Planning August/September 2020

The Heat Is On

With climate change pushing temperatures ever higher, cities must develop plans for extreme heat — especially in places with vulnerable populations.

By Amy Sherman

When it comes to dangerous weather events, hurricanes and tornadoes draw a lot of attention because of the destruction they create. Those storm events can set off a recovery chain reaction culminating in presidential disaster declarations and federal funds.

But that's not the case with extreme heat. While cities can apply for grants, solicit donations from the private sector, or get research assistance from universities, they are largely on their own to figure out how to pay for creating and implementing plans. And while cities have been planting trees and encouraging installation of green roofs and surfaces that trap less heat over the past few decades, experts say it's nowhere near enough.

Most cities have overall hazard mitigation plans, many of which include elements for heat waves, says Brian Stone Jr., an urban environmental planning and design professor at Georgia Institute of Technology. But what's needed are specific urban heat management plans or climate adaptation plans that focus on strategies like modifying the design of cities to lessen heat intensity for the long term, he says. That's because it's only going to get hotter.

Photo by stevanovicigor/iStock/Getty Images Plus.

According to the 2019 Union of Concerned Scientists report Killer Heat in the United States, extreme heat days — when temperatures top 90°F, 100°F, or 105°F — are expected to exponentially increase in the next few decades if the current global emissions path continues. By 2036 alone, the average number of days per year with a heat index above 100°F will more than double.

"If we wish to spare people in the United States and around the world the mortal dangers of extreme and relentless heat, there is little time to do so and little room for half measures," the report says. Cities need to take significant steps now to develop long-term resilience plans, especially for the communities most vulnerable to rising temperatures.

A performer cools off at the Des Moines, Iowa, Farmers Market during a heatwave in 2019. In the U.S., the average number of days per year with a heat index above 100⁰F is expected to double by 2036. Photo by KC McGinnis/The New York Times.

The deadliest disaster

Extreme heat already causes more deaths than any other weather-related hazard — more than hurricanes, tornadoes, or flooding, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That's despite the fact that the number of heat-related deaths are likely undercounted, because death certificates may not reflect it as the cause. For example, while no official death toll has been calculated for Chicago's disastrous 1995 heat wave, only 465 of the estimated 739 deaths that occurred were legally attributed to the hazard.

And as projections warn of an increase in hotter days, they also predict increased health risks. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, as the number of people experiencing 30 or more days with a heat index above 105°F in an average year surges — from just under 900,000 now to more than 90 million, or one third of the U.S., by 2036 — an additional 9,300 heat-related deaths across the country can be expected annually.

City dwellers are especially at risk. Fewer trees and more impervious surfaces that retain heat, like asphalt and pavement, lead to the urban heat island effect, creating air temperatures up to 22°F warmer than nearby areas without those conditions — and greater risk of serious health impacts. Phoenix, the hottest urban area in the U.S., saw 182 deaths attributed to heat-related issues in 2018 alone.

"Temperatures in the region have continued to rise, and, unfortunately, the number of heat-related deaths has continued to rise each year in the last five years," says Mark Hartman, the city's chief sustainability officer.

In Phoenix and elsewhere, unhoused people, the elderly, and outdoor workers are among those most at risk of heat-related deaths. Low-income residents and communities of color in areas with long-term disinvestment are also disproportionately vulnerable. Of the 465 people whose cause of death was officially recorded as the record-breaking 1995 heat wave in Chicago, nearly 85 percent were over the age of 60, while Black Chicagoans were 150 percent more likely to die than white residents.

Fifteen years later, those disparities are still seen. They can in part be traced back to racist policies like the decades-long practice of redlining, in which the Federal Housing Administration, banks, and other lenders segregated neighborhoods by race by denying mortgages to Black applicants and other people of color. More than 50 years after the practice was officially killed, its impacts live on. Communities of color, particularly Black and Latinx communities, have seen routinely less investment, including in amenities nearby white-majority neighborhoods enjoy, like lush park space and thick tree canopies — elements that reduce the urban heat island effect. A 2020 study published in the Journal of Climate found that in 94 percent of the 108 cities analyzed, formerly redlined neighborhoods are on average five degrees hotter than nearby areas. And in some cities across Oregon and Colorado, that difference can top 12 degrees.

On balance, the impacts of extreme heat expose the underlying racial and socioeconomic disparities in the U.S., says Rachel Cleetus, policy director of the Climate and Energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists. Access to air conditioning, for example, can prevent heat-related illness and injury. But according to the U.S. Department of Energy, about a quarter of American households lack access to it due to financial reasons, or because their housing does not provide it. While the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development recommends that local public housing authorities grant requests for air conditioning, they do not require that it be provided, a HUD spokesperson says. HUD has no data to show what percentage of public housing provides air conditioning.

