Planning August/September 2019

Striving for Equity in Post-Disaster Housing

Housing losses in disasters disrupt lives and communities — especially those that were vulnerable to begin with.

By Alexandra Miller, AICP, and Jeffrey Goodman

Disasters often bring out the best in communities: unity, a sense of purpose, a pride in place. On the other hand, as evidenced by past recovery efforts, they can also exacerbate longstanding inequalities. After a disaster's initial impact has passed, wealthy, well-connected residents are able to rebuild their lives, while poorer, more marginalized communities are often left worse off than before.

"We would hope that we could address these [equity] challenges [in our disaster recovery efforts], but over and over we see that they just get worse," says Shannon Van Zandt, AICP, head of the Department of Landscape Architecture & Urban Planning at Texas A&M University. Her research addresses equity issues related to the spatial distribution of housing opportunities for low-income and minority populations.

One University of Pittsburgh study even found that while most black and Latino households suffer losses to their net worth following a disaster, the average white household actually gains wealth. Federal aid contributes to this trend: Studies show that white households and those with more wealth receive more federal disaster funds than people of color and households without resources to fall back on.

If planners want to see their entire communities come back thriving, the time to address questions of post-disaster equity is now, before the damage is done.

But that's easier said than done. Recovery planning experts admit that there is no playbook, particularly around housing. Indeed, of all the aspects of disaster recovery, the reestablishment of appropriate housing in a managed, thoughtful, and equitable way is one of the least-studied aspects of the field.

"We need to collect innovative practices and figure out which ones worked well and which ones didn't," says Van Zandt. "Without a playbook, we're starting over every time."

Houston is one place to look to for best practices, say some experts. The city — hit year after year by severe flooding even before Hurricane Harvey struck in 2017 — is working on programs that seek to create equitable access to housing that will help put them in a better situation during recovery and create better outcomes for all residents in the future.

So, how can planners address housing recovery equity issues before and after a disaster? The first step is to gain a better understanding of the recovery process and how its timeline and design can contribute to inequitable outcomes in the first place.

The federally subsidized Arbor Court Apartments complex in Houston flooded in 2016 and was damaged during Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Both events left some families displaced and others complaining of serious problems, like mold. Tenant Daija Jackson would like to leave, but the Greenspoint neighborhood is one of the few areas of the city that has affordable multifamily units. Photo by William Chambers/The New York Times.

Days late, dollars short

After a disaster, residents' needs are immediate and pressing. However, federal recovery funds can be slow to arrive and loaded with pitfalls. Initial funds available from the Federal Emergency Management Agency or Small Business Administration loans may only be a few thousand dollars — enough to stabilize a living situation but not enough to rebuild a life.

As FEMA states bluntly, federal dollars "cannot make you whole," but are simply designed to "help you move forward in your recovery."

Residents who need assistance over and above these initial, smaller programs must often wait years. Congress appropriates additional recovery dollars on a reactive basis, and in recent years these appropriations have become progressively slower. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Congress appropriated billions of dollars for recovery in 10 days; after Hurricane Michael in 2018, the disaster appropriations bill took seven months.

These delays tend to penalize those who need to take early compensation to just keep their lives going. After flooding in Baton Rouge in 2016, many home owners needing immediate money sought SBA loans. They didn't know that those applications would prevent them from tapping future recovery funds. The convoluted rules around "duplication of benefits" kept $1.3 billion in appropriated housing recovery dollars away from thousands of home owners.

Further complicating the matter, recovery funds — even when available — can be difficult to access for those who need them most. Renters, for example, on average have lower incomes than home owners and often are far more destabilized by the effects of disasters. Yet, for a variety of reasons, both political and practical, federal housing funds favor home owners over renters. Few communities offer aid to recover rental properties after a disaster.

With no control over when their homes will be rebuilt, many renters end up living in hotels or in apartments far from their communities and their jobs, which unduly burdens them and often renders communities unable to replicate their pre-disaster housing mix.

