Planning June 2017

For Better, Not Worse

The relationship between a university and its hometown is like a marriage — making it work takes communication, respect, and even a little love.

By Sandra Beckwith

According to Stephen Gavazzi, a community and university "town-gown" relationship is a lot like an arranged marriage that neither partner can end.

"Unlike businesses, universities can't just pick up and leave the community," says Gavazzi, the dean/director of The Ohio State University at Mansfield and author of The Optimal Town-Gown Marriage: Taking Campus-Community Outreach and Engagement to the Next Level. "Universities and communities can't get a divorce. We're stuck with one another."

Just as in a failing marriage, many of those involved in a town-gown relationship focus on the negatives; the two biggest, he says, are land use and student misbehavior. "What they often fail to see is the extraordinary economic impact of universities on a community," Gavazzi says. "If you look at most of the data from the last recession, you'll see that those municipalities with a higher education institution tended to come out of the recession in better shape than those without one." He cites a 2010 USA Today analysis reporting that anchor institutions such as universities help protect a community during an economic downturn.

To help community planners and university officials assess, understand, and improve their relationships, Gavazzi and colleague Michael Fox, professor of geography and environment at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick, Canada, developed the Optimal College Assessment Tool to measure campus and community member perceptions of one another. This helps take the guesswork out of town-gown relationships, and the tool helps institutions identify and prioritize activities to help improve those relationships.

Before making the tool available to others, they used it in 2014 in Mansfield, Ohio, home of one of The Ohio State's regional campuses, and two of its neighboring towns. The highest rating came from the business community, which benefits from a successful internship program.

A University of Central Florida student reads to students at the Saturday reading camp in Orlando's Parramore neighborhood. UCF's new campus will be built there. Photo courtesy University of Central Florida.

Creating community through collaboration

Successful university-community relationships involve a strong connection between city and university leaders, notes David Lossing, past president of the International Town & Gown Association.

"That extends beyond the mayor and the university president to people at all levels. It's the university's vice president for finance and the city's business manager, the university's architectural planner and the city planning department," he says. "They have to be integrated so that as the university expands its footprint, the city understands the impact."

That's certainly been the case at Oregon State University, which has campuses in Corvallis, Bend, and Newport and operates in 36 counties. The planning process is managed by the school's land-use planning staff, a team of planners and analysts who work with university leaders, public officials, and community members "to make sure the land being developed on campus meets internal stakeholder needs and external stakeholder requirements," says Anita Azarenko, associate vice president for capital planning and facilities services. "We navigate the city's rules and regulations while working to achieve the vision of what we would like the institution to look and feel like in the future."

In 2011, OSU and the city of Corvallis formed an official collaboration to address issues like parking and traffic mitigation, planning, and livability in campus-area neighborhoods. Azarenko cites two projects that have come out of the improved collaboration. To manage traffic created by football game days, which can bring 45,000 people to campus, the university worked with the city, county, and state department of transportation to safely and efficiently move traffic away from Reser Stadium. OSU also collaborated with the city to plan, design, and install a pedestrian crossway at the campus's southern border to solve a public safety issue there.

On the other side of the country, the University of Central Florida seems to be enjoying an extended honeymoon phase while planning their new downtown campus with the city of Orlando and its community college, Valencia College.

"I've been struck by the enthusiasm for the downtown campus," its vice provost, Thad Seymour, says. "People say that they can't wait for the university to open there and ask how they can help. You don't always see this."

Paul Lewis, FAICP, Orlando's chief planning manager, traces that enthusiasm back to the strong relationship between Mayor Buddy Dyer and John Hitt, president of UCF. "Some of this mutual respect developed when UCF built its College of Medicine at our new Medical City near the airport seven or eight years ago," he says, referring to Orlando's medical district.