And even households with air conditioning might not use it because of to old, faulty equipment or utility costs. A recent article in the Journal of the American Planning Association found that the average low-income household has an energy cost burden of seven percent, versus just two percent for higher income households.

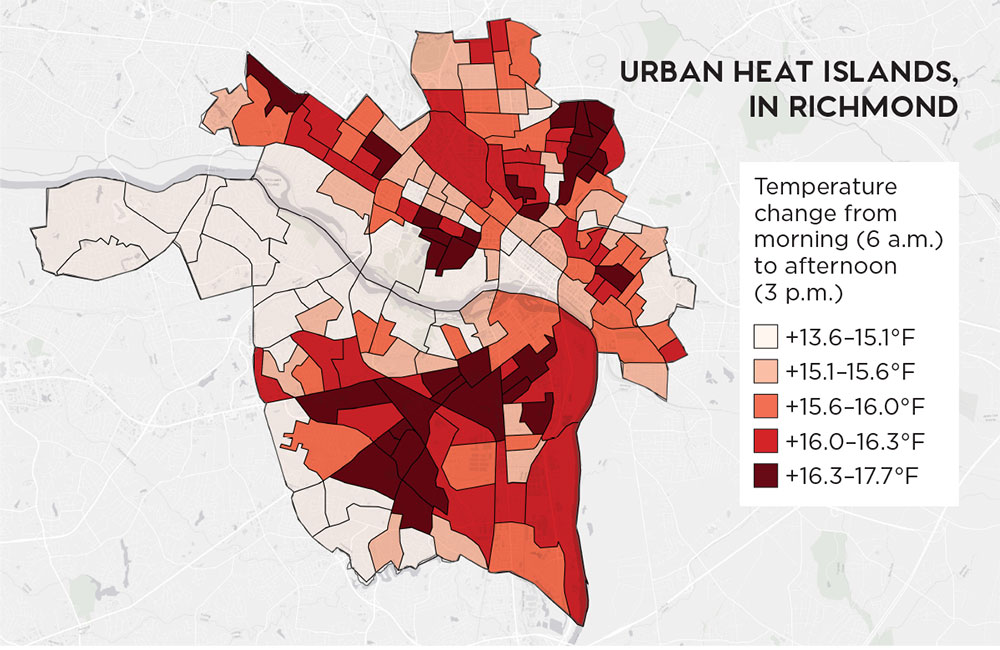

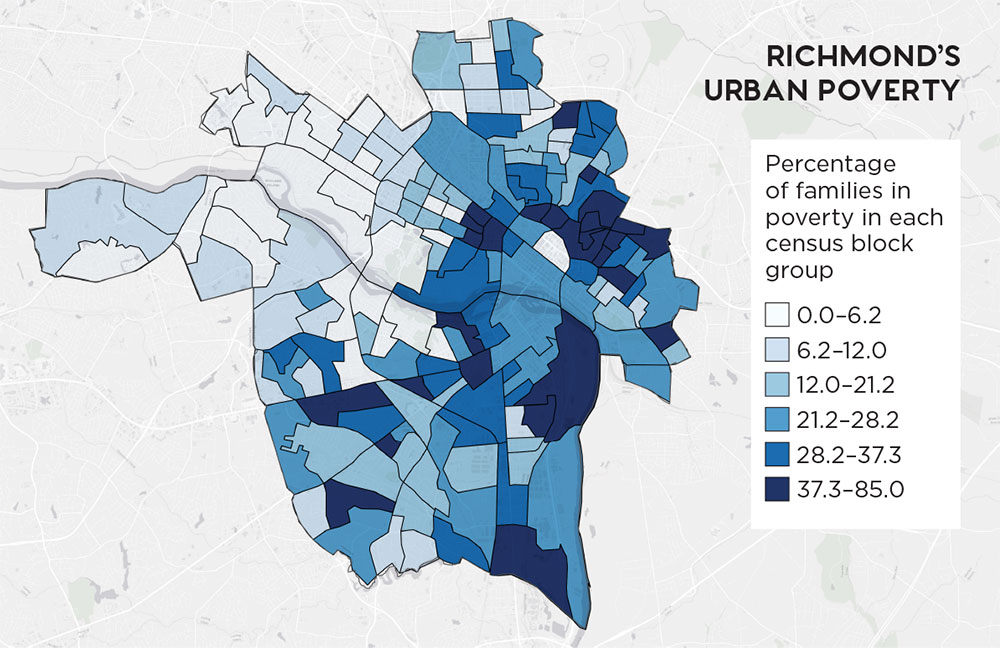

It's Hottest Where It's Poorest

A study from the School of Urban Studies & Planning at Portland State University and the Science Museum of Virginia in Richmond looked at the variances between urban heat and the landscape features in different neighborhoods. The microclimates of lower-income areas with fewer amenities like parks and tree cover experience higher temperatures.

