Planning April 2017

The Price Is Right

Parking fees aren’t just about making money. They’re also about changing people’s behavior.

By John Dorsett, AICP

Parking is a vital asset for cities.

It plays an essential role in helping to support business development and the success of established businesses. It also has a significant impact on the quality of life of residents. For many communities, it's also a critical source of revenue.

Parking is also an important planning resource and impacts major land-use decisions. With sound policies and practices, parking can help foster pedestrian and driver safety by helping to reduce roadway congestion. And when facilities are coordinated with public transportation, it can also help promote sustainability.

Ultimately, the approach that cities take to pricing can play a decisive role in how effective municipal parking is as a planning tool.

If cities charge too much, commuters, visitors, and residents will avoid public parking resources in favor of other options, like private garages or parking in areas intended for residential parking.

Many cities struggle when it comes to pricing. It should always be strategic, designed to achieve important planning and financial sustainability goals. However, rather than basing parking pricing decisions on their own individual needs and challenges, many cities rely on benchmarking and base their prices on what other cities charge.

The problem with benchmarking is that every municipality is unique. Densely developed urban communities face much different parking challenges than more spread-out cities.

Communities with multiple parking structures have very different expenses than those that primarily administer surface parking. And then there are cities' varying weather and social factors, which also affect parking.

In cases where benchmarking can be effective, cities often do it wrong. Common benchmarking errors include comparisons with cities that have different cost structures and financial needs, inconsistent land-use characteristics, varying goals and objectives, and different traffic levels.

Take Sacramento, California, and Cincinnati, for example. The two cities are roughly the same size, and both are very sophisticated when it comes to managing their parking assets and pricing. Both are focused on supporting business development and being good stewards of their parking resources. However, Sacramento has an additional focus: using their parking assets to help underwrite a significant portion of the cost of building a new arena to house the NBA's Sacramento Kings. To do so, the city monetized its parking system by selling bonds backed by the parking assets.

As in so many aspects of cities, technology is transforming parking. Meters now accept credit cards, and besides the obvious convenience for parkers, it delivers a key benefit to cities: They can charge more for on-street parking. Shelling out $3 or $4 to park is much more palatable when no coins are counted and drivers pay by credit card or with a phone.

Programmable meters also allow parking planners to adjust pricing as needed to achieve the goal of always having one or two vacant spaces per block face during peak hours. It's now possible to institute dynamic pricing — adjusting pricing automatically and in real time as occupancy varies — by combining smart meters with parking guidance sensors.

San Francisco is probably the best-known example of a city that bases on-street parking pricing on demand, changing prices according to location, time of day, and day of the week to assure that parking in lower-demand areas is priced lower than that in higher-demand areas.

Since the program was implemented, San Francisco has met its 80 percent occupancy goal and the practice of circling blocks looking for parking has fallen by 50 percent. Seattle has recently implemented a similar program.

Using Data to Match Price and Demand

The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency's SFpark charges the lowest possible hourly rate to achieve optimum parking availability, defined as having at least one space available on each block most of the time. When and where it is difficult to find a parking space, or where there are too many spaces, rates will increase or decrease incrementally until the right balance is achieved to reach that goal. Left: An SFpark meter outside AT&T Park.

