Planning November 2019

Credit Limit

Tax code changes made LIHTCs less valuable, which means funding affordable housing is even harder.

By Jake Blumgart

For a generation, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit has touched most affordable housing projects in the U.S. The program, created in 1986, gives tax breaks to those who invest in rental housing production for poor and working-class Americans. Developers raise equity for affordable projects by selling tax credits to private investors, allowing them to reduce their corporate tax liability.

The program has created or preserved 2.3 million units of affordable housing over the last 30 years, according to the Urban Institute, but the value of the credits is vulnerable to economic downturns. Changes to the tax code can also put the program's viability at risk, particularly if lower corporate tax rates across the board make tax breaks, like LIHTCs, less appealing because they are less necessary to investors' bottom lines.

That is exactly what's happening in the wake of Congress's recent tax reform. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, passed in December 2017, lowered the corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent. As a result, the value of individual tax credits have fallen from $1.05 per credit in November 2016 to 94 cents per credit (a slight rebound from the depths of uncertainty in 2018, when credits were only worth 90 cents each), according to Novogradac & Company, a consultancy that tracks the LIHTC industry closely.

In Raleigh, North Carolina, the developer of the Village at Washington Terrace (foreground, 16 buildings in complex — 14 residential, 1 community center, 1 childcare center) and Booker Park North (top right) had to make up funding shortfalls after federal tax cuts. Photo by Farid Sani Photography.

Village at Washington Terrace

UNITS: 162 units of affordable housing

LIHTC USED: 4%

2017 TAX CHANGE DEFICIT:

$1,403,013

Booker Park North

UNITS: 72 units of affordable senior housing

LIHTC USED: 9%

2017 TAX CHANGE DEFICIT:

$902,910

Experts have been watching and wondering how it all will play out, particularly amid the U.S.'s worsening housing affordability crisis.

"There continues to be strong demand for low-income housing tax credits by investors, [but] the changes to the tax code did result in less investment for any particular project," says Scott Hoekman, president and CEO of Enterprise Housing Credit Investments, a subsidiary of the national nonprofit housing organization Enterprise Community Partners, "which then created a financing gap that needed to be made up elsewhere."

For projects that were already in the LIHTC pipeline as tax reform negotiations played out, the drop in LIHTC value wasn't the only hurdle. The several months of uncertainty caused a domino effect of delays and increasing construction costs that affected bottom lines even further. Developers and state and local officials had to get creative to fill the gaps and keep projects viable.

We were scrambling," recalls Joseph Portelli, vice president of development for the RPM Development Group, an affordable housing provider in New Jersey. "The concern ranged from whether or not there would be a program at all to how pricing for tax credits might change."

RPM's 330-unit mixed-income housing development in Jersey City was one of the projects left in the lurch. The project depended on four percent LIHTCs, which generally account for 30 to 40 percent of a project's cost. The rest is made up of a complex stack of other funding sources like private activity bonds, loans, deferred developer fees, to name a few. (There is also a nine percent LIHTC that covers as much as 75 percent of a project's costs.)

State and local authorities in New Jersey have struggled to fill the gap for RPM and other affected projects. The New Jersey Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency allowed developers to apply for state-backed "hardship credits" that were specifically designed to make up the difference left by price reduction. They also increased their caps on per-unit development costs by $25,000, to accommodate increased costs of supplies caused by the Trump administration's trade wars. Municipal authorities, Portelli reports, have waived or reduced fees for permits, water, and sewer connections, but purely on a case-by-case basis.

The Whitlock Project in Jersey City, New Jersey. Photo courtesy RPM Development Group. "We were scrambling," said Joseph Portelli, vice president of development, RPM Development Group. "The concern ranged from whether or not there would be a program at all to how pricing for tax credits might change."

Mind the gap

As in Portelli's case, to try to fill the funding gap for current projects left by the federal government's inaction and LIHTC's weakened state, affordable housing developers across the country are turning to local and state authorities for help.

Solutions are forthcoming because local policy makers are vigorously reacting to the pain of local affordable housing providers — even though local authorities can't hope to fully meet housing needs on their own. But even if existing projects are saved, the long-term implications for the program are unclear.

"Our analysis indicates that fewer units will get financed overall, because the resources to make up the gap are limited as well," says Hoekman.

Hoekman says it's too early to say just how many fewer units are being produced in the wake of the corporate tax cuts. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 passed at the very end of that year, and housing development projects usually take at least 20 months to wend their way through the development process.

But there are estimates. In December 2017, Novogradac approximated that tax reform, as passed, would reduce the number of affordable rental housing units developed between 2018 and 2028 by 16 percent (losing 232,000 from a projected 1,493,000).