Census Block Source: American Community Survey 2011–2015; Maps: Integrating Satellite and Ground Measurements for Predicting Locations of Extreme Urban Heat, courtesy Jeremy Hoffman.

Urban heat management

"Given that even dramatic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions would not substantially slow global rates of warming for many decades, urban heat management is among the only viable approaches we have to lessen the principal health threat of climate change: extreme heat," says Georgia Institute of Technology's Brian Stone. "Urban heat management will soon emerge as a major and critical focus of climate adaptation planning in all large cities of the U.S."

Some cities are beginning to recognize that — and take action. Stone points to New York City's Cool Neighborhoods NYC plan as a model for heat mitigation planning because it addresses the three dimensions of heat vulnerability: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.

Exposure is determined by land surface temperature data derived from satellites, which allows the city to determine the most impacted neighborhoods. Sensitivity pertains to the susceptibility of residents within those neighborhoods to heat exposure, like those with preexisting conditions such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Adaptive capacity, meanwhile, assesses access to resources like air conditioning needed to mitigate impacts. The plan uses these elements to target the groups that need the most help and provide specific interventions, Stone says.

The city announced this $106 million plan in 2017 after establishing other extreme heat initiatives, including painting 10 million square feet of roofs white, installing light-colored sidewalks, and replacing some sidewalk areas with rain gardens that include a mix of trees, flowers, shrubs, and grasses.

Phoenix has also taken steps to prepare for rising temperatures, including coating more than 71,000 square feet of public roof tops with "cool roof" reflective materials, which has reduced building carbon emissions by an average of nearly 28 metric tons per year. The city's policy now dictates that all newly designed and renovated city buildings must include cool roof coatings, and through a partnership with the Global Cool Cities Alliance and other cities, is researching potential pavement coatings and materials that would mitigate the urban heat island effect.

Last year, Phoenix also established a formal partnership with Arizona State University on three main programs to improve heat preparedness:

- A "heat-ready" framework to measure the "heat readiness" of policies and programs, similar to the "storm-ready" program that is now commonplace in many cities.

- A tool that shows the location of bus stops, shops, and schools to determine the most common route pedestrians will take in vulnerable neighborhoods. That tool will allow planners to create a network of cool corridors in vulnerable neighborhoods by adding shading through trees and structures.

- An official heat mitigation and adaptation plan for the city, with a delivery date of 2021.

A database maintained by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency catalogs other big and small actions made by cities and counties nationwide to tackle the urban heat island effect. Miami-Dade County aims to plant one million trees by the end of this year, with a goal of 30 percent canopy cover, while Minneapolis built a green roof on its central library, cutting energy use by nearly a third. Meanwhile, Boston's Green Building Zoning Code requires projects larger than 50,000 square feet to adhere to the U.S. Green Building Council's LEED certification standards, which aim to address energy efficiency in construction through cool roofs and other measures.

Members of a 5th grade class in Miami plant trees and other greenery around their playground during a 2019 Earth Day event, part of Neat Streets Miami's Million Trees Miami initiative, aimed at achieving a 30 percent tree canopy in Miami-Dade County. Photo courtesy Neat Streets Miami.

Supporting vulnerable populations

An investigation by The Guardian published in December 2019 found that while most of the 30 large cities studied had some type of written extreme-heat plan, only 10 specifically mention vulnerable populations. In low-income communities and majority-minority neighborhoods across the country, a common theme is a lack of a tree canopy. In Louisville, Kentucky, for instance, higher-income parts of the city can have up to twice the number of trees as lower-income neighborhoods.

Phoenix is working to improve infrastructure and resources for vulnerable residents by partnering with the Nature Conservancy, Arizona State University, the Maricopa County Department of Public Health, and community-based organizations to develop neighborhood-specific heat action plans. Edison-Eastlake, a Latinx-majority area where the average annual heat-associated death rate is 20 times the county overall, is one such area.

Between the 1930s and 1950s, the neighborhood was subject to redlining, which largely prevented residents from purchasing property; now, only 16 percent own their own homes, while the median household income sits at $10,708. But a recent $30 million federal grant to rebuild old public housing in the area has helped kick-start revitalization efforts, including addressing extreme heat.

The Phoenix neighborhood of Edison-Eastlake, where the average annual heat-related death rate is 20 times higher than the rest of Maricopa County. Photo courtesy Ash Ponders.

The city is working with residents to learn about the specific challenges they face during extreme weather events. "I ride the bus and sometimes I go to the bus stop and it is really hot," one community participant said. "My apartment, it's also really hot in there ... I have to go to bus stations and there is no shade structure. There is nothing. There are no trees along the way ... I wish that there were more trees where I live ... because there is nothing."