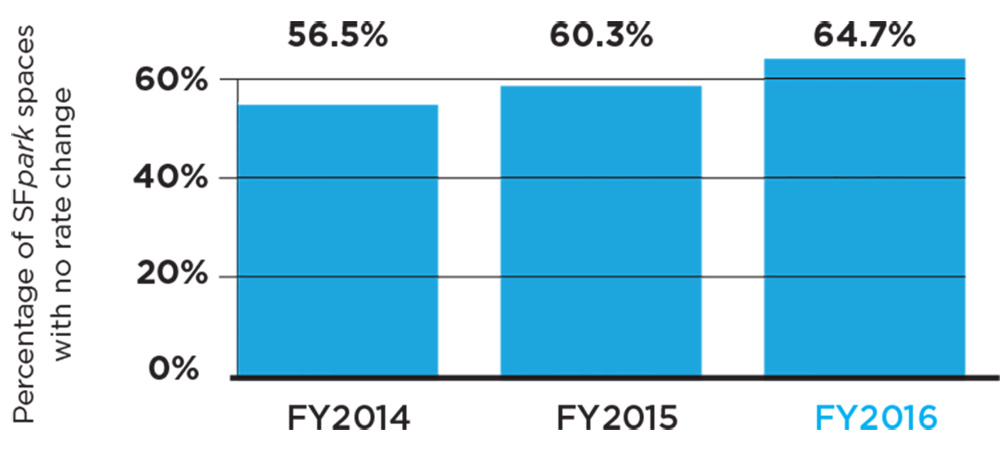

Making Progress: The percentage of SFpark spaces that needed no rate change has risen over three years.

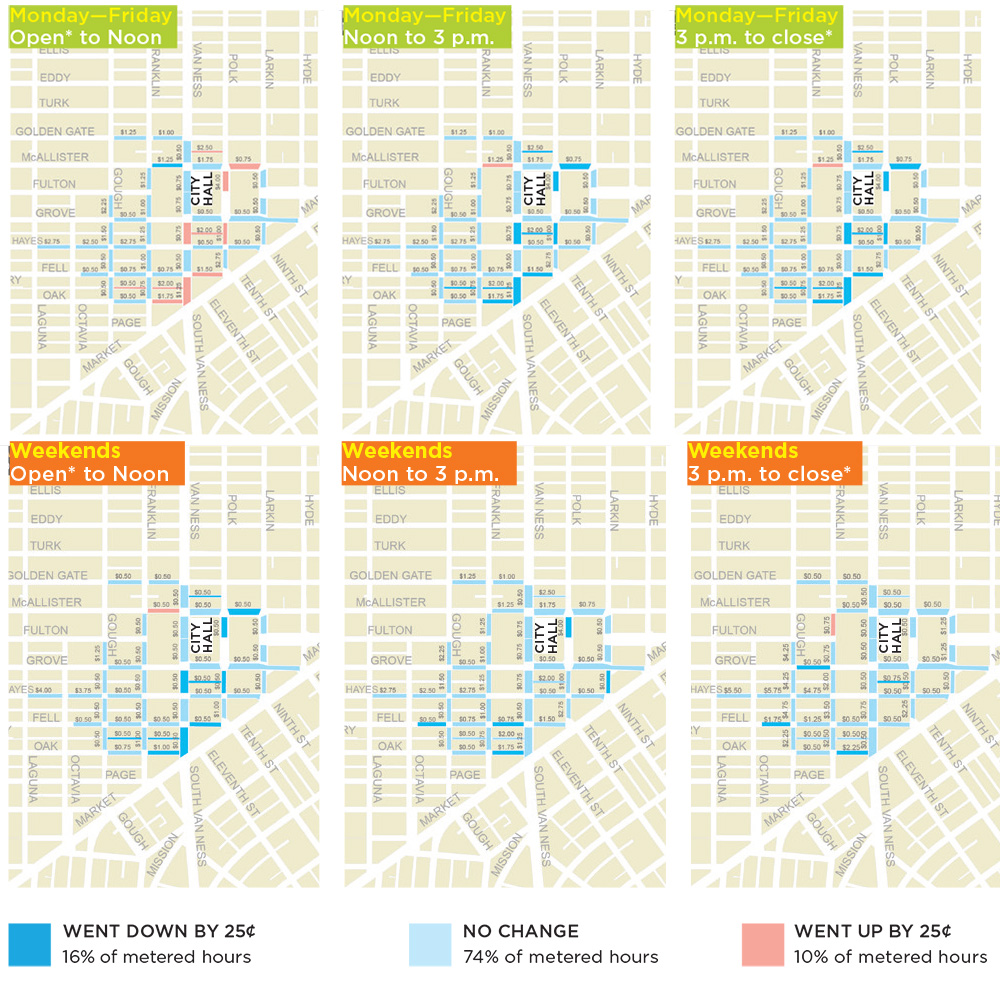

Snapshot: How Prices Changed in One Area

SFpark's 20th demand-responsive rate adjustment for on-street parking meters went into effect February 1. The higher the percentage of "no change" metered hours, the more in balance the rates are with demand. In the Civic Center Pilot Area, meter rates:

*In this pilot area, on-street, noncommercial meters operate Monday through Saturday from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., or 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Sources: Delivering Progress, SFMTA 2016 Annual Report and SFPark January 2017 press release.