Practitioners on the ground say that they are definitely feeling the pinch. In North Carolina, Michael Rodgers of the affordable housing developer DHIC says two of his projects were greatly complicated by the corporate tax cuts of 2017.

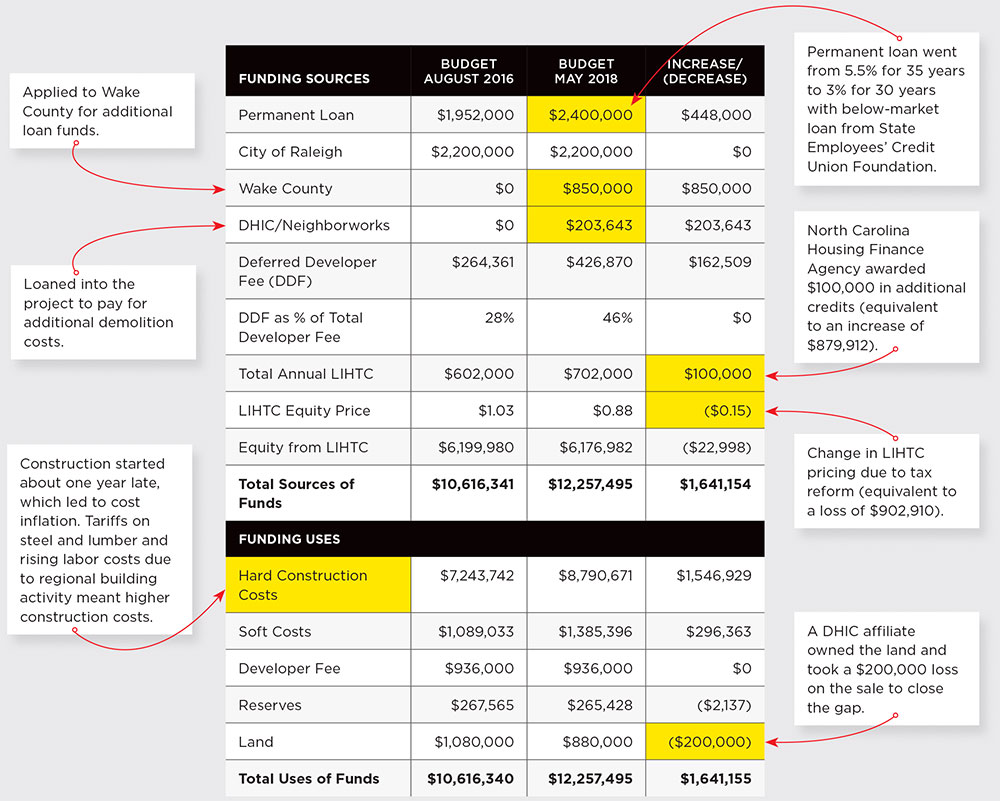

The Booker Park North project is bringing 72 units of senior housing to Raleigh — using nine percent LIHTCs — while the larger Village at Washington Terrace will provide 162 units of affordable housing using four percent tax credits. Both projects applied for LIHTCs before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed. After the legislation passed, Rodgers saw the value of the tax credits fall by about 10 percent on the two projects.

"Both [projects] suffered during tax reform because neither one had closed yet," says Rodgers, who is a project manager with DHIC. "[W]e had to undergo a flying-by-the-seat-of-our-pants rescue to figure out how to move forward and keep them alive," he says. "We lost between 13 to 15 cents on the dollar on what the equity price was going to be."

To stay on course, DHIC approached the North Carolina Housing Finance Agency, hat in hand, and explained to the state authorities that tax reform had imperiled the subsidy package they'd worked out to ensure the projects' feasibility.

The state bureau granted them (and all other projects with a nine percent LIHTC allocation) an additional allotment of $100,000 from future tax credits they expected to receive, while Wake County (where the projects are located) gave an additional $850,000. Then $200,000 was taken off the price of the land — which was owned by a group affiliated with DHIC — and the price of the loan was reduced by getting a lower interest rate loan from the State Employees' Credit Union.

The developer also loaned $203,000 to the project from a one-time grant they received from Neighbor Works: Project Reinvest, a project of a national network of community development corporations.

The crisis was averted, but the threat to affordable housing developers remains. DHIC has been around for more than 40 years and is one of the Research Triangle's largest affordable housing providers. Can other, less established providers work the same magic? Can DHIC reliably count on such largesse in the future? After all, the state finance agency's grant of additional tax credits came from the next year's supply — meaning there will be fewer available low-income housing tax credits for other projects.

"Across North Carolina, if not elsewhere, you are seeing fewer allocated projects than you would have in 2014 or 2015," says Rodgers. "In an environment of rising construction costs and falling tax credit equity prices, our financing is getting thinner even as our construction needs are getting greater."

