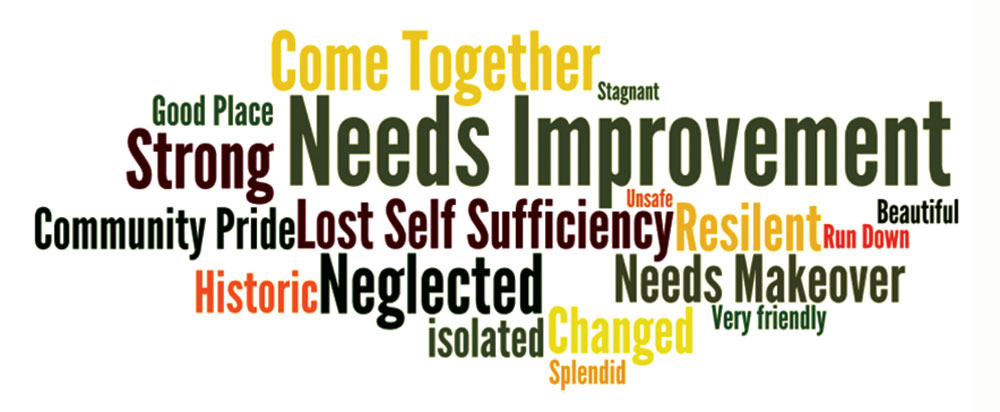

This word cloud is the result of one of South Hartsville's brainstorming sessions. Despite many positive attributes, participants said their town "needs improvement."

The city applied for a CPAT project focused on a neighborhood revitalization strategy for South Hartsville. The target neighborhood has a population of nearly 1,800, with 77 percent of the households being of low and moderate income. South Hartsville is home to 23 percent of the city's total population and nearly half of its African American population.

Following prep work in June 2014 by CPAT leader Marijoan Bull, PhD, AICP, and APA Program Associate Eric Roach, the team of five planners — all women — arrived in September. They spent Monday through Thursday exploring the neighborhood, engaging with residents, meeting with leaders, and brainstorming revitalization actions.

The neighborhood revitalization strategy was developed with direct, substantial community engagement, including a resident-led walk-and-talk tour of the neighborhood, stakeholder focus group meetings, an open meeting framed around "Voice Your View on South Hartsville," and a report-back session where residents responded to a draft neighborhood revitalization strategy.

Mobility Issues: During their walking tour, planners and residents identified areas where physical barriers limited accessibility and mobility for residents of South Hartsville — whether they were on foot, on a bike, or in a car.

The South Hartsville CPAT included a second community visit to present the final 135-page report directly to residents. At a January 2015 event, the team outlined the actions and highlighted how the NRS was designed with data and infographics that could be excerpted for use in funding applications to support neighborhood initiatives.

Putting community members at the helm was a novel approach for the neighborhood. "This represents the first time a plan has focused just on South Hartsville and had input from its residents," noted Alvin Heatley, EdD, chairman of the Butler Heritage Foundation, which spearheaded the reuse of the Butler High School building as a community center. At the final plan presentation, residents and neighborhood leaders immediately responded to a call to serve alongside agency representatives, elected officials, and city staff on an implementation team — a positive indicator of how the NRS was embraced by locals. That team has been meeting once a month since February of 2015, and has since partnered with Habitat for Humanity to renovate neighborhood homes, among other activities.

As with any planning effort, the NRS included short- and long-term action items. A year and a half after its completion, the following actions have taken place:

- The Planning Board adopted the NRS as part of the city's comprehensive plan in October 2015.

- The city installed lighting, new sidewalks, and security cameras in areas identified as needing attention. It is working with Duke Energy to update streetlights on the main corridor.

- Twenty-five residents were trained in and completed (in July 2015) a housing conditions and household income study.

- The city began restoration of the "Colored Cemetery," the final resting place of local African American leaders, which the community sees as central to South Hartsville's identity and heritage.

- The city applied for and received funds to demolish an abandoned apartment complex.

- The city is preparing a contract to complete a housing market study to look at infill development opportunities.

- The city launched a Business-Builder program with low interest loans for local entrepreneurs.

- Two community police officers were dedicated specifically to South Hartsville.

Clearly, implementation has benefited from committed residents and strong cross-sector collaboration. While there is progress, much remains to be done. There is a missing group — adults 20 to 40 years of age — that lacks a critical voice in the process. Funding still needs to be identified. And activities supporting "pride of place" must be expanded.

