Environmental Justice Through Planning

Many factors result in communities that may be underserved, under-resourced, and overburdened by pollution. For this reason, a wide range of tools has been developed to promote environmental justice.

Although the law, public health, waste management, and public involvement have been central to the conversation about environmental justice in the U.S., it is necessary to acknowledge that environmental justice is also a community planning issue. In the U.S., some communities are facing environmental concerns that stem from a failure to plan or enforce proper zoning regulations.

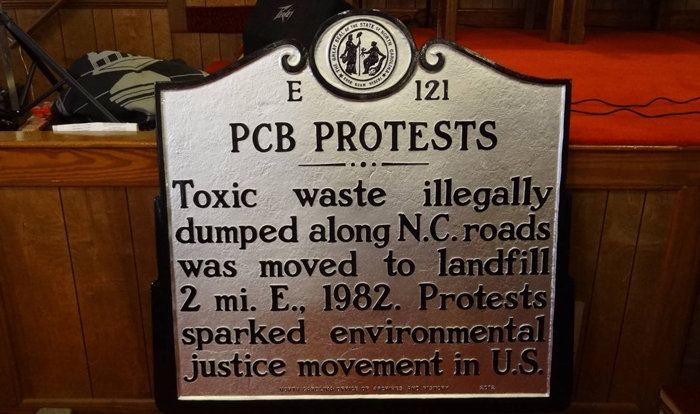

In 2012, the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources unveiled a marker in Warren County to acknowledge the birth of the environmental justice movement as an important milestone in the state's history. Photo by Carlton Eley.

Environmental Justice and Planning: A New Era of Collaboration

There should be no reluctance in making the connections between environmental justice and planning. The connections have always been present. When the environmental justice movement was in its infancy, citizens expressed concerns about being "overburdened by pollution." Some of the concerns included untenable practices in housing, land use, infrastructure, and sanitation. This is an important reminder that low-income and minority populations have always been concerned about the built environment.

Many planners have heard of environmental justice, but the challenge until now has been:

- framing how to implement it during the planning process

- visualizing the product from that process

- correcting the misperception that environmental justice slows down development

However, thanks to the tireless efforts of researchers and advocates, the creative thinking of planners and architects, and the compelling results of determined community builders, these barriers are coming down.

The 18th and Vine Jazz District in Kansas City was created in 1989. It's a trailblazer in place-based projects that balance the goals of economic development and cultural development. Photo by Carlton Eley.

Communities are finding ways to align environmental justice and planning as complementary quality-of-life goals, such as amortization ordinances in National City, California; comprehensive plan updates in King County, Washington; community-driven redevelopment in Spartanburg, South Carolina; and the like.

The narrative of environmental justice is a narrative about problem-solving. Long-standing problems. Some uncomfortable problems. However, these are not highly intractable problems because proponents for environmental justice and professionals who manage our built environment have a common interest. Through the practice of collaboration — not to be conflated with "conflict avoidance" — innovative, place-based solutions are being implemented.

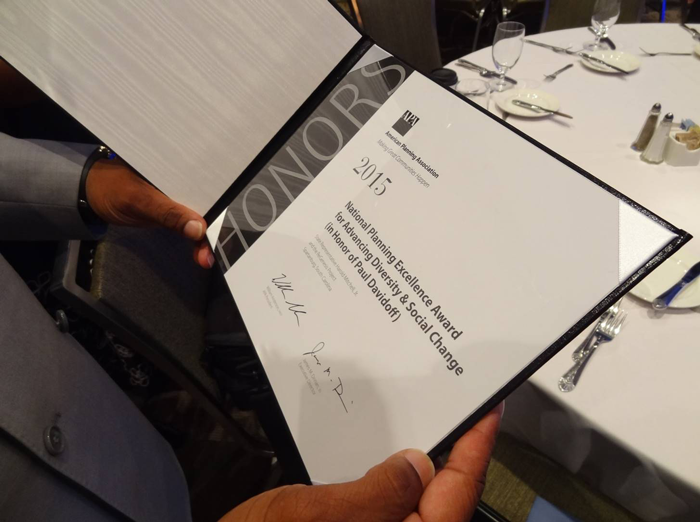

Although 32 years have elapsed since his passing, planners are still challenged and inspired by the legacy of Paul Davidoff. He viewed planning as a process to address a wide range of societal problems and to improve conditions for all people. He coined the term "advocacy planning," and his watchwords were "equity, social justice, and empowerment." Paul Davidoff was ahead of his time, and he died shortly before the groundswell of activity that resulted in what is now recognized as the environmental justice movement. Ironically, Davidoff's vision for "advocacy and pluralism in planning" is active in a place that few would look: the Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) Office of Environmental Justice.