More recently, UCF became part of the Parramore Comprehensive Neighborhood Plan, the city's vision for a revitalized neighborhood adjacent to downtown. (For more on Parramore's Historical and Cultural Heritage District, see "Preserving Parramore," November 2015.) The East Central Florida Regional Planning Council received $2.4 million from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to plan development around the community's two SunRail commuter stations. UCF's new campus will be built in the Creative Village section of Parramore on the site of the abandoned Amway Arena, former home of the Orlando Magic.

It's a logical location for a large development like a college campus, and in this case, a new K–8 school being built across the street — the first school in the Parramore neighborhood. That development can have a positive impact on the surrounding community, including jobs, more retail, and better security.

"But it can also lead to potential displacement or erosion of special community places or values," says Curtis Ostrodka, AICP, director of community planning at VHB, a firm that does community landuse and master planning and was hired by Orlando to spearhead the Parramore plan. "UCF has been very careful about how it has handled this. It doesn't want to drop the campus out of the sky and become walled off."

As further evidence of that, the university, not the city, convened a group of city leaders and others to discuss how the neighborhood could retain affordable housing if land values continue to climb in coming years. The group is considering creating a community land trust designed to help keep real estate affordable.

Why make this commitment to a transitioning section of downtown Orlando? There are several reasons, says Seymour. One is practicality. The new campus will be home to areas of study with downtown internship opportunities: social work, health care, legal studies, and digital gaming, for example. Another is the opportunity to have a positive impact on the community — and that, Seymour says, is one of the primary drivers.

Investing in neighborhoods

Drexel University, situated on nearly 100 acres across the Schuylkill River from Philadelphia's Center City, has a similar mission: making sure it doesn't function in a silo.

"In 2010, our new president laid out an agenda for the university that called for Drexel to use its academic resources, students, and institutional investment to support the community in deeper ways," says Lucy Kerman, senior vice provost for university and community partnerships.

Since then, Drexel has been involved in a number of initiatives in surrounding neighborhoods, including Mantua, a working-class, predominantly African American community benefiting from an influx of students. The university participated in a project that helped the neighborhood become one of the first in the country to receive a HUD Choice Neighborhoods Initiative Planning Grant for the development of a neighborhood transformation plan. It received the grant in 2010.

"Out of those plans came a loose group that included the Philadelphia Planning Commission. We decided that since some of what our individual entities were planning overlapped, that we should do more planning together," says Kerman.

One result of that improved collaboration is the 2014 designation of the campus and surrounding area as a Promise Zone. That identification, which is part of a federal effort to support neighborhoods that lack resources and suffer from persistent poverty, brings with it support from federal agencies, preference for funding opportunities, and assistance from Americorps VISTA members.

Greensboro, North Carolina, has also benefited from university investment. Home to seven colleges and universities, the city works closely with each to manage issues that range from transportation to the impact of student housing, but one example stands out to Sue Schwartz, FAICP, Greensboro's planning director.

After the city hosted a day-long workshop for the higher education institutions to talk about ways to collaborate on shared facilities, one leader from the University of North Carolina Greensboro "took it to heart," she says. The university had planned to expand into a neighborhood where there was already a great deal of town-gown tension, but the workshop got him thinking about changing those plans to expand instead into a marginal industrial area alongside a neighborhood suffering from a lack of investment.

"UNCG is a state institution, so it could have stayed with its original concept without following our planning or zoning regulations," Schwartz says, noting that as a state entity the school is exempt from local regulations. "Instead, it invested in public engagement with the affected neighborhood, eventually spending a half a billion dollars while preserving a neighborhood plan we had just adopted."

Now known as Gate City Boulevard, the university's expansion includes Spartan Village Student Housing Phase II, a $50.9 million mixed use project featuring two residence halls and 26,000 square feet of retail space. A new recreation center draws students from the main campus to the expansion district.

Drexel undergraduates in a philosophy course work with neighborhood residents at the Dornsife Center for Neighborhood Partnerships. Drexel's Dornsife Center provides "a physical space where students and faculty get to know and work closely with local residents and neighborhood leaders, partnering on initiatives for the long term." Photo courtesy Drexel University.

