Oct. 28, 2025

Have you ever visited a city and asked locals about neighborhoods, dining, parks, and other places you should check out? And, in the next breath, did you hear, "but don't go" to this or that neighborhood?

Having called Chicago home for decades, Tonika Lewis Johnson is familiar with the "don't go" concept. She understands how it can affect the people who live in those neighborhoods and contribute to the housing affordability crisis.

Johnson coauthored Don't Go: Stories of Segregation and How to Disrupt It with University of Illinois Chicago professor Maria Krysan, PhD. The book directly confronts how the phrase "don't go there," based on prejudice and negative perceptions, might do as much at keeping racial and economic segregation alive today as zoning, redlining, urban renewal, corrupt real estate industry practices, and interstate highway construction did throughout much of the 20th century.

Picking narratives apart

Over the years, the "South Side" label has become coded to mean "segregated," "impoverished," or "crime-ridden," despite about a third of Chicago's population living there and representing nearly half of the city's land area. While the South Side faces some of these challenges, as many urban neighborhoods do, parts of the North Side have the same conditions — but those labels don't define the area in the minds of outsiders as they do the South Side.

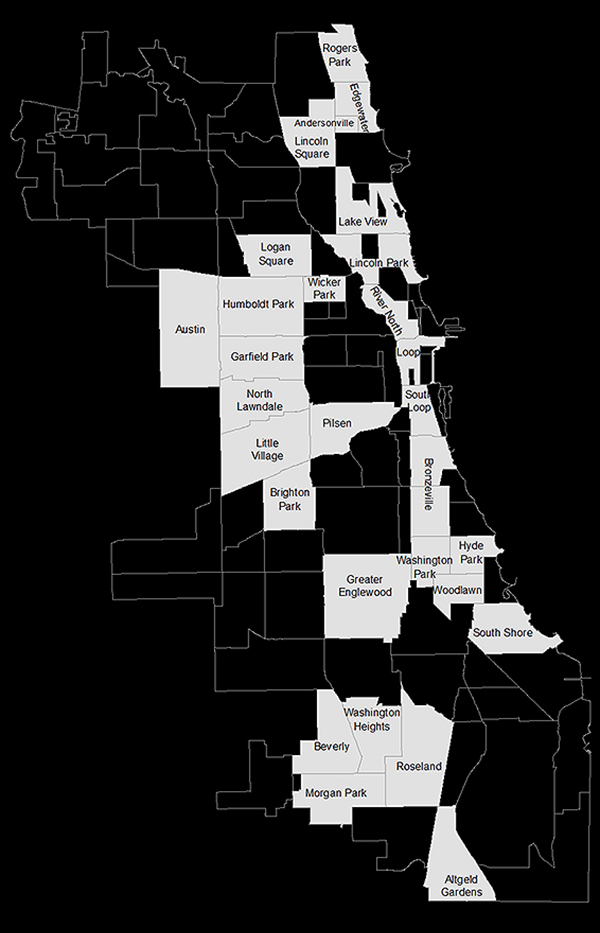

Key Chicago neighborhoods of those interviewed for Johnson and Maria Krysan's Don't Go: Stories of Segregation and How to Disrupt It. Image by Sarah Rothschild.

Johnson and Krysan focused on people's perceptions after they were told "don't go" to certain neighborhoods on the South Side. Photo by Colin Boyle.

This creates cognitive dissonance for Johnson, who grew up on the South Side and knows it is a far more complex place than the questions she would get about it. She lived in the Englewood neighborhood until she was seven years old and her family moved back when she was 11. But throughout her childhood, Johnson attended schools on the city's North Side — regularly crossing Chicago's rigid segregation boundaries and relating to people citywide.

Johnson, now a professional artist specializing in photography, has gravitated toward community activism. She co-founded the Englewood Arts Collective and the Resident Association of Greater Englewood. Her life experiences guided her to, as she says on her website, "reframe the narrative of South Side communities, and mobilize people and resources for positive change."

Johnson vividly remembers when she had the "don't go" epiphany. She and Krysan were presenting a Folded Map Project to a group of college students at Northwestern University. As she'd often done before, Johnson asked the students about their familiarity with the South Side. Her first question was, "How many of you have visited a neighborhood on the South Side?" A couple of hands rose. Then, she asked, "How many of you were told not to visit the South Side?" Nearly all the students raised their hands. Most weren't even from the Chicago area, but they'd heard about avoiding the South Side.

