Planning November 2020

The Call for a New Fiscal Architecture

The financial structure of state and local governments has been bashed by COVID-19, and we have a once-in-a-century opportunity to reinvent how we pay for the peerless cities we plan.

By Michael A. Pagano

More than six months after the partial closing of the economy because of the coronavirus, as of mid-September states and localities had estimated their fiscal losses and the impact of the falling economy at over $780 billion. Moody's Analytics placed the loss at $500 billion for fiscal years 2020–22. Either figure illustrates the magnitude of the impact COVID-19 is having on state and local fiscal systems, which could have the ripple effect of reducing GDP by three percent and erasing four million state and local jobs. And things continue to get worse.

In times of disaster, it's the great hope in the sky that the federal government will step in and help. But thus far, that has turned out to be wishful thinking. Congress failed to approve a rescue plan, the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions Act, or the HEROES Act, that would have supported state and local governments before summer recess ended the debate. What the House and Senate will do next is still a giant question mark, but in the interim, it will be very painful as states and local governments wait for the money they hope will arrive someday.

The financial challenges now facing states and localities are — like so much about the pandemic — unprecedented. There is no historical marker to gauge the rate of fiscal deterioration of many of the nation's cities and states, which makes developing solutions extremely difficult. The rapid lockdown of the economy beginning in March not only closed markets, but it also dried up the stream of resources that fund our police and fire departments, K–12 education, parks and recreation, courts and prisons, roads and bridges — indeed, all public services, which are provided through a combination of taxes, fees, transfers from other levels of government, and, in the case of capital projects, the issuance of debt.

COVID-19's sudden closure of the economy, followed by fiscal free fall, places public services on the precipice. How to climb back to more secure turf? The answer is uncertain, but it's clear the search for solutions must be on planning's to-do list. To start, planners must learn about the financial underpinnings, or "fiscal architecture," of their communities and regions. Only then can we plan for an inclusive, resilient, livable society by designing an equitable, efficient, and effective system of paying for public services. But first, let's understand what challenges COVID-19 brings, and the role of planners.

Illustration by Chris Gash.

Struggling cities, slow rebound

Budgets are in absolute disarray right now, but there are some mitigating circumstances. Fortunately, city (and state) reserves were at an all-time high (Illinois and Chicago, where I reside, to the contrary), which will cushion some of the blow. The median value of reserves for states in 2019 was almost 14 percent of expenditures, and for cities, it was estimated at nearly 30 percent of general fund expenditures, according to the National Association of State Budget Officers, Fiscal Survey of the States, 2020, and the National League of Cities' annual City Fiscal Conditions survey, respectively. Drawing down these reserves was among the very first fiscal actions taken, but budget stabilization funds, reserves, and "rainy day" funds are finite, and certainly aren't being replenished now.

Service levels will need to be rebalanced too, as will public safety (the defund police movement is raising this question). Renter eviction ramifications will force governments (and nonprofits) into the unenviable position of providing for a larger indigent population as their coffers are drained.

Data on cities' general funds over the last four decades indicate that once a recession ends and revenues begin to flow back into city coffers, rebuilding the cities' revenue base is slow. Even if the pandemic ceases tomorrow, the recovery will take years.

The general funds of cities returned to their pre-Great Recession levels in constant dollar terms only recently, in 2019. If that rebuilding of general funds took a decade, I can't imagine that the COVID-19 rebound will be much faster. Some estimates put the nation's economic rebound at four years (through 2024), which, if accurate and no other changes to cities' fiscal powers are made, might mean that cities' funds might have to wait for a full rebound until 2030.

That's insufferably long if we don't have adequate resources to shape and create strong neighborhoods and cities. That's why we must begin immediately to align cities' fiscal levers with their underlying economies to capture those resources today rather than a decade from now.