Transforming transportation

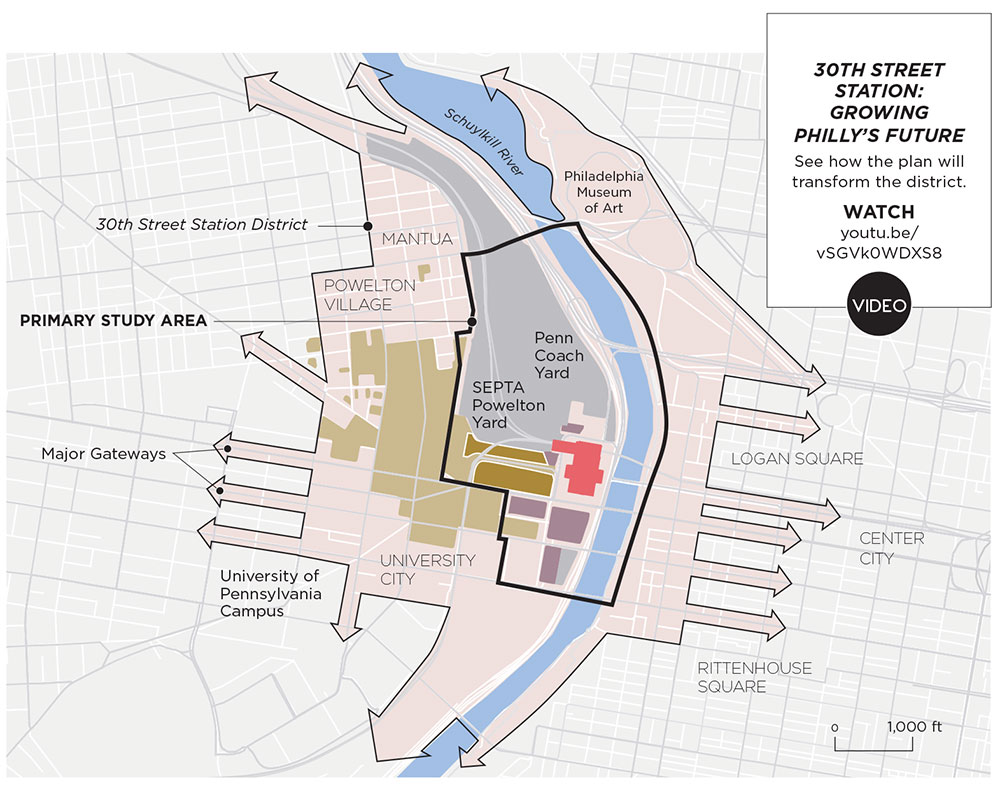

Another Drexel initiative involving the city is designed to help completely reshape the landscape around Philadelphia's public transportation center. The university borders Amtrak's 30th Street Station, the third busiest Amtrak station in the country and a hub for local and regional bus, subway, and trolley routes. The land surrounding the station is underused, but that will soon change as a joint planning group moves to turn the area into a transportation- centered, mixed use district.

The plan for the transformation, the 30th Street Station District Plan, winner of a 2017 Institute Honor Award for Regional and Urban Design from the American Institute of Architects, was a joint master effort led by Amtrak, Drexel, Brandywine Realty Trust, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, and the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority. The city and others on a coordinating committee guided the effort.

Philadelphia 30th Street Station District Plan

In 2014, Amtrak, Brandywine Realty Trust, Drexel University, and state and regional transportation agencies partnered on a comprehensive plan for Philadelphia's 30th Street Station District. Already home to the country's third busiest Amtrak station, the district will have 18 million square feet of new development (including educational and research facilities) and 40 acres of new open space by 2040, integrating the city and station in a transit-centered mixed use neighborhood.

See how the plan, 30th Street Station: Growing Philly's Future, will transform the district: https://youtu.be/vSGVk0WDXS8

Map source: AMTRAK; graphic by David Foster.

