Jan. 18, 2023

Over the past few years, Americans have faced record-breaking inflation, climbing interest rates, and a general flood of rising costs. But for so many, the bedrock of high living costs is high housing costs.

Rents and home costs have reached stratospheric levels. The nation is 3.79 million units shy of its housing needs, according to advocacy group Up for Growth — a figure rapidly getting worse. Home prices in 98 percent of the nation's metro area rose an average of 8.6 percent, hitting nearly $400,000, per the National Association of Realtors.

Meanwhile, rents spiked 15 percent in just one year, according to the National Low-Income Housing Coalition. In no county in the entire country can a worker on minimum wage working a 40-hour week afford a modest two-bedroom rental home. Harvard's Joint Center for Housing Studies found rental vacancies hit an all-time-low in 2021, with a recent rise in housing development simply unable to meet demand. It's a shortage that curtails growth and limits economic mobility and opportunities for all.

"We're seeing huge, tremendous growth in our area, but we don't have the housing to support that," says Emily Phyllis, AICP, a planner and researcher at One Columbus in Columbus, Ohio. "Being able to really increase the housing supply as well as diversify the housing supply so that we can remain an affordable region for all, that's really primary for us."

The cause of much of that shortage — and, as reformers, YIMBYs, and urbanists point out, much of its solution — lies in zoning policy. The post-WWII housing boom, sparked by gargantuan federal investments in homeownership via the GI Bill and the Federal Housing Authority, new mortgage options, and vast government financing for interstates and highways, paved the way for suburban speculation, seas of single-family starter home developments, and vastly increased housing options and availability (mostly for white, upwardly mobile families).

In recent decades, the pendulum has swung definitively back toward constricting the creation of new homes. Labor and material costs, and especially land use policies, make it harder and more expensive to build. A raft of zoning and building code restrictions — height limits, setbacks, single-family-only zoning, local design review, parking minimums — made it harder and more time-consuming for developers to find suitable land, get approvals, and break ground, driving down the numbers of units built while increasing the cost of having a roof over one's head. Over time, it's made affordability an issue across more and more income levels and communities.

"We're going to have a real shortage of places for people we depend on every day, whether it's teachers, restaurant workers, or other service type jobs," says Rich Hall, AICP, general manager of the Greater Philadelphia Department of Land Use. "They don't have any place to live, or they'll have to have very long commutes. We need well-rounded communities where everyone has a quality place to live."

But new housing advocacy groups, as well as investments and legislation at the federal, state, and local level, are pushing back, seeking to restore supply and demand and catalyze the creation of affordable housing.

The Housing Supply and Affordability Act, which would help cities rework zoning plans and revisit and eliminate restrictions to new construction, was recently put before Congress, while a new YIMBY competitive grant program, which could help encourage communities to eliminate discriminatory land use policies through grant funding, was passed in late 2022. New investments, like the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, would put money toward housing coordination plans to help cities improve the connection between land use, planning, and transportation. These proposals and plans show a renewed energy around zoning and housing at the federal level — and an awareness that the national government can provide the guidance and resources to empower local jurisdictions to enact important changes.

Zoning reform, championed as a key pillar of change, has suddenly become one of the most talked-about policy topics in local government.

"It's something that a lot of people are thinking about as we're dealing with these concurrent crises of housing affordability, racial and economic equity, and opportunity and climate change and sustainability," planner Nolan Gray, research director for California YIMBY and author of Arbitrary Lines, said in a recent episode of the APA podcast. Zoning rules from a century ago, he argues, make it harder for cities to adapt and grow over time to create the new infill housing needed to achieve housing affordability and sustainability objectives.

