Planning December 2020

Transit in Crisis

The pandemic has dealt public transportation its biggest challenge in decades — and it isn’t over yet.

By Daniel C. Vock

The first indication that Columbus, Ohio, could face serious ramifications from the coronavirus came in early March, when state and local officials drastically scaled back the Arnold Sports Festival, an event organized by Arnold Schwarzenegger that was expected to draw a quarter of a million people from around the world. Soon after came the dire warnings from public health officials about the disease's spread. Gov. Mike DeWine even postponed the state's planned primary election.

Within a few weeks, the Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA) implemented its own drastic measures, including suspending all fares, requiring passengers to board buses through the rear door, and limiting the number of people allowed on each bus to 20. COTA also reduced hours to provide flexibility for caretakers on staff and divided much of its workforce into two cohorts, so an outbreak in one would have limited impact on the other.

Kimberly Sharp, AICP, a planner and COTA's senior director of development, says top agency officials from multiple departments convened every morning at 8 a.m. to review data and feedback from businesses, nonprofits, Ohio State University, and local schools to see how to adjust policies.

"There were some lines which immediately saw huge reductions in ridership or no ridership, because of the governor's stay-at-home order," Sharp says, so they reallocated resources to support routes still seeing significant use. The agency was also careful to preserve lines depended on by essential workers, or that served food pantries and schools where meals were being distributed. Still, COTA went from handling about 60,000 trips a day in March to just 16,000 by May.

A lone traveler waits at a Boston subway station in March, when state and local governments began issuing emergency closures and mandates due to COVID-19. Photo by Katherine Taylor/The New York Times.

A Vital Bus-Meal Connection

While some bus routes were reduced due to low usage, COTA made sure to maintain lines that provided access to free lunches at Columbus-area schools.

Courtesy COTA.

Nationwide, the story has been largely the same. The pandemic is the biggest crisis in decades to face a public transit industry that was already struggling to retain riders. Second-quarter ridership for subways, light rail, and commuter railroads plummeted by more than 85 percent by more than 85 percent compared with the year before, according to the American Public Transportation Association (APTA). The number of bus passengers fell by two-thirds.

But ridership isn't the only transit problem. Major losses in fare revenue go hand in hand with fewer passengers, of course, especially in areas like Columbus that temporarily canceled fares; compared to the same month a year before, fare revenue in April dropped by 86 percent. Transit agencies are also dealing with slashed budgets, limited federal aid, and even tax subsidies at a time when costs have increased. Some have faced staffing shortages due to in-person schooling, loss of childcare, and the virus itself.

Which tees up the biggest challenge: keeping employees and the passengers they do have safe. Initial fears of massive COVID-19 spread on transit were mostly overblown, and agencies are making a point of emphasizing employee health and convincing the public it's OK to use buses and trains, but a full recovery is months, if not years, away.

Passengers will return, though, promises Steven Higashide, the director of research for Transit Center, a New York City think tank. People started taking transit quickly after the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong and Thailand, he says, and after the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington in 2001, too.

"Ridership rebounded within weeks or months, once that source of fear had been taken away," he says. "So the question is not so much: will people be scared of transit forever? History suggests that they will not."

Instead, he says, cities and agencies are facing a much bigger question: what kind of public transit system will the majority of passengers find when they're ready to ride again?

To help keep employees healthy, COTA has distributed masks, gloves, and cleaning solution. The agency has also spent more than $1.6 million in federal funds on plastic barriers that protect drivers. Photo courtesy COTA.

Many agencies fear a financial freefall

COTA has fared far better than most of its peers: By the end of September, ridership in Columbus had rebounded to close to 50 percent of pre-pandemic levels, and the agency's finances have been cushioned by revenue from a regional sales tax.

Other agencies, however, continue to face more harrowing prospects. In Los Angeles, where ridership is still around half of its pre-COVID levels, the directors of the county's Metropolitan Transportation Authority voted to reduce the agency's annual budget by $1.2 billion and service by 20 percent. That would mean reduced funding for new rail lines and planning work. LA Mayor Eric Garcetti, who chairs the transit agency's board, calls it "the most challenging budget year we've ever been through."

The Maryland Transit Administration, meanwhile, initially called for eliminating 25 bus lines in the Baltimore area and reducing service on 12 more, as part of their own effort to trim costs by 20 percent, but the plan caused an uproar.

"Make no mistake about it: This decision will disproportionately impact our poor, Black and Brown residents, especially those living in historically disinvested neighborhoods," Baltimore's mayor, city council president, and the county executives of three counties in the region said in a statement at the time. "Particularly during a public health emergency that continues to have devastating impacts, we should not seek to balance the budget on the backs of the most vulnerable." The MTA decided instead to cut commuter rail and longer-distance bus routes.

The financial strain on transit agencies comes both from lost income — like drops in fare revenue or decreases in local sales tax contributions — and increased costs. Agencies must often run additional buses on routes to make sure vehicles aren't too crowded for physical distancing, which also requires more drivers and more maintenance staff. There's also the issue of heightened safety standards. In Columbus, COTA spokesperson Jeff Pullin says every bus is sanitized three to five times a day, and workers cover all surfaces of the vehicles with an antimicrobial solution to reduce the chances of transmission. The agency also spent $1.6 million in federal money to install barriers to protect drivers, Pullin says, which comes on top of the masks, gloves, and cleaning solution COTA is buying employees.