In May, seven months after Michael, Panama City Community Development data showed just two apartments available for lease in all of Bay County, Florida, with waitlists of up to six months. Rents have tripled as unrepaired damage has kept more than half of the pre-storm apartments "unlivable." With workers commuting in from as far away as Tallahassee — 100-plus miles away — local officials told the Panama City News Herald, "The housing crunch is a continued concern for economic recovery since businesses needing workers have few places for them to live."

Slow and inequitable funding shuts down economies and strangles job opportunities, making it difficult for people to cover basic expenses, let alone recover.

The post-Katrina Road Home Program that operated in New Orleans and the rest of Louisiana shows how failure to consider inequalities can taint housing recovery for low-income home owners as well.

In an effort to expedite disbursement, Louisiana state officials made a decision to allocate funds for home repair based on pre-storm housing values rather than need or income. Thus, homes in wealthier neighborhoods, where housing values were higher, received proportionately more money than homes in neighborhoods with lower housing values, despite comparable home sizes and damage levels.

In a city still deeply divided by race and class, the use of pre-storm home value served to amplify inequalities dating back to Jim Crow and the redlining of New Orleans neighborhoods. Under this flawed formula, grant awards in predominantly African American neighborhoods were often comically insufficient for recovery: One home owner received only $1,400 for $150,000 in damage. It took a 2011 class action settlement against the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development led by the NAACP, the National Fair Housing Alliance, and the Greater New Orleans Fair Housing Action Center to reopen funding for 20,000 eligible home owners. By that point — six years after the storm — many had simply chosen not to rebuild.

Generational home owners who have passed their houses down through their families can also struggle to access recovery aid because they may not have deeds and titles required for the application process. After Hurricane Maria, more than 533,000 Puerto Ricans were denied federal assistance on this premise. (For more on recovery in Puerto Rico, see "Puerto Rico Lurches Toward Recovery.")

Supported by federal recovery funds, Houston's Community Land Trust serves as a developer for homes on land bank property. The program helps flooded low-income residents buy affordable homes in less flood-prone areas. Photo courtesy houstonclt.org.

Next to federal aid, private insurance is often the most reliable source of funding for rebuilding immediately after a disaster. But residents who are not required to have insurance often don't, especially lower-income renters and home owners who may not be able to afford additional coverage or who may believe they live in a low-risk area.

It does not help that existing risk assessments and insurance requirements are often outdated. Three-quarters of the homes flooded during Hurricane Harvey were outside the official "500-year floodplain" or within the area that has a 0.2 percent chance of flooding in any given year. Many of the same areas flooded twice within the three years before Harvey as well.

It's apparent that several predictable factors can make it harder for some households and communities to recover, and many revolve around equity and access to resources — or lack thereof. Planners who understand the core equity issues in their housing markets before a disaster hits are uniquely positioned to help design better recovery programs.

According to some, Houston is leading the way.

