Planning May 2017

Mapping for the Masses

Sustainability planning just got more accessible with a free suite of GIS apps and datasets from Esri.

By Jonathan Lerner

The software developed by Esri, that towering giant of geographic information systems mapping, has become all but essential in planning. It's expensive, though, and complex. Those factors alone have made it challenging for some in the profession to use, and beyond the reach of others who are also concerned with land use, including zoning boards, developers, conservancies, and environmental activists.

In June 2016, Esri launched the Green Infrastructure Initiative, a website that offers free access to an enormous cache of GIS data for the U.S., plus applications with which the information can be assembled, manipulated, and analyzed for a chosen area. It is designed to address green infrastructure not in the narrow sense of the phrase — as a toolkit for handling stormwater — but rather in the original sense of the term: natural landscapes and systems that are sufficiently extensive and intact to provide sustainable habitat for species, or ecosystem services for society, or both.

The Green Infrastructure Initiative's ulterior motive is to promote planning that would safeguard such places. Simply put, that approach starts by identifying natural places that are functioning well — or could be restored to functioning well — and then directs growth and development elsewhere.

"We want to elevate the whole science of geography, and the technology of GIS and its applications, so that normal people can understand it," says Esri founder and president Jack Dangermond. "Private companies, nonprofits — there's thousands of organizations that could use this. It will get them started, and save them thousands of dollars."

Dangermond is passionate about the need to stabilize and preserve what natural places and systems remain in our landscapes. "Green infrastructure ought to be the foundation for our country's evolution in the future. I don't pretend that this [initiative] is the complete answer, but it's one drop in the river of what we need to create, in the way of social understanding."

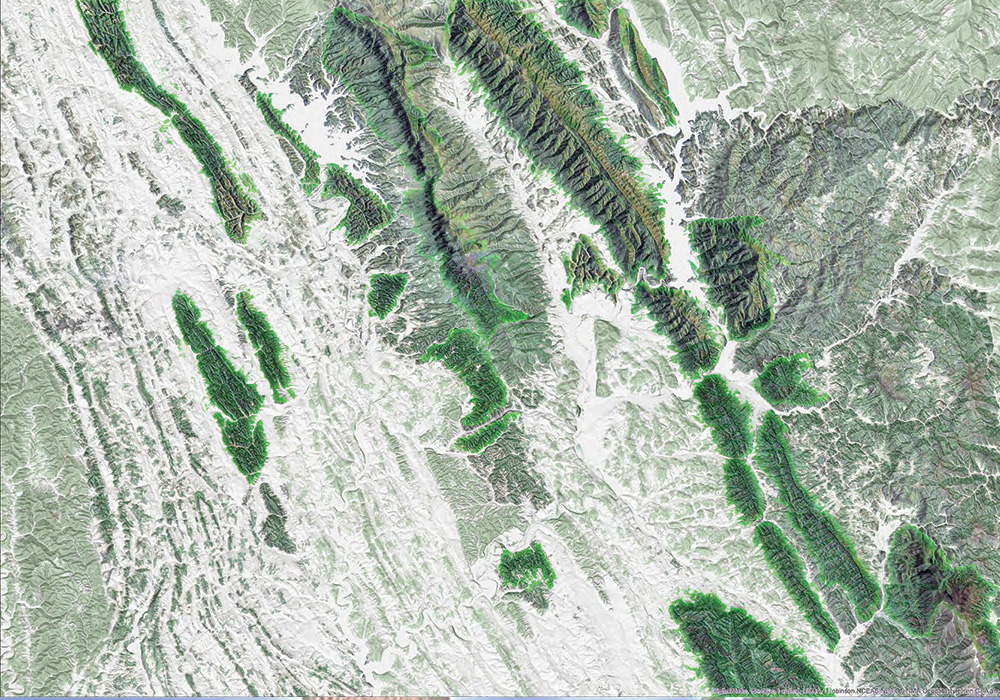

Image courtesy Esri.

Core Connections

Esri's basemap of natural intact habitats is a starting point for sustainability planning at every scale.

1. National

Esri has created a map of natural intact habitats, or cores, larger than 100 acres in size. Data was added to include an assortment of hydrology, species, landform, elevation, soils, and ecosystem information. With more than 570,000 core areas identified across the contiguous U.S., users can view, evaluate, and change the size or focus of the map based on their land management goals.

Source: Esri.

2. REGIONAL

Users can add GIS layers from the Esri Green Infrastructure atlas to identify regional areas of ecological, cultural, visual, and agricultural value, plus hazards like flood zones.

Source: Esri.

3. MUNICIPAL

Governments and agencies can refine the maps by adding local data, which can then be accessed by users in other municipalities to connect landscapes, support native species, protect cultural resources, and promote cooperation among landowners at the local, regional, and national levels.

Source: Esri.

