Planning June 2018

Planningpalooza

What happens when outdoor music festivals come to town?

By Lindsay Nieman

Around 32 million people attended at least one outdoor music festival in the U.S. in 2014 — nearly double the number of fans at regular season NFL games. In the same year, America's top-five grossing fests — Coachella and Stagecoach in Southern California's Coachella Valley, Lollapalooza in Chicago, Austin City Limits, and San Francisco's Outside Lands — brought in more than $180 million in cumulative ticket sales. And those numbers continue to climb. Add the income generated by corporate sponsorships, merchandising, and concessions, and it's easy to see how the industry has exploded over the last 20 years.

Getting in on the act can be lucrative for cities, too. The San Francisco Recreation and Parks Department made more than $2 million from Outside Lands in 2014. In Chicago, Lollapalooza ticket holders inject around $140 million into the local economy every summer. Austin's South by Southwest invests directly into the local community, partnering with nonprofits to secure health and housing services for local musicians.

Still, residents do not always welcome these events. Congested streets and transit, noise pollution, and damaged public spaces have left many communities wondering if the money is worth the trouble. Hosting outdoor music festivals can be complicated for local communities, but there's a trick to hitting the right notes, and it all hinges on some good planning principles.

A sunset concert in Chicago's Grant Park during Lollapalooza 2017. Photo by Roger Ho/Lollapalooza 2017.

This spring, R&R Studios' Supernova provided shade and a meeting place for Coachella concertgoers by day — and by night, it lit up the sky. Browse the festival's other public art installations at coachella.com/art-directory. Photo by Goldenvoice.

Beyond Woodstock

Destination events are proving to be a powerful economic development tool for cities of all sizes. In Chicago, Lollapalooza attracts 100,000 concertgoers — for $120 to $4,200 per person — to downtown Grant Park every summer for four straight days. Nearly 14 percent of those admissions dollars go to the parks district, according to the city's contract with event organizer C3, along with five percent of sponsorship and five percent of concessions profits.

That revenue has bankrolled thousands of plantings and a multimillion-dollar renovation of Buckingham Fountain. Parks throughout the city also get a share of the profit, and thousands of Chicago kids have attended summer camp on scholarships funded by Lollapalooza earnings. It's also helped make possible new features like Maggie Daley Park, a 20-acre, $60 million addition to Grant Park's east side.

Planner Les Johnson sees an extended version of that in Indio, California, where he's development services director of the city's planning division — and where the country's most famous music festival takes place. The Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival attracts a similar number of people each day as Lollapalooza, but for two weekends instead of one, and it's immediately followed by Stagecoach Country Music Festival, which brings in another 75,000 ticket holders.

The venue there — the Empire Polo Club grounds — is privately owned, but the city still makes about $3.18 million in tax revenue from ticket sales alone, amounting to five percent of Indio's general fund. With the festival now in its 19th year, that money has had an incalculable effect on the region, funding infrastructure projects and improving the year-round quality of life for the whole area, including small businesses. Local eateries dispatch food trucks to festival grounds, and in the surrounding communities, hotel and Airbnb bookings, restaurant reservations, and downtime sightseeing are bookended by preparties and aftershows.

"We see it all as a very important economic driver, for not only the city of Indio, but for the entire Coachella Valley," says Johnson. In total, the nine cities that make up the valley earn about $403 million over those three weekends, a big chunk of which comes from transient occupancy taxes on lodging.

Festival revenue is a boon to areas like Coachella Valley (and nearby Palm Springs) that are already known as vacation destinations. But in 10,000-person host cities like Manchester, Tennessee — which few people likely noticed on a map, let alone visited, before Bonnaroo pitched its first tent in 2002 — outdoor music festivals have kickstarted the tourism industry.

While many of Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival's 80,000 attendees camp on-site at privately owned Great Stage Park, they still manage to spend about $35 a day each in Manchester. And because the grounds are 650 acres of rolling lawns the rest of the year, event staff and volunteers hang around far longer than the festival's four days, installing infrastructure, cleaning up the grounds, and eating and sleeping in the surrounding community. Th at activity translates to more than 30 percent of the entire year's profits for some local businesses, plus $15 million in indirect sales, income, and employment.

"There's a lot of money being spent," Johnson says, "and many, many businesses and most of the municipalities benefit from the revenue generated."

Many of Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival's 80,000 attendees camp at the privately owned Great State Park near Manchester, Tennessee. Event staff and volunteers who stay in the area longer than the four-day festival help to boost the area's coffers. Photo by Andrew Jorgensen.

