Planning December 2019

Planning for Future Leaders

Involving diverse youth in planning now means they’ll be engaged community members later — and maybe even become planners themselves.

By Juell Stewart

When Katanya Raby was in second grade, her class read The Little House, a book about a city slowly overtaking a countryside home. It was the first time she ever considered the complexities of rural and urban environments. Those thoughts developed into a natural curiosity about the built environment that eventually led her to pursue an undergraduate degree in architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago. But it wasn't until her junior year, during courses in sociology and anthropology, that she identified the career she wanted. "I had [always had] interests in planning, but I didn't know what it was until then," she says. After learning about the profession, she went on to earn a master's degree in urban planning and policy from UIC.

Raby's experience isn't uncommon. Many would-be planners only learn about the profession through more well-known disciplines like architecture or public policy — a massive missed opportunity, says Raby, who heads up the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning's Future Leaders in Planning program, also called FLIP.

"Just because planning is a silent profession, kids aren't exposed to it like doctors and firefighters. We don't wear a special suit," she says.

![Planning December 2019 Planning for Future Leaders Design to Better [Our Community] youth leaders take a break for a group photo while canvasing the Grand Center Arts District to ask community members what they would like to change about St. Louis. Photo courtesy Creative Reaction Lab.](https://planning-org-uploaded-media.s3.amazonaws.com:443/image/Planning-2019-12-image08.jpg)

Design to Better [Our Community] youth leaders take a break for a group photo while canvasing the Grand Center Arts District to ask community members what they would like to change about St. Louis. Photo courtesy Creative Reaction Lab.

Youth engagement programs like FLIP present a critical opportunity to fix that problem by building pathways to planning, especially for youth of color.

"Historically, the industry has been a white, male-dominated profession," Raby says. "Our young people of color should know that there are people like them who work in this field and contribute to the development of infrastructure, housing, economic development, art and culture, and all of the other planning efforts in their communities."

Representation can be a vital part of deciding which career to pursue, explains Raby, who initially decided architecture was an attainable field after meeting an architect who was Black, like her. "I was unsure as to whether I could actually be successful until I met him," she says. If Raby had been exposed to planning and Black planners then, she might have found her calling much earlier, she says. "I would have seen myself in those spaces, which would have likely identified planning as the career that was best suited for me much earlier."

Youth engagement programs also address the structural barriers that prevent young people from engaging in formal outreach processes by translating the language of planning and the complexities of civic participation in a way that empowers them to take active leadership roles within their communities. "It is important for youth to see the ways in which our communities are shaped and see that they, too, can be part of the process," Raby says.

The bottom line: The earlier youth are introduced to planning principles, the sooner they can begin building both their future careers and communities.

Ernie Wong of Site Design Group and 2019 FLIP participants discuss urban design elements of Ping Tom Park in Chicago's Chinatown neighborhood. Photo courtesy CMAP staff.

Planning 101 in the Windy City

CMAP originally started FLIP in 2011 as a one-time program, part of the agency's "Invent the Future" youth outreach strategy for its GoTo2040 regional comprehensive plan, but once CMAP's board saw how refreshing it was for staff to engage with youth, they decided to invest in it as a major component of the metropolitan planning organization's work.

FLIP works with high school students of diverse backgrounds from across CMAP's seven-county Chicagoland region, creating a way for kids to learn about what makes the world (and city) around them tick — and the language they can use to describe it. The curriculum uses urban planning as a vehicle to get students to contemplate the deeper social issues that undergird policy decisions and urban development. For Raby, it boils down to one guiding question: "How can we get students to have these conversations earlier and think strategically about how we can build our next generation of leaders?"

Each summer, a maximum of 45 students, eight CMAP staffers, and six interns come together for a six-day program, including a final ceremony and open house for students to show off what they've learned to their families and friends. Students spend the first day getting a Planning 101 crash course. Days two through five are based around four "scales of planning" in increasing order of size: site, neighborhood, municipal, and regional. This helps gradually build students up to understanding the role CMAP plays as the regional planning organization for the Chicagoland area.