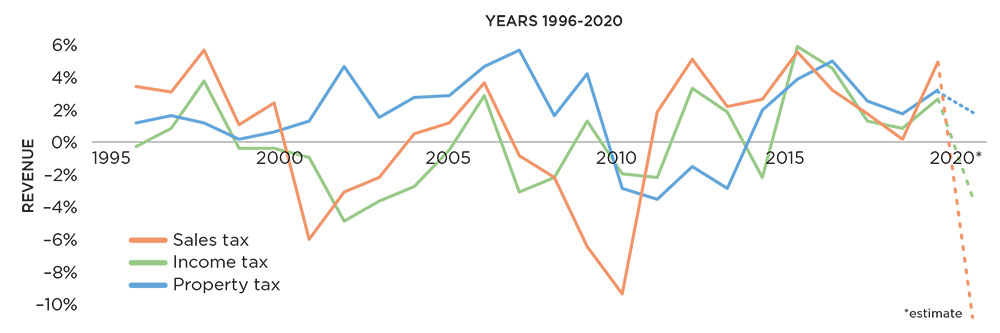

Comparative Revenue Trends During Recent Recessions

Revenue recovery varies, but the most recent recession (2007) shows a recovery time of 13 years. If that trend continues, the COVID recovery might not come until 2030.

Source: Christiana McFarland and Michael Pagano, City Fiscal Conditions 2020.

Cities' fiscal profiles vary

A city's fiscal architecture, or the alignment between the economic base and the tax/fee authority of a city, will influence how quickly cities rebound. What works in one place may not work in another because city taxing authority varies across the political landscape. In short, there's no silver bullet and no "one-size-fits-all" fix.

In large part, this is due to the fact that cities' access to general tax revenue varies considerably. For some cities, such as Boston, Atlanta, and Minneapolis, the primary general tax source is the property tax, while for others, such as Oklahoma City, Little Rock, Arkansas, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, sales tax is the largest tax source. And in a few cities, such as Cleveland; St. Louis; and Louisville, Kentucky, the income or wage tax generates a large amount of revenue. Given this diversity of revenue reliance, the roots of many cities' current fiscal woes lie in their relative dependency on two very elastic taxes — sales taxes and income taxes — which respond immediately to economic changes. Both have witnessed a dramatic reduction in revenues basically overnight. For example, Seattle; Denver; Anaheim, California; and Chicago — cities that collect a sales tax — estimated revenue losses of 6–15 percent, as did Detroit and Washington, D.C., which collect an income tax.

Traditional literature indicates that property tax receipts are the most stable of the major source of city revenues. But even they aren't immune to the vicissitudes of economic collapse. To the extent the real estate market suffers, property tax receipts will be hard hit next year. The fiscal impact of COVID-19 will be rolling through the nation as some cities are most immediately affected in the first few months while others will experience the impact next year after their property tax assessments are estimated.

I anticipate, then, that bedroom communities that depend on property taxes as the main revenue source may be currently experiencing only minor reductions in revenue, but a year from now, assuming the economy negatively affects the salaries, income, and employment of bedroom communities, property values will drop and tax receipts will begin to dip.

Year-Over-Year Change in Receipts

The abrupt closing of the economy is reflected in a rapid drop in sales and income tax receipts. Property tax receipts are likely to drop when next year's assessments are calculated.

Source: Christiana McFarland and Michael Pagano, City Fiscal Conditions 2020.

Incremental change is not enough

Fiscal policy behavior, much like human behavior, changes slowly and incrementally year to year — until a catastrophic event shocks the system and encourages more than just marginal adjustments.

The pandemic is one of those shocks, as is the Black Lives Matter movement, which accelerated after George Floyd's killing. My research has found that most cities' fiscal structures — what I like to refer to as their "fiscal architecture" — are not well linked to either their underlying economy (that is, the linkage or alignment between the economic base and its fiscal structure) or with the taxpayers' ability to pay or with beneficiaries of public services. And while that mismatch may eventually come to light and cause problems over time, major disruptions can suddenly expose the disparities and inequities in the current fiscal system.

Cities' fiscal architectures are a relic of the past. They were designed decades ago and only change at the margins. Hence, everyone agrees that the sales tax base is too narrow, the property tax — which at one time was connected to wealth — is not necessarily fair, and the few places with income/wage taxes are often regressive. So, when the fiscal architecture has been bashed by the pandemic and, as of this writing, the likelihood of federal relief wanes, this could be the most opportunistic time in a century for cities to self-examine.