So how does zoning reform work? Just as there are multiple causes for the calamitous housing crisis, there are also multiple solutions, which often overlap and complement each other. Here are six tactics decision makers at local and state levels are exploring:

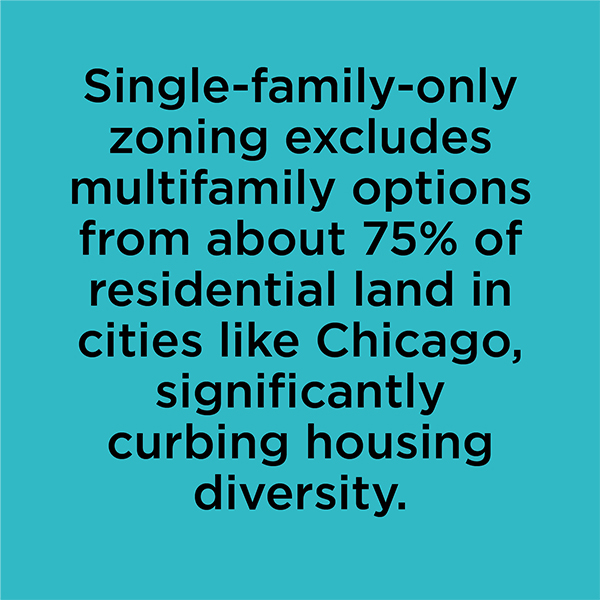

1. Eliminating single-family-only zoning

To build more dense, plentiful housing, cities often need to make room. Zoning rules that only allow single-family residences cover roughly 75 percent of land in American cities, limiting the types of buildings that can be constructed, encouraging sprawl, and discouraging multifamily construction and more efficient mass transit networks. Eliminating these restrictions creates more fertile ground for density and development and increased housing opportunities in amenity-rich neighborhoods near employment.

"If you look at the status quo, which is basically the way that zoning is written right now, it leads to increases of single-family housing development and individual lots being for one individual home, rather than more productive land use and more productive housing policy and economic policy," says Jenny Raitt, executive director of Northern Middlesex Council of Governments, a Massachusetts regional planning agency.

In recent years, challenging and overturning these rules has been a popular method of opening cities up to more affordable units. Minneapolis, which helped pioneer the push in 2018, has been joined by dozens of cities — and even states like Oregon and Maine — that have effectively eliminated single-family-only zoning. It's also been a big boost for smaller municipalities: in Walla Walla, Washington, which recently passed zoning reform and redid its housing plan, the new development climate has already spurred the creation of more multifamily and missing middle housing.

"Change in the physical layout of the city is what can enable the heart and soul of the city to carry on and not depart," says Yorik Stevens-Wajda, AICP, planning director of Everett, Washington.

2. Abolishing parking minimums

America's car-centric culture has become intertwined with our planning, with many municipalities requiring a minimum amount of parking space for residential and commercial structures. It's a reason the U.S. has an estimated two billion parking spots, most of which sit empty and burden the environment, land use, and construction costs. Mandating parking spots robs developers of leasable space and jacks up rental costs; garage parking, which costs about $5,000 per surface space and up to $50,000 per space in multilevel garages, typically adds $142 a month to a household's rent, per UCLA research.

A wave of U.S. cities, including Buffalo, New York, and recently San Jose, California, have pushed forward parking reform in recent years, unlocking new development potential and cutting the cost of new construction. After passing such laws in 2021, Seattle and Buffalo developers built more mixed-use projects; in San Diego, the number of affordable housing proposals rose fivefold after parking space requirements were eased. It's a boon for small cities, too: Fayetteville, Arkansas, and Sandpoint, Idaho, reformed parking rules and found it encouraged new developments and helped create opportunities for new housing and small businesses.

3. Promoting missing middle housing

While many zoning reform provisions open up the universe of possibilities for builders, some municipalities and local governments are going a step further to encourage the creation of certain building types. So-called missing middle housing, a term coined in 2010 by Daniel Parolek, principal and CEO of Opticos Design, consists of multifamily structures of just a handful of floors that offer minimal density and more affordability. In recent decades, they've been hard to build, caught between single-family-only neighborhoods and the economic realities of multifamily construction, where taller and denser are more economically feasible.