Parking fundamentals

Many municipalities try to keep their parking organizations self-supporting. For them, pricing should be built first and foremost to meet those needs — including operations, maintenance, repair, alternative transportation programs, and capital investment. The trick is to price parking high enough to generate those necessary revenues, without driving too many parkers to less expensive competitors or to spots in residential neighborhoods or other areas that might negatively impact the local community. The good news is that, generally speaking, the strategies that promote cities' parking and transportation needs also typically result in increased revenues.

Pittsburgh stands out as a city that does this well. The Pittsburgh Parking Authority has implemented a rate schedule that achieves its primary planning and economic goals while generating the necessary income to service parking-related debt and underwrite the authority's operational costs. The city has also implemented a successful parking tax, which raises revenues for the general fund to help achieve important non parking planning goals.

Parking pricing should be based on supply and demand. By relying on market factors to set pricing, cities can make parking resources more user-friendly, while at the same time increasing revenues and maximizing parking's value as a planning tool.

Municipal parking departments should stop thinking of themselves as parking "owners" and recognize that they are stewards of valuable resources (both the parking and the land on which it rests). Increased revenues will allow a community to fulfill this stewardship role by investing in preventative maintenance (and avoiding deferred maintenance).

The revenues will also allow the parking organization to invest in improved technology to make the customer-service experience better, and in alternative public transportation programs, which can lessen demand and avoid or delay the necessity to invest in additional parking.

Why do planning and pricing go hand in hand? Because pricing is one of the most effective tools at a planner's disposal for influencing parking behavior. Cities can and should charge more for spaces in more desirable, convenient locations and less for those farther away from the central business district and other popular spots.

For this strategy to be effective at influencing parking behavior, the prices must be sufficiently differentiated. Commuters and visitors who value savings will use the lower priced, more distant spaces, while drivers who care more about convenience will be willing to pay a premium. The ultimate goal should be to assure that between 10 and 20 percent of spaces are available in any given parking facility, even at typical peak times.

Many cities, including San Francisco and Cincinnati, have established successful pricing systems in which downtown parking is priced higher than more remote spaces. Seattle has a tiered pricing system with multiple rings of pricing that decreases as one moves farther from downtown.

Of course, commuters and visitors won't use remote lots and structures if they can't get from their vehicles to their jobs and other destinations conveniently. That's why it's incumbent upon parking planners to coordinate with public transportation — and make sure parking revenues absorb that cost. This tends to be more of an issue for mid-sized and smaller cities that may not have a tradition of offering public transportation options.

Many cities, including San Francisco, use parking revenues or parking fees and fines to fund transit and other alternative transportation systems. Another funding strategy used by the Chicago Transit Authority and the Capital Area Transportation Authority in Lansing, Michigan: leasing parking facilities to raise funds.

Communities can derive many benefits from using parking revenues to promote public transportation. Reducing the number of vehicles on roadways supports sustainability efforts, and fewer cars downtown — and circling looking for parking — also means less traffic congestion.

From theory to practice

So how can cities put these pricing and planning approaches into effect? The first step is to conduct an inventory and occupancy study to determine whether there is sufficient parking throughout the community, and whether existing parking is being managed efficiently. Cities are sometimes surprised to find that they aren't actually short on spaces.

Typically, a parking consultant will manually count empty and full spaces over a period of time to determine typical utilization in each parking structure or lot. Parking facilities with sensor-based parking guidance systems, through which every space is monitored by a ground-based or roof-mounted sensor for the primary purpose of connecting parkers with available spaces, can run these counts in real time — and at any time.

Once that data is in hand, parking planners can implement pricing and permit distribution plans that will realign utilization by raising parking rates in heavily used spaces to encourage price-conscious parkers to move to less popular parking locations. One rule of thumb: If a particular parking space or facility is always full or has a waiting list, it's a good indication that the city isn't charging enough.

