Nov. 17, 2025

Colorado made a bold housing move earlier this year: To encourage higher-density development and enhance the quality of life for apartment dwellers, the state enacted a law in May allowing multifamily buildings of up to five stories to be built with a single staircase instead of the two previously required for municipalities with populations exceeding 100,000.

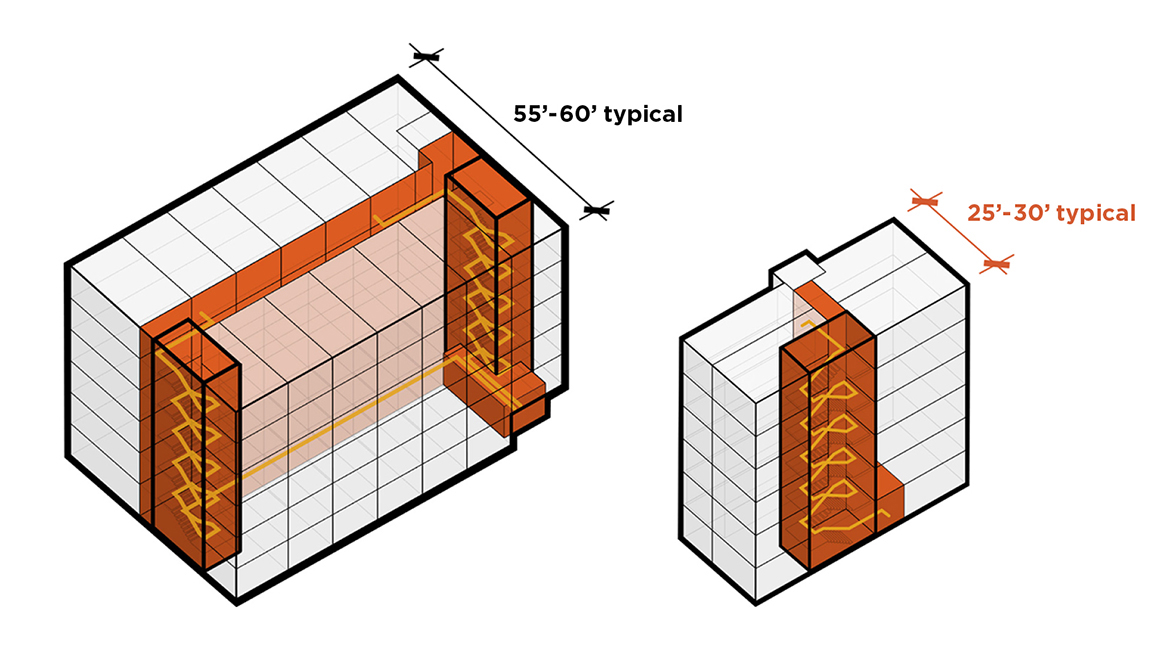

Requiring fewer staircases — sometimes referred to as "smart stair" reform — can lower construction costs by hundreds of thousands of dollars per building, says Stephen Smith, executive director of the Center for Building in North America. Updating building codes to permit just one staircase also can allow apartments to have windows on more than one side for better ventilation, more daylight, and greater comfort for residents, according to Colorado legislators, citing a 2024 George Mason University study.

However, building and zoning codes can sometimes be at odds because they are developed separately. "These codes need to work together," Smith says. "As planners seek to increase densities in cities, they are looking at small, single-family [-sized] lots, and a single stair is a tool in the toolkit."

Listening tour delivers results

It took pro-single staircase advocates in Colorado years to get municipal building officials, fire marshals, developers, and architects on board with the change, with many conversations about public safety concerns. After an earlier attempt to pass single-stair legislation failed in early 2024, state legislators — including Rep. Andrew Boesenecker of Fort Collins — began building support for another try. "We knew that we would need a long runway," Boesenecker says, "based on the conversations that had transpired with the previous bill that did not pass."