Facing the music

The benefits music festivals bring, usually delivered with dollar signs, are easy enough to assess. But, apart from repair bills and miles of congested roadways, the negative impacts can be a bit more nebulous, which makes the overall return on investment tricky for some communities to determine.

Chicago's outdoor music festivals have received significant pushback because of damage to parklands, particularly in more residential neighborhoods. After its 2014 showing, Riot Fest was evicted from Humboldt Park, located on the west side of the city, when downpours on the first day alone turned nearly 200 acres into one massive mud pit. Riot Fest covered the $182,000 in damages, but cleanup took longer than expected. Some areas were still fenced off by spring, leaving the neighborhood's largely low- and middle-income Latinx residents without much of their park for seven months — and embodying an equity issue often inherent to destination festivals, which tend to import a majority white and affluent audience.

Lollapalooza has also faced criticism from local groups like Friends of the Parks, who question whether the revenue offsets the lack of public access to a valued downtown greenspace during weeks of setup and repairs.

It's worth noting that some of those impacts can be mitigated before event staff even show up on-site. Across the Harlem River from Manhattan, Randall's Island is 430-plus acres of majority city parkland and amenities. According to David Salerno, concession and events manager, Randall's Island takes care to ensure those amenities remain available for use immediately before, after, and even during the Governor's Ball and Panorama music festivals.

"These are summer weekends; this is when people come out to the park and expect to be able to enjoy it. It's very important for us ... that the event organizers understand that this is a priority for us," Salerno says. That's managed with some nonnegotiable mandates in the contract: Ticket holders can't park on the island. Any pathways near the event space must stay open to the public. And no driving on the grass.

"We're pretty strict about what the events can [and can't] do. We tell them straight up we have an operations plan: no vehicles on the lawn, protect the trees, pitch tents away from roots," Salerno says. "They have to hand-carry or use a handcart — that includes servicing vendors. We have asphalt areas adjacent to where larger builds go [for necessary trucks], so between all that, we keep the space in pretty good condition."

Other cities avoid the problem altogether when private venues take on hosting duties, like Summerfest's Henry Maier Festival Park in Milwaukee. Declared "the world's largest music festival" by Guinness World Records, Summerfest has hosted 11 days of concerts annually on the city's waterfront since the 1970s. The grounds contain permanent outdoor stages, local food vendors, and weather shelters.

That is an important consideration during Midwest summers. Tornado warnings during past Lollapaloozas have forced evacuations of Grant Park, sending attendees scrambling for Starbucks bathrooms and hotel lobbies. Critics of Lollapalooza say Summerfest's economic boost, which comes to a whopping $187 million annually, is even more meaningful to the city, because residents aren't forced to pay for it in park space.