In the early days of the pandemic, the CARES Act, which President Donald Trump signed in late March, included $25 billion to shore up public transportation. According to APTA, that money prevented major layoffs at most transit agencies. But by September, the Federal Transit Authority had already doled out 92 percent of all transit relief available — and partisan disagreements were preventing Congress from passing any major followup legislation.

As of early November, no new aid had been approved. But with six of every 10 transit agencies planning for layoffs, furloughs, and service cuts in the new year, APTA says transit agencies need another $32 billion from Congress. Otherwise, the impacts could be devastating: The Transit Center in September modeled a scenario in which transit providers in 10 metro areas had to cut back half of their peak service and 30 percent of non-peak service. The result? More than three million households and 1.4 million jobs without frequent transit access.

Indeed, New York officials are warning that its system — the largest by far in the U.S. — will need to reduce service by as much as 40 percent if no additional federal relief is provided. That would be a monumental blow across the board, but especially for communities that have long seen disinvestment and have already suffered at disproportionate rates from the virus.

"Transportation cuts would take out the legs from under cities engaged in a life-or-death struggle with the virus," the Transit Center said in a statement. "Black and Hispanic residents would be hardest-hit. Second- and third-shift workers would lose an affordable way to commute, and households without vehicles would have an even harder time meeting everyday needs."

If no additional federal relief is provided to transit agencies over the course of the pandemic, New York City might need to cut its service by 40 percent. Photo by Chang W. Lee/The New York Times.

Transit suffers from preexisting conditions

While COVID-19 brings its own challenges, it's also compounding difficulties the industry has struggled to address for years — and forcing transit agencies to rethink business as usual.

The prolonged financial stress could undermine industry-wide efforts to reduce the backlog of repairs that have piled up over the decades. Getting transit systems to a "state of good repair" would take more than $89 billion, according to the Federal Transit Administration. Neglected infrastructure has caused huge problems for transit systems in places like Boston, the San Francisco Bay area, New York City, and Washington, D.C. Those systems have all put a major emphasis on improving safety and efficiency for at least the last five years, but a shortage of cash could hinder those efforts.

"In the first few months of the pandemic, many agencies like [Washington Metro] here in D.C. were able to accelerate their capital projects and actually get work done quicker, as a result of not having, frankly, as many riders," says Paul Skoutelas, the CEO of APTA. "But what is happening as this pandemic has stretched out longer is that agencies are having to reorganize their budgets and take from their capital budgets in order to make sure their operations are afloat. So it is a real concern that agencies will defer projects or start to cancel them outright."

There's also the existing issue of passenger retention, especially on bus routes. The emergence of ride-hailing apps, the movement of low-income people from urban areas to suburban areas, and rising car ownership have all played a role. Those factors aren't likely to go away, even after coronavirus concerns ease.

By the Numbers

85% drop in second-quarter ridership for subways, light rail, and commuter railroads compared with last year.

67% decrease in bus ridership compared with the same quarter last year.

$32 billion in federal emergency support is needed beyond what was provided in the CARES Act, transit authorities say.

45% of the U.S. had no access to public transportation before the pandemic.

60% or more of all transit agencies expect to make service cuts if no additional emergency funds are provided.

$89 billion in transit system repairs have been put off for decades across the U.S.

92% of the $25 billion provided for emergency transit funding under the CARES Act, which was signed into law in March, had already been awarded by September.

90% drop in ridership on Metra, the Chicago region's commuter rail line that connects the distant suburbs to the city's downtown area, compared with the same time last year.

80% of America's large transit agencies are considering delaying, deferring, or canceling capital projects to help close budget gaps.

Sources: American Public Transportation Association, American Public Transit Association, Federal Transit Administration, METRA

Public transit advocates say now is the time to reassess how we're addressing those problems. Kate Lowe, a professor of urban planning and policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, says the stresses of the pandemic should influence leaders to think more comprehensively about how bus and rail service could better serve more populations, especially low-income residents.

Across the country, the people who have depended on transit service during the pandemic have been largely low-income, Black, Latinx, Hispanic, and/or women, according to an April study by the makers of the Transit app. "We've seen a remarkable 'white flight' from public transit," the company, which provides bus arrival times and other transit information, says about their pandemic user makeup. "Among whites, public transit ridership has dropped by half. Black and Latino riders now make up the majority of Transit's users."

In Boston, the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority went through a lengthy review of how different service cuts would impact different types of riders. They found that more than a third of the riders on its Green Line came from households with no cars, compared to just one percent on a commuter rail line to several South Shore communities. LA Metro, meanwhile, is exploring the possibility of eliminating fares for all train and bus passengers.