"There's plenty of room for Drexel to grow there and capitalize off the transit, pedestrian, and bicycle access," says Martine Decamp, AICP, city planner for the Philadelphia City Planning Commission.

As part of the 30th Street Station plan, Drexel and Brandywine Realty Trust formed a partnership to develop property in Schuylkill Yards, adjacent to the train station, over the next 20 years. Early phases will include five million square feet of mixed use real estate on a 10-acre site next to Drexel's main campus, the station, and Brandywine's Cira Centre high rise. Plans include educational and research facilities, corporate offices, residential, retail, hospitality, and cultural venues and public open spaces.

City planners will monitor Drexel's development to make sure "proposals adhere to the city's comprehensive plan and Amtrak's 30th Street master plan," Decamp says.

She noted that city planners also work closely with the university in neighborhoods bordering the institution to make sure development is in line with the city's density zoning. "The communities do have some real issues," she says. "They're concerned about transportation impact on roadways and parking, extending density into the neighborhoods, and the impact of student housing."

As a result, the city's district plans recommend downzoning in certain areas to protect from unnecessary density, especially on smaller blocks. While there's a high demand for growth, the plans recommend it only where it can be supported, which is often around highly used transit arterials — including the 30th Street Station region.

"We're really committed to being here," Lucy Kerman says of Drexel's efforts in Philadelphia. "When things get rough, we'll deal with that, but we'll still be here the next day and the day after that."

Kerman's philosophy reflects the kind of commitment needed to make a town-gown marriage work.

"The university that puts forth little effort and has a comfortable relationship with the surrounding community is a vanishing species," says Stephen Gavazzi. "Universities and communities can't ignore each other anymore."

Sandra Beckwith is a freelance writer in Fairport, New York.

The Oregon Model

By Chloe Meyere

Nearly 10 years ago, University of Oregon planning professor Marc Schlossberg and architecture professor Nico Larco had a groundbreaking idea: What if a city could harness the creativity of university students and apply it to the problems planners face?

"What if" became reality in 2007 when the pair founded the Sustainable Cities Initiative, the University of Oregon's think tank for sustainable progress.

SCI's annual partnership, the Sustainable City Year Program, connects students with nearby cities in need of pragmatic solutions. Today, the program enlists nearly 400 students — largely future planners — from 30 classes, and has worked in Salem, Gresham, Springfield, Redmond, Medford, and Albany, and with TriMet, Portland's public transit agency.

Jim Huber, AICP, the planning director of Medford, explains how the partnerships work: "Our fire department is going to build two new fire stations. [SCYP] classes came up with a variety of different kinds of designs," he says. "The fire department and firemen could articulate what they needed, and students received valuable education."

That hands-on experience is why KC McFerson, a law and planning graduate student, chose UO. "The opportunity to apply theoretical knowledge to a real-world project helps me as a student by building connections, and helps me as a person who's passionate about creating change in the world," she says.

SCI's success hasn't gone unnoticed. Schlossberg and Larco were consulted by other universities and communities looking to adopt similar programs. Now, the Educational Partnerships for Innovation in Communities Network — also known as "the Oregon Model" — has been implemented by 30 universities across the U.S.

It's gaining international attention, too. In May, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the United Nations sponsored a one-day, 40-country SCI workshop in Bonn, Germany — a reminder that leaders around the world recognize the importance of collaboration in fostering sustainable progress at the local level.

"To create a successful project and garner [support] from a diverse set of team members, it's important to understand everyone's perspective. SCYP was my first foray into understanding and practicing this dynamic," says Jessica Bloomfield, a former SCYP law and planning student and current Washington, D.C., land-use attorney.

"Students think they can change the world, while many professionals are burdened by time constraints, understaffing, budgets, unimaginative policies, etc., and can lose sight of the big picture," she adds. "Let them do it."