Brenda Kelley, a senior planner with the Hartsville Planning Department and a member of the Implementation Committee, summed things up. "South Hartsville has pride. We need to work together to strengthen the social and physical networks and get more people connected. We are moving forward."

Spanish Fork, Utah

Population: 38,538

Project Area: 58 Acres

The CPAT Members:

Deborah Meihoff, AICP, Team Leader

Andrew Vesselinovitch, AICP

Sean Daly, AICP

Robert Simons

Robyn Eason, AICP, LEED AP ND BD+C

Project Goal: Create a framework for community reinvestment in Spanish Fork's historic downtown

Final Report: www.planning.org/communityassistance/teams/spanishfork

On the opposite side of the country, another small town needed help creating a realistic and actionable strategy to bring their historic downtown back to the center of civic life.

Located at the southern end of the Wasatch Front in central Utah, Spanish Fork (pop. 38,538) has the familiar structure of many small Western cities: a traditional Main Street that's now a state highway, downtown neighborhoods with early pioneer homes, and storefront architecture representing every decade since the 1880s. As Spanish Fork has expanded at the edges to accommodate its more than 200 percent population growth in the last two decades, its original center is now a place most often seen from behind the wheel.

Private and public investment has been concentrated outside of the historic downtown, leaving the modest, locally owned shops of Main Street struggling to compete with nearby large-format retail centers. But community leaders recognized that a reinvigorated city core was essential to ensure a strong future for Spanish Fork — and to maintain its cultural heritage and identity.

As the population has grown, city staff and services have been pressed to keep the pace. In 2014, Community and Economic Development Director Dave Anderson, AICP, applied to the CPAT program, seeking focused planning expertise and new ways to engage residents.

The CPAT arrived last May, and over the course of five days, the group worked with hundreds of residents, merchants, property owners, local organizations, and city leaders to help shape the community's collective vision and craft recommendations to advance it. And, just as in other locales, the team spent the months leading up to the workshop reviewing planning documents, conducting surveys, discussing comparable downtowns and projects, and interacting with local residents and business people over the phone.