The summer 2019 FLIP cohort focused on transportation, site planning, and community engagement. To give a sense of how much FLIP students experience in just one week, day two focused on site planning at the recently renovated 95th/Dan Ryan Chicago Transit Authority train station. Throughout the day, they went on a tour of the station led by CTA's vice president of infrastructure and maintenance, met with the Metropolitan Planning Council about the organization's community engagement process for the station, and met with a community organization about plans to redevelop a CTA-owned site adjacent to the station. To wrap up the day, students took what they learned about the community and its surrounding neighborhood to sketch their ideas for revitalizing the site.

"It's rewarding for me personally because we're not just building a pipeline of planners, but we are also [fostering] some really great civic discourse among young people," Raby says.

At a recent boot camp, FLIP participants worked with UIC's College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs to map disparities in transportation access across Chicago. In this way, FLIP's curriculum is designed specifically to expose students to the legacies of inequality and structural racism that often accompany public policy and planning decisions, and to give them the tools and language to combat them early on in their education and careers.

Small Scale Youth Engagement

Planners don't need to create a formal program to connect with youth. Jonathan Pacheco Bell is a public-sector planner in Los Angeles County from Boyle Heights, a traditionally Latinx LA neighborhood that has recently undergone significant gentrification and displacement. An integral element of Pacheco Bell's professional philosophy is a practice he calls "Embedded Planning" ("We Cannot Plan From Our Desks," Viewpoint, October 2018), which implores planners to spend most of their time building relationships in the communities they plan for through what he calls "street-level engagement."

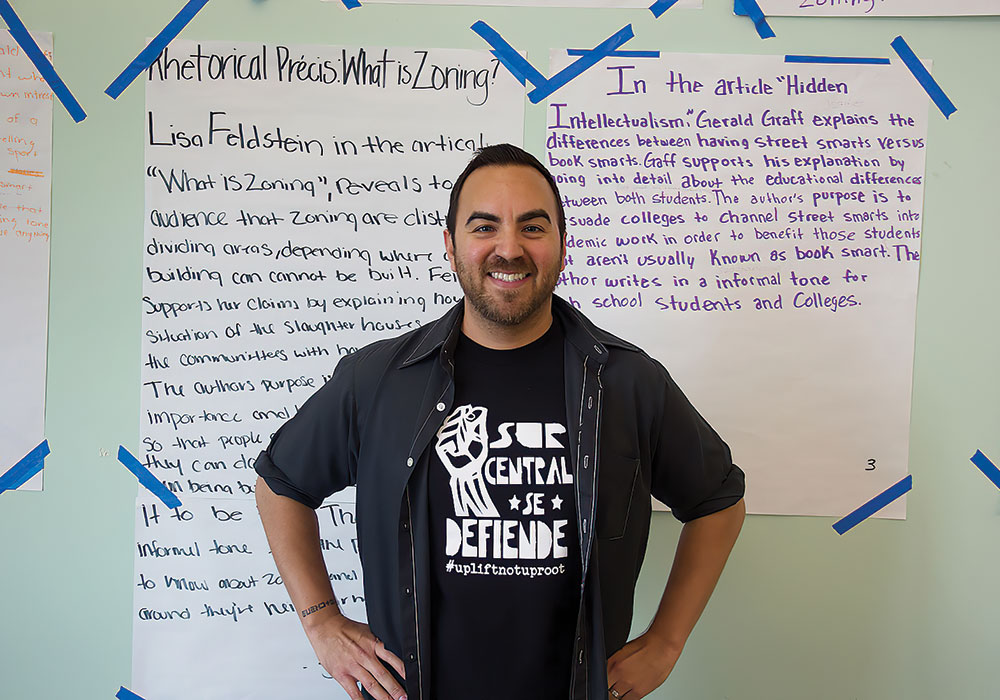

Jonathan Pacheco Bell stands with work by 12th-grade students at East Los Angeles Renaissance Academy. Their project examined zoning history and planning theory concepts. Photo courtesy Jonathan Pacheco Bell.