Traffic Control

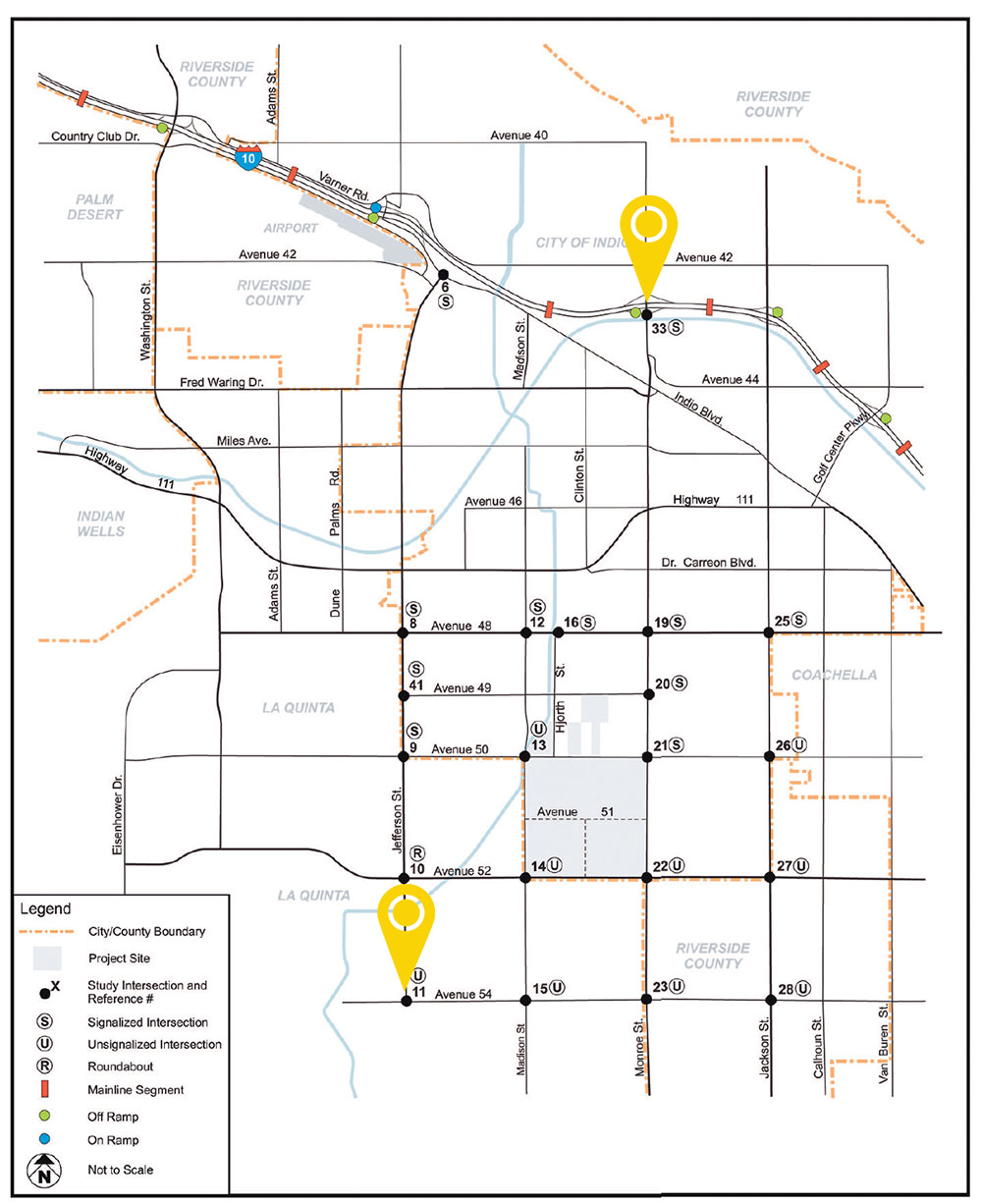

A 2016 addendum to Indio's environmental impact report considers road congestion near Coachella's grounds before, during, and after the festival. From three to four in the afternoon on Friday, when many ticket holders are arriving, only two intersections, flagged in the map below, require mitigation. The four-way stop at the bottom gains temporary signals and traffic control officers to manage the crowds that travel by ride share, official shuttles, and grassroots carpooling, like the "Carpoolchella" bus.

Map courtesy Les Johnson, Ndio Planning. Source: The Mobility Group.

Carpoolchella bus. Image courtesy Coachella.

Setting the stage

Festivals that aren't on public property can still cause plenty of problems, particularly in smaller locales. While larger cities generally have existing public transportation to rely on, rural hosts need to come up with temporary transit solutions from scratch. In Manchester, that means urging locals to stay as far away from the venue as possible, dedicating a lane on Interstate 24 to festival traffic, installing plenty of signage, organizing shuttles, partnering with ride-share companies, and most importantly, staying nimble.

Indio takes a similar approach: Because Coachella doesn't sell day passes, attendees are in it for the long haul, in before the first day and out the last night or the morning after. About a third of the crowd camps on-site, but many ticket holders park daily; others are shuttled in from area hotels or catch ride shares. Maintaining residential road access throughout the event comes down to a traffic plan that is "very, very detailed," but still leaves a little "flex" room, Johnson says.

The Valley's numerous other operating conditions — an environmental impact report; the festival promoter's permit, which sets noise limits, curfews, and maximum event occupancy; security strategies; and waste management contracts — are paramount to pulling these events off with as few sour notes as possible. The bottom line: When the expectations are carefully set and met by all parties, everyone stays happy.

"[Festival promoter] Goldenvoice understands and respects the mitigation measures, as well as the conditions of their permit, and works closely with us to make sure they're in full compliance with all of those — and there's a lot of conditions they have to adhere to," Johnson says. "That's made a world of difference, I think, in the success of having this very large event come into the community and minimizing those impacts."

In Denver, the city streamlined those operating conditions by creating a dedicated department in 2015 that engages with promoters looking to site events on public property.

"We work with them to make sure their event is permitted properly, that they're in compliance, and that they work with all of the required agencies within the city," says Nneka Alston, one of three special events liaisons for the Office of Special Events. "Before our office existed, we found that through misdirection and things of that nature, either organizers were not getting the right information, or if they were, they had to go through many avenues to get the information that they needed."

Since the office was created, Denver has been getting a lot more knocks on their door, Alton says.

"I think the city as a whole is a draw, too," she adds, "but then to know that you can work with a dedicated office that can help get things done, we are seeing a trend in some of those biggest events where we weren't before."