Chloe Meyere is the press and communication coordinator for the Sustainable Cities Initiative, and recently received her bachelor of science degree from the University of Oregon.

Case Study: Albion, Michigan

By Lorin Ditzler, AICP

"We have only one rule: you have to keep your porch light on."

In the Harrington neighborhood of Albion, Michigan, prospective residents are getting a hell of a deal. Albion College is renovating dilapidated homes in a neighborhood next to campus and selling them to staff at half price, says college president Mauri Ditzler. The only stipulation is the porch light. It's part of the college's plan to revive this former steel town — a plan that has brought in millions of dollars in development in just a few years.

Patrons wait for a show to begin outside the restored Bohm Theatre in downtown Albion in 2014. Photo courtesy Albion College.

It's a fitting mantra for a town that has been working to keep the lights on for decades, after losing one-third of its population since steel jobs started disappearing in the 1960s. From a high of 12,750 in 1960, Albion's population is now estimated at around 8,300 and dropping. Until the Harrington project, Albion hadn't seen any plans for new home construction in nearly a decade.

A few years ago, as the college faced declining enrollment, its leaders realized that they couldn't grow in a struggling town. They decided to renew their support of the community — to save themselves by helping save the town. But getting started wasn't so easy.

Step one: build trust

The relationship between the blue-collar town and its white-collar college was strained. Perhaps nothing was more symbolic of this than the fact that the college president's home was not in Albion. But in 2014, the college's board of trustees moved the presidential home into town and hired a new president, Ditzler, who would embrace an "open door" policy with the community. The house now sits prominently on the edge of the Harrington neighborhood.

Around the same time, the college announced a promise to the community: It would offer a free college education for up to 10 Albion kids each year who met admission and income requirements. The symbolism of these announcements was huge.

"It was the first clarion signal to the community that something would change," says board chair Don Sheets.

The city's director of planning, John Tracy, agrees. "For years it was perceived that the college was a closed campus. In the last few years, [that perception] has changed tremendously."

Step two: change the story

While the college was mending fences, Albion residents were working on their own changes. The Albion Community Foundation raised $4 million to restore the historic Bohm Theatre, a centerpiece of downtown. This was a massive sum for Albion, and the catalytic project's success changed how people thought about their community.

"If it wasn't for the Bohm getting done, a lot of [recent community improvements] wouldn't have even been thought of," says Samuel Shaheen, a developer and Albion College alum.

"The story the town tells about itself is incredibly important," explains Ditzler, and the Bohm helped people reimagine that story. With a new outlook and champions on both sides, it was time to bring the college and town together to forge ahead.

Step three: work together

In the past two years, Albion has seen a string of successful partnerships between the college and community:

HOTEL. $10 million hotel broke ground last fall. The nonprofit Albion Reinvestment Corporation acquired and stabilized the property, while the college secured funding and a developer (Shaheen, who is developing the project at cost).

COMMERCIAL. Albion College filled five vacant downtown storefronts with classes and administrative offices, while the Albion Reinvestment Corporation secured grants for commercial facade improvements.

HOUSING. The "porch light" project in the Harrington neighborhood has grown to include six square blocks, including properties purchased from the Michigan Land Bank with donations from friends of the college.

JOINT USE. A renovated historic building downtown now holds the Ludington Center, a hub for interaction between college and community members.

RESTAURANTS. As college facilities open downtown, students and staff bring a wave of new patrons. New restaurants are opening and in the works in a town that previously had only half a dozen eateries.

"In the time I've been here, this is the most growth I've seen," says Tracy. He believes the college-town partnership, and the economic confidence it's provided, has been the linchpin. "If it weren't for that, a lot of people investing now would not be investing."

And the Bohm theatre? It's thriving. A live show a few months ago drew a sold-out crowd of 400 people. On a Monday night. In a snowstorm.

Lorin Ditzler is a writer, planner, and musician living in downtown Des Moines. Her passion is finding out what makes small towns tick. College president Mauri Ditzler is her father.