A graduate of UCLA's Master of Urban and Regional Planning program, Pacheco Bell has used his evenings and weekends to serve as a mentor at his alma mater for the past 12 years. Pacheco Bell has also been assisting educators at East Los Angeles Renaissance Academy — an urban planning program within LA Unified School District's Esteban Torres High School — for the past two years. He says that the common thread among the youth he's engaged with is that they are "excited, curious community members who are interested in community planning." Pacheco Bell believes in inspiring young people with the ability to start dialogues to better understand and grapple with the complexity of urban phenomena happening in the world around them.

This method of addressing the "theory-practice gap" in community planning not only gives students insight into building educational and career pathways, it's also an opportunity to help students have their voices heard, he explains. "Young people are fundamentally a part of the daily life and the fabric of the neighborhood."

Building a future society

The planning profession struggles with a lack of diversity. According to a 2018 survey conducted by the American Planning Association, only about 13 percent of APA members identified as Black, Hispanic, or Asian/Pacific Islander combined. That lack of diversity within the profession has hurt the planning practice at every level.

"If the people who are providing these services to communities have no connections to those they serve, important issues within that community can and will be overlooked," says Raby. "People of color, more specifically Black people, have been left out of planning processes since the beginning of formalized planning in the U.S. Stemming from systemic racism and racist practices from civic leaders and anti-Black planning initiatives, communities of color have been planned for (or not planned at all) by outsiders and are left to work with what has been given."

Talking to youth about culture, space, and inclusion is a vital aspect of ensuring that the next generation of planners reflects the demographic realities of the communities they plan for and helps break that cycle, says Brittney Drakeford, senior planner for the Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission in Upper Marlboro, Maryland.

Drakeford grew up in Prince George's County, Maryland, whose population is predominantly Black, with Latinx residents comprising the second largest population. Along with several people who currently work for the Prince George's County Planning Department, her introduction to planning came from the department's longstanding Collegiate Internship Program, a full-time, paid professional development program for college and graduate students interested in public-sector planning.

But as a 2017 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health Leader, Drakeford saw an opportunity to develop the youth outreach programs she would have wanted. "As someone who grew up in the community I currently serve, I wished that I had an opportunity to engage with planners when I was in high school," she says.

Using her experience in youth development for arts-based and civic engagement organizations, she developed the Remix the Block youth engagement curriculum in 2019 in partnership with the Planning Commission, Prince George's County Memorial Library System, and the county's public school system. The program focuses on space, creativity, and inclusion and is aimed at expanding opportunities to high schoolers. It's also specifically designed to attract those who may not be familiar with urban planning. Drakeford sees it as her contribution to youth mentorship, particularly as a way to introduce urban planning fundamentals to Black youth.

"I really see planning as an act of futurism and building a future society," says Drakeford. "For this reason, if we want to see young Black people in our future society, we have to give them the opportunity to have a voice and choice in that future."

The inaugural program took place this past summer and centered on the Remix the Block tool kit. For six weeks, high school, undergraduate, and graduate students explored development patterns throughout the county, took deep dives into various communities, and ultimately presented their recommendations to planning department staff.

The results of the program are promising, Drakeford says. Some of the students' recommendations have since been forwarded to local stakeholders, and meetings have been set up to discuss their feasibility. Several participants even expressed interest in applying for planning master's programs or exploring career paths in demography and geography.

Remix the Block summer interns share what they've learned with planning department staff in Prince George's County, Maryland. The county has a full-time, paid professional development program for college and grad students interested in planning. Photo courtesy Brittney Drakeford.

Intersectional planning

Young people have a natural curiosity about the world around them, and youth programs like FLIP and Remix, and others can fuel that curiosity by engaging young people around issues that are relevant to them and connecting them to planning. Topics of particular interest to youth include the effects of gentrification, drivers of homelessness, and active transportation modes.