It can be tempting to think of parking pricing as merely a mechanism for raising revenue. Clearly this is an important consideration, because the money that's earned through parking fees is essential for developing and managing parking and transportation resources.

However, parking is just as important in its role as a planning tool for addressing public perception, growing the economy, influencing parking and commuting behavior, reducing vehicular congestion, and promoting sustainability. To be truly effective, though, each parking pricing plan must address the unique characteristics, challenges, and opportunities presented by that community.

John Dorsett is a certified planner and principal with Walker Parking Consultants.

Driven By Technology

By Bill Smith

Like most other industries, parking is benefiting from a technology revolution — from new software, to mobile tools, to innovative types of hardware.

"The rate of technological advancement is unprecedented," says Dan Kupferman, director of Car Park Management Systems for Walker Parking Consultants.

"Technology has made parking management more efficient, more precise, and easier to operate and audit, which of course leads to greater profitability. Another huge benefit of technology is the ability to make parking more customer friendly than ever before," he adds.

The city of Little Rock, Arkansas, just installed the first EMV certified municipal parking systems in the U.S. Photo by Bill Smith.

Payment Technologies

One area of innovation is the use of EMV chips like those in credit cards, which make it harder for criminals to steal data.

The parking industry has been slow to adopt the standard, though EMV-equipped parking equipment is finally making its way onto city streets.

The city of Little Rock, Arkansas, just installed the first EMV certified municipal parking systems in the U.S., says Renee Smith, president and chief technology officer of Parking BOXX.

"For cities that have yet to make the transition, my recommendation would be to look for equipment with Near Field Communication that can handle both chip and tap payment," she says.

Smith says that tap payment represents the future of parking payment because of the flexibility and security it offers. Tap payment will also provide a competitive advantage by allowing facilities to accept payment via Apple Pay, Google Wallet, and other applications.

Software

Kyle Cashion, principal at IntegraPark, says parking management tools, particularly for fee-collection and accounting, have been slow to change.

"Now sophisticated software platforms can count revenues, transfer them directly to the bank, and instantly provide up-to-date financial data for entire parking systems," he says.

Parking Guidance

The technology, which is already having an impact, will only grow, thanks to connected vehicles and self-driving cars.

Parking guidance technology helps drivers get real-time information about the number of available spaces on each level before they even enter the garage. Photo courtesy INDECT USA.

"Sensors [can] collect data about which spaces are occupied and which are free, and transmit that information to the city's transportation grid," says Dale Fowler, director of INDECT USA, a provider of parking guidance systems. In the not-too distant future, all we'll need to do is punch our destination into our connected vehicle's on-board GPS and our car will find us the best available space.

Inside the garages, sensor-activated green lights show available spots — meaning drivers don't cruise. Photo courtesy INDECT USA.

Autonomous vehicles will take the process a step further, dropping off drivers at the front door of their destinations and then finding a parking space until summoned for the return trip.

"Technology is parking's future," says Kupferman. "The industry's brightest minds are working out solutions to the challenges that have frustrated parking planners for decades."

Using Data to Match Price and Demand

MAKING PROGRESS: The percentage of SFpark spaces that needed no rate change has risen over three years.

The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency's SFpark charges the lowest possible hourly rate to achieve optimum parking availability, defined as having at least one space available on each block most of the time. When and where it is difficult to find a parking space, or where there are too many spaces, rates will increase or decrease incrementally until the right balance is achieved to reach that goal.

An SFpark meter outside AT&T Park.

SNAPSHOT: HOW PRICES CHANGED IN ONE AREA

SFpark's 20th demand-responsive rate adjustment for on-street parking meters went into effect February 1. The higher the percentage of "no change" metered hours, the more in balance the rates are with demand. In the Civic Center Pilot Area, meter rates:

*In this pilot area, on-street, noncommercial meters operate Monday through Saturday from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., or 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. SOURCES: DELIVERING PROGRESS, SFMTA 2016 ANNUAL REPORT AND SFPARK JANUARY 2017 PRESS RELEASE.

Bill Smith is a writer and publicist who specializes in parking.