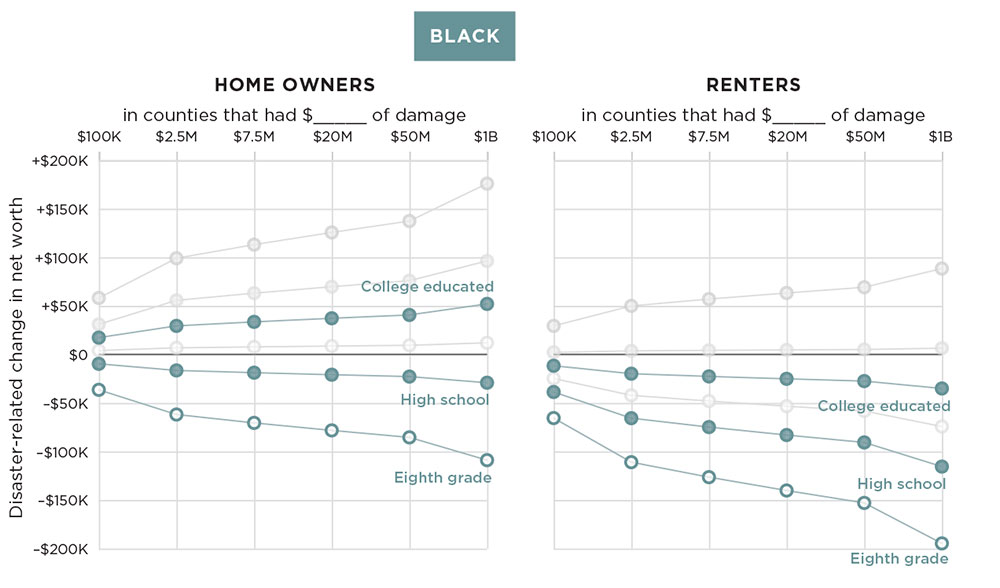

How Disasters Exacerbate Wealth Inequality

After disasters, black residents on average lose wealth and white residents gain wealth. Also, home owners are more likely to benefit than renters. This model, developed by sociologists Junia Howell and James R. Elliott, uses county-level data to show the expected change in net worth for different demographics as a result of disasters such as floods, fires, and hurricanes between 1999 and 2013.

Source: "As Disaster Costs Rise, So Does Inequality," Socius (2018)

Houston: recovery and planning ahead

Houston has long been known as one of the nation's most affordable cities. Yet this affordability is increasingly challenged by flooding.

The Memorial Day flood in 2015, the Tax Day flood in 2016, and then the vast impact of Hurricane Harvey in 2017 destroyed thousands of homes. This included a large number of apartments and homes that were "naturally affordable," such as aging apartment complexes developed in Houston's period of rapid expansion in the 1970s and '80s. One neighborhood — Greenspoint, in north Houston — has more than 5,700 of these multifamily units located directly in the floodway, according to a report from the Greater Houston Flood Mitigation Consortium.

The region's size complicates residents' search for affordable homes. The city proper covers more than 660 square miles and the region spreads out over more than 10,000 square miles. Renters and home owners who are displaced by flooding often can only find similarly priced housing in far-flung locations, which adds to their transportation costs.

Houston's work to recover from Harvey offers a key lesson: Planning for equity before disaster helps to streamline and speed an equitable housing recovery. It has several creative programs in place.

Building Citywide Affordability

Low-income households continue to experience significant challenges in finding affordable housing post-Harvey. City surveys have found that 80 percent of the households that still have "unmet needs" earn low-to-moderate incomes. As a measure of the scale of the need, the Houston Housing Authority's waiting list rapidly increased from 14,000 people before Harvey to 113,000 people afterward.

The city has an innovative plan to help meet these needs. Before Harvey hit, housing staff had already started work on a system of collaborating organizations and policies that would help reuse public land for long-term affordable housing.

It transformed the former Land Assemblage Redevelopment Authority, which acquired and held vacant tax-delinquent property, into the Houston Land Bank. That shift came with a new mission — to reuse these properties for the public good. Houston also worked with national experts and community partners to establish the Houston Community Land Trust, a citywide nonprofit organization with a mission to build long-term affordable home ownership.

The Housing and Community Development Department then took a critical third step: The agency serves as a developer for homes on Houston Land Bank property. It then conveys the built homes to the CLT when an eligible buyer selects this option. Recovery dollars from the federal government will support the city to amplify and expand this program, and help flooded low-income residents move into secure, stable, long-term affordable housing in less flood-prone areas.

The first buyer in this program, Sabrina Starks-Tarble, closed on her new house in June. The purchase price, according to a press release from the city of Houston, was about $75,000. Per the rules of the CLT, if the home owner decides to sell, she must sell at a price that keeps the home affordable for Houstonians earning the area median income.