According to Drakeford, "[Walkability and bike-ability are] inherently a youth issue, as kids are unable to drive around a community. All of the youth groups that I've worked with constantly ask for enhanced improvement to the street grid and to the sidewalk infrastructure."

In Missouri, the Creative Reaction Lab's Community Design Apprenticeship Program encourages college-aged Black and Latinx youth to explore hyperlocal topics of their own choosing and to own the process of creating community design solutions.

Antionette D. Carroll started Creative Reaction Lab after her family moved out of Ferguson, Missouri, six months prior to the unrest that unfolded in the city in the wake of the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in 2014. Seeing the critical need to catalyze "creative problem solving," she wanted to devise a program to educate and empower youth to create change in their communities.

The program began as a three-month apprenticeship but is being expanded into a nine-month model that exclusively admits formerly incarcerated youth. By challenging participants to think about the connections between different design approaches in the built environment, they can look deeper into the role of power dynamics in shaping different spheres like politics, policy, and the arts.

"I always saw a disconnect between the design space and its role in power," says Carroll. CRL implores youth to be innovative in addressing these issues as they relate to their own communities.

The spring 2018 cohort of Community Design Apprentice — the program's first — explored the theme "Mobility for All by All" in the St. Louis Kings Highway and Fairground neighborhoods in partnership with Washington University. For 10 weeks, five young African American men from North County and East St. Louis trained in CRL's signature Equity-Centered Community Design process, which offers a foundation on collaborative, creative problem solving and designing with — not for — others. The framework also incorporates factors like equity, humility, and power dynamics into the problem-solving process.

By having conversations with residents in key community anchor institutions, the apprentices uncovered a gap in community awareness of a proposed expansion of the city's MetroLink light rail: Despite the transit agency's outreach efforts, residents were still unaware of the implications of the project, which highlighted concerns about the effectiveness of outreach methods.

The apprentices used their background research and creativity to develop a community-centered pop-up called "Community + Transit: A Participatory Art + Design Experience," which included an interactive art installation and an "idea wall" that invited residents to share thoughts about the impact of transit on their lives. Through designing a new engagement process, residents who were previously uncomfortable sharing their thoughts were empowered to voice their concerns about the transit expansion's potential effect on housing affordability, property values, and displacement.

At press time, the fall 2019 program was slated to focus on addressing gun violence and limited food access in the St. Louis region.

"[CRL's] mission isn't to be urban planners, but in the work that we're doing, we have students think about the intersections of racial and health inequities and how they're related to infrastructure and policy," says Carroll.

5 Tips to Attract Youth to Planning

1. TRUST AND LISTEN TO YOUNGER RESIDENTS

People have an innate ability to describe the conditions in their communities, regardless of age or education level. If you show young people that their perspectives are valuable, they will feel more empowered and invested in the process.

2. DITCH THE JARGON

Planning is rife with technical terms that can pose major barriers to young people. Break down concepts to fit each of your target age groups.

3. GET OUT OF THE CLASSROOM!

Kids and teens want to understand how concepts apply to the world around them. Get creative and develop on-site, place-based outreach opportunities that directly connect young residents with the community issues that resonate with them.

4. WORK WITH UNIVERSITIES ...

... and alumni groups to connect current students and recent graduates with professional planners. Be sure to consider opportunities to engage students in urban issues outside of the traditional planning discipline in departments like political science, sociology, and environmental science.

5. PARTNER WITH SCHOOL DISTRICTS ...

... library systems, and other local institutions that directly interact with youth. Engaging young people alongside their parents can maximize the effect of your outreach.

This type of intersectional approach allows the organization to interrogate the power structures at play in the design space, and to see how decisions can impact quality of life, life expectancies, and other critical metrics that go beyond the typical understanding of the built environment. CRL challenges the status quo by elevating urgent issues that affect the daily lived experiences in communities that aren't typically directly addressed within the planning context, such as racial equity.