Conceived to reveal and promote the critical value of larger, unspoiled, and unfragmented landscape cores, the Green Infrastructure Initiative website (esri.com/about-esri/greeninfrastructure) is most useful for investigating conditions at larger scales — the county, the watershed, the region.

Its data is drawn from sources such as the National Land Cover Database, which has a rather coarse resolution of 30 meters — meaning that any feature smaller than that is not depicted. Other data comes, for example, from national inventories of wetlands and soils that might be derived from probability- based sampling rather than field observation and thus imprecise, or less than up-to-date. The intact landscape cores identified in the data provided are at least 100 acres in area and 200 meters wide.

"The data probably isn't good enough to do tactical- level stuff within a town," says Hugh Keegan, who manages Esri's Applications Prototype Lab and headed the team that developed the Green Infrastructure Initiative. "But it's good enough to look at strategic patterns."

And those matter. Even tightly focused interventions should be informed by the larger context, if they are to contribute to sustainability. After all, aquifers, wildlife corridors, the impacts of climate change, and other natural systems and conditions do not end at neighborhood or municipal boundaries.

A visualization tool

The Green Infrastructure Initiative website's apps let you focus in on a geographic area to reveal its intact landscape cores. You can then fine-tune the selection and reveal detail by adjusting the relative weight — that is, importance (according to you) — of data layers that show various of the cores' characteristics, such as land cover or soil types, percentage of wetland, or biodiversity and endemic species. The resulting maps can then be downloaded as PDFs that planners could use, for example, to illustrate for decision makers and the public the specific vulnerabilities of locations where development is proposed.

The Living Atlas component of the site includes dozens of maps produced by other organizations that show the range of information that can be incorporated into green infrastructure planning. They illustrate ecological, cultural, or scenic assets, as well as topography and boundaries or environmental hazards. Users can overlay them with many other data layers to view relationships among, for example, soil types, topography, and erosion.

Data from maps in the Living Atlas can also be combined with maps that a user is working up in the Green Infrastructure Initiative's other apps, though just how to do so is rather opaque at present. Keegan says guidance for that will be forthcoming. (Full disclosure: Not all of these Living Atlas maps can be viewed without an Esri software license.) There is also a portal on the site through which users can upload their own data, or recommend data from other organizations, which is intended to continue expanding the number of datasets available.

David Rouse, FAICP, managing director of research and advisory services for the American Planning Association, is the organization's point person in dialogue with Esri. His interlocutor there was Shannon McElvaney, a geographer and self-described "geodesign evangelist," who now works at Critigen in Denver. They have coauthored issues of the Planning Advisory Service's PAS Memo on geodesign, which they define as "thinking that integrates science and values into the planning and design process," thus aligning development plans and design with knowledge of natural systems. Esri's software products now include GeoPlanner, a sophisticated app for collaborative work in this mode.

The Green Infrastructure Initiative, too, can be understood as a tool of geodesign, though a simpler or more preliminary one. For planners with GIS skills and good local data layers, the website may be of limited use, Rouse concedes. "But the idea of it being a national framework is really powerful. We're thinking, at APA, more and more about how things connect across scale, national down to the state, the megaregional, the regional," he says. For planners who have little or no GIS capacity, the Green Infrastructure Initiative tool can help "identify what you need to get more detail on at that local scale."

Rouse also sees its value for places that "may not even have a planner. This is an easy way to generally characterize what's happening in [for example] their county in terms of assets, in rural settings where a lot of this green infrastructure is." He points to the urban-rural divide — an issue he says the presidential election highlighted. "Most of our members are in urban and suburban communities. We see a need to serve rural communities as well, which in a lot of instances have the greatest needs." Regardless of location or technical capacity, planners can use the Green Infrastructure Initiative as a tool for communicating with nonprofessionals, because it can make information about, and visualization of, conditions and alternative proposals accessible and easy to understand.

McElvaney also suggests that it can depoliticize and thus facilitate public dialogue. "You can take the emotion out of things. The map is that conversation piece, that safe place to talk," he says. "You're not saying 'sustainability,' or 'climate change' or 'sea-level rise.' You can go at it from a green infrastructure perspective and talk about protection of people, health aspects, raising quality of life, drought, or flooding." He imagines narratives more like this: "The levees are failing, so what if we restore this natural system and recreate some wetlands here? And by the way, these species will all benefit."

Six Steps to Sustainability

The Green Infrastructure Center (gicinc.org) offers a framework for planners and communities working to conserve natural assets — because sustainability planning is about more than just mapping.

1. Set Goals

What does the community value? Forests? Rivers? Historic battlefields? Identify the green infrastructure in need of protection or restoration.

2. Review Data

Research existing studies. Are they relevant? Is new data needed? Combine local and regional data to connect to the larger national network.

