April 1, 2021

"On your mark. Get set. Go!"

The children take off running, trailed by a parent trying in vain to keep pace. Their course on this winter day isn't a playground, but the middle of a wide thoroughfare: 34th Avenue in Jackson Heights, Queens. At 1.3 miles, it's one of New York City's longest continuous stretches of pavement pedestrianized in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. It's also at the heart of a neighborhood that has suffered one of the worst death rates in the five boroughs.

In the planning field, the pendulum has been slowly, fitfully swinging back toward a less auto-centric paradigm for the past several decades, propelled by concerns over climate change, safety, public health, and racial and economic justice. COVID-19 has only accelerated this movement.

Open streets and outdoor dining have served as high-profile responses to both the public health and economic crises — and not just in major metropolises, but in smaller cities and towns, too, like Midland, Michigan; Hendersonville, North Carolina; and Ballston Spa, New York.

Adding room for sustainable transportation has been another part of the response. Pop-up bus lanes aimed at speeding commutes and reducing crowding have appeared in Chicago and Boston, while cycling space was added in Denver and Philadelphia in response to a pandemic-induced biking boom.

These new car-free zones have seen varying degrees of success. Jim Burke, one of the founders of the 34th Ave. Open Streets Coalition, says it floundered at first in Jackson Heights. The city's initial Open Streets pilot, just a few blocks with cops and barricades at each corner, looked "like a police checkpoint... really uninviting," and was consequently barely used. Mayor Bill de Blasio declared the street and others like it too resource-intensive to operate.

That's when several neighbors came together to prove that an open street could work if it was designed to be welcoming. Donning orange vests and carrying sandwich boards declaring "Emergency Vehicles Only — Street Closed," the 34th Ave. Open Streets Coalition shut a block to traffic.

"The street filled with kids and adults," Burke says, "and we filmed it, and showed everyone, look, the world didn't end! Cars just made a turn. And look, no cops! No expensive infrastructure!'"

The DIY demonstration led to an expanded second iteration, plus an array of programming, including family bike rides; English lessons; salsa and Zumba classes; and collaborations with neighborhood artists, a parents' group at a local school, and the design nonprofit Street Lab. By October, when the pilot was slated to end, it had become a widely embraced part of the neighborhood. Hundreds rallied to support it being made permanent, which the city agreed to do just days later.

Now, a year into the pandemic, other designers, communities, and decision makers are assessing the feasibility of making these public space pop-ups more permanent. What are the current prospects for car-free and car-light zones? And how can planners help ensure those spaces are welcoming, well used, and advance justice and equity?

Rebalancing urban space

In planning for a more sustainable and equitable post-pandemic world, rebalancing urban space has taken center stage. It's a crucial component of the C40 Mayors Agenda for a Green and Just Recovery, released last July by a mayoral task force from the global coalition of 97 major cities working to address climate change. They've called for bolstering mass transit, "creating '15 minute cities' where all residents of the city are able to meet most of their needs within a short walk or bicycle ride from their homes," and giving streets "back to people" by "permanently reallocating more road space to walking and cycling."

Aimée Gauthier, chief knowledge officer at the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy, believes this moment can be used to recenter planning around well-being. She particularly emphasizes the need for transportation and land-use patterns that facilitate caregiving, which has significant implications for gender equity, given disparities in responsibilities for child- and elder-care, and the ability of older people to age in place.

"Transportation planning has been focused on the commuter, to the detriment, and almost to the exclusion, of other caretaking activities," she says, noting that commutes constitute less than 20 percent of all trips in the U.S. "It's left out: How do you get to the doctor? How do you get your kids to school? Do you have your activities close by?"

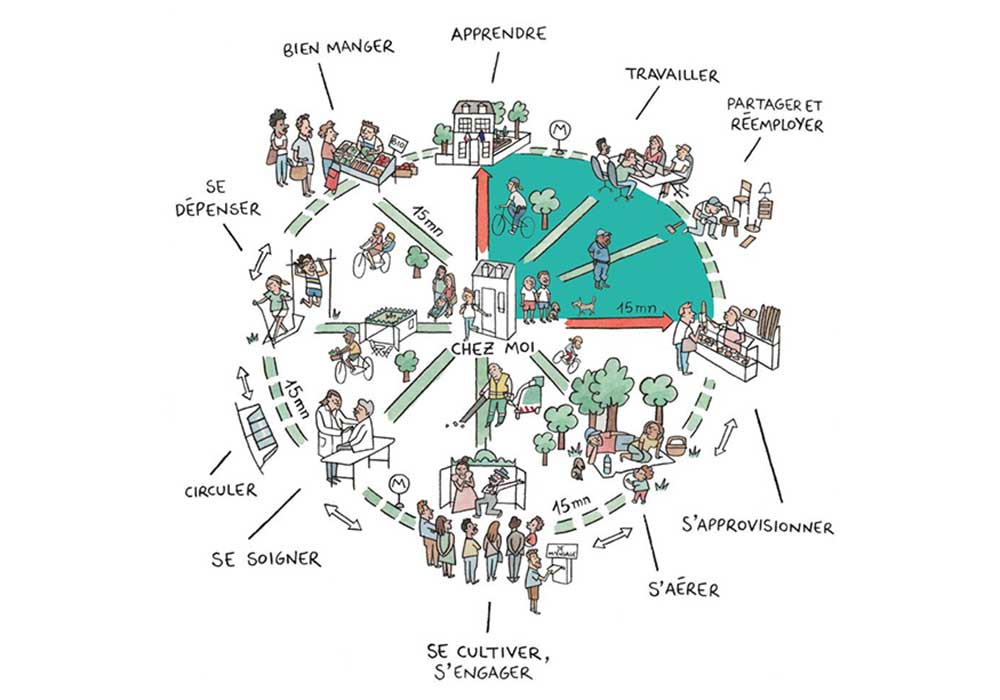

Paris Mayor Anne Hildago is reimagining the city with goal of making sure residents can be met within 15 minutes of their doorsteps. Image courtesy of Paris en Commun.