One of CRL's flagship programs, the Design to Better [Our Community] Program, began as a summer academy but is expanding to include classroom curriculum to help high schoolers develop a deeper understanding of the concepts throughout the academic year. Students go on field trips, meet local civic leaders, and get funding to come up with an innovative civic design idea.

One unique aspect of the program is that participants are provided with food, transportation, and a stipend. "It's really important that we pay people for their time," Carroll says, adding that a stipend shows that they're considered a priority and that the time they spend working on civic issues is valuable.

Ultimately, CRL's mission is to build a pipeline of empowered organizers, activists, and civic leaders.

Members of the Youth Advisory Board of Larkin Street Youth Services and YEP! work with volunteer planners during the 2019 National Planning Conference in San Francisco to develop strategies for planning for homeless youth. Photo courtesy YEP!

Planning's win-win

As much as these programs are centered on exposing youth to planning principles, they've also been useful in getting planners and planning departments out of their comfort zone to see their communities from a different perspective.

"We have a lot of planners who can engage with communities, but when it comes time for youth engagement, they're scared," says Corrin Wendell, who cofounded Youth Engagement Planning, or YEP!, along with Monica Tibbets-Nutt.

YEP! provides planners with a curriculum that not only teaches children as young as five about planning but shows planners how to bring youth into the planning process. Activities can be customized to fit any grade level — from kindergarten students learning how to identify their neighborhood on a map to high schoolers learning compromise through community engagement.

YEP! works with a network of volunteers and youth organizations across the country to conduct local youth workshops; they also offer curriculum resources online.

Wendell says that because planners spend much of their professional lives working in highly specialized areas, spending time with youth can help them emerge from their technical silos and rediscover how to connect with nonplanner audiences, including nonnative-English speakers.

"It's surprising how hard it is to get planners to speak in plain English in a way that people understand. By breaking down things for kids, I think it helps [planners] see communication gaps with the general public," Tibbets-Nut says.

YEP! relies primarily on an extensive network of volunteers, including graduate students and planning professionals who participate in Planning Day in School events in K-12 classrooms nationwide.

Recently, Ramsey, Minnesota, sought YEP!'s help to develop a method for incorporating youth into its comprehensive planning process. The city hosted a community outreach event and YEP! worked with a local arts organization to provide youth with large canvases so they could illustrate what they'd like to see in their community. Not only were they used to inform the plan, they were also assembled and displayed in city hall.

And just last spring, at the 2019 National Planning Conference in San Francisco, YEP! partnered with Larkin Street Youth Services, a local nonprofit that provides housing, education, and other support services for homeless youth. Ten planning professionals from across the U.S. visited the Tenderloin neighborhood and met with the organization's Youth Advisory Board members, who range in age from 18 to 26, to teach them about the planning processes that they've been historically excluded from. The goal was to develop a strategic plan that elevates their voices in the community planning process. The interactive workshop focused on community building between planners and youth and explored the foundations of city planning, the advocacy work that homeless youth were engaged in, and facilitated group discussions.

That engagement helps planning departments, too. Thanks to the youth engagement and outreach efforts that sprang from FLIP, CMAP has changed how they work as they develop their OnTo2050 regional comprehensive plan. The regional planning organization has created more formal opportunities to get feedback from youth (which they define as anyone under 26) as they look for new, creative ways to approach the stark disparities experienced by Black and brown communities in the region. CMAP has also hosted other organizations, including the Atlanta Regional Commission, that are interested in implementing programs similar to FLIP and have been highlighted as leaders in youth engagement by the National Association of Regional Councils.

For planners working with youth, the nature of the work is collaborative, and there's a growing interest in sharing strategies and resources, Raby says. She would like to see them grow into a larger movement. "I'm hoping that FLIP and other youth engagement programs within planning continue to grow and be a force."

Juell Stewart is a city planner, policy researcher, and freelance writer based in San Francisco.