In San Francisco, the city's Metropolitan Transportation Agency shut down its rail lines, which cater to office workers commuting downtown, and moved to an all-bus system to better serve hospitals and neighborhood shopping areas where essential workers need to go. Similarly, advocates are pushing for the Chicago area's Metra commuter rail agency, which runs lines between the city and distant suburbs, to reallocate money to the Chicago Transit Authority for buses and subways.

"This gives planners and transit agencies further impetus to think beyond the commute trip," which tends to favor white-collar workers and therefore has serious equity implications, Lowe says. "To make transit viable, we need to make [it] useful for people who live in areas where transit is efficient."

The San Francisco Metropolitan Transportation Agency shut down its commuter-focused rail lines and moved to an all-bus system to better serve hospitals and shopping areas where essential workers needed to go. Photo by Christie Hemm Klok/The New York Times.

Advocates say it's time to switch tracks

Decision makers need to develop new ways of supporting transit that don't punish agencies for public policy choices made by others, says Lowe, especially those steering potential passengers toward private vehicles. That includes the federal government, which in the last several decades has spent far less money on transit than it has on building or expanding highways.

More locally, policy makers have often allowed or even encouraged high-end developments near transit stops, which tend to attract high earners who own their own cars. Lowe points too to her work with focus groups in the Chicago area, which shows that fears of violence and police discrimination also contribute to the decision to move from using transit to a car.

In its initial rescue package, Congress allowed transit agencies to use relief funds to pay for operational expenses. That's a departure from the federal government's traditional approach, Lowe says, which subsidizes construction and other capital expenses while forcing agencies to look elsewhere for day-to-day cost coverage.

If Congress changed that approach permanently, "it would be a lifeline for big city transit operators," Lowe says. "If the federal government loosens up its restrictions, we can focus on those who most rely on and use transit, and have a trickle-up [approach], rather than a trickle-down, dream big, overbuild strategy that has been the paradigm."

Christof Spieler, AICP, an engineer, planner, and the author of Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of U.S. Transit stresses that the responsibility for maintaining robust transit systems goes far beyond the agencies themselves. State and local governments could also support public transportation.

"I worry sometimes that we talk about those cuts as if they're inevitable," he says. "They are policy decisions, but often agency staff aren't the ones who get input into those policy decisions. They're the ones who are told: Here's how much you need to cut."

In Columbus, the pandemic has already led to changes in how COTA operates, like a new bus-on-demand service to the airport and other destinations in northeast Franklin County. But the agency is also still working on ambitious, long-term projects to prepare for decades of growth in the region. COVID-19 can't put a halt to that.

"Not only are we working to recover from the pandemic and reimagine our system in the middle of the pandemic, but we're also up to 1.5 million more people who are anticipated to be in Columbus by 2050," says Pullin, the COTA spokesperson.

"We can't wait until the pandemic is over," he adds. "We have to prepare for the future at the same time."

Daniel Vock is a public policy reporter based in Washington, D.C. He is also the author of the States of Crisis newsletter.

The State of Transit Today (And Maybe Tomorrow, Too)

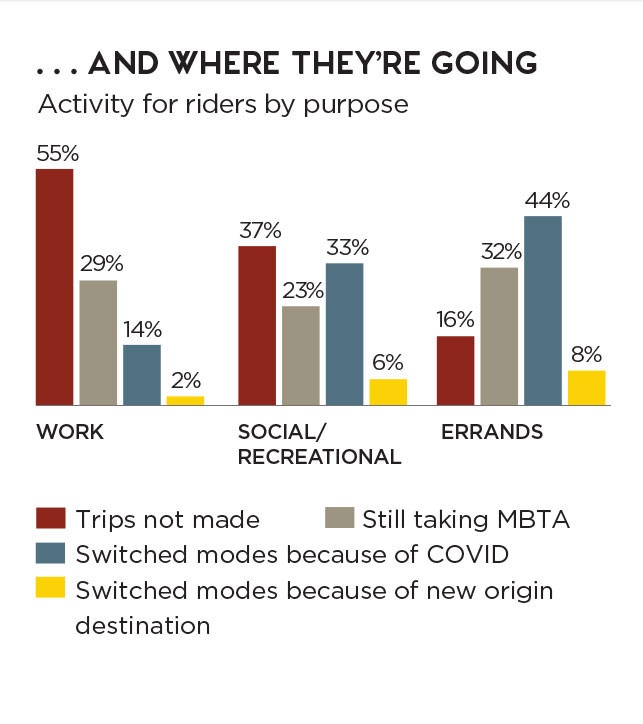

The Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority (MBTA) collected rider data via monthly surveys to help determine who was using transit and where they were taking it during the pandemic. The results show some significant changes — and if telecommuting patterns continue, could signal the need for more long-term service adjustments.

Source: MBTA Customer and Employee Survey Results (10-14-20)

Source: MBTA Customer and Employee Survey Results (10-14-20)

With many white-collar employees telecommuting indefinitely, ridership will likely struggle to bounce back to previous levels. To better cover budget gaps and keep transit viable in the meantime, MBTA is taking a critical eye to its services: During a September meeting, for example, the agency discussed cutting routes that serve areas with mostly remote workers and shifting resources to low-income riders.