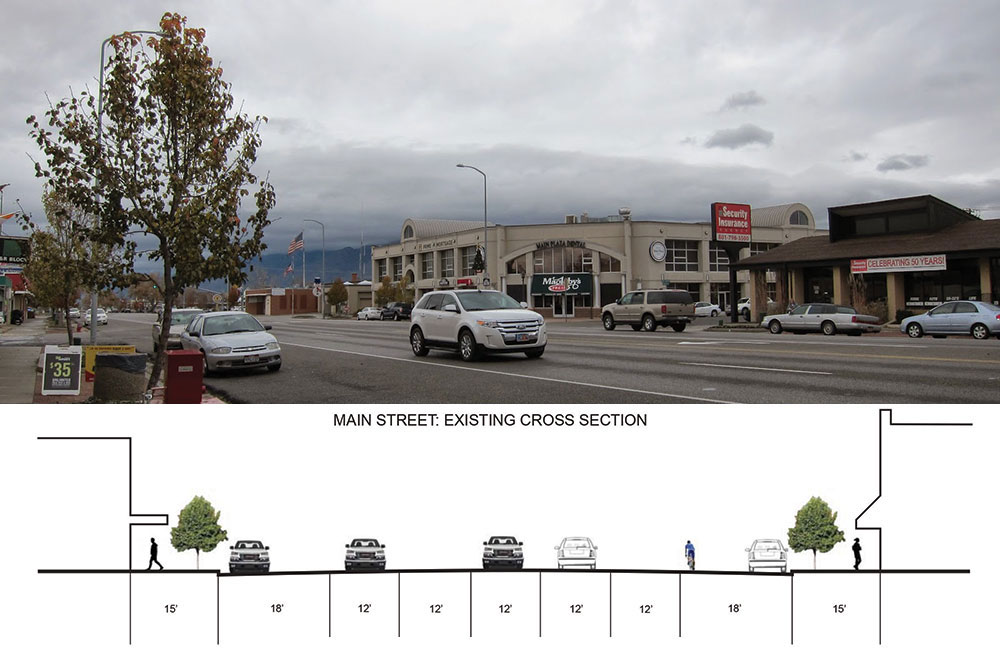

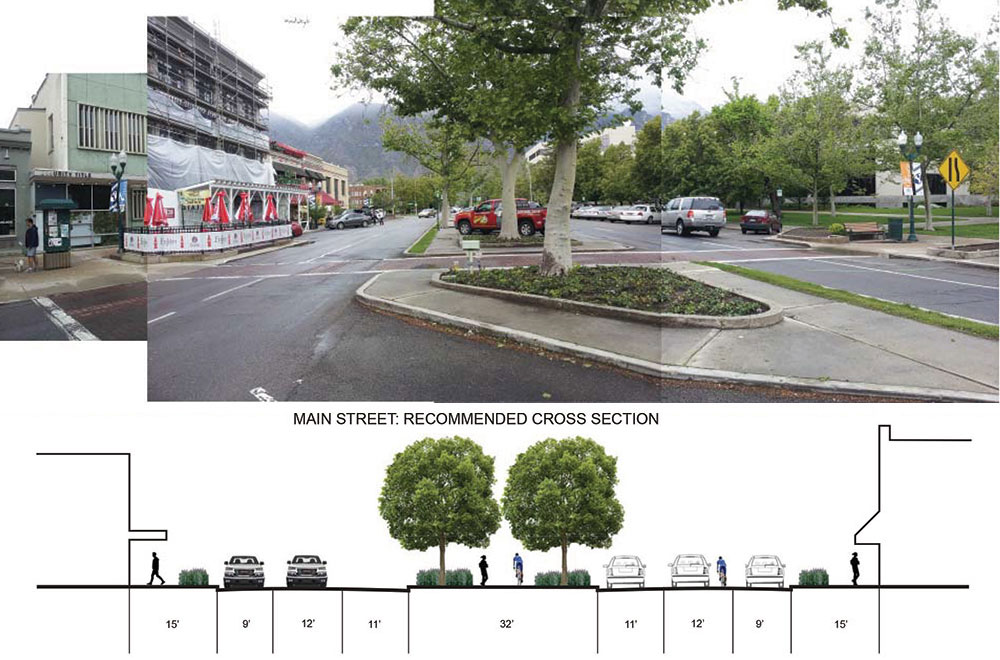

Redesign Main Street right-of-way and pursue funding to construct a street that prioritizes local needs by advancing a safer, business-friendly Spanish Fork Main Street.

Once on-site, the group assessed the economic and physical conditions of downtown, ferreted out best practices that might apply, got the public involved in developing ideas and strategies, and outlined clear steps toward implementation.

Spanish Fork Mayor Steve Leifson kicked off the workshop by hosting a barbecue on Main Street that 500 people attended. There were mapping and drawing activities for children, a photo-essay booth, and comment card raffle tickets.

CPAT members spent the rest of the week talking to people on the street or those that dropped into the open office at City Hall. The engagement focused on attracting diverse participants, including those who had never before interacted with their local government and residents new to Spanish Fork. The team held an economic development workshop with business owners, hosted a design workshop that included members of the Utah Chapter of APA and the American Institute of Architects, worked with Brigham Young University students to administer market and user surveys, met with officials from the Utah Department of Transportation, and held a walking workshop to test potential recommendations before presenting them to the planning commission and city council.

The results? Twelve action-oriented strategies for a reinvigorated downtown. Recommendations included small, immediate steps — such as getting all downtown businesses registered on Google Maps as an inexpensive way to advertise local shops and services — and more ambitious strategies, such as rebuilding the state highway with a center-median linear park, nicknamed the Spanish Fork Heritage Trail, to accommodate safer walking, biking, educational, and recreational options.

Following the on-site workshop, the CPAT planners prepared a step-by-step implementation guide that details the estimated level of effort and the partners that likely will be required for success, as well as immediate steps the community can take. The report was intentionally crafted so that Spanish Fork leaders could take ownership of it, updating and adjusting it as interests and conditions change.

In the end, each of the teams delivered more than just a plan to Spanish Fork, South Hartsville, and North Beach. The volunteer planners helped the local communities unlock their thinking and energy toward achieving their goals. Each community now has the tools — and renewed momentum — to nurture what makes it special and fosters the change that will keep it thriving.

Marijoan Bull teaches urban planning at Westfield State University in Westfield, Massachusetts, and has more than 25 years of professional planning experience. Deborah Meihoff is the principal of Communitas, a consulting firm in Portland, Oregon. She specializes in strategic revitalization and implementation planning. Robert Paternoster is retired, and serves as an adjunct professor at Cal Poly University. He is the former planning director for Pittsburgh and Long Beach and Sunnyvale, California.