3. Map Assets

Make the ecological, cultural, and economic goals from Step 1 tangible. How do farms, recreational areas, and parks relate to other community spaces?

4. Assess Risks

Which areas are at risk? Are historic landscapes zoned for development? Are forests fragmented by subdivisions? Identify impaired areas that can be improved or restored.

5. Rank Assets and Determine Opportunities

With the community, organize goals by crisis level. What can be saved or restored? Develop strategies to prevent further risks and create future assets.

6. Implement Opportunities

Incorporate new goals into existing city and county planning efforts, or devise new projects, policies, or zoning laws to ensure objectives will be met.

For examples of green infrastructure planning in action, visit gicinc.org/methods.htm.

A work in progress

In developing the platform, Esri brought in Karen Firehock, who cofounded the Green Infrastructure Center, a consultancy supporting local and regional planning organizations, land trusts, and developers; she also teaches graduate planning courses at the University of Virginia.

"They were struggling with how to create this national map: How do you make sure it's scientific and defensible?" Firehock says. The Green Infrastructure Center had already built a computer model to use at smaller scales in inventorying natural assets and connections and identifying opportunities for their protection. Keegan's team was able to adapt and scale up that model.

But the final interface is still more complicated than Firehock had hoped. She says a certain tension developed between her sensitivity to public engagement, which has a prominent place in her consulting approach, and the instincts of the Esri software engineers who "built a lot of cool tools," she says with some amusement, "but they're pretty advanced." She adds, "We cautioned them, 'Don't put all these crazy toggles up there. People don't know what they're doing.' They were app mad."

Keegan concedes that "the apps we published are very dense and presume some insight on how the data were constructed. That we did not communicate well on the website."

Esri is taking steps to remedy that. Contextual guidance explaining how to use the site, including how-to videos and PDF documents, is currently being added to the Green Infrastructure Initiative site. Firehock has also been commissioned by Esri to write a book explaining how to use the information found on the site, "but more importantly, how to add your own data so you can refine the results and make something that's much more precise and applicable to your local needs," she says. "It doesn't know that your community might have done a study and you have all this great information about rare aquatic species in the river. It doesn't read your comp plan. It didn't read your transportation plan. It doesn't know where your growth areas are."

'It really is a first look. It's just a model; it's not a plan. The humans have to make anything that is a plan.'

— Karen Firehock, Executive Director, Green Infrastructure Center

In addition to the website's lack of local detail, some of the national data sets it draws from have weaknesses because, for example, they were compiled over many years, or contain inconsistent terminology, or simply lack information for some locales. Users in some locations may be hampered by the fact that Keegan's team did not include agricultural land.

The site is also weak in cultural data — features like historic districts and heritage landscapes — which are particularly important because they can help people more readily understand their own connections to place, and make the more abstruse scientific information less intimidating.

Enrichment of those categories of information is in the works. Other refinements and additions are also coming. One, McElvaney says, will be a data layer describing "fragments," natural areas and connecting corridors that don't meet the rather arbitrary minimum dimensions of 100 acres in area and 200 meters in width. And the National Land Cover Database, the source of much of the base data on the site, is due for an update this year; when that becomes available, the data drawn from it for the Green Infrastructure Initiative will be recompiled.

All of these additions will make the tool more accurate and useful. Unfortunately, they will not alter the fact that the software is complex, incorporating many variables that users need to be familiar with to use it successfully, and so it isn't easy for people who don't have at least some GIS familiarity.

Locating, acquiring, and matching up multiple categories of data from diverse sources is the biggest time and energy cost in constructing digital maps. David West, leed ap, a principal of the planning consultancy Randall + West who teaches GIS at Cornell, says, "It's wonderful that Esri has done that work, and makes it available in a great format to start working with right away. However, I worry about training students on using this tool if I can't guarantee that it will be available in the future. You never know how a project like this will work. Can I count on Esri supporting this for the next 10 or 20 years?"

Because of the tool's lack of granularity, West doesn't see using it much in his own planning work, which is typically focused on more urbanized places, where large intact cores are not found. But he is excited "to have a web tool that interested community members can dive into, to start the local political conversation about green infrastructure. I think this project will make the idea of green infrastructure planning more prevalent."

Esri's Green Infrastructure Initiative may ultimately be most valuable as a means of educating people about the natural resources and planning issues in their areas rather than for working out the details of specific conservation efforts or development projects.

As Firehock says, "It really is a first look. It's just a model; it's not a plan. The humans have to make anything that is a plan." And those humans, generally speaking, will need to be planners.

Jonathan Lerner, a contributing editor to Landscape Architecture Magazine, writes about architecture, urbanism, and environmental issues.

Resources

Esri offers data and tools for developing green infrastructure strategies: esri.com/about-esri/greeninfrastructure

Naturally Resilient Communities (developed by the Nature Conservancy; APA is a partner): nrcsolutions.org.