The city sees the CLT and land bank as one of the only ways to improve housing affordability and access in general and address recovery at the same time. "If we're going to have a chance of getting ahead of the [affordability] crisis we're facing, we've got to be using techniques where we don't continually have units falling out of the affordable market as fast as we're putting them in, and the CLT is one of the few models that allows for that," Housing and Community Development Department Director Tom McCasland told the Houston Chronicle, noting that a typical CLT grants 99-year leases, which are inheritable and renewable, keeping them affordable for the foreseeable future. "This is an opportunity to actually begin to build and sustain the pool of affordable units in the city over the long run."

In a Rice University/Kinder Institute article, professor and planner Jeffrey Lowe of Texas Southern University called the CLT "a major policy intervention that would begin to ensure that lower-income residents benefit from neighborhood change."

The city is also considering using the CLT to address another systemic issue: lower-income home owners who owe years of property taxes and may not have the income to pay. In many cities, these owners would not be eligible for housing assistance.

As part of a "get to yes" policy, the city is examining allowing these home owners to place their homes into the CLT. This would allow residents to maintain continued ownership and ensure that the homes will remain affordable in the long-term when the home is sold or passed to future generations. In return for guaranteeing this long-term affordability, the owners' tax burdens would be forgiven and the homes would again be eligible for aid.

Making Recovery Comprehensive

Houston's housing department is also actively working to help those who are often left out of the recovery process — and to incorporate the same practices into their regular housing programs.

The city helps generational home owners who may not have the deed or title to a property that has been passed down through their family, or who are challenged by complicated successions that leave multiple generations of family members as technical owners of a property.

Without title to the property, home owners cannot access recovery aid, sell their homes, or access financing like home-equity loans.

According to the Center for Community Progress, these "tangled titles" are a particular problem in "low-income communities and neighborhoods with a large number of senior households." The city hires attorneys for housing program applicants who cannot produce clear title to their homes.

"[A home is] a transformational asset; you need to be able to sell it when it comes time to sell it," McCasland says.

The city is also working to actively assist renters with long-term recovery dollars. Their draft action plan for federal long-term housing recovery funds, released in 2018, dedicates nearly $315 million to the recovery of multifamily rental properties and development, or more than 30 percent of a projected $1 billion in total housing funding.

Still, challenges for renters remain: The city estimates that the actual unmet need for renters in Houston is $734 million, or more than twice the federal funding that will be available. Meanwhile, renters' FEMA hotel vouchers for short-term assistance ended in April 2018, just eight months after the storm; for low-income renters, this proved to be a particular challenge, and many could not return to their former communities.

The city will use long-term recovery resources to help rebuild affected complexes, restore quality to aging apartments, and further strategies like equitable transit-oriented development that will offer new affordable options near transit and job centers. Margaret Wallace-Brown, aicp, Houston's acting planning director, says that a core city strategy for housing equity is to "build up, not out," keeping affordable housing options and housing growth within the urban core.

'Building Forward' for Resilience

n 2018, one year after Hurricane Harvey, Houston became the 101st city (and the last) to join the Rockefeller Foundation's 100 Resilient Cities collaborative. The Resilient Houston strategy will be complete in late August 2019, the second anniversary of Harvey.

The strategy's five "discovery areas" include one focus area that combines housing and mobility, which deals with housing affordability, minimizing sprawl, and creating housing in the urban core where it is most needed.

As a planning effort, Resilient Houston is taking a holistic view of recovery needs and helping Houston to "build forward" in ways that minimize the impacts of future storms.

Houston's experience illustrates the importance of planning for housing equity before and after a disaster in order to reach more equitable housing recovery outcomes. Their work to understand local housing needs and establish creative programs before Harvey hit has allowed them to quickly put recovery dollars to work.

Their resilience planning efforts, meanwhile, are ensuring that recovery dollars are enhanced with other sources of funding, and that funding will benefit residents now while protecting people from future disasters.

Alexandra Miller is a managing principal and the community development lead at Asakura Robinson Company, an urban planning, urban design, and landscape architecture firm. She lives in New Orleans. Jeffrey Goodman is a planner and designer based in New Orleans. His research focuses on short-term rental policy, regulating the sharing economy, and public history.