Minor adjustments to tax rates or tax bases, slight reductions in tax and expenditure limitations, and a small uptick in state aid should not be part of the self-examination, for these are small, gradual adjustments that are not designed to address fundamental problems in the design of a city's fiscal architecture. It's time for massive change, not incremental thinking!

Planners are employed to help the city and citizens envision the future, create a better physical place at human scale, and harmonize societal forces in spaces. Often, the work of planners is to adjust and react to changing circumstances, making important, positive, equitable changes to land-use, housing, transportation, and other policies. During times of upheaval, planners have become much more involved in pushing for grander solutions.

Active engagement with city officials and elected leaders is also part of a planner's role and civic responsibility. Successful planning requires a healthy democratic impulse to design a financial future and a fiscal architecture that matches our strategic plans of designing healthy, inclusive, quality neighborhoods and peerless cities. And a massive shock — one that is still reverberating and will not likely abate for years — can or should catalyze seismic shifts in designing a fair, resilient, and efficient fiscal future.

Breaks from tradition are realized during breaks from history. Understanding the current fiscal architecture of your city — and the connection between the city's engines of economic growth and its capacity to secure resources for public purposes — is the first step for planners to take in order to fundamentally reimagine a better, fiscally sustainable, and fairer city future.

Michael Pagano is the dean of the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Planners Take Note

Cities will be forced to rethink core or essential services, and planners will be required to make the case that more planning tools and planners, not fewer, are necessary, despite tighter budgets.

If the fiscal rebound to a new normal from the depth of the current recession is slow, as seems very likely, cities will be forced to rethink core or essential services. It seems intuitively clear that planners dealing with this necessity — which is onerous, at best, to elected officials — will be required to make the case that the clarion call they are answering will require more planning tools and planners, not fewer, despite tighter budgets.

There's a balance question that establishes an unfortunate challenge to planners: proposing innovative solutions incentivizes procrastination and delay. We all know that we should invest continuously in fixed assets and prepare for the 100-year flood. But many leaders and taxpayers have great difficulties analyzing risk effectively. So some have the propensity to hear the phrase 100-year flood as describing something that could occur in a century, while it's just as likely to happen next year.

Planners have a key role to play in helping elected officials, the public, and other stakeholders rethink, visualize, prioritize, and implement fundamental and lasting long-term changes.

We also know that voters control to a large extent how much money cities can spend each year. Yet it's hard to convince taxpayers to pay more for future possibilities especially if it means trading off service levels today. How many voters are thrilled with the notion of cutting back on teachers, firefighters, or even sanitation workers so we can maintain our facilities?

Up until earlier this year, despite a history of economic crises and disruptions caused by nature, pandemics have tended to be considered in the future tense. Governments have not been astute at guessing when the pandemics would happen and investing in advance to address them. We tend to be much more reactive than proactive, and we certainly haven't mastered the ability to weigh future benefits against current costs. We hope against hope that a disaster won't happen on our watch.

City leaders address issues as realists, which often means that plans — even if they have bold visions of the future (think of our carefully drafted 20-year planning documents) — make incremental impacts that, over time it is hoped, will end up making lasting change. A pandemic such as COVID-19, which knows no borders, requires governments to plan together, which is the reason federal agencies and state agencies should coordinate in response to this world-shaking yet unpredicted situation.

A similar circumstance has prevailed for a couple of decades in regard to climate change. Notwithstanding politically oriented debates about the reality of climate change, even those cities and states that believed the warnings 20 years ago didn't expect the thermometer's rise to move upward as quickly as now appears to be the case. Today, absent a federal approach, cities in coastal areas are preparing alone or with their individual states.

Now, possibly more than ever, planners have a key role to play in helping elected officials, the public, and other stakeholders rethink, visualize, prioritize, and implement fundamental and lasting long-term changes that will contribute to building fairer and more resilient communities. Broaden the sales and property tax bases and make them more equitable. Align the economic and fiscal bases of your city. As you and your neighborhoods design a better, more inclusive city, be sure to intentionally connect it to a more equitable and inclusive fiscal architecture.