Mind the Gap: Adjusting to Funding Shortfalls and Cost Increases

Booker Park North in Raleigh, North Carolina, was awarded a nine percent LIHTC in August 2016 to construct units for low-income seniors. Tax reform, tariffs on building materials, and a labor shortage combined to cause a significant funding gap that threatened the viability of the project. DHIC, the developer, made concessions and worked with local and state governments to make up the shortfall, and the project was completed in June 2019.

Source: Michael Rodgers, DHIC

Alternative methods

Local governments see that all of this is occurring in an atmosphere where the need for affordable housing is on the rise, especially in hot markets like the Research Triangle of North Carolina.

Rodgers says the municipal, county, and state governments he deals with understand the housing crisis and LIHTC's circumscribed ability to address it. In his region, numerous municipalities have put forward bond referenda on the ballot to fund affordable housing.

Last year Chapel Hill, by far the smallest of the Research Triangle's three cities, approved a $10 million bond referendum for local low- and moderate-income projects. This month in Durham, voters will decide on a $95 million bond for affordable housing, which the mayor bills as the largest effort in the state's history.

The region's largest city, Raleigh, is considering a similar referendum which pro-housing city council members want to stretch to between $50 million and $120 million. At the end of 2018, Wake County created the Housing Affordability Department, funded by a property tax increase that should give the new agency $15 million a year.

Rodgers says there have also been attempts to ease administrative burdens. In Chapel Hill, Rodgers says the town allocated a staff person to one of their projects and quickly shepherded it through the bureaucracy. In Durham, the city manager declared one of their initiatives a "priority project" and moved it through the development review process with unusual speed.

"Construction costs are rising rapidly, so a few months makes a big change in construction costs," says Rodgers. "[They've tweaked] the permitting and development review process to ensure a much shorter time frame. At the end of the day, that's what's essential to keeping our projects on schedule and on budget.

Portelli of RPM Development Group says he's seen some of these trends in New Jersey, although, unlike in North Carolina, the legislature is considering a variety of affordable housing bills, including an inclusionary zoning requirement for those who get public aid on their projects.

In cities like Austin, Texas; Portland, Oregon; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Berkeley, California, bond referenda secured additional funding for affordable housing last year. In California, a statewide ballot referendum secured an additional $4 billion for affordable housing across the state.

And Congress hasn't been entirely ineffectual. In the March 2018 federal omnibus bill, a temporary 12.5 percent increase in LIHTCs was approved. Novogradac estimates this will increase affordable housing production over the next 10 years by 28,400, making up about 12.8 percent of the units the firm estimates will be lost due to the 2017 corporate tax cuts.

But developers face further headwinds. President Trump's trade policies have driven up the cost of building materials like soft wood, steel, and aluminum. Meanwhile, the continued pace of market-rate construction in many regions has sent the cost of labor spiking as well, making it harder for already struggling affordable housing developers to complete with their more conventional counterparts.

Future uncertain

In short, affordable housing developers and industry observers say that the sector hasn't been decimated by tax reform. Instead, they've suffered yet another setback when they were already outmatched by the need before the Trump administration even took office.

"The biggest obstacle is that there just aren't enough credits issued. It's highly, highly competitive and just getting more dire every day," says Woo Kim, aicp, a principal with the planning and urban design firm WRT. "We aren't reforming this program at a national level to actually keep up with housing affordability issues."

As the 2020 election nears, housing policy has begun to inch toward the national limelight again. A handful of the Democratic presidential candidates have put forward housing platforms, including Kamala Harris, Cory Booker, and Elizabeth Warren, who proposes close to $500 billion in federal housing programs, although not through LIHTC.

Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) says she wants to expand LIHTC, although her exact plans are not clear. Most substantially, for the LIHTC program, is Julián Castro's proposal to expand the program by $4 billion a year while offering loan programs to incentivize more municipalities to accelerate development review for these projects (like Durham and Chapel Hill have done).

But experts say these changes are quite small compared to the bold visions the Democratic Party's presidential candidates have been taking on issues like health care and climate change.

"I'm hearing some good ideas from presidential candidates, but I don't think they are going to make a big enough dent," says Kim, who argues that in many of the nation's most dire housing markets the LIHTC program could be quadrupled in size.

"I think what we need in this country is a Works Progress Administration-type initiative for housing," says Kim. "A lot of resources need to be devoted to this and it needs to be at the federal level. That's the only way to solve the housing crisis."

Jake Blumgart is a reporter based in Philadelphia.

Resources

The Urban Institute's cost of affordable housing tool explains why building it is so expensive.