Immediately, Johnson focused on the message and its transmission. Media clearly played a part in this sentiment, but other players contributed to it, as well. "I asked that question many times, but when I asked them, it hit me a little different because of their age," Johnson says. "That led to me wanting to get people's stories about how that message is related to others."

This line of thought also appealed to Krysan.

Her sociology background meant she was experienced in conducting interviews, surveys, and focus groups, but getting people to talk about race was a challenge. "That's not that easy to do, so I've tried to bribe, cajole, sweet-talk, even pay people to get their responses," Krysan says. "But Tonika had a natural way of easing people into conversations on race and bringing out thoughts they'd often keep to themselves."

The Folded Map Project compares the same numbered addresses on the North and South Sides of Chicago, revealing completely different sociodemographic makeups. Video courtesy of Folded Map.

Part of that could come from Johnson's love for her home. To her, the South Side is a place of pride and accomplishment, full of working-class and middle-class communities alongside areas of wealth. It's full of hard-working people, fantastic institutions, great dining spots, recreation on Lake Michigan, and much more. However, she also sees the disparities between life on either side of the city and how the negative perceptions of the South Side have a tangible impact on the economic and social life there.

Johnson realized she could tell that story using the road naming-and-numbering system. Hundreds of streets cross the North and South Sides, divided by Madison Street. A major street like Ashland Avenue, for example, has street numbers that increase going north and south from Madison. By the time you reach, say, 5200 N. Ashland Ave. and 5200 S. Ashland Ave., you're talking about two points with strangely similar addresses that are more than 12 miles apart and have completely different sociodemographic makeup.

That's where Johnson started: finding these "folded map twins" and encouraging them to interact. What were their experiences, hopes, or fears? What would they talk about when they crossed the city's invisible divide? She documented the encounters in a photographic exhibit.

After that, Johnson and Krysan expanded on these experiences and their implications in Don't Go. They told stories of people like Adrianne Hawthorne, who grew up in Chicago's suburbs. After getting a car at age 17, Hawthorne decided to visit her grandmother, who lived in the middle-class South Side neighborhood of Beverly, but Hawthorne got off at the wrong exit and found herself in an unfamiliar part of the city. When she called her grandparents for directions, they got angry, telling her she was in a "very dangerous place."

Hawthorne remembers feeling a sense of shame in that moment, but she soon turned that into a call to action.

She started making a habit of taking the wrong exit and touring different neighborhoods. "I started to get off the highway at places I was told to never, ever go," Hawthorne says in the book. "It was not what I thought. It's just neighborhoods and nice homes. I was angry that I just blindly believed everything I was taught."

Adrianne Hawthorne, an artist and boutique owner in the Ravenswood neighborhood of Chicago, was inspired by Johnson's Instagram posts to visit new places, including her own grandma's "no-go zone." Photo by Tonika Lewis Johnson.

Planning implications

Some researchers are coming around to the idea that racial and economic segregation in the U.S. plays a significant role in the affordable housing crisis. Andre Perry, PhD, a senior fellow and director of the Center for Community Uplift at the Brookings Institution, has written extensively about this and the financial impact of having "don't go" neighborhoods in metropolitan areas. He's found that the "don't go" sentiment can easily become ingrained in housing markets, leading to devalued properties, particularly in Black-majority neighborhoods.

Perry and two coauthors examined home value data in 2018 and wrote that "10 percent of neighborhoods were majority Black, with 41 percent of the Black population living there, and 37 percent of the nation's U.S. Black population." They also found that in U.S. census tracts with Black majorities, homes were valued at roughly half the amounts of homes in census tracts with no Black residents.

Home and neighborhood quality did not fully explain the devaluation of homes in Black census tracts. Neighborhoods with similar amenities were valued 23 percent less in majority Black census tracts than those with fewer or no Black residents. In all Black majority census tracts in metropolitan areas, the research team found that owner-occupied homes were undervalued by about $48,000 per home on average — amounting to $156 billion in cumulative lost value.

Much of that lost value may be attributed to the "don't go" perspective. Certain neighborhoods end up with having lower value floors because fewer eyes are looking at homes for sale in them, even when those homes are comparable to other neighborhoods with higher values.

That's where the planning profession can come in. Planners recognize that there's value in all communities and can counter negative narratives through our work. We can advocate for the kinds of investments — in housing, infrastructure, commercial development, and improved public services — that make places better.

We can help the residents of so-called "don't go" neighborhoods by touting their assets while building on them.