This perspective resonates to a degree with C40's "15-minute city," which gained global prominence last year as a plank of Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo's successful reelection campaign. Reapportioning space away from cars is core to the movement's objective of making destinations easily accessible on foot or by bike — but that, in some sense, is only the means. Safe, sustainable proximity to the elements of a full life is supposed to be the end goal. Hidalgo plans to pedestrianize major thoroughfares throughout the French capital (including the Champs-Élysées), make every street "cycle-friendly" by 2024, and turn 70,000 on-street parking spaces over for public uses, ranging from play areas to planters to public toilets.

But while buzzy, the concept has also been criticized for disregarding local contexts, community decision making, the threat of gentrification and displacement, and the spatial and social inequalities that structure US cities. "It doesn't take into account the histories of urban inequity, intentionally imposed by technocratic and colonial planning approaches, such as segregated neighborhoods, deep amenity inequity, and discriminatory policing of our public spaces," placemaker and urbanism theorist Jay Pitter, MES, observed at the CityLab 2021 conference earlier this year.

"Do you feel safe in public space? Are you welcome? Are you over-policed? Are you criminalized?" Gauthier says. "When you look at the intersection of your sexual identity, race, income, immigration status ... all of these things compound in public space and the public realm ... as planners, we have to be thinking about how to ensure communities are at the table and part of the planning process."

Ensuring accessibility is likewise crucial, a point starkly illustrated by the pandemic-induced boom in outdoor dining that, while taking space away from cars, has at the same time reduced access for people with disabilities. Planning for a wide range of mobility also makes spaces more inclusive for children, older adults, people pushing strollers or carrying groceries, and a variety of other users and contexts.

More than complete streets

What does the process of shifting to a less car-centric paradigm look like within a city?

According to Gauthier, facilitating a less car-dependent existence requires biking and walking infrastructure working in tandem with frequent, reliable transit, plus land uses that closely co-locate housing with commerce, services, and other key destinations. Safety, too, is a critical factor, fundamental to the equitable use of car-free zones and modes of travel.

Implementing those design features should start with listening, says Alysia Osborne, AICP, long range and strategic planning division manager of Charlotte, North Carolina. Charlotte Future 2040 — the city's first comprehensive plan since 1975, slated to go before the city council in June — is centered around the concept of "Complete Communities," which stipulates that all areas should be a short walk, bike, or transit trip to essentials and amenities, providing "safe and convenient choices for a variety of goods and services, jobs, and housing." Outdoing Paris Mayor Hidalgo's ambitions, North Carolina's largest city will aim for 10 minutes, not 15.

"It was a result of years of engagement around what people need," Osborne says. Her team has had more than 500,000 interactions with 6,500 people via in-person and virtual workshops and open houses, virtual scavenger hunts, socially distanced sidewalk chalking events, and Tik Tok challenges. The stories residents shared of long trips to work, schools, and grocery stores catalyzed the focus on equitable access.

That feedback added to the picture provided by one of the planning effort's first products, the Charlotte Equity Atlas. A spatial analysis of development, environmental conditions, and demographics, it found that neighborhoods extending from the east to the southwest of downtown, home to a disproportionate share of the city's residents of color and concentrated areas of poverty, had a less-complete built environment and reduced access to services, amenities, and employment, "a direct impact of redlining and the ongoing effects of explicitly racist and segregationist policies of the past."

Osborne says Charlotte 2040 focuses on universal connectivity as a means of addressing these disparities. "A quarter-mile or half-mile walk to a transit station is considered pedestrian-oriented, transit-oriented development. But that's just good development."

The question for planners there became, "How might we apply that same principle everywhere?" They answered with a holistic approach: The plan establishes 10 "Place Types" for Charlotte, which reflect both present uses and future aspirations, and will eventually guide neighborhood-level planning decisions. With mixed-use infill along commercial strips, hubs for transit and micromobility in manufacturing districts, active ground-floor uses oriented toward the street in neighborhood centers, and denser walking and biking connections across all typologies, they demonstrate how land use, building design, and mobility infrastructure can work in tandem to support a reduced reliance on cars in every corner of the city.

Getting to this vision will take ambition. The Charlotte MOVES Task Force, an aligned effort focused on mobility, called for $8 to $12 billion in total investment in a report released last year. Projects would include 90 miles of new rapid transit corridors, 140 miles of bus priority infrastructure, 75 miles of bike network investment, a county-spanning greenway system, and 150 square miles of first and last mile pedestrian infrastructure improvements. In a striking illustration of how patterns of development interact with transportation, the report says its proposals could cut vehicle miles traveled by anywhere from 13 percent to 40 percent, depending on whether supportive land use changes are enacted.

But Osborne says the city's increasing focus on the intersection of transportation, equity, and access is already yielding changes to the landscape. In October, the city council approved the city's first car-free residential complex; half of the 104 units will be affordable. It's just over a 15-minute walk to the nearest grocery store, and all residents will be guaranteed bike storage. She notes the proposed development is "less than a mile from the streetcar [expansion], really close to a greenway... [and] capital projects that will fill in the gaps in terms of sidewalk and bicycle networks."

It's a sign, she says, "of where we are as a community in shifting how we're thinking about mobility to how those other modes can serve our residents."