Milwaukee's 11-day Summerfest has a 75-acre permanent home in Henry Maier Festival Park on Lake Michigan. The city doesn't have to consider challenges that other festival cities do, such as damage to other parkland or providing storm shelters. Photo courtesy Summerfest.

Staying in tune (and tuned in)

Denver's first major music festival on city-owned grounds, Grandoozy, is set to take over Overland Park Golf Course in September. It's a big grab for the city, but some residents don't see it that way.

"Denver's never had a festival like [this]," says Alton. "It's a good opportunity, but then we took it a step further and said, but how does the community feel about it?"

Conflicted, it turns out. Residents from the area are worried about the usual impacts — noise, traffic, crime, drugs — and others are reluctant to give up their tee times for a week or two. The Office of Special Events hosted community meetings to gather that info, then brought it to the event promoter, Superfly, so they could put their heads together and minimize those impacts as much as possible.

"We need to make sure we are accountable to [the community]," Alton says. Currently, the department is looking for opportunities to work with private partners like Uber and Lyft to eliminate vehicle congestion, and Superfly has vowed to leave the grounds in better shape than they found them.

Communication and collaboration are vital, Johnson says, because that's what most of the operating conditions are based on. Take noise pollution: On Sundays, Coachella ends by midnight, earlier than weekend shows, because venue neighbors want a full night's rest before work Monday morning. And even though Indio and the surrounding cities have been doing this for nearly two decades, they continue to solicit that kind of feedback on a regular basis.

"It behooves the event organizer to let the community know what's going on because one, that neighborhood is going to embrace it even more," Alton says, "and then two, they probably will attend, and three, you have an advocate for your event should something come up later on."

Johnson has seen that happen firsthand. His department works to make the music festival a good neighbor, and most of the community has embraced it in return — and so have festivalgoers. Coachella tickets completely sold out in three hours this year.

"It's been in so many ways a fabulous experience for us, and the marketing and promotions that have gone into this — it's put Indio on the map," Johnson says. "I mean, I'm watching Black Panther Tuesday night with my wife and one of the final lines was, 'I thought you were taking me to Coachella.'"

He adds, "The festivals are bringing a whole different demographic into the valley, and we hope that has an economic development benefit to us in the long run."

Lindsay Nieman is assistant editor of Planning magazine.

Planning for the Eclipse (Chasers)

By Kristen Pope

Carbondale, Illinois, is using lessons learned during the 2017 total solar eclipse to plan for the next one in 2024. Photo by Alicia Jackson.

Last August, hundreds of communities from coast to coast learned solar eclipses are a bit like a lottery. First, they have to win the lucky draw of being in the path of totality. Then, they hope for a clear day.

Cities and towns that hit the jackpot (a forecast of clear skies) faced an onslaught of visitors coming to witness the total solar eclipse. Carbondale, Illinois, (pop. 26,000) was one eclipse town with a special, and rare, distinction: It will experience another total solar eclipse in April 2024.

The town is using the knowledge it gained during the 2017 event to plan for the next one. "Everything went really smoothly [in 2017]," says Chris Wallace, AICP, the city's development services director. "In hindsight, we probably overplanned a little bit, which worked in our favor."

The biggest challenge the town faced was that they didn't know how many visitors to expect. Eclipse chasers, as visitors are colloquially known, are notorious for booking hotel rooms in multiple locations and choosing last minute where to go based on weather predictions. The town expected anywhere from 2,000 to 100,000 people. Right around 50,000 came.

To avoid too much traffic congestion, visitors were encouraged to park in lots on the edge of town and take special shuttles, which ran every 10 or 15 minutes, downtown. A special Amtrak train also brought visitors into town.

"One of the benefits of the 2024 eclipse is it happens to fall on the same day of the week: Monday," Wallace says, which allows them to estimate the weekend pattern of visitation based on the 2017 eclipse. In 2017, they were surprised that many visitors waited until Sunday or Monday to arrive in town.

However, a spring eclipse brings some different challenges than one in summer. Instead of worries about the heat, organizers will have to prepare for the possibility of severe spring weather. Planners are considering tents and shelters.

They also plan on using different community outreach. "We've learned some of the hype scared some of the local people away," Wallace says. "A lot of the locals [stayed in and] tried to avoid the crowds." In 2024, they will encourage community members to come out and enjoy the festivities more.

"Overall, it was a great learning experience," Fox says. "We've never planned anything on this large of a scale. So I think we have a better idea moving forward, with 2024 just around the corner, of how we want to go about dealing with some of these things."

Kristen Pope is a freelance writer and editor in Jackson, Wyoming.