July 31, 2025

Three miles. That's the distance that changed things. In the fall of 2019, I found myself running that distance comfortably without stopping for the first time after 58 years. With this came an unexpected shift in how I experience the communities I serve.

A routine checkup encouraged me to move more, so I began walking. Bored, I tried run-walking, setting a goal to trot a mile nonstop. That grew to two, then three. Early efforts were humbling, as I puffed my way through short, slow stretches.

Gradually, though, I improved. Then, after several months of effort, while I was on a quiet rural road, something shifted. My breath settled, my stride relaxed, and I felt fully alive. The countryside took on a fresh glow, stresses melted, and time appeared to stand still. What began as a chore became a joy — a new way to experience place, self, and life. I was hooked, and everything looked different after that run.

Now, after five years of running, I happily identify as a later-in-life runner, and in many ways feel like a transformed person. Among the benefits I've experienced are lowered stress levels, improved outlook, better sleep, and way more energy and focus. There has been literally no downside.

Beyond the physical and emotional benefits, running has provided an unexpected and invaluable lens for experiencing the places I serve as a city planning consultant. No Google Street View or site plan can replicate immersing yourself in a place at a runner's pace — its sidewalks and streets, gathering places, walkability, natural environment, neighborhoods, and all its strengths (and shortcomings).

Discovering places on the run

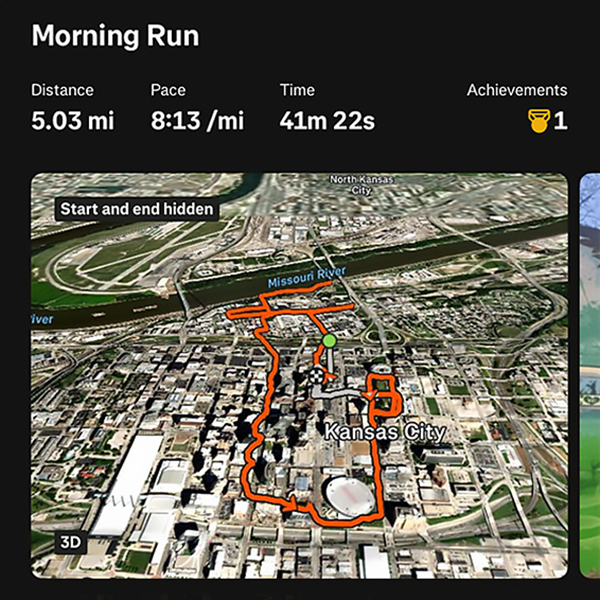

Running while on work assignments has become a necessity. As a founding partner in a small national planning firm, I'm often in hotels plotting an early morning run before meetings or work engagements. I check local routes on Strava or plot a course via the Maps app, looking for campuses, riverfront paths, and historic districts — places that promise to reveal a community's character. The route planning exercise itself is a means of getting to know a place better.

Sometimes, the routes are obvious or notable, but without real knowledge of conditions or unexpected interruptions, sometimes it is a challenge. In St. Louis, for instance, I headed out at sunrise for a riverside trail, only to be disappointed with a "Closed Due to Construction" barrier. Needing to make on-the-fly adjustments mid-run is a reminder that maps never tell the full story of a place.

One of Robert Barber's most memorable experiences was running in the Boston Marathon. Photo courtesy of Marathonfoto.

Barber tracks his near-daily habit, often logging more than 50 miles a week. Image courtesy of Robert Barber, FAICP.

Experiencing places this way makes those that prioritize and accommodate runners, pedestrians, and cyclists stand out. The vision of a place comes to life in the well-maintained sidewalk, a safe running path, clear wayfinding, and street trees — these elements reflect a community seeking to encourage and embrace human presence in the streetscape.

Maps and statistics fail to yield the rich and meaningful qualitative information absorbed while running. For example, running the Whirlpool Trail in Oxford, Mississippi, before sunrise reveals a quiet morning pierced with the sounds of dog barks and footfalls of fellow runners. Thoughtful connections to meaningful places (like William Faulkner's home, the Town Square, or the Ole Miss campus) and radiating byways create a desire to explore further.

In contrast, running through places inhospitable to pedestrians makes a safe run route a true challenge that calls for caution and a little bit of hope. No run is enjoyable while dodging cars, running along crumbling road shoulders, or navigating tricky crossings without signals or crosswalks. For me, these experiences lead invariably to planning questions: Why is there no walking route to this park? Why haven't these sidewalks been maintained? Where are the interesting destinations in this community and how do I get there?

On a recent run in one small southern city, the lack of sidewalks made moving on foot from the hotel district to downtown nearly impossible — and the downtown itself was clearly desperate for redevelopment. I could tell from the ways drivers reacted to me that early morning runners were a rarity.

Still, I was struck by the possibilities: How does the community perceive itself? Are these challenges recognized, and how can improvement and revitalization be sparked? How can a pedestrian system be established and the love of place be rekindled?

This is the very place where community transformation begins — in the mind, as a vision where hope is born.

Experiencing place through movement

This approach is nothing new to planning. Walk audits, neighborhood tours, and site visits are all staples in the planner's evaluative toolbox. But running offers a different kind of engagement. It allows for distance, time, and reflection. Transitions between neighborhoods, development patterns, evidence of street life, shade, public art, and — most importantly — people are all a part of the tapestry.

The most memorable runs deepen my appreciation of planning, its history, and placemaking —tracing the transition from small-town Mississippi to adjacent Choctaw Lands or navigating a wrong turn in Peru. Boston's iconic marathon route, the Lewis and Clark Trail in Great Falls, the Bay Mills community of the Chippewa, the cobbled streets of Antigua — they all have offered unmatched insights for which I'm grateful.

Barber looks for routes that prioritize and accommodate runners, such as a riverside trail in Great Falls, Montana. Photo by George Dodd/iStock/Getty Images Plus.

Reflecting on these experiences informs not only individual projects but also deepens understanding of city planning's very foundations. Robert Moses's severing of New York from its waterfront resonates loudly when I see a project cut off a neighborhood from its downtown.

Meanwhile, running in Central Park touches on the legacy of Frederick Law Olmsted, as a well-placed park or pedestrian-friendly street echoes the best of Garden City planning.

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs looms like a prophet with her thoughts about cities, streets, and people: "A city street equipped to handle strangers ... must have three main qualities: a clear demarcation between public and private space, 'eyes upon the street' from natural proprietors, and its continuous use to maintain vitality."

Planning on the run validates her profound insights, offering a firsthand experiential view of the thriving places that embrace these principles — and those that struggle because of ignoring them. Full understanding and appreciation of place occurs on a human scale and at a human pace. Planning on the run provides this in abundance.

What began for me as a step toward better health has become a pathway to deeper insight into both myself and the places I serve. Planning on the run has enhanced my personal well-being and renewed energy, focus, and joy in both life and my work as a planner. I've discovered that personal wellness and professional insight share the same road.