Outreach efforts included a listening tour with city officials, builders, and other stakeholders — such as the Fire Marshals Association of Colorado, the state chapter of the International Code Council, and the Associated Builders and Contractors Rocky Mountain Chapter — to address their concerns. The feedback resulted in nearly two dozen amendments to the 2025 legislation, including requirements for a staircase to be at least 48 inches wide, a maximum of four apartments per floor, and mandatory smoke detectors and alarms that meet National Fire Protection Association standards. Developers also must comply with International Building Code standards for sprinkler systems and construction materials.

The listening tour was something that Kate Conley, a principal at Architects FORA in Fort Collins, appreciated. "There was still a little bit of nervousness, especially from fire departments, about the change," Conley says, "but how successful and relatively safe it has been in the jurisdictions where it has been used gives me a lot of comfort. There is already data to back up the claims that these buildings are equally safe."

Overall, Boesenecker, who co-sponsored the 2025 legislation, is pleased with the result. "This work is about building [trusting] relationships among people who might have divergent viewpoints," he says. "To the extent that we are able to do that, compromise and collaboration are often the outcome."

A wave of single-stair reform

In 1860, a fatal tenement fire led to a two-staircase mandate in New York — and made the external metal fire escape a fixture nationwide for more than a century. Seattle challenged this norm in the 1970s when it legalized single-staircase buildings of up to six stories with modern fire-safety requirements like sprinklers and fire-resistant construction materials.

Now, a wave of reform has swept across the U.S. as a response to a growing housing crisis. New York and Honolulu added single-stair provisions decades ago, and Austin recently passed an ordinance in April 2025 to permit single-staircase construction for buildings of up to five stories. Meanwhile, officials in Memphis, Tennessee, hope a new state law enabling single stairways in multifamily buildings of up to six stories will increase housing options by reducing construction costs and enabling development on smaller lots.

Having data to support reform is key. A February 2025 study by the Center for Building in North America and the Pew Charitable Trusts found that single-staircase buildings equipped with sprinklers do not present higher fire safety risks than two-staircase construction. Between 2012 and 2024, the rate of fire deaths in modern single-stairway apartment buildings with four to six stories in New York City was similar to other residential buildings. "Single-stairway buildings as tall as six stories are at least as safe as other types of housing," wrote the authors, who included Smith. "Allowing the construction of such buildings could provide much-needed housing, including homes for people with modest incomes."

The report also found that it costs roughly $200,000 to construct a second staircase for a mid-rise apartment building.

In Denver, the Single-Stair Housing Challenge winners designed projects with single staircases, affordability, environmental impact, and fire safety systems in mind. Image courtesy of Buildner.

Ahead of schedule in Denver

Back in Colorado, the new state law requires cities with populations of 100,000 or more — like Denver, Fort Collins, and Colorado Springs — to update their building codes by December 2027. Eric Browning, Denver's chief building official, outlined the code updates in a public meeting in June, saying the city plans to ensure new buildings are constructed with non-combustible materials, such as concrete block, masonry, and steel, or fire-resistant Type IV heavy timber.

Denver planners expect the city will comply with the new state law a year or more "ahead of time, but it's still very much a work in progress," says Sarah Showalter, AICP, Denver's director of planning and policy. She says it's a bit early to estimate the specific effects on the housing supply and affordability, but the city has identified nearly 6,000 parcels that already are zoned to allow for these single-stair multifamily buildings.

While the new state law doesn't have a specific affordable housing component, officials see the code revisions as part of "a number of steps Denver is taking to provide a greater diversity of housing options, which our citywide plans call for, based on community input," Showalter says. "The department also is looking at zoning and other regulations to create more opportunities for [missing middle] housing options in residential neighborhoods through our Unlocking Housing Choices project, which is also currently in progress."

A proposed five-story, single-staircase development comprising 15 units in Denver's Globeville neighborhood has received preliminary planning department approval. The project includes 13 market-rate apartments and two units designated for residents earning no more than 60 percent of the area median income. Planning officials did note that the developer has not yet submitted a comprehensive site development plan for formal city review.

While missing middle housing has been largely left out of the picture because of zoning regulations that favor either single-family zones or high-rise apartments, Conley, the Fort Collins architect, has seen community development corporations and land trusts express interest in the new Colorado law as a pathway to affordable home ownership. "I could see a smart-stair building being just as attractive for an affordable homeownership project as for an affordable rental project," she says.