Planning June 2020

Transportation

As Mobility Patterns Change, Cities Shift Gears

Around the world, more cyclists are hitting the streets — and cities are making room for them.

By Dorottya Miketa, AICP, PP, and Po Sun, AICP

Not long after its first reported case of COVID-19 in early March, the New York City region became the world epicenter of the pandemic, prompting city and state leaders to implement stringent social distancing measures. Mayor Bill de Blasio urged New Yorkers to avoid mass transit to help limit the risk of transmission and protect essential workers who rely on it.

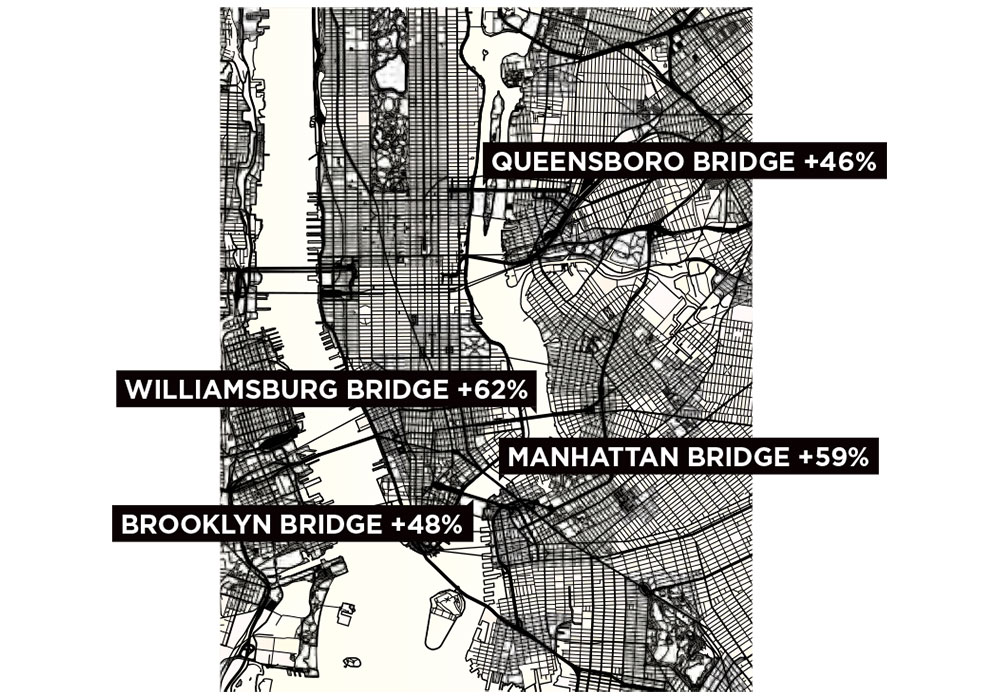

So far, residents have followed these instructions en masse. In early March alone, the city's bike-share system, Citi Bike, had handled 517,768 rides, a 67 percent spike from the same period last year. The four major East River bridges connecting Manhattan with Brooklyn and Queens saw up to a 62 percent increase in cyclists compared to last March. And by April 8, when the city's reported cases were nearing 10,000, subway use had dropped by a whopping 92 percent.

Across the globe, major city streets are seeing fewer private vehicles and more cyclists, prompting a pressing need to reimagine our car-centric thoroughfares.

Berlin is transforming a number of vehicle lanes into bike lanes to promote cycling during the coronavirus pandemic. While this one on the thoroughfare Kottbusser Damm is temporary, the city plans to install a permanent version in September. Photo by J'rg Carstensen/Picture-Alliance/DPA/AP Images.

Bogotá residents take advantage of a temporary bike lane along busy 80 Street Avenue, one of many pop-ups added to the city's 340 miles of existing bike lanes. Photo by Gabriel Leonardo Guerrero Bermudez/iStock Editorial.

Reclaiming the streets

With 340 miles of bike lanes, Bogotá, Colombia, has long cultivated a strong pro-cycling culture. Every Sunday and on holidays, miles of the streets are temporarily closed to vehicles for Ciclovia, the open-streets program run by the local transportation department since 1974. It's no surprise, then, that Bogotá was one of the first cities to turn to transportation planning to fight the pandemic.

Mayor Claudia Lopez Hernandez has urged residents to eschew the city's overcrowded bus rapid transit system in favor of bikes for necessary trips. On March 17, as Colombia hit 75 reported COVID-19 cases, the city installed 13 miles of temporary bike lanes overnight by offsetting a vehicle lane with traffic cones. Within days, 47 total miles were in place for use from 6 a.m. through 7:30 p.m. daily for the remainder of the crisis.