Winner of APA's 2015 Paul Davidoff Award, the ReGenesis Project in Spartanburg, South Carolina, is a $300 million success story that easily reveals the nexus between environmental justice, land use, and sustainability. Photo by Carlton Eley.

Over 24 years, the office has developed many programs and tools for improving how agency staff work with citizens who live in impacted communities. Community involvement, community-based participatory research, the Collaborative Problem-Solving Model, Community Action for a Renewed Environment, and the like were created to fulfill EPA's mission. In retrospect, it is now evident that the lessons from these programs are transferable, especially for professionals who work in fields targeting the built environment.

The takeaway message is that environmental justice represents a strategy that professional planners can leverage, although it may not have been obvious in the past. In a nation of 319 million people, thinking critically about how to meet the needs of vulnerable populations properly is necessary to ensure everyone has a safe and healthy environment in which to live, work, and play.

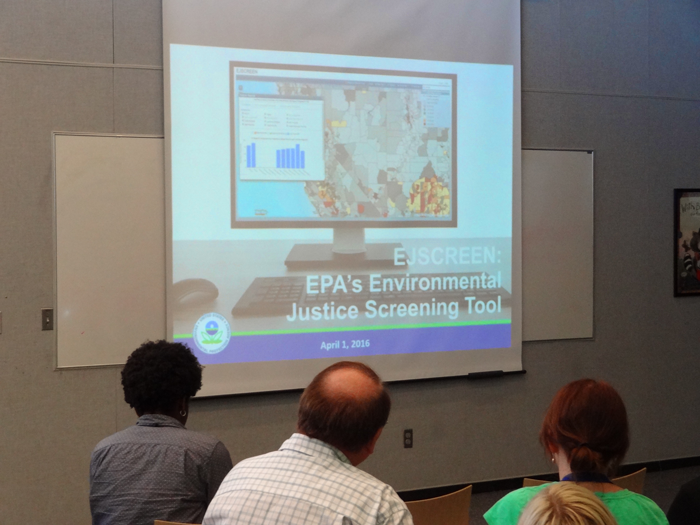

2016 National Planning Conference attendees in Phoenix participate in a demonstration of EPA's EJSCREEN. Photo by Carlton Eley.

Social Equity: A Planning Imperative

The practice of planning is not based on a static model. The profession regularly adapts to new trends, opportunities, and challenges. Events that have transpired in Ferguson, Baltimore, and Flint are tragic, and they are also teachable moments. They reveal the reality that planners will have to become proficient in addressing "social equity" issues that were seen as beyond their purview, including environmental justice. As a function of government, planning is swayed by politics. However, it is becoming increasingly apparent that the political act of "cherry-picking" is not solving difficult problems. Instead, it is simply shifting the burden of responsibility.

This course of action is neither responsible nor sustainable. It has micro-level implications that affect individuals and families as well as macro-level implications that affect the nation's ability to remain competitive globally.

The good news is this isn't a new conversation. Managing the social implications of land use and economic development decisions has been a recurring theme in planning practice, and professionals have 50 years of experience to draw from. Accessible answers and solutions are available for the intellectually curious, and only if we learn to rise above semantics. If it helps, think of environmental justice as a "proxy" for social equity and practice, advocacy planning, or equitable development.

Eric Shaw, Salt Lake City's director of community and economic development, addresses the National Environmental Justice Advisory Council during a 2014 meeting in Denver. Photo by Carlton Eley.

In closing, environmental justice is a forward-thinking, sustainable approach. It starts with community engagement and community clean-up, and it carries through to community recovery and redevelopment. In the end, the aim of encouraging environmental justice is intertwined with the goal of ethical planning practice. When implemented properly, both account for the social implications of policy decisions while extending quality-of-life benefits to everyone, especially vulnerable populations.

Top image: Facilitators discuss options during a technical assistance workshop convened by the Planning and the Black Community Division of the American Planning Association in Gary, Indiana. Photo by Carlton Eley.