Along with a lack of shade on walking routes, bus stops, and at vacant lots due to very low tree coverage, residents pointed to a lack of access to drinking water, services, and amenities for people with disabilities, the elderly, and households struggling to pay high electricity bills. Residents have called for more trees, cooler materials for sidewalks, misters at bus stations, later hours at community pools, and sprinklers in the neighborhoods.

On the other side of the country in Philadelphia, the city has worked with residents to address their immediate and long-term needs through the 2019 Beat the Heat project. The Hunting Park neighborhood has an aging housing stock with dark roof tops, less green space, more paved areas than some other parts of the city, and shaded tree canopy in only nine percent of the area — compared to 48 percent in wealthy neighborhoods like Chestnut Hill.

"The heat can be very ridiculous sometimes," Vernetta Santos, a block captain, told the city in its Beat the Heat report. "It is not good for me or my kids, especially because we have asthma. We can't even sit outside for long periods of time because it gets too hot and there are not too many places where there is shade unless we go to the park. The heat has a bad impact because not everyone can afford to buy air conditioners or fans. I would like to see more help with air conditioning for people who desperately need it."

After collecting input from residents, Beat the Heat led to a series of recommendations, including to improve access to efficient air conditioning units, offer cool roof coatings and insulation, and develop a system to check in on vulnerable residents.

New York City has also launched its own engagement-driven program, Be a Buddy NYC, which fosters a buddy system between social services, community organizations, and volunteers with vulnerable New Yorkers. The community partners that implemented this program serve a population of approximately 1,500 heat-vulnerable residents and have a volunteer base trained to understand heat risk and check in with residents, including remotely. These investments have been focused on New York City's most heat-vulnerable neighborhoods, including majority-minority neighborhoods of the South Bronx, East Harlem, and Central Brooklyn — areas that have also been hit hardest by COVID-19.

Members of the Roof Coatings Manufacturers Association cover roofs with rubberized white paint in Philadelphia to help keep buildings cooler. The city's Beat the Heat program identified cool roofs as one tool against the heat island effect. Photo courtesy Energy Coordinating Agency Philadelphia.

The pandemic's impact

As long-range planning for extreme heat remains a serious concern, the coronavirus is adding its own set of challenges. Philadelphia had been working with Hunting Park community leaders to launch a heat relief network, including cooling centers, but COVID-19 put that plan on hold. Back-up plans, including a system to check on vulnerable residents, were being formulated at the time of publication.

For some residents who lack working air conditioning or can't afford it, leaving the home is the only way to get heat relief — meaning that this summer, any "stay inside" orders could prove dangerous, says Melissa Guardaro, a research fellow at Arizona State University's School of Sustainability. That's why New York City has pivoted to focus on keeping vulnerable residents safe at home. The city has created a $55 million plan to provide more than 74,000 free air conditioners to low-income seniors, while the New York State Public Service Commission has approved $70 million in utilities aid for about 440,000 families from June to October.

Across the country, in areas where social distancing requirements of any kind have remained in place, residents have been unable to lean on the places they typically use to escape the heat, like pools, libraries, or malls. Local governments that operate cooling centers will have to determine whether they can safely open them; the U.S. Centers for Disease Control has released new guidelines for cooling centers, including social distancing and sanitation recommendations.

"Even in the midst of this COVID crisis, climate impacts are going to continue," Rachel Cleetus says. "There are going to be places that are going to have to contend with these risks simultaneously."

Amy Sherman is a Fort Lauderdale-based staff writer for PolitiFact and a freelance writer for national and state publications.

Policies That Help Beat the Heat

A cooling center in a New York Public Library during a 2019 heatwave in the eastern U.S. Photo by Gabriela Bhaskar/The New York Times.

APA's Hazard Mitigation Policy Guide, first adopted in 2014, has been updated with a variety of new recommendations to reevaluate the ways we mitigate, adapt to, and recover from natural and man-made disasters. Here are six ways planners can help federal, state, local, regional, and tribal governments prepare for extreme heat:

PRODUCE PLANS that prepare for and manage the impacts of extreme weather. Be sure to account for local and regional emergency health care providers.

ENCOURAGE LANDSCAPE AND HARDSCAPE designs and building placements and types that reduce the urban heat island effect.

PROVIDE ADEQUATE SHELTER FACILITIES with properly trained managers that can address the needs of at-risk populations, including the elderly, unhoused people, and residents with disabilities.

CREATE ADEQUATE LOCAL MONITORING systems for house-bound at-risk populations.

SUPPORT STATE AND LOCAL AGENCIES developing working relationships with utilities to make sure they are not shut off due to unpaid bills during extreme heat.

REQUIRE HEATING AND COOLING SYSTEMS in publicly supported housing that are designed for existing and projected climate conditions.