"The bike lanes were implemented partly due to the red air quality alert, [which] helped reduce the use of public transport by 40 percent in a week," says Amalia Toro-Restrepo, an urban planner who lives in Bogotá, noting that air pollution has been linked to increased COVID-19 death rates.

Temporary bike lanes are showing up in other cities too. Berlin's district of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg has installed pop-ups and restriped existing lanes to promote social distancing, especially necessary at intersections, where restricted space left cyclists congregating while waiting for the light to change. And in New York City, where the rise in ridership was accompanied by a 43 percent increase in cycling injuries, Mayor de Blasio announced the addition of temporary protected lanes on two busy corridors: Smith Street in Brooklyn and Second Avenue in Manhattan.

In addition to temporary bike lanes, cities have also enacted policies of various magnitudes to reclaim streets for both bicyclists and pedestrians. In Brookline, near Boston, the transportation board voted to temporarily remove and repurpose parking lanes along four high-density streets to give essential workers sufficient space to socially distance while commuting to and from work.

Some cities have closed streets entirely to cars. Most notably, Oakland has enacted an extensive Slow Streets program to support pedestrians, cyclists, and people who use wheelchairs by creating additional space for physical distancing. All existing and proposed Neighborhood Bike Routes, which account for nearly 10 percent of all Oakland streets, have been closed to through traffic as part of the program.

"In this unprecedented moment we must do everything we can to ensure the safety and well-being of all families across our city," Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf said in a press release. "Closing roads means opening up our city. It gives our residents the opportunity to get outside and walk, bicycle, or run through their neighborhoods and get around in a safer way."

St. Paul and Minneapolis have followed suit in Minnesota, banning motor vehicles from significant portions of roadways along parks and lakes while shelter-in-place orders are in effect. Minneapolis also announced the new program Stay Healthy Streets, which connects residential areas to trails and parks via approximately 15 miles of pedestrian and cycling routes, some of which will be closed to vehicle traffic.

New York City's Biking Boom

As of March 10, East River bridges saw a massive ridership increase from 2019's select daily average.

Map by Huoshu/Digitalvision Vectors.

Incentives and outreach

Bike-share programs have played a critical part in changing transportation patterns. In Berlin, 30-minute rides on the city's bike share, nextbike, were made free starting in mid-March through a partnership with the Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport, and Climate Protection.

Similar programs are being implemented in the U.S. Lyft, the largest bike-share operator in North America, launched the Citi Bike Critical Workforce Membership Program in New York City in conjunction with the mayor's office and the NYCDOT in late March. The program initially provided a free month, later expanded to a free year, of membership for first responders, health-care workers, and the transit workforce. Citi Bike has also prioritized valet resources at stations adjacent to hospitals that have seen significant ridership increases.

Lyft also introduced similar free and reduced fare programs for essential workers in Boston and Chicago, where trips for other riders have also been discounted, including a 50 percent decrease of annual membership costs.

In France, the government is dedicating $21.7 million to boost bike use. Private bike repairs will be subsidized at more than 3,000 repair shops, while remaining funds will be dedicated to cycling education. The program is an attempt to encourage use now and once restrictions are lifted, Minister for Ecological Transition Élizabeth Borne told BBC World News, pointing to the fact that 60 percent of trips there are three miles or less.

Oakland's Slow Streets program launched during the pandemic, opening up 16 miles (and counting) to bicyclists and pedestrians. Photo by Sergio Ruiz.

Moving forward

While overnight bike lanes and reduced bike share fares have been billed as temporary, cycling culture and infrastructure could see lasting impacts in a post-COVID-19 world, whenever that may come.

This isn't the first time cities have relied on bicycling as an emergency transportation option. During the 1973 OPEC oil embargo, the Netherlands government rolled out the car-free Sundays that paved the way for Dutch municipalities to implement more cycling-friendly policies. Cycling experiences now, along with the appropriate infrastructure to support them, could convert new users into long-time riders.

"A new generation of cyclists would benefit if we had the means to learn from this moment," says Chelsea Yamada, the Manhattan Organizer at Transportation Alternatives in New York City.

Dorottya Miketa, AICP, PP, a transportation planner, and Po Sun, AICP, a senior transportation planner, work at Sam Schwartz in New York City.