Numerous changes to zoning and building codes can encourage more of these kinds of projects: Reducing minimum lot sizes encourages smaller, multistory buildings. Tweaking rules to allow multiple, smaller units within a larger structure improves density. Eliminating zoning restrictions and parking minimums means lower costs for builders. And these are often the kinds of historic, widely admired building types that form the backbone of popular neighborhoods — an easy case to make to the public.

"When you put it in real terms that people understand, when you can point to that four-plex that already exists in the community and say, 'Hey, you know, would it be so bad if we had a few more of these? Then I think it starts to click," says Gray, "People start to get it."

Oxford, Mississippi, embarked on a comprehensive rework of its land use plan in 2017, which planner Ben Requet says included a bedroom-per-acre calculation that incentivized builders to build different kinds of housing. It's already led to more vibrant communities in the southern college town.

"Zoning reform has already started to show significant advances and creativity in our housing supply in Oxford," he says. "We're starting to see more density that's applied in new developments that provide more options and opportunities for not only our student population, but our older populations and even young families."

4. Allowing ADUs

It's hard to radically change the geography and concentration of American housing in single-family only neighborhoods. Accessory dwelling units, or ADUs, seek to work within the system, so to speak, making it legal, quick, and affordable for property owners to add an additional back-yard unit. Early legislation faced pushback from local governments, so states have steadfastly revisited the issue, refining regulations to make permitting more streamlined.

This new push for more ADUs, which has been successful in states like Vermont and New Hampshire, has been especially robust along the West Coast. California alone has seen roughly 60,000 ADUs permitted since 2016 as more state laws and regulations meant to champion backyard building have been passed.

"Accessory dwelling units have quietly been a huge planning reform success story," says Gray. "We've made it to where more homeowners can add additional units in their backyard or in their unused attics or unused basements. These are units that just wouldn't otherwise have existed, units that are making even some of our most exclusionary, high-cost jurisdictions a little bit more affordable and a little bit more diverse and accessible."

5. Zoning for adaptive reuse

The easiest, and sometimes cheapest, housing to construct is one that's already finished. Promoting adaptive reuse and the transformation of existing building stock into new housing has long been a tool planners have used to revitalize neighborhoods. In New York City, for example, conversions remade Chelsea and created a live-work-play neighborhood in Lower Manhattan.

But there are so many other great examples of taking old warehouses, commercial spaces, and historic properties and turning them into new housing; it's an especially apt topic as cities like Pittsburgh promote the widespread conversion of downtown commercial space into housing as a response to remote and hybrid work.

An increasing number of conversion ordinances and programs have propelled these projects forward. Los Angeles has seen a flourishing of newly created units, especially in its Arts District and Downtown, with more than 46,000 completed since the city's Adaptive Reuse Ordinance was passed in 1999. More recently, New York City announced a new effort in 2023 to rethink its zoning districts to allow for conversion of empty offices into as many as 20,000 housing units. By saving time and money — and building within existing neighborhoods containing transportation infrastructure — adaptive reuse can be a smart and sustainable way to help close the housing gap.

6. Embracing state preemption

NIMBY foes and allies in local government often push back against zoning reform, citing a variety of complaints about crowding, environmental issues, and neighborhood character. Increasingly, battles for housing regulations are being elevated to the state level. While there are examples like Texas pre-empting pro-housing regulations in cities like Austin, other states, most notably California, are pushing local governments to unlock housing creation and curtail restrictive regulations.

In recent years, California has established a suite of these measures: statewide rent control, requirements for new units, ADU laws, dismantling of single-family zoning, and bills to promote commercial-to-residential conversations and transit-oriented development. And the state has added teeth to this legislation by aggressively enforcing new and existing requirements.

Through zoning reform, planners can play an essential role in building affordable, equitable, sustainable communities, says Gray. In pursuit of equity and environmental goals in a changing city, thoughtful, evolving policies are essentials.

"I want to hit the reset button," he says, "and I think a lot of planners do, too. Lurking below the surface in planning is this eagerness, this appetite for a fundamental rethink."